In religion man has in view himself alone, or, in regarding himself as the object of God, as the end of the divine activity, he is an object to himself, his own end and aim. The mystery of the incarnation is the mystery of the love of God to man, and the mystery of the love of God to man is the love of man to himself. God suffers—suffers for me—this is the highest self-enjoyment, the highest self-certainty of human feeling.

– Ludwig Feuerbach, The Essence of Christianity (1841)

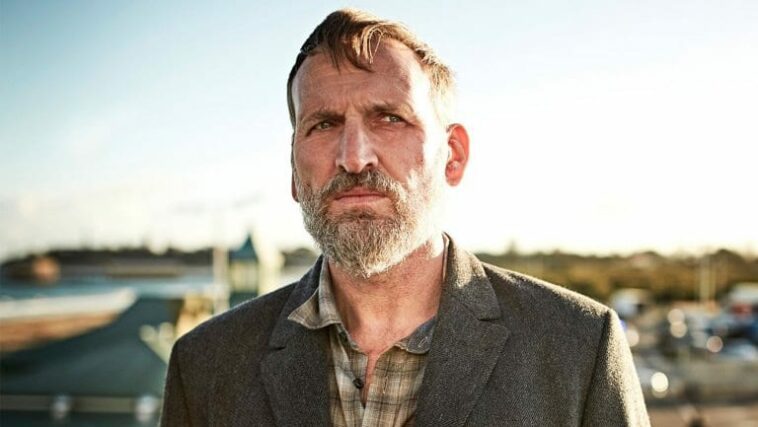

Matt Jamison believes — as he tells his sister Nora — that the Departure is a test, not in relation to what came before, but in terms of how human beings respond after. It was not the Rapture, as those who departed were not necessarily good people. Christianity is thus as relevant as it ever has been, if not more so. That God was responsible for the events of October 14th seems obvious to this man of faith, which is why he is so strident about making the sins of the departed known. It is not a matter of them being punished, but it even more certainly is not a matter of them being rewarded. It is a test: how does one respond to the mystery? Of course, Nora thinks that if that’s right then Matt might be failing. He does basically harass people with those flyers, after all.

Matt is fundamentally a man who has faith in the face of the absurd. The episodes that center on him share a common theme, or question, in this regard. Will Matt’s faith be rewarded? Is he “right” to believe? He is, more or less, a Christian Job.

The Departure did not make Matt lose faith — as it seems to have for most of his congregation — even though this event directly led to his wife Mary’s condition. The driver of the car that hit them disappeared, and Mary ended up in a coma. But rather than reject God, Matt doubled down on his Christianity: this is a test.

On a trip to a casino to uncover dirt on one of the departed, Matt sees pigeons on a roulette table, which is weird. How did they get into the building? He had previously encountered one in his church, which is not as weird since churches tend to be less hermetically sealed than casinos. But Matt ultimately takes this as a sign after he discovers that he needs to come up with $130,000 or lose his church.

Interestingly, it is as he stares at the painting of Job on his wall that he seems to have his epiphany. Job suffered without justification — it was just some perverse bet between God and Satan, or so the story goes — but never lost his faith. He refused even to truly ask why these hardships were befalling him, despite the encouraging of his friends. Due to Job’s faith, and his silence in the face of God, the latter wins his bet, and Job has all he had lost restored to him, and more.

Perhaps the wager involved in Job’s story is a part of what inspires Matt to dig up money left in the Garvey yard for him by Kevin Garvey Sr. and head to the casino to bet on the roulette table where he had seen the pigeon; everything on red, three times. And it works! Is this Divine Providence?

Well, he proceeds to get robbed by a guy in the parking lot, but he chases that guy down and beats him up, smashing his head against the pavement. (There is no follow-up to answer such questions as: did Matt kill that guy?) So, the robbery seems to speak against providence, but Matt keeps the money, so maybe not?

Now all he needs to do is get to the bank on time, but he is held up along the way when he encounters a member of the Guilty Remnant who has been hit by a rock. Being a good Christian, of course Matt stops to help, only to be hit in the head by a rock himself and wind up in the hospital for several days. Thus, he misses the deadline to save his church, and discovers that the buyer was none other than the Guilty Remnant.

So were the pigeons in the casino a sign from God, or was it all just a coincidence? What is a sign, anyway, other than something that calls out for interpretation? That is, the sign grabs one as significant; it forces thought. One could easily view the pigeons as an insignificant annoyance — and surely many at the casino did just that — but perhaps things strike us as signs precisely due to a certain synchronicity. In this wonderful interview about the show, Matt Zoller Seitz tells Damon Lindelof about how he and an ex-girlfriend came across a fork in the middle of a hotel hallway shortly before they broke up. Put a fork in it. Or, here we have a literal fork in the road. Of course, they both recognize that what happened was that a fork fell off of a room-service cart, or something like that, but in the actual experience of life, an event like this plays as a sign.

This ambiguity exemplifies Matt’s story. We might want to insist that the pigeons either were or were not divine guidance, as if it’s a zero-sum game, but the point is that in actually living one never gets an answer to such a question. One must answer for oneself, respond for oneself: do you choose to believe, to deny, or to tarry with the absurd?

When the Jamisons move to Jarden, the first day they are there, Mary awakens from her coma for just that one night. Is this because of the place? Matt can’t help but think so, but we also see him engaging in the same routine day after day — the same song, the same burrito — in the hopes that it will happen again. Here he is like the woman in her wedding dress, or Jerry the goat killer; this is not Christianity, but superstition. And yet, can we blame him?

All of this shows Matt’s discipline and his level of devotion to his wife — both of which are not only impressive, but endearing — and yet it also shows him stepping down the path of thinking that Jarden truly is a miraculous place. When he discovers that Mary is pregnant, he immediately believes that she has to be there in order to carry the baby to term. After she wakes up, he won’t let her leave town out of fear that she will relapse, and this destroys their marriage. As the seventh anniversary of the Departure approaches, he contends that it is in Jarden that something important will happen, pulling on all of the biblical sevens he can muster. He comes to believe not that Kevin Garvey cannot die, but that he cannot die in Miracle. And, thus, when he discovers that his reluctant messiah has taken off for Australia and become stranded there due to international events, he puts together a mission to bring him back to Texas.

Matt thus moves from faith in the face of the mystery to an obsessiveness with regard to a certain style of resolving it. It’s been seven years, and just look at all of the times that number is a significant period of time in the Bible. Kevin has died and come back, like Jesus, or maybe like Lazarus. Matt doesn’t claim to know what it all means, or where it is all going, but he has become sure that it is going somewhere, and that Kevin and Jarden are central to that story.

In fairness, he has evidence. Kevin has been resurrected, by whatever means. Mary did become pregnant even though she was previously infertile, and awake from her coma. But the song remains the same. Maybe the latter was just a coincidence? The former is harder to deny, given everything that we see in the show, but there is certainly a lot of interpretive space when it comes to thinking about what it means. At the very least, given what Virgil tells him about fighting his own adversary, it’s not clear that this is limited to Kevin. An old pederast may well have been able to do it, too.

All of this makes the end of Matt’s arc incredibly intriguing. He travels to the other side of the world to bring Kevin home, only to find himself on a boat with a sex cult devoted to Frasier the Sensuous Lion. There, he finds himself very offended to learn that a man named David Burton has been calling himself God.

By all accounts, Burton has also died and come back, and it is worth noting that Kevin interacts with him multiple times when he moves to whatever the place is beyond the veil. But Matt does not know this. All that he knows is that this man is claiming to be God, and, what’s worse, won’t even talk to him. He simply hands Matt a card that responds to frequently asked questions.

It is true that Matt then sees Burton push someone off of the boat, but it is worth asking to what extent Matt is truly driven by a notion of justice in relation to this murder, and to what extent it is by the fact that God won’t talk to him. He is too busy reading “Lonely on the Mountain” by Louis L’Amour.

Matt’s character does not just play in analogy with Job for the viewer; it is clear that he himself conceives of himself in relation to this biblical figure. This would seem to be at play, for instance, when he takes over for the man in the pillory outside Jarden. But unlike Job, Matt cannot stay silent when God appears to him. He ties him to a wheelchair and pushes him for answers.

Burton denies paternity of Jesus (“Mary’s word versus mine”), says that he died and rotted in the cave (everyone mistook his identical twin brother for him a few days later, you see), and refuses to take responsibility for anything Matt lists besides the Sudden Departure. When Matt presses him to tell him why he did that one, all God says is, “because I could.” Matt insists that there must be a reason, saying that there is a reason for everything he has done in life, while God continues to just ask him “why” until Matt erupts in anger and says, “for you!”

Whether or not David Burton is God — whatever that would mean — it becomes clear that Matt takes him to be a stand-in. I don’t think he intended this to happen. In all likelihood, he grabbed Burton to try to get him to confess to throwing someone overboard, but also to prove that he was not God as he claimed. Matt is employing the Socratic method, but unlike the interlocutors in Plato’s dialogues — who often respond insipidly by saying things like “of course” — Burton pushes back. He may not be God, but he refuses to drop the act or accept anything as a contradiction. He is playing the role not of a rational and loving God, but of one defined by power, authority, and even caprice. He’s the God of Job, making a wager for no good reason, but just because he could.

But unlike Job, Matt cannot help but question his lot. He begs to know why his cancer has returned. Is it because, as Burton has just told him, he was motivated by the notion of a God standing in judgment, and thus, at the end of the day, selfishly? God does not respond, but Burton says he can save Matt again, if only he unties him. And so he does. Burton reaches towards his face as if to cup it lovingly, snaps his fingers in front of it, and says, “Ta-da!”

Then he gets eaten by a lion.

Is David Burton God? The scenes he has with Kevin in the “other place” certainly complicate the question, but it also seems like a mistake to focus on it in a metaphysical register, as if there were going to be some way to answer that.

The important thing here is Matt Jamison. He shifts from decrying Burton as a charlatan to talking to him as though he were God. It’s not for nothing that the music kicks in. Matt had chosen to believe in the face of the absurd. God has a plan. Everything happens for a reason. Kevin Garvey died, and yet he lives. And here is a man for whom, by all accounts, the same is true: David Burton. And he’s an asshole.

What if God is an asshole?

This is the question that Matt is led to ponder. It is not that he ceases to believe in God. The Departure happened, after all, and what other explanation could there be? But there is a difference between belief and faith. If God is perhaps irrational, whimsical, and unloving, how could one keep faith with that?

Matt’s parents died in a fire. He had cancer as a child, and now it is back. His sister Nora lost her whole family on October 14th. His wife was left in a coma after a driver disappeared from a car and blindsided them. It’s no wonder that Matt identifies with Job.

We suffer senselessly. Parents die when their children are still young, or lose those young children. Try and tell someone who has experienced this that it happened for a reason. It may work as a consoling cliché, but you’ll be consoling yourself, not them; to take it seriously is nigh offensive. The Departure may be a grand metaphysical exemplar of the senselessness we encounter in life, but it is just that: an exemplar of the absurd.

Matt Jamison is heroic in the face of this absurdity. He holds to the notion that it all makes sense in some metaphysical way. That’s faith. Call it faith in God — however you think about God — because no other term is appropriate. It’s the faith that, in the last instance, things do, or will, make sense.

And to see that faith break is a bit heart-wrenching, even for someone who has never shared it himself. Matt gives up his whole thing with Kevin and goes with Nora. It’s clear that he no longer has the faith that he once did, but he does have love for his sister. And maybe love is enough.

“It is not an if faith you must have but a though faith”-MLK. Faith is not a bargaining tool. The other thing to mention is that Job was not a man who walked with God and as such used God to have his good life. It was only after the suffering unleashed by the “accuse” (not Satan) that Job was gifted, not rewarded with the plenty of God.

That is so literally, deeply besides the point that was suggested here. You are getting into an applied narrative onto a historical document and speaking

As though that narrative holds the same authority as the document itself. As though this can’t be considered in a far more objective sense.