Which side will you be on?…

Britain in the year 2020 is not a particularly easy place and time to live in. The highly emotive subject of Brexit has given motive to outright aggression and division between us all; in the media, in our families, amongst our media. Social media fosters intolerance and furious self-righteousness, opinions failing to disguise the sense of superiority they are delivered with, often without justification.

Since the Brexit vote, there has been a pronounced re-vocalisation of racism, leading to a concern of a rising and hostile nationalism. Developments in understanding and respecting other cultures (races, gender identities, etc.) are routinely dismissed as concerns of ‘snowflakes,’ ignoring that, outside of over-the-top ‘outrage culture,’ there is a more general attempt at play in trying to be decent to people.

Then there was the election of last December, which the media ridiculously and dangerously helped to reduce to a two-man, one-issue election where the Prime Minister, a proven racist, pro-privatiser of the NHS, and a political alienator, was elected in on the basis that he was less ‘dangerous’ than a man who, while not a strong, demonstrative leader, espoused policies designed to establish a fairer British society and decrease the gap between those with and those without. ‘Where would the money come from to pay for it all?’ people moaned, even though a lot of economists argued it was indeed feasible to run these policies if managed sensibly.

A two-man election.

Leave or remain.

An ever-widening gap between the wealthy and those who live in poverty.

Which side will you be on, indeed.

If… is a radical film made at a radical time in history, and it still speaks to us, now more than ever. Because as Britain embraces its own increasing turmoil, If… reflects this in allegorical terms, using a British institution as its centre, an institution to which we can trace back a lot of our failures of leadership: the British public school.

Charity Begins at Public School

Seemingly an oxymoron by name, the British public school really did begin as an institution for the development of the children of the larger public, namely the children of serfdom and the needy. Indeed, rather than paying feeder systems for the ruling elite, the schools were intended to be charities.

The original public schools were installed in the wake of Britain’s conversion to Christianity in the year 597. As new cathedrals were installed, a school would be attached to them, designed to take a small number of bright, needy pupils from the local community and instruct them in the ways of the clergy.

Later, after the Viking invasion, which saw the churches stripped of a lot of their assets, new schools opened that were intended to offer the brightest children of the poor a wider education than just clerical matters.

Again, these were charitable institutions, often run by rich landowners that had somehow made a success of themselves from humble beginnings, men such as William Wykeham, son of a farmer, who went on to become the Bishop of Winchester. With his insight into the poorer classes, Wykeham believed that with the right opportunity, the brightest of poor children could make something of themselves, just as he had. To such ends, his school did not charge fees to children whose parents earned less than £3,500 a year.

Sounds great, right? Enable the brightest to make the best of themselves, regardless of background or wealth, so that the country would have the best, most skilled people in the right positions for the running of the land.

So what went wrong?

Previously, education hadn’t been as much of a particular necessity for the sons of landowners, nobility, or royalty, earning their future titles and prosperity through birthright, loyalty, and connections. Learning was important, of course, but this could be done in-house, as it were. There was no need for the nobility, from their rarefied point of view, to mix with peasantry.

But the appeal of further elevation of status is irresistible to those for whom status is everything. As author and journalist Robert Verkaik put it, “the social advantage secured by entrusting a young heir to an institution that guaranteed a place at Oxford, even six centuries ago, was irresistible.” [1]

The problem was that these schools, being charities, were not intended for the sons of the wealthy. Not ones to let a little thing like charity get in the way, the nobility began to put pressure on the schools to accept their children, which they did, reluctantly at first but more enthusiastically as they saw their coffers fill up. Within a period of a few years, the number of paying scholars dramatically outnumbered those studying on free placements. And the paying students made sure that the free were very much aware of their station.

From here was born the ‘fagging’ system, a structure that helped to further establish the hierarchy within public schools of the wealthy and connected above the relatively poor. Older, senior boys would use the younger, often poorer ones as personal servants, engaging them in domestic chores such as brushing clothes, making breakfast and bringing tea. Ostensibly a reward for the seniors, it suggested that the seniors themselves would have experienced similar treatment in their early days at school and therefore would have experienced servitude from both sides of the coin. Whilst undoubtedly true to a point, the fact that the fagging system began as a way of putting the poorer pupils in public schools in their place, so to speak, reflects the attitudes these sons of the rich would have been exposed to in their own domestic dwellings. The fact that the fagging system also became associated with claims of sexual abuse puts a disturbing psychosexual spin on the power relationships between rich and poor.

According to the screenwriter Gavin Lambert, at the time If… was made “in the late ’60s, almost 70 percent of the British Establishment—politicians, generals, Church of England bishops, directors of major companies including the Bank of England—were products of the ‘strange sub-world’ of the public school.” [2]

Sadly, very little has changed in the 52 years since the film was released. Verkaik has posited that although only 7 percent of the general population attend a public school, that 7 percent represents “74 percent of senior judges, 71 percent of high-ranking officers in the armed forces, 67 percent of Oscar winners, 55 percent of permanent secretaries in Whitehall, 50 percent of Cabinet ministers and members of the House of Lords, and a third of Russell Group university vice-chancellors.” [3]

One only has to look at the Conservative government of the last 10 years and look at the names of some of the most dangerous and damaging members of the party during that time—current Prime Minister Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister David Cameron, Leader of the House of Commons Jacob Rees-Mogg, now-Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster Michael Gove and former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne—to see how far the reach of the public school is in terms of its insidious influence on our lives (interestingly, former Prime Minister Theresa May attended a state school, but unfortunately she was no less dangerous).

It is this, the insidious influence of the public school as a dangerous authoritative institution, that If… set out to address. That the film is still relevant says as much about the state of Britain as it does the brilliance of the film itself.

Crusaders

If… originally began life in 1960 under another name: Crusaders, a mock-epic title to match the grandness of the public school’s own lofty attitude to itself and the greatness of spirit of which a rebellion against such an institution must engender. That Crusaders sounds like something an adolescent with a classical, romantic attitude towards rebellion might have is apt on two counts; the film shows a trio of boys, the so-called ‘Crusaders,’ engaging in such an attitude, yet the initial script was also written under such circumstances, too. David Sherwin and John Howlett shared a painful adolescence in the confines of Tonbridge School in Kent, an experience Sherwin summarised as “nightly beatings and buggery. No mother. No father. A diet of cabbage and watery stew.” [4]

Sherwin and Howlett, both being devoted cineastes at the time, decided to get their experience down on paper and up on the silver screen. Crusaders was born, “an evil and perverted script,” in the words of Lord Brabourne [5]. But it would take another six years of threatened horsewhippings, the nervous breakdown of Nicholas Ray, and the last copy of the script left in a bus station waiting room before the script would end up in the hands of a certain Mr. Lindsay Anderson. Now Crusaders had found its director. But it would need to be transformed first.

Anderson was already a notorious figure in the worlds of cinema and theatre. Known for being a prickly, authoritarian director with a predilection for the surreal and anarchistic, he pressured and nagged Sherwin, now working alone (as Howlett wasn’t too enamoured with the direction the project was taking) to tighten the characters, make their relationships less fluid, make the script less sentimental and inject some humour into proceedings. Sherwin would be forgiven for thinking that Anderson didn’t like the script. But Anderson found himself responding to ‘something authentically adolescent and rebellious’ in the script [6]. He asked Sherwin to focus on the school itself rather than his own experiences; to consider the school “a strange sub-world, with its own peculiar laws, distortions, brutalities, loves, [and] its special relationship to a perhaps outdated conception of British society.” [7] As we shall see, in the way such a description reflects the public school’s relationship to the rest of Britain, it was very astute advice.

The majority of the filming took place at Aldenham public school, but Anderson was insistent the main exterior shooting took place at Cheltenham College, his former school, where he was head of house. To convince the college to allow this, Sherwin had to create a dummy script, one more in line with gentler school fare such as Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Needless to say, any references to buggery, authoritarian bullying and rebellious gunfights were not included in the dummy script. And it was when Sherwin asked for suggestions for a title for the dummy script that the ensemble landed on the title they would soon be using for the actual film.

So: why If…?

You’ll Be a Man, My Son!

Prodding around for ‘something very old-fashioned, corny and patriotic’ as a cover title for their public-school-friendly dummy script, Sherwin was reminded by a mutual acquaintance of Rudyard Kipling, now known as much for his pro-imperialist attitudes as for his writing [8].

In particular, Sherwin’s attention was drawn to one of Kipling’s most famous poems, ‘If’:

“If you can keep your head when all about you are losing theirs and blaming it on you… you’ll be a Man, my son!”

Sherwin was sold, but it was Anderson, as was now common in their working relationship, who turned the idea on its head and made it into something provocative. Seeing the title written on a board, Anderson added the ellipsis, injecting a note of ambiguity into the word. He then proceeded to decide that If… would make the better title for the real film than Crusaders.

Anderson recognised the irony in using the Kipling poem for his title. “You’ll be a man, my son.” And of course, the public schools, being all-boys establishments, were infested with narrow definitions of masculinity. To wield power, status, authority, assertiveness—that’s how you’ll be a man, my privileged son. Of course, the idea of being a ‘man,’ of living up to a social construct, is much more complex than such a two-dimensional model. Both Anderson and Sherwin would also have been well aware of how public schools perverted healthy sexual attraction between men, making homosexuality a further game in a power struggle rather than a natural expression of attraction and desire. Anderson himself struggled with his own homosexuality throughout his life, and whilst his public schooling is not the sole reason for this, the public-school perverting of his natural desires could not have helped him at all.

But the title of If… reflects the difficulties facing nonconformists as much as the narrow masculinity of the Establishment. Every rebellion faces the prospect of failure as much as success. As we know when we look back at English history, for every rebellion there is an authoritative response that dampers the embers of civil disobedience. Reforms, when they happen, are slow and hard-won. With this in mind, the title of If…, with its ambiguity-inducing ellipsis, raises the question of whether rebellion is even worthwhile—not in a moral way, but in an effective way. Is it right to rebel if the outcome is already pre-determined against you? ‘If only things could change. If only I could make them change.’ But what if you can’t make things change, no matter your method? Are you less of a man (or a woman)? If you can’t change the world, is it still right to try? All of this contained in one word, two simple letters and a row of three dots. Impressive.

What side does the film fall on? Establishment or rebel? To rebel or not to rebel? How do we answer the question contained within its title? Perhaps at this point it is easier to say the film is certainly not on the side of the establishment. But what faith has it in rebellion? “Emotionally the film is revolutionary,” stated Anderson, “but intellectually, I don’t know…the massed firepower of the establishment is ranged against (lead character) Mick.” [9] Clearly then, spirit was favoured over a rigorous critique and analysis when it came to the film. But how does it express this spirit, and how does this impact on its form?

A Formal Disruption

It’s clear that If… couldn’t pursue a social-realist agenda, the kitchen-sink dramas popular in the 1960s. The film’s clear emphasis on spirit over deep grassroots politics would not allow for as clear an expression of its ambiguous relationship to the possibility of change. A social-realist film requires just that: social realism. Not just its characters and world need to be authentic to how we know the world, but the form has to match this. It cannot be flashy or overly stylised, lest it take the viewer out of the world on the screen and therefore away from any messages the film might be trying to convey or even force upon the viewer.

For Anderson, the approach wouldn’t make sense for this particular film. “The problem of the script,” he said, “seemed to be to arrive at a poetic conclusion, from a naturalistic start (like any fairy-story or folk-tale).” [10] Torn between the epic and the fantastic, Anderson found a way to incorporate both, and in doing so found a form that transcended simple social propaganda and disrupted the viewer’s expectations of what a film about rebellion might look like.

The most famous disruption of form are the intermittent changes from colour to black-and-white scenes. There are various moments across the school, a roadside café, the chapel, where colour switches to black-and-white and back again, independent of the action being depicted. There is seemingly no rhyme and reason to when the changes occur, jolting the viewer by their random appearance and in doing so refocusing attention on what is on the screen, and allowing them to consider it in new ways or in extra detail. Anderson defined it as “an incitement to thought.”

Remarkably, these changes between colour and black-and-white were not initially designed to be included for any reason other than necessity. The film’s cinematographer, Miroslav Ondricek, advised Anderson that there would be difficulty in filming in the chapel, as the time they had been given to film there was short, and the time it would take to light the area sufficiently would cut too substantially into the time they had. Ondricek was shocked by Anderson’s solution; he told the baffled cinematographer to film the chapel scenes in black-and-white for speed, and he would perhaps film a few other scenes later in black-and-white also to cover the fact that they had to film in such a way to solve a problem.

What to Ondricek must have seemed like a careless, slipshod attitude to filmmaking resulted in the film’s most distinctive feature. Upon viewing the day’s rushes, Anderson was so impressed with how the black-and-white looked, particularly in conjunction with the colour scenes, that he decided to integrate the contrasting coloured scenes further into the film, as an aesthetic choice now rather than a technical necessity. In Anderson’s words, “The important thing to realise is that there is no symbolism involved in the choice of sequences filmed in black-and-white, nothing expressionist or schematic. Only such factors as intuition, pattern and convenience.” [11] Further scenes were filmed in this way, with the intention of audience disruption being at the forefront.

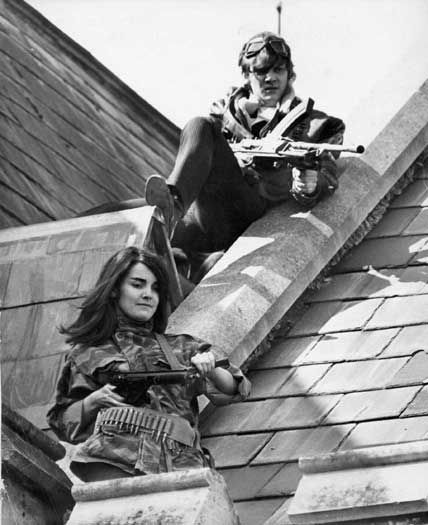

Whilst perhaps not as jarring as they were at the time of release, what with subsequent developments in cinematic technique, the transitions still pack a punch, and often if I haven’t the film for a long time, they will catch me by surprise still. The most effective transitions for me are where our protagonist, Mick Travis (Malcolm McDowell) and his friend Wallace (Richard Warwick) are engaged in a mock-heroic fencing match in black-and-white, the cut to colour occurring when the boys exit the hall and Mick, examining his wounded hand, cries in fascination “Hey! Real blood!” The second occurs at the end when the lecture from the pompous visiting General is interrupted by sudden smoke, and as the attendants evacuate the school, out into the suddenly sullen black-and-white of day (which could be read, however unintentionally, as being a comment on the drabness of everyday English life), Mick and his gang of crusaders open fire with guns they have found stashed away in the cellar of the school. It’s curious that the lecture was in colour and the rebellious attack in black-and-white, as the opposite way, with the rebellion in colour, would suggest that non-conformism would bring new vividness and colour into your life, metaphorically speaking. But the rebellion taking place in black-and-white only adds to the ambiguity of the film’s attitude as to whether rebellions can achieve what they set out to do.

The film itself rebels against convention, cinema convention, and by the end, it is not only the form but the action that comes to disrupt our senses as viewers.

As the film starts, it is reasonably realistic, showing the life of returning pupils to the school. But as we progress through the term, things start to get a little strange. Mick and his friend Johnny take an unexplained trip to town, where they steal a motorbike and arrive at a roadside café, where Mick tries to kiss the young waitress. The waitress replies with a slap, dampening Mick’s ardour. But then her mood changes, and what unfolds before our eyes is a mating ritual, the two turned into tigers, roaring and swiping at each other in legitimately animalistic passions until a sudden cut shows the two naked on the floor making love. And then we cut again to the girl and Johnny, sitting fully dressed at a table, while Mick sits down next to them spent. As a metaphor for wild, unbridled desire and lust as experienced in youth, it is most powerful indeed. Does it disrupt the reality of the film? Yes. And things only continue to get stranger.

The housemaster’s wife strolls through the boy’s empty dormitory naked. Mick, Johnny and Wallace are asked to apologise to the school chaplain for a misdemeanour, and a draw in a cabinet is pulled out, only to reveal the chaplain concealed in it. When the crusaders are punished by being charged with clearing out the school cellar, they find a foetus in a jar. Not only that, but they find guns. The firing of these guns from the roof at the assembled masses of parents and authority figures below, killing the headmaster in the process, is the icing on an already surreal cake.

Is the film fantasy? Some sort of dream wish fulfilment for the frustrated crusaders, repressed by their stay at school? A little bit of both, maybe. Ultimately, perhaps it doesn’t matter. Anderson described it as being that “in If…reality is negotiable. It coexists with fantasy, and there’s no dividing line.” Perhaps the film contains waking dreams which force themselves without warning into the world of the film, forcing us to untangle what is reality and what is not. In spirit, this non-conformism to standard cinematic rules represents Anderson’s attitude to the establishment and why the film is still relevant today: it is an affront to individualism.

Romance and Rebellion

While the spur for the film for David Sherwin was his experience in public school, for Lindsay Anderson there was always a bigger issue at play. In fact, Anderson is reported to have enjoyed his school days, having being a head prefect at Cheltenham, and was often caught on set reminiscing about the good old days.

So, what was Anderson’s attitude to the Establishment? Did it follow that if he was accepting of the public school, then he was accepting of authority in and of itself? Not quite.

“If you want a continuity of theme,” Anderson explained regarding his own works, “I think this is one: a mistrust of institutions and an anarchistic belief in the importance of the individual to make his or her decisions about life—rather than simply to accept tradition and the institutional philosophy.” [12] For Anderson, it was not simply the public school in and of itself that was the problem, but the public school as an institution, with a narrow and repressive, unquestioning attitude to its philosophy of status and masculinity. Tradition is only worth as much as its relevance to the contemporary world. If it is no longer relevant, then why persist with it? Because it is tradition? Anderson saw through this charade, and I wonder what he would have made of Brexit, with its suggestions and snide innuendos of being able to return to a supposedly more idyllic and happier Britain, one which only exists in the minds of the Establishment and those voters with selective memories who are frightened to admit they are frightened of a changing world, a world they no longer understand.

Why does this myth of a previously happy, more idyllic Britain persist? For the Establishment, there is a clear answer: that selling a disgruntled public on a return to a happier time, however suggested or assumed, will more than likely result in votes and keep that particular party in power.

But it is more than that. From the time they enter the school, this strange sub-world as Anderson put it, with its own codes, laws, rituals and language, the public schoolboys are separated from the ‘real’ everyday world of the general public, the mass they will soon come to rule. Because their experience is one of pampering, privilege and power, they cannot relate to someone who was bullied at school, whose parents had to scrimp and save to pay the bills, who used to play 10-a-side in the park with kids from the next street with jumpers for goalposts, who even had to use food banks just to eat. As Robert Verkaik argues, “Children who are educated away from the children next door can never integrate properly…so when they leave their protected ‘green zones’ and re-join the world community they are bristling with unconscious prejudice.” [13]

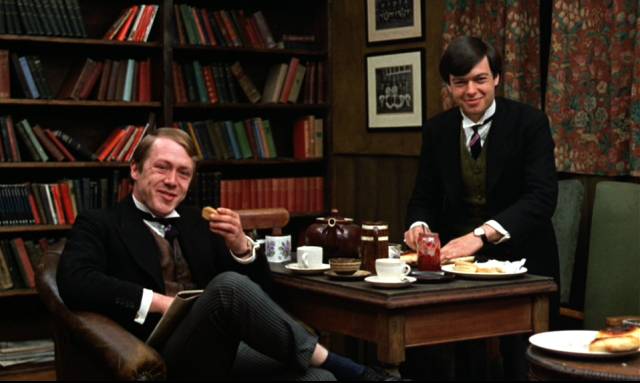

This lack of empathy and understanding from the privileged for the vulnerable or different is played out in If… strikingly. A new boy is berated waspishly by his new peers when he can’t remember the language and nicknames used to describe the school and its masters. This same boy is later hung by a gang of cackling peers from a toilet cistern, his hair dunked in the toilet water, and is left to marinate, as it were. Disturbingly, the boy who eventually lets him down is more disappointed in the victim than in his attackers. The Whips discuss their younger servants in the fagging system with disdain, chastising Bobby Phillips for bringing a substitute breakfast muffin when the original item of a crumpet is not available. “It’s not up to you to think,” Bobby is told coldly. Do as I say, not as I do.

But this is not the only unsavoury aspect of the fagging system on display here. The Whips discuss their servants in reductive, lusty, objectifying ways. “He gets a little lovelier each day. Lazy little bugger,” says one about someone under their charge. The abuse of power at the basest level is clear. But the abuse goes deeper. The Establishment bullies itself. Sensing that one of his Whips, Denson, is uncomfortable with this blasé discussion of the sexualising of their servants, possibly afraid of exposing a vulnerability regarding his sexuality, the head Whip Rowntree assigns Bobby Phillips, the servant under discussion, to Denson, knowing that this forcing of Denson’s object of desire on to him will cause him undue anxiety and self-examination, even if sexual consummation will make him happy on some level in the end. Rowntree is clearly amused by this. We can assume he enjoys the idea of his friend’s discomfort and escalating it further. You only have to look how MPs in the House of Commons, grown adults trading playground insults over the issues that affect our lives, or the way Michael Gove turned on David Cameron during the build-up to the Brexit vote, to understand how something like this passive-aggressive move of Rowntree’s to Denson could play itself out in such a way in their professional, adult lives.

But it is the tension between Mick and his crusaders and the Whips that really highlights the difference between the Establishment and those outside it. Mick is an intelligent young man. He is also a romantic, hemmed in by the world around him that does not tolerate such romanticism. If romanticism can fairly be linked to the arts and with creativity, then the Establishment’s attitude to romanticism can be discerned from the cuts to arts funding under the Conservative government.

Because the Establishment trades in surface levels, easily identified tropes, and a further narrowing of understanding and empathy, any behaviour, including such things as movement, dress, and slang, can be given an anti-establishment ideological meaning that is not really there. It doesn’t conform to a narrow understanding of what is the ‘proper’ way to be. When Mick returns to school from the holidays with a moustache, it’s clear he grew it because he saw it as an adventure, an adolescent trying on a pose, a play at adulthood. But from the establishment’s point of view, clean-shaven faces are the correct way of presenting oneself. This is why Mick sneaks in with his face covered and shaves at the last possible moment. He knows his gesture would not only be not tolerated, but would be given a meaning that is not really there.

Likewise, in their little hidden common room, the crusaders have a collage pinned to the wall of various rebels, freedom fighters. There does not seem to be one particular form of politics or cause represented in these images. Again, it is style over substance, the romance of rebellion, like modern-day students who put posters of Che Guevara on their walls as a rebellious symbol, only for them to crumble when you ask them to detail anything specific about his politics or history. A Rage Against The Machine album does not a rebel make. And yet this does not invalidate the spirit, the youthful vitality of the feeling. “When do we begin to live, that’s what I want to know,” bemoans Mick, echoing every frustrated teenager awakening to the bias and unevenness of the adult world.

The existentialist language on display, the fatalism, indicates someone who has a well-thumbed copy of Camus’ The Outsider (aka The Stranger) or Goethe’s Young Werther in their coat pocket. Anderson essentially confirmed this when he said, “Mick plays a little at being an intellectual (‘Violence and revolution are the only pure acts,’ etc.)” [14] Yet, when Mick describes the proper way to treat a beautiful girl (“There’s only one thing you can do with a girl like this. Walk naked into the sea together as the sun sets…make love once…then die”), Johnny’s excited reaction of “Fantastic!” is the giveaway. Rather than despair at the inevitability of suicide, he seems excited about the prospect, equating sex and death into a kind of romantic, emotional ideal for living. Anyone who has been through a teenage existentialist phase (me included) will understand the exciting melancholy of such a sentiment.

The language used about the crusaders by the Whips, however, particularly the moody, repressed Denson, oozes disdain and scorn. Shamefully, we are currently being led by a Prime Minister, a former public schoolboy, who has a history of making racist and homophobic remarks. The language he used to make these remarks typically objectified the subject of the remarks in question. Here we can see The Whips objectifying the crusaders in the same disgusted tones, as bohemians, dreamers, romantics. When Denson calls Mick “a degenerate,” it is both unnecessary and cruel. However, it is also revealing of the underlying bias that lies beneath the language. It basically boils down to an attitude of “us and them,” under which our country has been governed for a long time. Discussing Mick, Anderson comments that “when he acts it is instinctively, because of his outraged dignity, his frustrated passion, his vital energy, his sense of fair play if you like. If his story can be said to be ‘about’ anything, it is about freedom.” [15]

Freedom, however, is not on the agenda for the Whips and their intervention to deal with the crusaders. At this point, the crusaders have not done anything particularly severe or deserving of hard-line punishment. This matters not a jot to the Whips, who judge based on attitude and difference first. Their upbringing has given them a disproportionate sense of power and authority. This, in turn, is reflected out disproportionately onto people who are judged and contained underneath such authority. As Rowntree states to the housemaster, wavering uncertainly under the certain, steely gaze of the Whips, “I will have to deal firmly with it in certain instances. It may be necessary to make a few examples. The headmaster doesn’t like too much thrashing. He wouldn’t like college to get a reputation for decadence.”

And what an example to give. Do as I say, not as I do. Rowntree lays down the law to the crusaders in unempathetic, unambiguous terms: “I imagine you know why you’re here…for being a nuisance. A general nuisance in the house… It’s your general attitude. You know exactly what I mean. And we’ve decided to beat you for it. Stand up properly when the head of house addresses you. There’s something indecent about you, Travis. The way you slouch about. You think we don’t notice you with your hands in your pockets. The way you just sit there looking at everyone. You three have become a danger to the morale of the whole house. You can take that cheap little grin off your mouth! I serve the nation. You haven’t the slightest idea what it means, have you? To you it’s just one bloody joke… You’re in the sixth form now. You should be prepared to set an example of responsibility… You’re a nuisance. You’re pathetic. And as such, you must be punished.”

Slouching and hands in pockets are not the most threatening things to society, yet the Whips are prepared to beat the crusaders for it and what they feel it stands for. So imagine their astonished, insulted fury when Mick responds to Rowntree thus: “The thing I hate about you, Rowntree…is the way you give Coca-Cola to your scum…and your best teddy bear to Oxfam… and expect us to lick your frigid fingers… for the rest of your frigid life.” It is a beautiful, insinuating comeback which clarifies exactly what is at play—a power struggle. And it earns Mick a ferociously brutal bit of retribution.

He who wields the cane, it seems, wields the power, and the quiet dignity in which Mick as the ringleader takes his punishment, arms spread across a gymnastic bar as if being crucified, is sobering. Violence and bullying is a well-known common dominator in many public schools throughout history, and in fact the cane was only banned in state schools in 1986, its relative closeness in years all the more shocking. I was born in 1985, and never have I been more grateful. Beaten children become bitter children become defeated adults. What does the Establishment care? It is at a distance removed, after all.

A distance removed from decency, too. As Mick goes to stand up after he has taken the six strokes given to his comrades, he is shouted at to bend back over. As the ringleader, he must have an example made of him. The deck is obviously stacked, and the rules manipulated on the fly. The pure disgust on Rowntree’s face as he lays a further six smacks of the cane down onto Mick’s lower back is awful, appalling. When Mick stands back up, which he struggles to do, his body in pieces, he maintains his composure and his dignity as much as he can. The tears rolling down his face, though, tell a story of pain, anger, terror, and shame.

Here is an abuse of power. And while, since the awful police brutality of the 1970s and 1980s is behind us, with the police afraid to act too forcefully for risk of public scorn in the media, the establishment enforces power in other ways using its own stacked deck, often using finances to hit down at the lower classes. Bedroom taxes, for example—the nerve of these people, owning houses with more than two bedrooms! Closing resources like Sure Start centres and libraries, things that act as community hubs, so that people can’t get support or access to resources anymore. These acts are as much an abuse of power and acts of violence in their way as a caning.

That this should result in rebellion, gunshots, and spilt blood, fantasy or not, is not surprising. You can only back an ‘animal’ into a corner for so long before it lashes out to defend itself. And sure enough, looking back over British history, there have been many riots. All eventually are squashed by the establishment. Because the establishment holds all the might, all the keys to the kingdom. If Brexit is unsuccessful, if Britain falls into a worse state because of it, what then? Will people take to the street once more with weapons and petrol bombs and incoherent rage? Will they win? History says otherwise. Should they still try, then?

Let me give the final word to Mick himself, Malcolm McDowell:

There is a lot of Travis in me…I wouldn’t have the guts to get up there and shoot all those lovely people, but after the film I took a holiday in Cannes and looked around me at all the lovely people on the beach and imagined myself with that machine gun and the bullets flying. They were all there with their yachts and expensive cars, while the peasants in the field were hardly scraping a living. [16]

I don’t condone violence, but there is the conflict, boiled down to its simplest terms. If… is more relevant than ever.

[1] Verkaik, Robert. Posh Boys: How the English Public Schools Ruin Britain. London: Oneworld Publications, 2019.

[2] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[3] Verkaik, Robert. Posh Boys: How the English Public Schools Ruin Britain. London: Oneworld Publications, 2019.

[4] Catterall, Ali & Wells, Simon. Your Face Here: British Cult Films Since The Sixties. London: Fourth Estate, 2001.

[5] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[7] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[8] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[9] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[10] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[11] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[12] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[13] Verkaik, Robert. Posh Boys: How the English Public Schools Ruin Britain. London: Oneworld Publications, 2019.

[14] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[15] Lambert, Gavin. Mainly About Lindsay Anderson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2000.

[16] Catterall, Ali & Wells, Simon. Your Face Here: British Cult Films Since The Sixties. London: Fourth Estate, 2001.

All background information is taken from the above-referenced sources unless otherwise stated.