Hello Friends. As a David Lynch and Twin Peaks enthusiast I have spent the last 25 years seeking out content that engages me in the same way that Lynch’s work does while waiting for him to produce more work. This searching has largely taken place in a cinematic space, through the back catalogues of historical cinema, and contemporaneous filmmakers. Film Noir, Hitchcock, Buñuel, Cronenberg, Kaufman, Malick, Anderson, Gilliam, Iñárritu, Soderbergh and Van Sant have all played their part. Television shows like The Edge of Darkness, Lost, Buffy, The Wire, Carnivàle, Deadwood, and 12 Monkeys have again helped to fill this void. However, while the majority of these works are satisfying, they do not engage me in quite the same way, or create the same sense of uncertainty, that Lynch’s work does. Nor do they call into question my relationship with the work as a viewer to the same extent—that is until recent years. In this golden era of television some works have managed to do just that; if not in exactly the same way, in a very similar fashion. Mr Robot and The Leftovers in particular have pulled me in and demanded I take notice, and in doing so have occupied this unfilled space, giving me hope that other shows may do so in the future. [1]

In this series of articles I will attempt to get at the qualities that have allowed Mr Robot and The Leftovers to occupy this space. I attempt to do this by comparing how these projects appear to coalesce as narratives, whether that be at a textual, sub-textual or thematic level. In this first piece I will examine how these works force the audience to make sense of ambiguous realities that are explored, structured, and represented through the experience of the unreliable witness, and conflicted and confused protagonists. In the second article I will examine how transitional spaces, objects and things are deployed to draw attention to, and undercut, characters’ relationships with the realities they occupy. In the last article I will turn my attention to their exploration of apocalyptic and millenarian themes that frame the broader narrative arcs of these works, and the journeys of particular characters within each show. In doing so I will argue that the apocalyptic is used not to portray a prophesised coming of the kingdom of God or the end of the world, but rather a revelation that moves each character from a cosmos of fear and flux towards one of self-knowledge and an embrace of uncertainty.

On Uncommon Ground

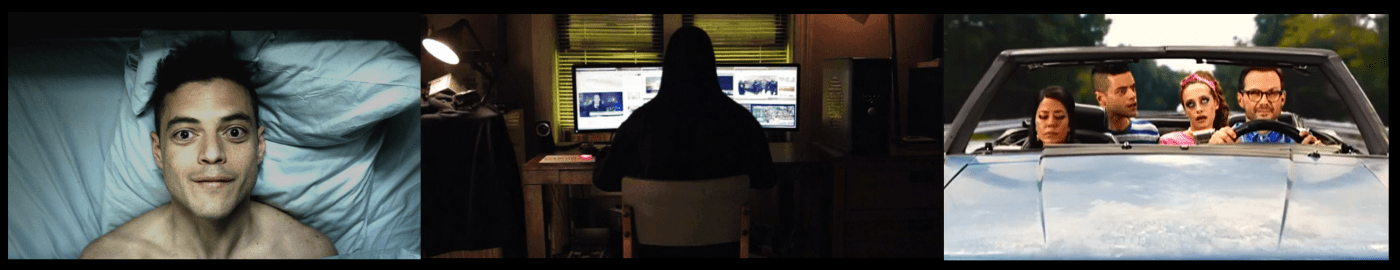

So how are Twin Peaks, The Leftovers and Mr Robot similar when to all outward appearances they are very different works? The Leftovers is an HBO show run by David Lindelof and Tom Perrotta, based on Perrotta’s 2011 novel of the same name. The series revolves around the Sudden Departure, an event in which 140 million people suddenly disappeared from the world without trace or explanation. Kevin Garvey (Justin Theroux) is our primary guide through this work and world within an ensemble cast and group of protagonists. As such, the narrative largely focuses on the Garvey family and those close to them, as they attempt to navigate the impact of the Sudden Departure in their personal lives, in an uncertain and changed world. From a genre perspective this work is presented as a drama, mystery and psychological thriller that plays out within a contentious, cosmological, and metaphysical space. Mr Robot on the other hand, initially promoted as a cyberpunk psychological thriller, is primarily, but not solely, focused on Elliot Alderson, (Rami Malek), a cyber security engineer and hacker who becomes involved in a hacktivist action to wipe out global financial and personal debt. The setting in motion of this plan and the consequences of these actions on Elliot’s relationship with friends, family, co-workers, co-conspirators, and the mysterious F-Society leader, Mr Robot (Christian Slater) frame much of the first three seasons narrative progression. Like the Leftovers, it plays out in a troubled psychological space in which we the audience, and the characters within the drama, are never certain of the validity of what we witness on screen. And it is from within this particular space that both of these projects most fundamentally resemble Twin Peaks.

On the surface, the original Twin Peaks appears to be quite different from both of these shows. Marketed as a noir-like crime drama, it focuses on the investigation into the murder of the homecoming queen Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee). It and its prequel Fire Walk With Me are however much more than this. Together these works subverted the television medium from which they grew, reshaping the night-time soap opera and melodrama by employing parody and gut wrenching tragedy within the same work. Frost and Lynch then subverted the form further by meshing supernatural, cosmological and metaphysical thriller and horror tropes into this work that they deployed through the prism of dream logic, nightmare and the transcendental exploration, changing television forever. The Return, set 25 years later, continued this trend, confounding notions of what television could be still further. Billed as an “Odyssey” it followed Dale Cooper’s (Kyle MacLachlan) return from the Black Lodge into the world, into himself, and back to the town of Twin Peaks where this mystery began. This time Lynch utilised experimental filmmaking, video, and sound art practice alongside a dedicated exploration of absurdist, expressionistic and surrealistic strategies. In doing so he delivered a work that not only challenged its own form, but also the audiences relationship to and expectations of what Twin Peaks was, is, and could be. And within this challenging of form, The Return subjected its characters to displacement in time and space, and the fracturing of identity and consciousness, spawning a multiplicity of explanations and theories vying to make sense of and find meaning within this work.

How then are Mr Robot and The Leftovers like Twin Peaks? While both works do not encapsulate the full repertoire of strategies employed by Twin Peaks, they do utilise more than most other shows, sharing a particular fondness for ambiguity and mystery missing from most other television series. Both Sam Esmail and David Lindelof have been candid about the influence Twin Peaks had on them as storytellers and filmmakers, acknowledging how it allowed them to tell stories in new ways, and how The Return has confounded these boundaries even further.[2] This influence is evidenced in how both shows have explored alternate realities and timelines within fractured narratives that like Twin Peaks leave the viewer confused and perplexed; not knowing when, where, or if, they are viewing the real or an imagined, dreamed, drug-induced, or delusional reality. As such these works demand our attention, and do not provide an easily accessible plot progression for the audience to follow. Mr Robot’s plot and directorial approach in particular, constructed through the prism of Elliot’s fractured and confused dissociative psychological state, has clear correlations with the aesthetics of Twin Peaks and its presentation of metaphysical, inter-dimensional and psychologically constructed and confused realities.

One of the most obvious components of David Lynch’s work is his idiosyncratic use of rhythms, framing and sound to disrupt how the viewer experiences each moment. He purposely does this to create visceral reaction in the spectator that puts them into the emotional and psychological space of each given scene. This can be seen in Cooper’s fall from the Red Room into the Mauve Room, and in Sam and Tracey’s watching the glass box before they are torn apart.

It can also be seen when Ed Hurley sits at the Double R thinking he will never be with Norma again; as Janey-E and Dougie have sex; as Richard Horne beats Miriam, seemingly to death, out of shot; and while Cooper and Diane have sex before crossing over into Odessa.

In all these instances, both positive and negative, the blocking, framing and timing of each shot within the edit create an unusual dramatic tension that most filmmakers never achieve. Interestingly, Sam Esmail achieves something similar, but to different effect, in Mr Robot; as a tool with which to explore Elliot’s conflicted relationship with the world around him. This can be seen most clearly in the disruption of compositional rules that are typically used to create balance within a given shot. In most conversational shot, reverse-shot edits between two actors, the character looking right to left will be framed on the right side looking through the length of the entire frame and vice versa. Mr Robot in contrast often upends this rule, as Lynch has before, having the character on the right of frame looking in the opposite direction. This creates an unsettling composition, with the subjects attention focused on negative space outside of the frame, rather than within the frame towards an object that seems somehow more tangible; creating the impression that a line has been crossed figuratively if not literally.

Again, as Lynch does, Ismail often has his characters framed on right angles looking out of the frame through the camera lens and into our living rooms. In doing so the fourth wall is broken and the spectators relationship with the onscreen action becomes one of interaction and complicity. The relationship of the subject and object becomes further complicated with the use of self-reflexive strategies that make the viewer acutely aware of the process of production, of the act of watching and of the technology that facilitates this process. This includes the use of cameras on screen, the pastiche of television shows within the main drama, and the drawing of attention to the screens we consume these dramas on; whether they be phones, computers, or flat screen televisions. The image of Tracey and Sam sitting on the couch gazing at the glass box, mimicking the screen we watch, mirrors our position in relation to the content we watch. Again, Elliot’s hacking into Facebook accounts and other people’s computers, along with his conversations with the audience again suggest that these actions and the issues he is concerned with are those that intrude into our own lives. And so a line is crossed again and one reality bleeds into another.

The Leftovers in contrast does not engage with self-reflexive techniques or break the fourth wall in the same way to tell its stories — although there are moments when characters look directly into the camera. One could argue that the performative nature of the “International Assassin” episodes also cross into the realm of pastiche. However The Leftovers more usually approaches its realities from a more realistic visual aesthetic. While The Leftovers is generally more naturalistic in its portrayal of the world and its other ambiguous localities, it is just as equivocal in its portrayal of these realities as Lynch is with those he presents to us. This ambiguity is primarily encountered through Kevin’s unstable relationship with reality, and his amnesiac and somnambulist activities, including the possible shooting of dogs, abduction, and an attempted suicide in Jarden.

While the Sudden Departure provides a context for Kevin’s unstable relationship with reality, it is also apparent that the guilt he carries and accumulates throughout the series three seasons lie at the heart of this uncertainty. Guilt: for wanting a different life to the one he had; for cheating on his wife on the day of the Departure; for being unable to prevent the suicide of Patti Levin (Ann Dowd); and for being present during the disappearance of his neighbour’s daughter (and being unable and unwilling to account for his presence during her disappearance for fear of being judged and perhaps found to be complicit). The confusion these feelings provoke is so acute that in seasons two and three Kevin repeatedly takes his own life, and allows himself to be killed, so he can travel to a metaphysical, or perhaps psychological, realm to kill a woman who is already dead, or to maybe assassinate the President of the United States in a desperate attempt to save himself and the world.

In Mr Robot this ambiguity is explored through Elliot’s conflicted relationship with the world and society, within his therapy sessions, and through his constant questioning of his own actions and motivations. We as an audience gain access to this questioning through Elliot’s internal dialogues addressed to the audience in voice over. These conversations clearly communicate that he uses narcotics to mediate his complex psychological relationship with reality, and that he is uncertain if what he sees or experiences is real or imagined. In the first episode, the first words he speaks are to the audience, whom he refers to as “friend,” and then latter defines as not real and imaginary.

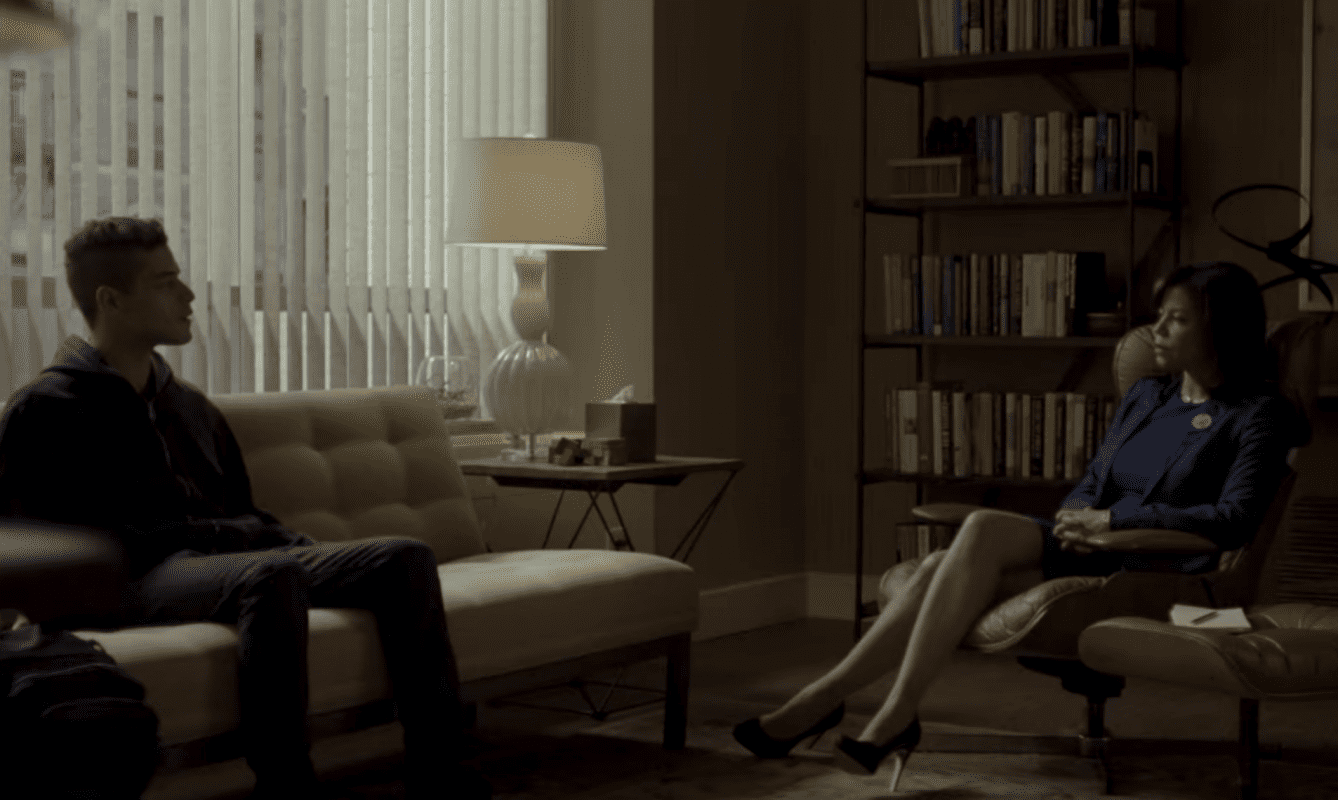

Later in the same episode, during a consultation with his therapist Krista Gordon (Gloria Reuben), Elliot is encouraged to explore his pain and anger and to negotiate his ongoing plethora of psychological disorders. This pain and anger we learn can be traced to the death of his father as a result of an industrial accident at an E Corp plant at which his father was employed. This accident, a chemical spill, resulted in his father’s leukemia, along with a host of other employees who are similarly and terminally afflicted, including the mother of Elliot’s best friend, Angela Moss (Portia Doubleday). This injustice is then further accentuated by E Corps’ use of its considerable financial power to waylay litigation and to deny responsibility for the accident or to pay compensation.

This ambivalence is further examined when Krista asks Elliot what it is about society that disappoints him so. Elliot responds with “fuck society” before succinctly communicating how “we” all experience life as spectators, anesthetized by corporate and political power structures; by our need to consume, and to project our identities into the world, blind to the injustices of that same world and the inauthenticity of our own lives. While his response is clearly articulated, it quickly becomes apparent these ideas are not communicated to Krista but instead to the viewers; his imaginary friend.

Even though this diatribe rings true its delivery also illustrates Elliot’s conflicted and potentially inauthentic relationship with himself, and his own inability to distinguish between the real and the imagined. This confusion is again highlighted when Elliot realises that Mr Robot, whom he has been plotting with against Evil Corp, is his dead father. While Elliot knows this makes no sense, alongside his initial inability to recognise him, he does not disabuse himself of this belief until it becomes apparent that his sister Darlene(Carly Chaikin) and friend Angela are unable to see Mr Robot when he can. This confusion is further compounded by the Fight Club-like revelation, for the audience first, and then for Elliot, that Mr Robot is a manifestation of his own complicated relationship with reality.

Here the synchronicity between Mr Robot, The Leftovers and Twin Peaks becomes apparent in that much of the drama explored within these shows has been generated in response to trauma, which has resulted in the fracturing of characters’ realities in one form or another. In all three shows trauma has caused the creation of alter egos, amnesia, alternative realities, and possible psychogenic fugue states, which are employed to obscure the original suffering, and to place the protagonist in a position of imagined control from which they can make the world seemingly right again.

In Twin Peaks this crisis and trauma is caused by the sexual abuse and murder or Laura Palmer. This not only affects Laura but also her family, friends and the community at large, who live with her loss and their inability to prevent her death or forestall it. Trauma is also present in Dale Cooper’s life, suffered as a result of Caroline’s (Brenda E Mathers) murder by her husband and his FBI ex-partner, Windom Earle (Kenneth Walsh), and the abduction of Annie Blackburn (Heather Graham) by Windom Earle. While the narrative of Twin Peaks can be viewed as non-linear, moving between different realities and time lines, it can also be viewed as a self-deceptive narrative constructed by Cooper to elude or help him make sense of his own trauma caused by the murder of his lover Caroline. Various arguments have been put forward to justify this reading. I have argued that this reality was created by Cooper out of the crisis of Caroline’s murder while others have suggested that Cooper is instead trying to elude his roll as murderer and abuser in the same story or in a different reality not identified within the text of Twin Peaks. It is also equally possible that Laura may have constructed Dale as part of her own self-consoling narrative to elude her own final fate, with Cooper playing the part of the white knight, rescuing her from her abuse, abduction and even death. [3] If this is true, which Gordon Cole’s (David Lynch) Monica Bellucci dream seems to suggest, Twin Peaks can, much like Mr Robot and The Leftovers, be viewed as an unreliable narrative recorded by an unreliable witness.

These self-consoling and deceptive tendencies do not however play out in the lives of a few key characters but are also reflected in the lives of many other characters; if not in the entirety of the world in which these stories unfold. In Twin Peaks this tendency can be seen in the narratives of Audrey Horne (Sherilyn Fenn), Sarah Palmer (Grace Zabriskie) and Diane Evans (Laura Dern). Each of these characters, through different circumstances are forced to take on of different forms, are imprisoned within or escape into alternative realities, to elude their pain, and perhaps in the case of Sarah her own complicity.

In The Leftovers no one is immune to the existential uncertainty generated by the Sudden Departure. All of its characters, collectively and individually, respond by seeking out answers and clarity in the form of religion and science, or by trying to get on with life, refusing to acknowledge their trauma, at least publicly, as if the Sudden Departure never occurred. The seeking out of or proffering of answers can be found in the cult of Holy Wayne, in The Guilty Remnant, and in Matthew Jamison’s (Christopher Eccleston) traditional faith. It can also be found in the creation of institutions like the Department of Sudden Departures (which, Nora Durst (Carrie Coon) works for, collecting data from those who suffered departures), in the research conducted by MIT, and in the development of Dr. Van Eeghan’s LADR technology. In most of these scenarios each response seeks out, or attempts to lay claim to, certainty.

Holy Wayne (Patterson Joseph) is presented as a prophetic figure who can take the pain and suffering away from those who come to him, along with their money, simply by holding them close. He seems to be able to do what he says, but whether this is a placebo effect or an actual miracle is never made clear. We do however learn that his prophesies of persecution and great change, and the birth of a boy who will save the world, are fabrications and delusions. His compound is raided by federal authorities on charges of previous rape rather than for his cult activity. These allegations may of course be trumped up; however, the existence of Wayne’s harem and the impregnation of its multiple young Asian woman suggest a pattern of behaviour, as well as text book cult sexual manipulation of its followers. Nora Durst, Tom Garvey (Chris Zylka) and Kevin’s own encounters with Wayne also indicate that at best he provides nothing more than the opportunity to believe in something. Yes he seems prescient in his abilities to recognise others pain, however it is possible he is just perceptive and using psychological techniques like those employed by Laurie Garvey (Amy Brenneman), in the second and third season to help people on the path to healing.

In contrast the Guilty Remnant are certain the world ended with the Sudden Departure and are determined to remind others that life is defined by the pain of not departing. This path is taken by Patti, and Laurie who are deeply changed by the Sudden Departure, but also, and perhaps more importantly, by their pre-departure lives. For example, in the time before the Sudden Departure, Laurie seemed to recognise her marriage to Kevin was coming to an end. Yet this knowledge was tempered by an unwanted pregnancy, of which Kevin was unaware, complicating her path forward. In some ways the Sudden Departure clarified Laurie’s thinking by taking the unborn child from her womb as she looked at it on ultrasound screen. Yet at the same time this apparent act of wish fulfillment magnifies Laurie sense of loss. Without sharing what she went through, Laurie attempts to continue on until in a fit of despair she contemplates suicide, then joins the Guilty Remnant. In doing so she turns her despair outward, seeking to make others remember their pain; perpetuating communal trauma so as not to be alone.

When we meet Nora before the Departure we similarly find her in a family situation that is less that perfect, with an unsupportive husband who doesn’t help take up the slack with their two children while she is having to manage family and a new job. At a particularly trying moment, she literally turns her back on her family in anger only to turn back and find them gone — husband, daughter and son. And in that moment her frustration and anger transforms into suffering. In many ways Nora responds to this loss by continuing on with her life but without faith in religion or God. Despite her daily routine and the outward projection of pragmatic stoicism, everything Nora does is done to remind her of the pain, her guilt, and her aloneness. She works for the Department of Sudden Departures, recording others’ losses, and processing their claims for compensation. She stocks her cupboards with food she used to buy for her children, then when it expires, replaces it again. She also seeks out pain, as if punishing herself, paying prostitutes to shoot her in the chest while wearing a bullet proof vest. This allows her to experience the physical pain of the impact, which in turn forces her to remember the emotional anguish she felt at her families loss. As such Nora is defined by the void in her life and the fear that future life and love will be guaranteed to bring ongoing loss and pain.

In many ways Nora’s holding on to pain and Laurie’s turning it outward can be read as acts of bad faith and philosophical suicide designed to elude the consequences of an absurd existence, instead of engaging with life and an uncertain world. They both in their own ways are seeking to keep life and its suffering at bay, or in stasis. As the series progresses, both of their positions will be challenged and they will in different ways find a way to continue on and make their lives their own.

While Twin Peaks provides the most obvious exploration of the absurd, it is also present within the Leftovers and Mr Robot. As Caemeron Crain notes in Let The Mystery Be, The Leftovers continually grapples with the notion of absurdity and does so by exploring the consequences of, self-deception, the Kierkegaardian leap into faith, and the Camusian embrace of the absurd. This is not however the overt theatricalisation of Jennet or Beckett. This absurd instead plays out in the daily lives of everyday people, through illness, forced separations, death, and in the banality of repetitious daily life. Yes there are flourishes of theatricalisation apparent in the “International Assassin” episodes and in “It’s a Matt, Matt, Matt, Matt World”. But all in all the absurd in this series is expressed in a more intimate and personal fashion; for example in “Cairo” when Kevin wakes to discover he has abducted Patti, and this results in her taking her of own life. When he cannot stop her, we and he are faced with the absurd. When Laurie watches as the unborn child she doesn’t want disappears from her womb, she too is confronted with the absurd. It is the not knowing why, and the calling out to the universe for answers and being met with silence that defines this space.

All three dramas grapple with the absurd through the actions of each narratives’ characters’ attempts to make sense of their worlds and to put them to right. For Matthew Jamison the absurd is eluded in the pursuit of false hopes and miraculous salvation. For Elliot elusion resides in the belief that his hacktivist actions might miraculously solve the problems of the world, when in reality he only replaced one set of problems with another. And for Cooper, the act of philosophical suicide resides in his belief that he could make the world new again by undoing what could not be undone. This is of course not a capitulation to the nihilistic. It is instead the recognition that the world and life do not always make sense, and that the process of sense making is itself ongoing.

As I stated in the introduction to this article, there are commonalities of theme, ideas and realisation that link Twin Peaks, Mr Robot and The Leftovers together. In the following articles I will explore these links further, examining the strange realities these narratives occupy, along with the fluid and symbolic spaces, objects, things, and places that inhabit these apocalyptic and revelatory works.

Notes

[1] It is also worth mentioning that I could have included Fargo and the OA into this grouping however I would rather take a different pathway in discussing these works utilising a purer existential and absurdist approach in the case of Fargo and a more gnostic approach to the OA.

[2] Talk House Podcasts, Sam Esmail (Mr. Robot) with Mark Frost (Twin Peaks), podcast audio, Talkhouse Podcast, 48:422017, https://www.talkhouse.com/sam-esmail-mr-robot-talks-mark-frost-twin-peaks-talkhouse-podcast/. Jeff Jensen and Darren Franich, A Twin Peaks Podcast: A Podcast About Twin Peaks. , podcast audio, Ep. 4: Helloooooooo, Damon Lindelöf! , accessed 13/06/2018, 2017, http://feeds.feedburner.com/twin-peaks-podcast.

[3] Simon Baré, Josh Lami, and Ali Sciarrabba to Black Lodge/White Lodge, July 4, 2018, https://25yearslatersite.com/2018/07/04/cancelled-catharsis-is-the-fire-walk-with-me-ending-invalidated-by-the-season-3-ending/.

Bibliography

Baré, Simon. “This Is Me, My House (Negotiating Meaning Amidst the Betwixt and between of an Absurd Existence).” University of Sydney, 2016.

Baré, Simon, Josh Lami, and Ali Sciarrabba. “Cancelled Catharsis?: Is the Fire Walk with Me Ending Invalidated by the Season 3 Ending?” In Black Lodge/White Lodge, edited by John Bernardy. 25yearslatersite.com: Twenty Five Years Later Site, 2018.

The Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, England.

Frost, Mark. The Secret History of Twin Peaks. Frist ed. London, UK: Pan Macmillan, 2016.

Frost, Mark The Final Dossier: A Novel. First ed. London, UK: Pan Macmillan, 2017. Novel.

Jensen, Jeff, and Darren Franich. A Twin Peaks Podcast: A Podcast About Twin Peaks. Podcast audio. Ep. 4: Helloooooooo, Damon Lindelöf! . Accessed 13/06/2018, 2017. http://feeds.feedburner.com/twin-peaks-podcast.

Saporito, Jeff. “In the First Season of “the Leftovers,” What Is the Significance of the Deer.” Screen Prisim, October 5 2015.

Oplev, Niels Arden. . “Eps1.0_Hellofriend.Mov.” In Mr Robot edited by Sam Esmail, 65 min. USA Network: NBC universal Television Distribution 2015.

Weinstock, Jeffrey Andrew. “Wondrous and Strange: The Matter of Twin Peaks.” Chap. 1 In Return to Twin Peaks: New Approaches to Materiality, Theory, and Genre on Television, edited by Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock and Catherine Spooner, 29-46. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2016.