“I like Bergman, but his films are so different,” says David Lynch at one point in Lynch on Lynch. “Sparse. Sparse dreams.” He’s just been effusively discussing how Fellini’s films make him dream, in magical and lyrical ways. Which leads him on to Bergman. Bergman’s work has another dream quality to it and Lynch gets at the kernel of that in appropriately few words. He’s admiring, yet more distant from Bergman, perhaps unconsciously suggesting that Bergman’s cinematic vision is more singular, less able to influence.

Explodes in Pictures

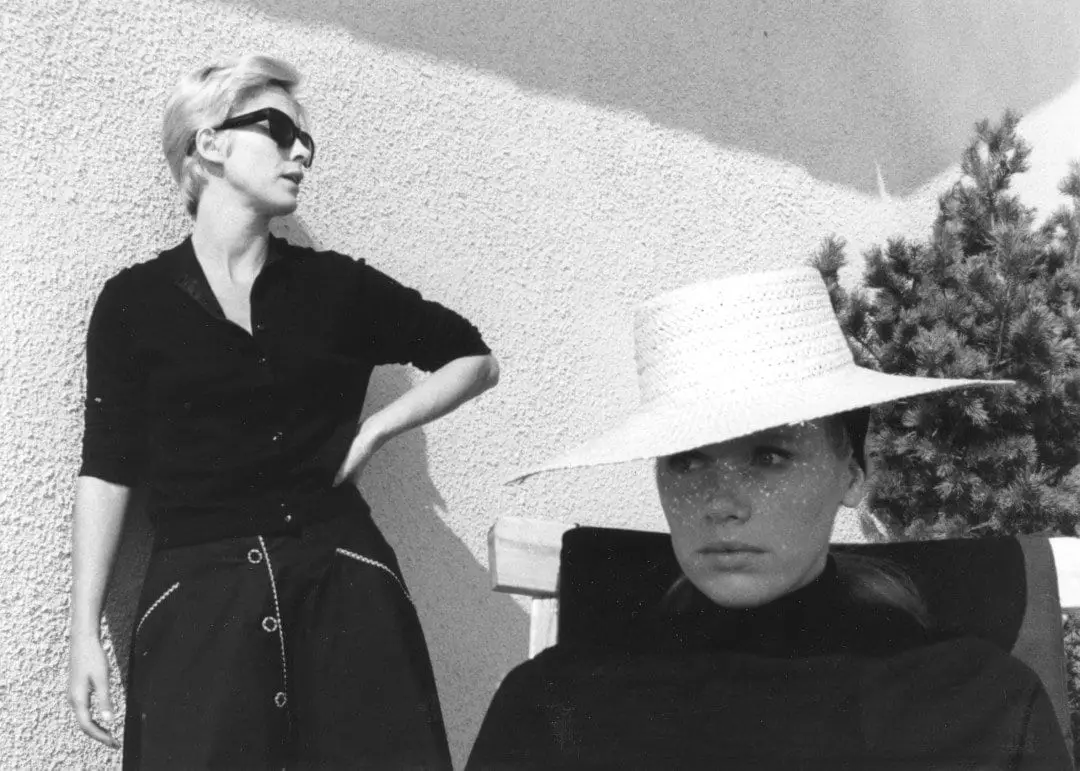

Persona (1966) is Bergman’s most experimental film, or at least his most experimental in a certain direction. It is high modernism to the postmodernist games of the French new wave. Persona does share some superficial connections to the mid-1960s work of Godard and co in its deconstruction of cinema, yet Bergman’s approach goes far beyond surface self-referentiality. Instead of pulling apart and reconstructing the fiction of cinema, Persona sees how far cinema can go psychologically. Bergman doesn’t merely dip his toes into unknown waters; he dives right in and takes great gasping breaths of the stuff.

Persona begins in confrontational manner; the infamous opening sequence up to and including the titles is an avant-garde work in its own right. “The strip of film that rushes through the projector and explodes in pictures and brief sequences was something I had carried around with me for a long time,” explains Bergman in his book Images: My Life in Film. Bergman the director is represented by a child alter ego as he peers up at a screen, tries to reach into it. The screen oscillates between two key images that are one: the faces of Elisabet Vogler (Liv Ullmann) and Nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson). Who are they and indeed – running parallel – who is she, that suggested combination of the two? Lynch asks similar questions in Mulholland Drive, which is the closest comparison to Persona within his oeuvre. That Bergman poses these questions immediately before the title card is not insignificant. The titles (black type on overwhelming white, itself a reversal of expectations) are attacked by a percussive modern classical piece and interrupted by a series of flash cut images.

Bergman doesn’t ease viewers into the dreamscape of Persona as Lynch does with Mulholland Drive. Nevertheless, each work successfully submerges the audience in its dream on its own terms.

Removal of the Medium Shot

The discordant avant-garde prologue is out of the way, but its impact over the proceeding narrative cannot be underestimated. Astute viewers may note that the opening sequence offers glimpses of ideas and themes that will run throughout Persona. It acts as a summation before the fact and can only reasonably be seen as such upon a second viewing. Furthermore, although the film appears to settle into a more natural pace, one should not be fooled. Scenes run on and then Bergman cuts into them without warning; dreams are not signalled as separate from reality; and the narrative is still made up of film running through a projector, which Bergman is not done reminding us of.

Out of the avant-garde and into a hospital. Alma, a young nurse, is given an assignment to care for actress Elisabet Vogler. The doctor (Margaretha Krook) explains Mrs Vogler’s unique case. In the middle of a performance playing Electra “she fell silent and looked around as if in surprise.” She has not spoken a word since and is recuperating at the hospital. Close-ups from different angles on Alma accompany the doctor’s dialogue, including a shot from close behind Alma that has the doctor out of focus in the middle distance. This sets out much of the cinematic grammar that Bergman employs in Persona.

Bergman and his cinematographer Sven Nykvist had earlier “arrived at the conclusion that medium shots in film were boring and unnecessary. The removal of the medium shot was taken to radical lengths in Persona. The film consists almost exclusively of close-ups and long-shots” (Ingmar Bergman A – Ö). Indeed Persona doesn’t feel or look like anything else; even when compared to the rest of Bergman’s body of work.

Constant Hunger to Be Unmasked

Alma considers turning down the assignment, as she worries that she will not be able to cope mentally against Mrs Vogler. The other woman’s silence “shows great mental strength.” In Mulholland Drive, it is Betty who takes on the nurse role, helping rehabilitate the almost-mute Rita. Of course Rita’s silence is not a complete one, yet she is nevertheless unable to tell her own story. When Alma first meets Mrs Vogler, she provides the other woman with a truncated autobiography, her talk overcompensating for Mrs Vogler’s intimidating silence. Again, this is akin to Betty, who overcompensates for Rita’s lack of story – she provides Rita with a narrative based upon supposition, that she is her aunt’s friend.

Afterwards, Mrs Vogler is lying in bed, head tilted toward the audience, eyes searching beyond. The camera holds close on her as the room darkens, shadows enveloping her face. Bergman doesn’t quite allow the scene to drop fully into darkness before he cuts to Alma. Alma switches off the light in her room, plunging the screen into the dark. But she cannot sleep and turns the light back on. Alma speaks aloud – to herself, to us – about how she will marry her sweetheart and have a couple of kids. Accompanying her voice is the sound of a ticking clock. Here Alma presents an uncritical view of her life to come; it will feed directly into her confessional later on.

The real world encroaches on Mrs Vogler’s self-imposed exile. Firstly via the television and a report on the war in Vietnam. Then a letter arrives from her husband, containing a photograph of their son. Mrs Vogler tears the picture in half. The tearing of the letter leads to another cut in close-up, staying on Mrs Vogler but shifting in time. The doctor suggests that Mrs Vogler and Alma leave the hospital and stay in her summer place by the sea. First she offers her assessment of Mrs Vogler’s condition, couched in rather metaphysical terms. “You think I don’t understand?” she tells Mrs Vogler. “The hopeless dream of being. Not seeming to be, but being. Conscious and awake at every moment. At the same time, the chasm between what you are to others and what you are to yourself. The feeling of vertigo, and the constant hunger to be unmasked once and for all. To be seen through, cut down, perhaps even annihilated. Every tone of voice a lie, every gesture a falsehood, every smile a grimace.”

Words which could fruitfully be applied to a reading of Mulholland Drive.

Summer House by the Sea

Bergman himself narrates the transition between the world of the hospital and that of the summer house by the sea. Walls have been broken down although silence has not been broken. Mrs Vogler has become Elisabet to Alma; they now coexist somewhat like Betty and Rita. The two women are sitting outside. Elisabet prepares mushrooms and consults a book on them (one wonders whether Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread references this rather minor moment in Persona, transforming the idea into a key part of its own narrative). Elisabet takes Alma’s hand, examines it, to which Alma responds: “Don’t you know it’s bad luck to compare hands?”

Bergman shows us various scenes between the two women, with Alma constantly talking, becoming more and more comfortable as she does so. Elisabet has become some sort of muse, teasing words out of Alma. “It feels so good to talk,” says Alma. “It feels nice and warm. I’ve never felt like this in all my life. I’ve always wanted a sister.” Who exactly is the patient here?

Tell Don’t Show

Bergman toys with the notion further, when he has Alma sit in an armchair making a confession to Elisabet, who is sitting up in bed across the room. Elisabet may sit as if on the psychiatrist’s couch, yet she is the silent psychiatrist here. Alma tells Elisabet her most intimate story, describing a foursome she and another girl took part in on the beach. Bergman flaunts the cinematic rule of show don’t tell; this is cinema at its most erotic. Laura and Donna down by the water with the two guys in The Secret Diary of Laura Palmer makes for an intriguing comparison.

Alma is then lying next to Elisabet, weeping. She has been telling herself comforting untruths and this has exposed a wound. Like Laura Palmer, Alma wonders if there are two hers, a good and a bad. “Is it possible to be one and the same person at the very same time – I mean, two people?” Mulholland Drive is an expression of that very question.

The scene continues through the night and into morning. Alma is digging for truths. “People should be like you,” she tells Elisabet. “ You know what I thought after I saw a film of yours one night? When I got home and looked in the mirror” – Rita looking in the mirror and seeing the Gilda poster, from which she borrows a name, an identity – “I thought, ‘We look alike.’ Don’t get me wrong. You’re much more beautiful. But we’re alike somehow. I think I could turn into you if I really tried.” Perhaps the reverse, with all the ambiguity that implies, is true.

Face a Mirror

The lonesome foghorn blows as Alma finally goes to bed. Fog has seemingly crept indoors – the wind tugs at the light drapes, all the doors are open. The space is intimate but vast, inside yet outside – something Lynch has a miraculous ability to convey also. Elisabet wanders into this dreamlike realm. She looks upon Alma before stepping through into the other room. She turns as Alma sits up in bed – whether Alma is awake or not is rather beside the point. They look upon one another and move closer together; Alma rests her head on Elisabet’s shoulder. Turning, the two women face a mirror – us, the camera – and Elisabet runs her hand slowly through Alma’s hair, as if studying and altering her image at the same time. Alma’s hand reaches up for Elisabet’s hair behind her and they lean into one another, creating what is now an iconic cinematic image. Elisabet goes to kiss Alma’s neck and the scene fades to black.

It’s less explicit in sexual and narrative terms than when Betty and Rita make love in Mulholland Drive of course. The Persona sequence is structured in a more obviously dreamlike manner in regards to the scenes preceding and following it. However, Lynch’s film operates in a completely different way, with the naturalistic posing as dream and vice versa. Betty and Rita are not allowed to reach morning – Club Silencio and the blue box prevent the natural transition from night to day. No such barriers for Alma and Elisabet. If anything, morning keeps on coming around; days and nights becoming indistinguishable from one another.

Morning at the beach. Alma in the distance. Elisabet stands up into frame with a camera. She takes a photograph of us, the audience. “Elisabet, did you speak to me last night?” asks Alma. Elisabet shakes her head no. “Were you in my room last night?” Again, no.

The Film Burns

A point of crisis arrives when Elisabet asks Alma to send a letter for her and Alma reads it. “In any case,” reads Elisabet’s words, “it’s a lot of fun studying her.” Alma’s incessant chatter dries up. She breaks a glass and leaves a shard for Elisabet to stand on.

It is at this point where Bergman steps in once again and the film breaks down. Alma stares out as her face on film burns away to white. Backwards dialogue is heard. Flash cuts of images from the opening sequence appear. Then the film settles in on an eye, pushes in through the veins and back out to blurred drapes, everything out of focus as Elisabet walks through the room and back. Focus returns as Elisabet goes down to the beach looking for Alma. Alma cannot easily forgive.

Separates Them

The two women are at odds; Bergman separates them. Alma sits by the water. Elisabet paces the house. Alma is violently dreaming. She shakes herself awake, stopping short of becoming as Fred Madison in Lost Highway and shaking herself into another identity there and then. Elisabet is a shadow. Someone is shouting for her. Alma goes to see who it is and she becomes the shadow. The man is Elisabet’s husband, yet he addresses Alma as Elisabet. Elisabet, dressed in black, walks up and stands behind and to the side of Alma. Part of Elisabet’s face is obscured by Alma’s. Cut to after Alma and the husband have had sex; Elisabet’s face remains in the same position in shot, not bearing witness, but staring out at the audience, almost superimposed.

“This is shameful, all of it!” Alma cries out. “Leave me alone! I’m cold and rotten and indifferent. It’s all just a sham and lies!” As she speaks the camera moves close in on Elisabet.

Was the foursome an infidelity from a less recent past, come back to haunt her, exposed as part of a recent trauma. Is she – Alma/Elisabet – digging into who she really is and not liking what she finds? Regardless, Bergman returns us to the two women and they are ostensibly Alma and Elisabet again.

Draws Blood

“The confrontation,” says Bergman in Images: My Life in Film, “is a monologue that has been doubled.” Indeed, Alma is seen/heard to deliver her psychological attack upon Elisabet twice, with the camera focusing in on Elisabet in the first instance and Alma in the second. This is the real psychiatrist’s couch – the equivalent of Club Silencio in Mulholland Drive – and the outcome is that their faces are combined, half of one and half of the other. “It was a natural evolution, in the final part of the monologue,” continues Bergman in Images: My Life in Film, “to combine the two illuminated halves of their faces, to let them float together to become one face.”

Then it’s back to just Alma. “No! I’m not like you. I don’t feel the same way as you do. I’m Sister Alma. I’m only here to help you. I’m not Elisabet Vogler. You’re Elisabet Vogler.” The two faces are together again, punctuated by discordant stabs of music. Bergman holds on the twinned face before bleeding out to white.

Elisabet sits at a table in the house and Alma walks in purposefully, once again in her nurse’s uniform. “I’ve learned quite a lot,” she says. Roles are re-asserted and subsequently pulled apart. Everything has been destabilised after the confrontation. Nurse Alma cannot maintain her composure in that role. She frantically bangs gripped together hands against a table.

Alma tears her nails along the underside of her arm and draws blood. She offers her arm to Elisabet, who sucks at it. Elisebet’s vampiric behaviour toward Alma’s confession is here made literal, with a key point entering the conversation: Alma offers freely what she has. But Alma is not content to admit that and pulls her arm back before slapping Elisabet repeatedly about the face.

The Film Runs Out

Apparently back in the hospital, Alma gets Elisabet to speak the word “nothing.” Whereby Bergman transitions back to the two women looking into the mirror together before bleeding out to white.

Alma wakes up, back in the summer house. She’s no longer wearing the nurse’s uniform and Elisabet is seen to be packing. Then Alma is wearing her uniform again and also starts to pack, but where then is Elisabet? She is out of the picture. Lynch transitions down through the blue box in Mulholland Drive, which demarcates levels of reality. Bergman doesn’t mark up such lines.

Alma looks in the mirror and pushes her hair back just like Elisabet did to her earlier. She sees the other woman/her other self there with her in the reflection. The earlier sequence is superimposed upon the current, the movements creating a dreamlike effect that Lynch echoes in Mulholland Drive. Then Alma leaves the summer house – alone. There’s a quick cut to Elisabet as Electra, then to a film set where the camera comes down, back to earth. Bergman returns to Alma, who gets on a bus and leaves.

Back to Bergman’s youthful alter ego from the prologue and the faces on the screen that are each distinct yet one and the same. The film runs out.

Assault Upon Identity

Persona is a meditation on and an assault upon identity. Ingmar Bergman crafted a modernist masterpiece which essays how fragile, fraught and fractured the realisations of our selves truly are. It’s not a film to be decoded or solved, but experienced. In that at least, Bergman and Lynch are as one.