Annihilation’s Area X functions like a prism. The ‘light’ (or matter, I suppose) of the rest of the world is refracted through the Shimmer that borders the region and comes together in new ways, changing the molecular makeup of each living creature in the area. It modifies everything, right down to brain chemistry, driving people insane as they are separated from their previous conception of themselves. The most obvious and directly frightening version of this in Annihilation is the bear, which attacks the group, and has been blended with the consciousness and parts of the body of Cass Sheppard, who it attacked earlier in the film.

“Help…me…” it groans, in a distorted version of her voice, forcing the others to realise that the horrifying creature attacking them is composed of the remains of their friend. It’s a horrible scene—the face of the bear is gruesome, and its skull is clearly visible underneath the skin as it groans its pain.

This is just one of many examples of how the world is refracted through the Shimmer, untethering each living thing from itself. My favourite, however, is Gina Rodriguez’s Anya staring at her arm as she can see something wriggling underneath her skin, as the others discuss the theory of the changes wrought by Area X. She is being changed right there, and keeps quiet about it, because what else can she do? Her transformation isn’t physical, but rather mental and emotional. Over the course of the film, she goes from a bubbly, flirty professional, to eventually tying up the rest of her team because she’s convinced they’re going to betray her. It doesn’t matter that there is no-one who they can betray her to because Anya is just convinced that they will. The paranoia and confusion set inside her brain and it untethered her from her reality. And this was achieved through making her suspicious of her own body. Her self-imposed isolation is what disturbs the most by her transformation—creating an inverted image of the outgoing and friendly woman she was at the start of the film, inviting Lena to eat with the others and trying to integrate her into their group. Garland uses the scene to expand on a recurrent idea in his work; that of the near-impossibility of understanding one’s self in isolation.

It’s visible in Never Let Me Go, where the overarching metaphor is that the soul is visible through interactions with others. I doubt that any viewer of that film would emerge with the opinion that Kathy and Tommy were the soulless shells that the other characters pretend they are. They insist on their love for each other, and who are we to deny them that dignity? Annihilation, appropriately, presents its inversion through Anya—she cannot confide in others, so the changes she undergoes aren’t just physical, but rather mental. Paranoia breeds isolation, and isolation exacerbates the paranoia. Any insights gleaned in isolation are corrupted, and the closest the team of scientists come to understanding Area X is when they talk it through as a group, relying on each other’s knowledge to fill in the blanks.

The climax of Annihilation is extraordinary. It is a slow, literal dance between Natalie Portman and the humanoid creature in the Lighthouse that gradually morphs into Portman as it goes on. Portman’s Lena starts by resisting the creature, fighting against it before being drawn into a dance with it, where it mirrors her every movement. The fact that they end up looking identical is almost besides the point—they were acting in tandem long before that. The sounds of this scene aren’t that of dialogue, just the score by Ben Salisbury, with every other sound and cry deadened by its synthetic twangs. The sound design alone feels unnatural and uncanny. It’s as though it’s silent, despite our constant awareness of the score. When watching it, I strain to hear Natalie Portman’s movements or her crying out in pain or surprise, but there’s nothing, and that makes the whole thing feel wrong. Which is, of course, the emotion we are meant to feel at that moment.

The lack of dialogue emphasises not only the visual importance of the scene but also its unknowability. Lena cannot articulate the experience, and we shouldn’t try to either. The way that Lena’s double mirrors her movements (not ‘mimics’, and that’s important. They move as though their bodies are responding to the same consciousness) only adds to the uncanniness. We think of ourselves as individuals, and this scene undermines that. Lena (and her book counterpart, The Biologist) thinks of herself as an isolated person, independently-minded to the point of not even wanting anyone around to disturb her thoughts. It prevents her from forming relationships and, crucially, it prevents trust. To be thrust into a circumstance where it is irrefutably proved that she is not, in fact, alone in any way (not even within her own thoughts) is an irony, indeed. It goes back to the idea of Annihilation being concerned with mirrors and inversions. But most of all, it undermines the very concept of the self. Her husband’s double is the one to return from Area X, and it is ambiguous as to whether the same applies to Lena herself. There is no point, Garland implies, in having a sense of self that relies on any form of ‘uniqueness’ or originality. You cannot exist as an isolated, fully-formed being without the intervention and influence of others.

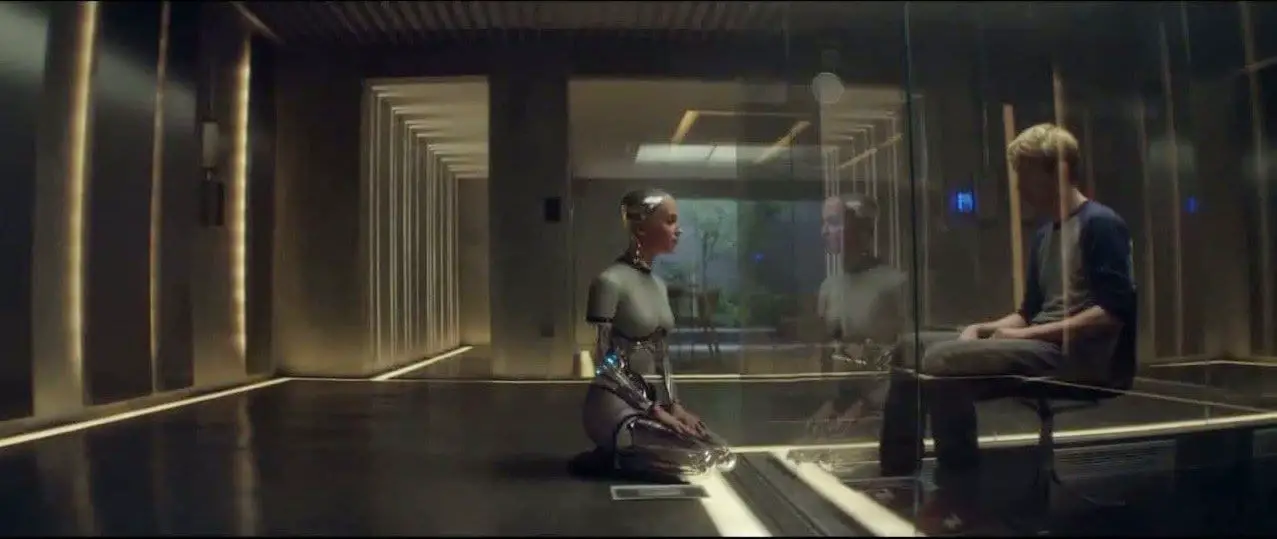

This is a question that is more fully explored in Ex Machina. Caleb is shocked to discover that Nathan took Ava’s appearance from his sexual and porn preferences. She is slim, doe-eyed and pretty because she is literally tailored to be attractive for Caleb. He, obviously, is horrified at the invasion of his privacy (not at her being made as a literal sexual fantasy for him, of course), and therefore considers her an amalgam of other women. The core problem in assessing the authenticity of Ava is her lack of ‘uniqueness’. Physically, she looks like the search results of Caleb’s incognito browsing history, and mentally she is a literal product—designed and perfected by Nathan over years of obsessive work. How, then, can she be said to be an original, authentic artificial intelligence, when even the name of it contains a concept that belies her sentience: ‘artificial’. Nevertheless, as I have stated previously, it’s made obvious by the climax of the film that she possesses sentience.

She takes a sensuous enjoyment of nature, feels righteous anger towards the men who imprisoned her and is able to recognise and manipulate Caleb’s sexual attraction towards her. An amalgam of traits designed by, and for, men she might be, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t worthy of being treated as a person. Through Ava, Garland undermines not only the idea that the self is something developed by an individual but the very idea of originality in the first place. We are all products of previous generations, visible through our genetics and family resemblances, and the contexts in which we have been raised. Ava might not be human, but her development into a being worthy of dignity and respect is not actually that far removed from our own, despite the science fiction trappings.

The self is, according to Garland, not defined by any claims to originality. In his films, there is a recognition that the self can only be understood through interactions with others. Lena defines herself as rational, and thoughtful, but she is then presented with a mirror image of herself that cannot be reasoned with or out-thought. Instead, her double is pure physicality, in direct contrast to the ever-questioning scientific mind of Lena. Area X inverts the characters’ perceptions of themselves, in a refractive process that upends any prior understanding of themselves. Likewise, the very existence of Ava discombobulates Caleb and Nathan, as they are utterly incapable of seeing through her manipulations, and instead perceive her as a simple composite of that which created her. A unique self is not the source of human feeling or the idea of humanity itself—it can always be imitated and manipulated and repurposed. Instead, Garland figures the self as something that is ever-changing. Biologically speaking, our cells are constantly in a process of dying and being created, so it seems reasonable that our idea of the self also undergoes that same process. It is contextual, reliant on circumstance and myriad influences that cannot be summarised by saying “She is out-going” or “She is clever”. Alex Garland understands that the definition of humanity is not, and will never be, as easy as that.