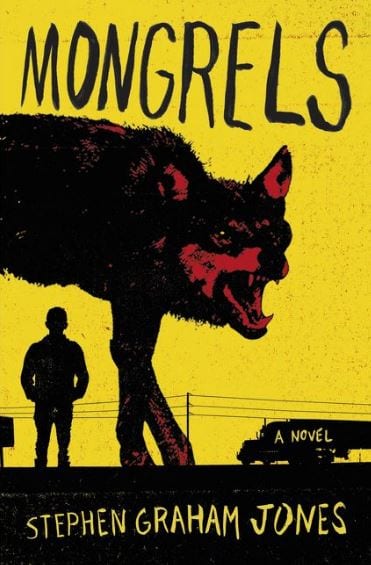

Stephen Graham Jones is the author of no less than sixteen novels and two hundred and fifty short stories. His novel, Mongrels, was nominated for Bram Stoker and Shirley Jackson Awards as well as being named a best book of 2016 by Book Riot. He received this year’s Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Long Fiction for Mapping the Interior. Mark Frost and David Lynch were included in Bram Stoker Award nominations this year in the category of Superior Achievement in a Screenplay for Twin Peaks, Part 8.

Stephen offered 25 Years Later some of his time to discuss a David Lynch film that stands out for him. I was honored to be able to discuss Lost Highway and his book Mapping the Interior. For context, Mapping the Interior is a long fiction piece about a single-parent Native American family plagued by their past and present circumstances. The protagonist catches a glimpse of his father’s ghost passing in the night, leading to a horrific emotional journey where admitting his return may become less inviting and more invasion.

Rob: First, congratulations on your Bram Stoker Award in Superior Achievement in Long Fiction for Mapping the Interior.

SGJ: Thank you very much. It’s quite an honor.

Rob: When did you find out about that?

SGJ: Right as it happened. People from the banquet were texting me.

Rob: We’re going to speak to Lost Highway as I know that’s an influential David Lynch film for you, but how did you come to the art of David Lynch? Was there a first work you remember, realizing it was by his direction or not, and what was that impression?

SGJ: I think my, I don’t know, fascination with Lynch, or whatever you want to call it, starts with Lost Highway, actually. I’d watched some Twin Peaks in the 90’s, just kind of jumping from random episode to random episode, nothing continuous, and it was cool stuff but I didn’t know who Lynch was. And I was there opening day, in I guess ‘97, when Lost Highway came out. My wife and I were, we were two of three people, I think, in the theater in Tallahassee, Florida. And I watched it, and I was hooked ever since. Since then, I went back and watched Blue Velvet, Eraserhead, kept up with Mulholland Drive, even The Straight Story. You know, I think I watched all of it, but Lost Highway is where it starts for me.

Rob: How is Lynch’s work aging for you?

SGJ: Oh, wonderfully, wonderfully. It’s such a compelling little story. Uhm, and then, you know, I hopped online to see how people have been reading it these last few years and it seems like nobody else reads that movie like I read it, I guess, which I thought was weird because I didn’t think my read was in any way, I don’t know, unconventional, you know?

Rob: Right. So what is that kind of reading, or what do you find that …?

SGJ: I read it as that first act, up until Fred goes to prison is the real part of the story. Like people say it’s a parallel narrative, but to me it’s not at all parallel narrative. It’s nested narrative. It’s the first act that really happens. He’s jealous that his wife is having an affair. He kills her, and because he likes to remember things the way he likes to remember them, he tries to do that, but it’s not reconciling. So then he kind of, uhm, you know, has his bad migraine, which is a rupture in reality for him. And at that point, we duck into his head and he rebirths himself as the cool guy who wears the leather jacket and has the bad car, a motorcycle, a girlfriend. He has lots of sex. So he’s like living in a little dream place, trying to restart his life. But his old fears and people keep rising. You know, Renee rises as Alice. Blake, or the Mystery Man, crosses over. The Mystery Man to me is just his own, like, jealous impulses, you know? The same way that Robert Loggia is, what, Mr. Eddy, who is also Dick Laurent; he’s just, he’s power to me. So the first line, or the line that Fred gives himself through the intercom at the first of the movie—“Dick Laurent is dead”—that’s just to me a way of saying you have no power. He’s being cheated on, and he feels he has no power. And it starts there for him, and it gets worse and worse. And he tries to live in a happy place in his head, but it doesn’t work, it breaks down as all happy places we try to live in in our heads do.

Rob: Right. No, I think that is a spot-on read. I think the idea of people, ugly reality butting its way into his little fantasy is new to me and the idea of the strength with the power of Dick Laurent … Yeah, I think that scene at the end as he’s driving away and yelling, I’ve at least heard it interpreted as—you know, last year was the 20th anniversary, is that right?—and I heard it said at that time that maybe that’s him in the electric chair, but to him, in his mind, he’s speeding away.

SGJ: Yeah, exactly, yeah he can’t reconcile. That’s why he’s so worried about Alice having a history in porn because he wants to, he wants to control all of her. And he likes to remember things the way he wants to remember them, so he wants to remember her the way she’s always been with him, you know, but she has not always been with him. And … Fred’s not a good dude. We still feel sympathetic for him, but yeah, he killed his wife and dismembers her and checks out, you know?

Rob: Well, yeah, and that is the fascinating part because Pete is somewhat sympathetic. He is kind of out of his element, but where he’s coming from, that is not the truth whatsoever. And I feel like we saw that in Mulholland Drive, though it took me some time to kind of wrap my mind around it, and it was like whoa, there’s a certain point of this that is reality, and there’s a certain point where every time someone begins being ugly, or someone from her past, reality comes in, they begin to wear red and black, so you watch those colors.

SGJ: Yeah, Mulholland Drive, it felt to me like David Lynch didn’t like the way people were reading Lost Highway so he thought well, let’s do it again, try to make it clearer.

Rob: That’s a fascinating way to look at it, so the next question—I’ll just go by script on this. I think I ask about aging because Lost Highway is probably a very 1990’s experience for you and for me. When we hear that music, it’s firmly in our context of what the late 1990’s looked like and sounded like. In Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks, we all notice its throwback styles, almost the 50’s American facade meets the 80’s and early 90’s. But with Lost Highway, it’s firmly in the 90’s in my estimation. Is there a statement about its decade that does anything for you at all?

SGJ: When I watched Lost Highway the first time, I didn’t know that was Marilyn Manson. I just thought it was an actor. I didn’t know who that was. So now when I watch it, I’m like yeah, that’s cool, it’s Marilyn Manson, you know? And I guess I’m familiar with some of the songs. Of course, didn’t Badalamenti do the score for this, right?

Rob: Oh yeah, I believe he did the score and compiled that music.

SGJ: Yeah, it’s really good. As far as like dating it or feeling 90’s, this time, one thing I noticed, that I didn’t notice the first time, is you can see especially when Pete is driving on his motorcycle in nighttime Los Angeles, I guess, all the lens flare stuff going on. Like I never was aware that was a thing. I was listening to a podcast the other day with John Carpenter where he was talking about how some of his early films had that, and he said he wasn’t doing it to be artistic. He was doing it because of production costs and low budget. Then, you have J.J. Abrams doing it in Star Trek, and it’s a big deal. So there is stuff that I notice in the film, but it’s not about its aging; it’s about how things have changed in the last twenty one years.

Rob: In Lost Highway, in thinking about aging or in decades, we’re looking at memory. We see a medium for its storage in VHS cassettes of the time, that handheld camera. In the film, Fred Madison (Bill Pullman’s character) tells detectives “I like to remember things my own way.” The detective asks: “What do you mean by that,” where upon Fred responds “How I remembered them. Not necessarily the way they happened.” How does this read to you in the context of the film and perhaps even as an influence in your own work, memory?

SGJ: Oh yeah, that’s a good point. I’m trying to think if any of my books have that kind of stuff going on … Let me think … Yeah, I guess Mongrels does, really. There is a line at the end of Mongrels where the narrator and his aunt are talking and he says “I had you fight bears,” and she says “Maybe I did fight bears,” which kind of casts a light of uncertainty back on everything that’s happened before. You know, was it made up? Am I telling the story like it happened, or am I telling it like it felt? For me, I’ll always pick how the story felt. I don’t think the fact, or how something corresponds to reality, I don’t think that really has any impact at all. There’s the truth of the feeling. Hopefully that is throughout all of my work anyway. Hopefully, it’s like a guiding principle.

of Mongrels where the narrator and his aunt are talking and he says “I had you fight bears,” and she says “Maybe I did fight bears,” which kind of casts a light of uncertainty back on everything that’s happened before. You know, was it made up? Am I telling the story like it happened, or am I telling it like it felt? For me, I’ll always pick how the story felt. I don’t think the fact, or how something corresponds to reality, I don’t think that really has any impact at all. There’s the truth of the feeling. Hopefully that is throughout all of my work anyway. Hopefully, it’s like a guiding principle.

Rob: It sounds like the kind of principle that I would apply to most of Lynch’s work that I watch, or at least as I experience him creating it in my mind—is that the feeling is more important.

SGJ: Yeah, oh for sure. But that’s why he always has that syrupy music. He’s putting you in a place, and it doesn’t matter if there is actually a red curtain and somebody dancing or anything; it’s what that provokes in you, what that elicits from you.

Rob: Do you find yourself wanting answers to the mystery in Lost Highway, or do you find yourself leaving it with admiration, awe, or frustration because of the information left unstated?

SGJ: No, I find myself completely satisfied. I don’t really think I … Let me think, am I closing with any questions? I guess I … I guess I could ask who are the cops chasing at the end of the movie, but really I don’t think the cops are chasing anybody because the cops are in Fred’s head. You know, one thing I always wonder, when Andy dies—he’s, you know, the thin mustache guy—Andy and Blake are the only two people to actually kind of cross over, I think, from reality to dream. They cross over intact anyways. I always wonder when he dies on that corner of that coffee table. Why did he die that way instead of fifty other ways he could have died? I always feel like Lynch is paying homage to some key scene from cinema that I haven’t locked onto yet. I feel like there is a dialogue going on there that I’m not privy to, but I don’t know if I need an answer. I’m happy to stumble across it someday.

Rob: Yeah, in Twin Peaks, this latest iteration—so, you got to see that or not?

SGJ: I have not, no.

Rob: Okay, so I won’t go too far into it since it’s still new to you. A lot of people thought about it, or at least I saw a presentation on it at the Southwest Popular Annual Conference, where the guy who talked about it (Mike Mills) said it was almost like David Lynch self-curated his own retrospective across his films and in Twin Peaks, and so I was trying to defend it, the new series, for an article we’re writing. And I talked about, you know, there is a certain omniscience you have by the end of it, that if you go back, you’re in a new head space that you don’t get to escape. And that made me think of the David Foster Wallace line, I think it was in This is Water, where he talks about when an adult kills themselves with a firearm, is there any wonder that when they shoot themselves in the head, they are shooting the master, the evil master. And so that killing, the slicing open of the head—I don’t know; I’m probably reading too much—but I would go somewhere like that. But there is a chance there could be a painting out there as well.

SGJ: Yeah, there is, isn’t there? There could be so many points of origin, talking Lynch.

Rob: I’m going to go ahead and just put it out there that I believe we see definite Lost Highway influences on Showtime’s Twin Peaks: A Limited Series Event, and long before that—whatever lightening David Lynch caught in its making—in Mulholland Drive. Have you found this effect in your own writing, meaning that in exploration through writing you stumbled onto an idea that resounds or finds footing in future works as a recurring or continued feature?

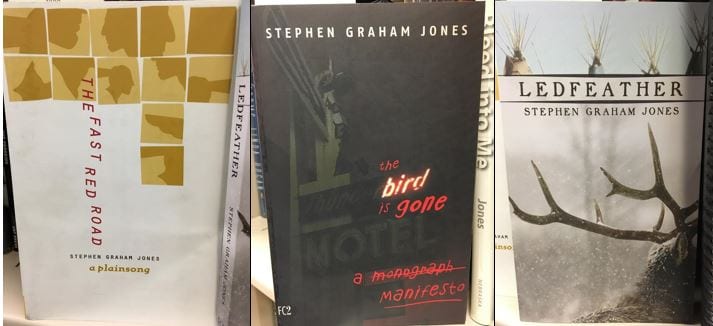

SGJ: Oh yeah, definitely, like I have three novels: The Fast Red Road, The Bird is Gone, and Ledfeather, which to me, to me they are related to each other the same way Lost Highway is related to Mulholland Drive, possibly. Like I wrote Fast Red Road, and I thought I did it the way I wanted to do it, but then, people didn’t seem to be accessing it the way that I halfway meant, so I thought “Oh, I’ll just do it better.” So then I wrote The Bird is Gone, and I thought I’ll pare it down. I’ll cut the book. It will be a third as long. It will be more direct, so it will be straightforward, what I’m saying, but still, it evidently wasn’t. So then I did it a third time with Ledfeather, and with Ledfeather it finally landed like I meant it. It landed with the audience that way I wanted it to land, so I quit telling that story.

Rob: Okay, wow, that’s great. Is there anything more you’d like to discuss about Lost Highway before we briefly turn to “Mapping the Interior?”

SGJ: The one other question I always have—not always, like I think about this every third Thursday or anything—but I wondered it last night, and I remember wondering at the first screening was when Renee is walking around the house in her house robe in the first act, in those first few scenes, why is she wearing those high-heeled shoes? That does not make any sense to me. If you want to be comfortable in a robe, I understand, but why put high-heeled shoes on? So I never can understand that. It could just be that Arquette is not tall, and they wanted to make it easier to frame with Pullman, by having her a little, you know, four or five inches up, but I don’t know. So that always freaked me out a little bit.

Rob: Yeah, I don’t know if I have a good answer for it either. I think back, that part of David Lynch’s directing style, and I guess he would have directed that scene, yeah, it would have been in the pilot of Twin Peaks, the original. You know, you get that good look at Audrey’s shoes, those saddle shoes, as she’s getting out. And in The Return I know there was a feeling for a little bit—and I’m not going to take it away from the interpretation—that there was kind of maybe a Wizard of Oz thing happening here, as we know he likes from Wild At Heart. And it’s like, well gosh, you see these red shoes and all of us, as it was airing, we’re all getting online, and it was like “Oh my god, red shoes, red shoes!” It’s Dorothy’s moment, right? Or if Cooper can find his shoes, we’re going to have this whole return, we’re going to have this moment.” And so, there is something to shoes. You just have to kind of keep that in your cache and just go with it. I don’t think there was anything like that in Mulholland Drive, though. I would have to look at it.

SGJ: You know, one of my favorite moments in Lost Highway, which I didn’t recognize until I was watching it yesterday—I’ve probably watched it four or five times across the years—is when Pete is … I think he’s at the shop and the radio is on. Fred’s saxophone solo comes through, and he acts like it hurts his ears. Then, he turns it off. It’s just the reality of it he doesn’t want to acknowledge. It’s forcing its way through every facet it can, and now it’s just attacking him. I think if you watched that movie really slowly that it is just going to be so densely packed with that stuff.

Rob: That’s how Lynch has come to me over the years, and I don’t know if it’s my maturity. I can see it through a much clearer lens than I used to be able to. Maybe I have a perspective now.

SGJ: It was neat; just a couple weeks ago, I re-watched Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, and Kill Bill 1 & 2, and it was neat trying to position Lost Highway amid all of those on a continuum. I’m not saying Lost Highway was in a dialogue with Tarantino or his work, but there does seem to be a similar, I don’t know—aesthetic, like a pulpy aesthetic, like an ironically pulpy aesthetic.

Rob: Well, I was thinking, yeah, and you say pulp, and it’s very uniquely that 90’s noir, that washed out darkness. I don’t know how to describe it, and then kind of linking those, you would have Wild At Heart in there along with True Romance, Natural Born Killers … You know, there was definitely a Bonnie & Clyde 90’s roguishness … there was something about true love being truly violent and disgusting or something.

SGJ: Yeah, I think there was.

Rob: So here is how I want to bridge the discussion. As I said earlier, you just won a Bram Stoker Award for Mapping the Interior. That is a horror award. You have been in multiple anthologies, some speaking to the “Weird,” as a genre or tale. Would you categorize David Lynch films in a horror genre? How about your work? Is there room for misrepresentation?

SGJ: That’s a good question. I think that … I think Lynch’s stuff probably does veer more horror than anything else, but the type of horror that he is engaging is not the jump-scare horror. It’s not survival horror. It’s more like, it leaves you with a feeling of existential dread. He kind of … you don’t question reality like is there really Cthulu. You question reality like is this real or is this Memorex?

Rob: Right. So what I was thinking, and this is going to lead into a really fun question here shortly … I was thinking that in your work, it straddles that line of cadence in your sentences that speaks to a literary mode. And what I’m saying by that is that it’s thoughtful in its intent, in its cadence, and of its audience. Still, you allow it to have genre elements, but elevated. And so it made me think back to a C.S. Lewis essay, of all things, titled “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s To Be Said (On Stories).” Do horrific tales or elements do the same?

SGJ: Yeah, I see what you are saying. My go-to example there is that I can tell you a story about me and my dad watching basketball in our living room on a Sunday afternoon, and my dad’s brother-in-law will get drunk and come down the road and kick down our door and get in a fight with my dad. They’ll tear up the living room, and it will be a terrible scene. And that’s the literary version, I guess. But if I tell you a story where me and my dad are hanging out in the living room, watching basketball one Sunday afternoon and a zombie shambles across the lawn, and he comes in there and starts trying to eat us, then I think, hopefully, that’s trying to deliver the same emotions or feelings. But it’s wrapping it in a zombie story, which is kind of inherently a good time. I think genre is really useful as a device to smuggle across what you want to smuggle across but do it in a way that is interesting.

Rob: Since we spoke of Lost Highway and memory, I feel like memory is also an important element in Mapping the Interior. This character wants the familiar as he remembers it to return, but what comes back may not be as hoped for. It might be unfamiliar. I have a paper that needs to get published on Twin Peaks and Lovecraft’s “cosmic horror,” some possible connections there. In that I quote three elements that must occur in his particular brand of cosmic horror—and this is by a gentleman named Clements; I don’t have the full thing here–“Narrators who manage to get past the wall must either die, return to the everyday world, or become a monster.”[1] Considering David Lynch’s horrific elements and what I’ve read in yours, are we stumbling into “memory horror?”

SGJ: Oh yeah, that’s neat.

Rob: I mean, we have body horror …

SGJ: I like that. In Mapping the Interior, I mean, I guess this will be a little spoilery if you haven’t read it, but he becomes the monster of those three options. I think … yeah, I think memory … We might be broaching into a new age where memory horror has a lot more import for the audience because the way we live right now, the way I live anyways—I see a lot of people doing it—is if I have a meeting next Thursday, I don’t say to my head “hey, remind me,” I say to my phone “remind me.” I’m putting all of my memories in my phone, and who’s to say my memories are in little satellites that circle around me. That’s … its … dehumanizing is not the right word, but it’s weird. It’s like we’re spreading ourselves out, and the question is are we spreading ourselves too thin. If my phone has a glitch and changes my scheduled appointment from Thursday to Friday, I’ll never … I mean, I’ll miss my appointment. It will be changing reality kind of, because the memory, my externalized, the memory I’ve given away or I’ve trusted to someone else is changing. So yeah, it could be that Lost Highway is getting more pertinent with our current culture. In the late 90’s, I mean, there was video recording, which Lynch evidently hates video cameras and so that’s kind of what he was poking fun at, but, uhm, I think the idea of everybody having a video camera that we can document all of the moments of our life, you know, but it’s … I think, yeah, it probably does have a lot more weight right now. That’s a neat way to think about it, the memory part. If you can manipulate memory, you can manipulate the past. You can change who a person is because that’s how we persist through time. We tell ourselves stories about what happened in the past, which has a conclusion about who we are now. If you can change those events, you can change everything.

Rob: Well, thank you for your time. That was really great. Did we take up too much of your time?

SGJ: No, that was great. Thank you.

[1] Clements, D., & Sussman, Henry. (1999). Cosmic Psychoanalysis: Lovecraft, Lacan, and Limits, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

“pare” not “pair”. 🙂 wonderful interview, great questions. thank you.

I think someone else read LOST HIGHWAY as you did:

“…a desperate flurry of denials. Perhaps, like the long first section of Mulholland Dr., that’s what Lost Highway is… Dayton’s portion of the film veers towards naturalism. Like many aspects of the section, this mode can itself be seen as an attempt to take control of threatening elements in the preceding narrative…”

Ramsey, thanks for pointing this out. Absolutely, my read on the interview is that in a quick search of impressions, maybe online, maybe in person, Stephen had not stumbled onto these deeper perspectives that matched his own. Our partner podcast Twin Peaks Unwrapped had a stellar episode for the 20th Anniversary, which landed very close to these ideas. Yeah, good stuff.