If you haven’t seen Black Mirror, well, I’m not sure why you’re here. If you have, you know it is arguably one of the most important and thought provoking shows of our era. TV Obsessive is proud to feature analyses of each and every episode. Here, Caemeron Crain digs into Black Mirror S1E2, “Fifteen Million Merits.”

The spectacle manifests itself as an enormous positivity, out of reach and beyond dispute. All it says is: “Everything that appears is good; whatever is good will appear.” The attitude it demands in principle is the same passive acceptance that it has already secured by means of its seeming incontrovertibility, and indeed by its monopolization of the realm of appearances. – Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (1967)

Black Mirror “Fifteen Million Merits” does something great sci-fi tends to do: it throws one into its world and begins to explore it without a lot of exposition as to what exactly is going on. We have to figure that out ourselves.

That being said, the world presented herein is not terribly complex (though there are some questions as to its broader aspects I will touch upon later). Individuals in drab grey sweats pedal stationary bicycles, and do other things, to earn “merits.” They are bombarded with entertainments, have to spend merits on things like toothpaste and food, and are subjected to ads they cannot escape.

We get most of this through our protagonist, Bing, who does escape some of those ads by paying some merits, but whom we also see chastised for closing his eyes during one that he has not skipped. (It is not clear exactly how the system knows he has closed his eyes—we are left to speculate as to what unexplained tech may be involved.) All of the walls of his room are screens he cannot turn off. He is even hit with a personalized ad while in the bathroom, at a particularly inopportune moment.

There may be other entertainments on offer, but three stand out: Hot Shot, which amounts to something like American Idol; Wraith Babes, which is basically porn; and Botherguts, a show that seems to involve shaming the overweight in way that never quite makes sense. In short, it is all very shallow. One could imagine a channel featuring cute pictures of animals being thrown right into this mix, though that would perhaps not hit the same note in terms of the spirit of the episode.

With that setup in place, the plot of “Fifteen Million Merits” is straightforward: our friend Bing hears a newcomer named Abi sing in the toilet and develops a crush on her (in whatever order); he proceeds to praise her singing to her, and offers to gift her a ticket to audition for Hot Shot. She demurs, of course, but he insists, saying that he just wants something real to happen for once.

Once she arrives on stage, to sing Irma Thomas’ “Anyone Who Knows What Love Is,” Judge Wraith says he wants to see her titties first. And though the other judges push back and allow her to sing, they agree afterwards that she is better suited to Wraith Babes erotica than anything else. She hesitates, they insist it is better than the bike, the crowd of dopples chants, “Do it!” and she finely acquiesces. Bing starts to throw a fit and is removed. Along the way, Judge Wraith tells her not to worry about shame, because they medicate for that.

This is one of a number of things mentioned in the episode that can lead the mind to wonder. Mostly directly, Abi is forced to drink something called “Cuppliance” from what amounts to a juice box, prior to going on stage. What is this, and what does it do? What role does it play in her ultimately going along? It would seem less than a definitive one, since she pushes back, and hesitates, nonetheless.

Judge Wraith’s remark gets to a deeper question, though: is shame something to be medicated against?

It is certainly not a pleasant emotion, as anyone who has ever lain in bed at night contemplating past mistakes can tell you. It is also distinct, though, from guilt, insofar as it is less about what one has done than who one is.

So, here’s question 1) Is shame a useful sentiment? (Is guilt?)

And 1a) Is medicating against shame objectionable? Why or why not? We already medicate against depression, anxiety, and so on. To be clear, those medications help a lot of a people, and we should work against the stigmatization of mental illness, but should we not perhaps also ask whether it is a societal problem, rather than an individual one, if great numbers are dealing with these issues? And, again, then, what about shame? A quick line in the episode points to a deeper question as to the appropriate limits of psychotropic medication.

Abi’s choice of song also hits an ironic note, insofar as it is doubtful that anyone in the world of “Fifteen Million Merits” knows what love is. This is a world of surface, simulacrum, and spectacle. We are shown individuals who are smitten, but nothing close to romance, much less love in a deeper sense. Everything has been commodified, and, in the end Abi agrees to become a commodity herself. When we see her later on Bing’s screen she seems precisely to be a ghost of her former self, or, rather, a wraith.

This could be the end of the story: Bing gets a crush on Abi and gifts her the merits to try out to be a pop star, but she ends up being a porn star, and he is wrecked over it. But, that isn’t the end of this story. As much as we may empathize with Bing when he can’t turn off the ad for Abi’s porn—because he gifted her all of the merits that would have enabled him to do so—he is actually closer to the villain of this story than anything. After all, he pushed her into that situation. She seemed happy to live hand to mouth. (And what does the Cuppliance do!?)

Perhaps one should be more sympathetic to Bing, and, ‘villain’ is probably too strong a term, but it would seem that he was acting on nothing more than a fairly juvenile crush. When he says he wants to see something real for once, he seems to be thinking that her winning on Hot Shot would be, but then her becoming a Wraith Babe isn’t? What is the difference? Is it not merely a difference as to what kind of commodity she would become, in this world saturated by commodity fetishism?

2) Are all of our reality TV shows, memes, cat videos, and so on, just differing forms of pornography? (What defines pornography, as a concept?)

Abi becomes a wraith (babe)—a ghost-like image of herself—but doesn’t that more or less go for everyone in this world, with their dopples, and so on? The audience of Hot Shot is a simulacrum of an audience, composed of images representing individuals rather than the individuals themselves. Each is actually watching alone in their room. This separation, or alienation, lies at the heart of what Guy Debord labeled the “society of the spectacle.” How much difference is there between this and the world we live in? It is as though lived experience is not real until it is represented—posted to social media, and thus inscribed in a space of images we each partake in separately from one another.

Bing ultimately rebels against this by punching at the screens in his room. He can no longer afford to skip things, because of his gift to Abi, which means that he cannot skip the ad for Wraith Babes featuring her. So, he throws a tantrum. He bashes the walls of his room, breaking the glass thereof, and then discovers a shard that could be used as a weapon.

One might expect that he would be punished for this, but we are not even shown the clean up process. Abi gets her origami penguin taken away because it is detritus, but Bing manages to hide not only that, but an empty Cuppliance box and glass shard, under his mattress. This seems like an inconsistency in the universe being presented, but it is perhaps best not to get too caught up on it. We are not shown the full world, after all, and are given very little information about those who are tasked with cleaning up (other than that this can be a demotion from riding the bike)—what are the lives of these people like?

Bing dedicates himself to earning another fifteen million merits, and ultimately his plan becomes clear. He goes to audition for Hot Shot, with the shard of glass and Abi’s empty Cuppliance box hidden in his waistband. He uses the latter to avoid drinking the substance before he goes on stage himself. When given his chance, he dances a bit, before pulling out the shard of glass and placing it against his throat. He threatens to kill himself unless they hear him out. While Judge Wraith suggests he just go ahead with the suicide and get it over with, the other Judges want to hear what he has to say.

Bing proceeds to rant against the society we have been shown throughout the episode: the bullshit labor of riding the bike (what are they powering, if anything, besides the entertainments they are bombarded with?), the “fake fodder” they strive to earn (upgrades to a dopple, e.g., that is not even real), and the exploitation he now sees as being carried out largely by these Judges themselves. “F*ck you for me, for us, for everyone!”

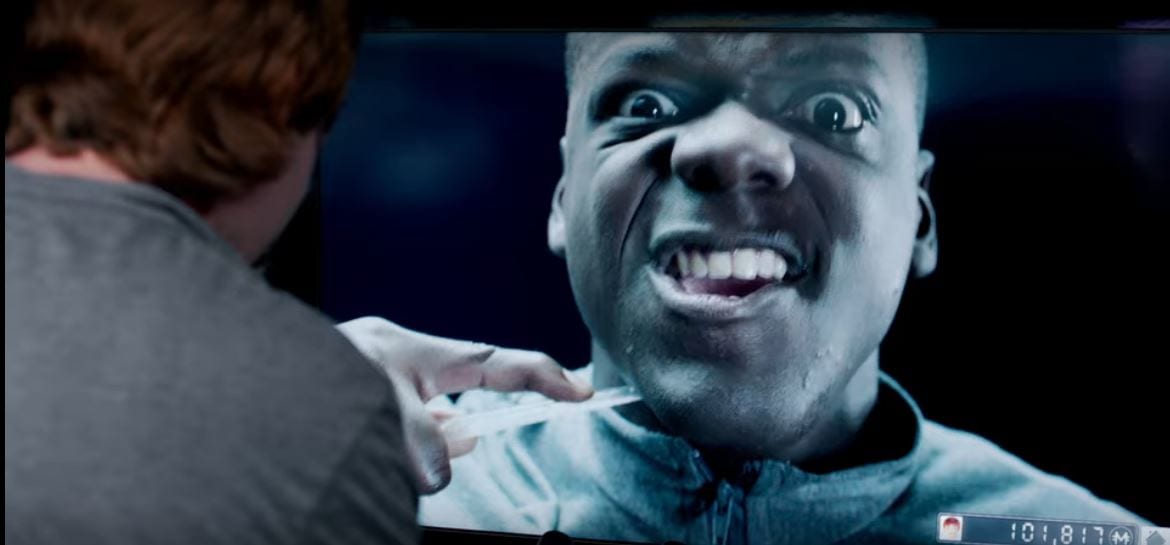

After a brief silence, Judge Hope begins to speak in the style we have seen previously, both in this episode of Black Mirror, and on competition shows like this in the real world. “That was without a doubt…the most heartfelt thing I have seen on this stage since Hot Shot began!” He claims that Bing has captured something they all feel—that authenticity is in short supply—and proceeds to offer him a show. And when Bing accepts, there is no Cuppliance to be blamed.

The attempt to rage against the system is taken up and commodified by the system itself. Bing’s show is a success. One can now purchase a Bing shard for one’s dopple. He holds the original to his throat as he rants on the screen, and places it in a special box after he finishes. There is no escape; no real outside to this society of the spectacle. Resistance has become one of its moments; another commodity to be consumed if one desires.

3) Is it possible to be authentic anymore? Can one rebel against this system of commodification that moves to make everything a simulacrum? How does one resist the joys of marketing?

“Fifteen Million Merits” ends with Bing looking outside. It is not clear if anyone in this world ever goes outside, but the outside world does not appear to be uninhabitable. It appears to be lush. (Unless this, too, is but a representation, and those are not windows, but screens?) What is more important is the symbolic function of this closing shot: it presents an outside to the society we have been shown, not as somewhere that one goes, but as something that one looks at. It is another commodity, another image: nature itself as a part of the spectacle.

It’s been awhile when I saw it so I might not remember it correct but I got the sense that it was the first time the judging panel suggested porn. Wether or not it was so, that act was what stood up to me the most in the episode. Abi is as innocent, pure and “real” as anything can be in that society (her voice is good but not spectacular by any means; her voice is not what people responded to), and the only way the society (and the panel) is able to react is to drag her to their level, or if possible, even beneath it.

Yes, it is very much implied that this was the first time the Hot Shot panel made a suggestion like this. It is not clear, then, how the previously existing Wraith Babes got into that, though. I agree about that being a central moment. I will also admit that I found myself to be less sympathetic to Bing as I watched again in preparation for writing this than I was the first time I saw the episode a few years ago.