“On-Screen, Off-Screen” is our monthly film series created to showcase a more personal retrospective about some of our favourite filmmakers. Each month, one 25YL staffer will choose one of their own favourite filmmakers – be it a director or performer or writer or composer or production designer, etc – and will analyse what it is about their on-screen work that they love, and how they’ve been influenced/inspired by them off-screen either personally or creatively or artistically. Maybe one of us will write about the entire filmography of a director, or someone might choose an actor associated with playing a certain role multiple times, or maybe there’s that one soundtrack by a composer that gets them every time. This month sees Ashley Harris writing about the inspirational icon of the French New Wave, François Truffaut. Enjoy!

“Three films a day, three books a week and records of great music would be enough to make me happy to the day I die”–François Truffaut.

A neglectful family and a troubled relationship with formal education pushed François Truffaut to educate himself as a child. The lesson plan he came up with necessitated him seeing three movies a day and reading three books a week. Despite his constant struggles with the education system, Truffaut had a thirst for knowledge that could hardly be satisfied. Finding refuge at the movies, Truffaut dedicated his childhood to the cinema and employed whatever means necessary to achieve his personally crafted education experience. This dedication to the art, coupled with the magically humanistic films and the French New Wave of cinema he would usher in are among the reasons I count François Truffaut as my greatest inspiration.

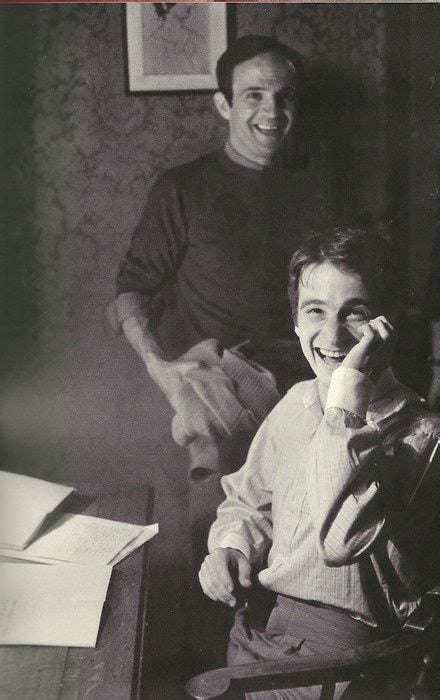

François Truffaut came into my life in the most beautifully unexpected way, and it all started with his 1962 film, Jules and Jim. I had started the second year of my undergrad late, with barely enough time to pick up a syllabus before I found myself in a screening room for Jules and Jim. The film left absolutely no impression on me after my initial viewing, or so I thought. As the months passed, however, I found myself reminiscing about the personal and emotionally raw story on a regular basis. “But not this one Jim, alright?” the simple line stuck with me, pushing me to finally get my hands on my copy of Truffaut’s masterpiece so I could watch it again. After the second viewing, I was emotionally spent by the time the credits rolled, but I was hooked on Truffaut. I enjoyed weekly meetings with the professor that introduced me to the film so we could discuss it; I wanted to immerse myself into the world Truffaut created with Jules and Jim as much as I possibly could.

The lasting impression that Jules and Jim left on me made me want to know who its creator was–who was this person that was so tuned into the human spirit that made the most beautiful film I had ever seen? As my film interests typically do, I wanted to see everything this master had ever done, until I found out he died at the young age of 52 in 1984. The realization that there would never be another François Truffaut made me slow down on his filmography so that I could enjoy the richly humanistic experience. Soon after submersing myself in his films, I began to delve into the life of the man who made them, with curiosity and thirst similar to Truffaut himself.

Truffaut’s voluminous writings on film for Cahiers du Cinéma are among the best I’ve ever read, revealing a love for cinema like I have never seen before. This isn’t to say that Truffaut never wrote an unkind word about a film, in fact, his nickname was “The gravedigger of French cinema” because his words could be so scathing. For Truffaut, bad films didn’t exist, only bad directors. It was at Cahiers where Truffaut wrote his seminal article ‘A Certain Tendency of the French Cinema’ in 1954 developing the auteur theory. Influenced by his mentor and confidant, André Bazin, the auteur theory proposes that the director is the creative force, or author, behind a film, and that directors have unique styles and themes that present themselves through each of their films. His article signaled a shift in filmmaking and opened the doors for the many film devotees writing for Cahiers to begin production on their own films. Soon after, Truffaut began working on a film of his own, a biographical tale detailing his childhood. The 400 Blows illustrates Truffaut’s delinquency as a means to avoid his home life, his school troubles, and how he found sanctuary in the cinema. Truffaut would go on to make a whole series of films detailing various biographic details of his life as his on-screen alter ego, Jean-Pierre Léaud, aged.

I am forever in awe of Truffaut’s willingness to put so much of his life on display for public consumption. The raw emotional output into each of his films is apparent and spellbinding. Cinema’s greatest humanist, Truffaut has been called, and it is easy to see why. Each of his films paints a lifelike portrait of existence within the human condition. He makes films about love, friendship, growing up, marriage, divorce, the pain of falling out of love, murder, mystery, xenophobia, childbirth, doubt, philandering, and death. No topic was off-limits for Truffaut, because he wanted to make films that resonated with his audiences, offering windows into the various perspectives of life while making a real connection during their duration. Truffaut’s belief in interconnectedness and our reliance on one another are the reasons I highlight when trying to turn others onto his work. Truffaut once said, “The man who thinks he can do without the world is indeed mistaken, but the man who thinks the world can do without him is mistaken even worse.” In films like Jules and Jim, Two English Girls, and Confidentially Yours, Truffaut explores the depths of love and what it really means to find and foster a genuine connection with someone. His belief in the human conditions and the power of our relationships is the ultimate inspiration and a large part of the reason why I enjoy his films so much.

Truffaut was the first filmmaker I knew of to place his adoration for film before a filmmaker. An accomplished writer, Truffaut wrote about films tirelessly throughout his life, something he never gave up even after achieving success as a filmmaker. He loved movies so much that he wrote a love letter to cinema with his 1973 film, Day for Night. Day for Night features a filmmaker played by Truffaut and the many trials he encounters while trying to finish his film. At the root of the venture was a deep love for film and filmmaking, clearly visible on-screen at every moment. The director in the film, just like Truffaut himself, played a man deeply devoted to cinema believing movies were the most critical aspect of life. Intrigued by the remains of a huge abandoned film set complete with several building facades, a subway entrance, and a Paris sidewalk cafe, the idea presented itself to Truffaut to make a film about the creation of a movie. This project fulfilled a lifelong wish of Truffaut’s to film about the inside workings of the demands on a filmmaker, and what it’s like to make a movie. In each of Truffaut’s films, there is a reverence and visible devotion to the cinema but no more than in perhaps the best film about films to exist, Day for Night.

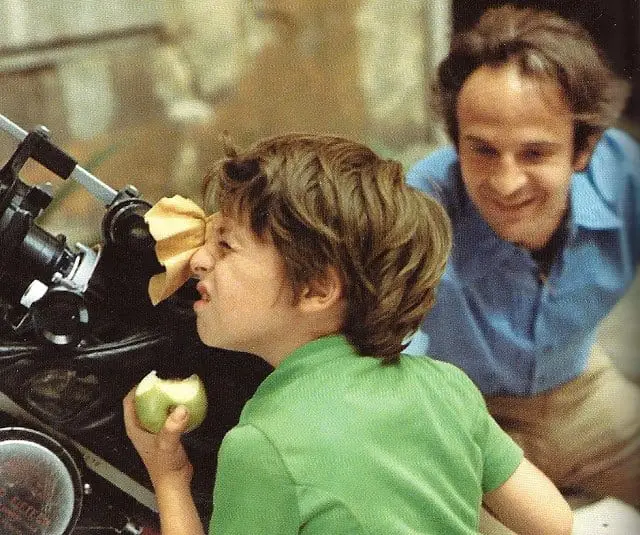

One of my favorite Truffaut stories involves his unexpected casting in a big budget American film. When Steven Spielberg was casting the role of a scientist for his 1977 film, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, he sought out Truffaut because, as he said, “I needed a man who would have the soul of a child.” Truffaut eventually accepted, despite the language barrier and he played Claude Lacombe in the film. The accounts of others that worked on that film recall him often standing in awe at the enormous set and thousands of extras. The American studio system was the opposite of what Truffaut was used to. Truffaut’s films, made in France, were on a much smaller budget and achieved with far fewer people. His own production company released his films, so he was diligent about keeping costs low on each set. Close Encounters of the Third Kind marks the only film that Truffaut acted in that wasn’t his own, and he plays a pivotal part in Spielberg’s film. I’ve never seen a Truffaut film screened in a cinema, so I’m not ashamed to share that I cried upon seeing Truffaut on-screen when Close Encounters played at an anniversary screening last year.

I know exactly what Spielberg saw in him; each time Truffaut’s Claude Lacombe is on-screen he exudes a youthful energy that radiates childlike innocence. When he encounters the aliens, he looks upon them with awe, his face capturing the incredible magic one imagines taking over in that situation. I often wonder how it was that Truffaut was able to harness the “soul of a child,” as he did his whole life not only based on Spielberg’s perception, but also the accounts of many that knew him personally when his childhood was so grim. How is it that one can rebound from a father who left them and a mother that seemed only inconvenienced by her child’s existence? Perhaps Truffaut wanted to give the world what he didn’t get, both through his movies and disposition, a reminder that there is more to your life than the point you are in now. Maybe he wanted to make the world a little bit brighter for all of us misfits.

I often say that François Truffaut taught me how to feel. What I mean when I say that is not that I was a replicant before I discovered Truffaut’s films, but rather than he gives so much of himself in each of his movies that it reminds audiences what it means to feel. The scale of a movie can make it easy to forget that there are real people behind them and that a finished film represents the ideas, emotions, and art of individuals coming to life. When you are watching a Truffaut film, it is impossible to forget that the film is his, and he bares his soul in each one. The Antoine Doinel series chronicles his life: The Man Who Loved Women shares his love of and for women, Small Change expresses his love for children, The Green Room shows his relationship with death and those that he lost in his life, Jules and Jim expresses his belief in love and friendship, and Day for Night highlights his passion for the cinema that saved him. In each of his films, Truffaut seeks to tell a part of his own story. The ability to put his heart on the line, to work passionately on every project he took, and to make communal that which makes us feel isolated is a brilliant gift Truffaut possessed and one that I have attempted to adopt in my own life.

There comes the point when you realize that you’re never going to know what’s going on, and the adults that you thought had it all together when you were a child were just as clueless as you are now. Those who appear to have perfect lives have bad days, but we’re all in this together, and being open and emotionally there for those around us makes each trip around the sun a little bit easier. That’s what Truffaut did for me; he reminded me that every interaction comes with multiple perspectives and seeing the world from someone else’s point of view is a monumental step in how to be a better person. Truffaut taught me that it’s okay to love profoundly or to not understand your feelings, but it’s not okay to shut the world out because no-one can do everything on their own. Truffaut helped me see the beauty in living an open life and putting your whole heart into everything you do. He taught me that it’s alright to be a fierce lover of cinema, even if most of the people I know can’t understand that. I can’t account how many times I have told people that I do my best to keep the Truffaut schedule of three films a day and three books a week who responded by sharing with me how much of a waste of time they imagined that life to be.

I don’t let it bother me anymore that the perspective from which they’re coming can’t understand mine, because we’re not all at the same place in our relationship to the human condition, which Truffaut taught me through The Last Metro. When asked when Truffaut knew he wanted to write about films or be a filmmaker, he replied, “Truthfully, I don’t know. All I know is that I wanted to get closer and closer to films.” This is my most profound takeaway from the life of my greatest inspiration. Love whatever you love with all of your being, enjoy it until it’s the most essential thing in the world because to you, it is. Get as close as you can to whatever that thing is that fills your life with the most pleasure and keep the same excitement about it. For me, like with Truffaut, that thing is film. When I need a pick-me-up, one of those sure-fire ways to bring a smile to my face will be to watch an interview with Truffaut in which he is discussing film. He comes alive and smiles with his entire face, his passion for cinema unable to be contained. I can only hope I can retain that same level of excitement into my 50’s, as Truffaut did while talking about my favorite films, of course when discussing my favorites, I’ll undoubtedly be discussing Truffaut’s work.