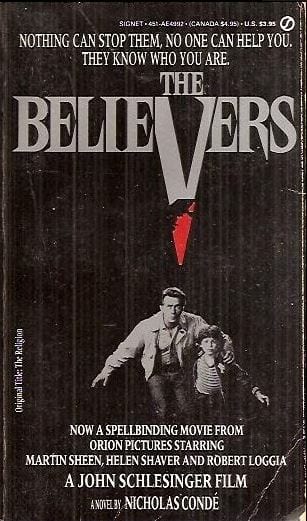

In perfect time for the Halloween season, we are finally looking at Mark Frost’s screenplay for John Schlesinger’s 1987 film, The Believers. IMDb summarizes the plot as: “A New York psychiatrist finds that a brujería-inspired cult, which believes in child sacrifice, has a keen interest in his own son.”[1] Succinct as that summary is, there is a lot to unpack about this film and some of the decisions Frost must have encountered in writing the screenplay. First, the film is based on Nicholas Condé’s 1982 novel, The Religion, a work, it seems to me, right out of horror’s 1970s and 80s paperback history as compiled by Grady Hendrix in last year’s Paperback from Hell. That is where I began looking for information and history on the original novel, anyhow.

Consulting Hendrix’s book, I couldn’t find any mention of Condé or his novel but was then able to reference the blog that inspired Hendrix, Too Much Horror Fiction by Will Errickson, and was able to find an entry. Errickson’s reading provides us a decent reception of the novel to begin noting some of Frost’s tasks in adapting the screenplay. “Early on I liked the academic anthropology angle, but making ‘the religion’ an actual one – Santeria, a voodoo variant – showed little imagination and a weird sort of tasteless cultural appropriation. I think if Condé had created a bizarre cult of his own, I’d have been much more into The Religion, but I guess I’m just a horror fiction atheist after all.”[2] Residues of awkwardness from the cultural appropriation, as Errickson reads it, remain in the film, but those instances do not discount what is a solid and smart thriller, given its origins. I reiterate that the awkwardness remains but not the intention. Nicholas Condé’s novel was initially released in hardback but was, of course, eventually relegated to those drug store mass market racks where horror always managed to reach the masses best, in a form meant to be read and trashed. It would be the task of Mark Frost to turn that material into a Hollywood seller that could support talents the likes of Martin Sheen and Robert Loggia.

An interesting fact is that Nicholas Condé is actually a pen name for a collaboration between two authors. Their Amazon biography tells us more. “Nicholas Condé is the pseudonym of Robert Rosenblum writing with Robert Nathan, who has been prominent in writing for Law and Order TV series … The other Condé novels also involve exploration of spiritual worlds in collision with the modern world.”[3] Those familiar with Frost’s interests can understand how he found this material engaging. As he states in an article for Ojai Quarterly, “’My interest in Krishnamurti and Theosophy dates to the ‘70s, under the category of ‘spiritual curiosity’ for a young adult who was decidedly non-religious by nature and nurture,’ Frost says.”[4] With their 1982 novel, Rosenblum and Nathan (Condé) place Cal and his son in New York City after the death of their beloved wife and mother, Laurie, at their previous home of New Mexico. Fresh from the tragedy, Cal and Chris are in for more than culture shock in the Big Apple. They are up for a test of their religious beliefs, or lack of, against the white magic of Santería and black magic of Bujería. This is the set-up in the film, anyhow, taking from the novel’s notions with its current e-book subtitle “The Great Classic Novel of Urban Voodoo.”

The novel picks up specifically in Central Park New York, where young Chris Jamison cheers his discovery of an “arrowhead.” Cal cannot help but encourage his excitement. “’The Mohawks came through New York on their way north,’ Cal said. ‘And the Senecas.’ […]Let him believe Cal thought. The flash of enthusiasm Chris had shown at the discovery of his ‘arrowhead’ was all too rare these days.”[5] As we learn about the characters, we’re fed the background on Laurie little by little. Mark Frost, instead, chose to pick up the story by front-loading Laurie’s tragedy as a prologue. It is morning time, and Chris plays at the breakfast table with his African tribal doll. In the novel, Cal is an anthropology professor who taught at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. In Frost’s adaptation, Cal is given a little more separation from the on-the-nose profession and is a psychologist instead. This allows for more credibility to his later work with Lieutenant Sean McTaggert regarding ritualistic murders around the city and his psychological review of Jimmy Smits’s Tom Lopez. Still, that Cal is a psychologist in the film might confuse Chris’s strange choice of toy at the beginning of the film, a tribal-looking figurine, except that in Frost’s version Laurie is the prized pupil of famous anthropologist, Kate Maslow, who we will return to shortly.

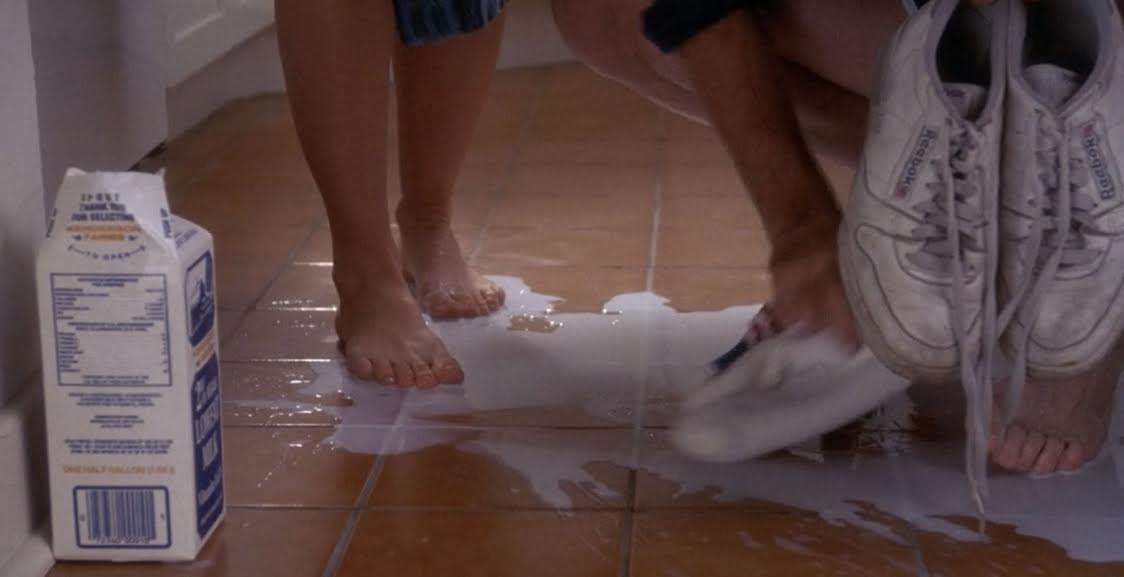

Frost’s opening begins with Cal having his morning jog as he’s trailed by a milk delivery truck. As mentioned above, Laurie is at home making breakfast as Chris plays with his tribal figurine. We see the coffee pot is placed oddly on its hotplate so that coffee dribbles down into the undercarriage of the machine unnoticed. Cal enters the kitchen, cheerfully joking with his family when Laurie spills the delivered carton of milk. They each step into it in an attempt to clean up the puddle. It is white and wholesome, but who says you can’t cry over spilled milk? Cal gets in the shower while Laurie continues to clean the mess when Chris gasps, pointing at the malfunctioning coffee machine. Steam rises from the pot. As Laurie reaches fast to turn it off, we realize that she is still standing in the milk when she is electrocuted. As the novel tells us, “Then suddenly it was over, Laurie’s life ended by what the insurance companies listed on their actuarial tables as the ‘leading cause of death’ and called simply ‘an accident in the home.’”[6] In the novel, her demise is by a defective toaster Cal neglected to throw away. This is our first instance of Frost improving on the original material as I show below.

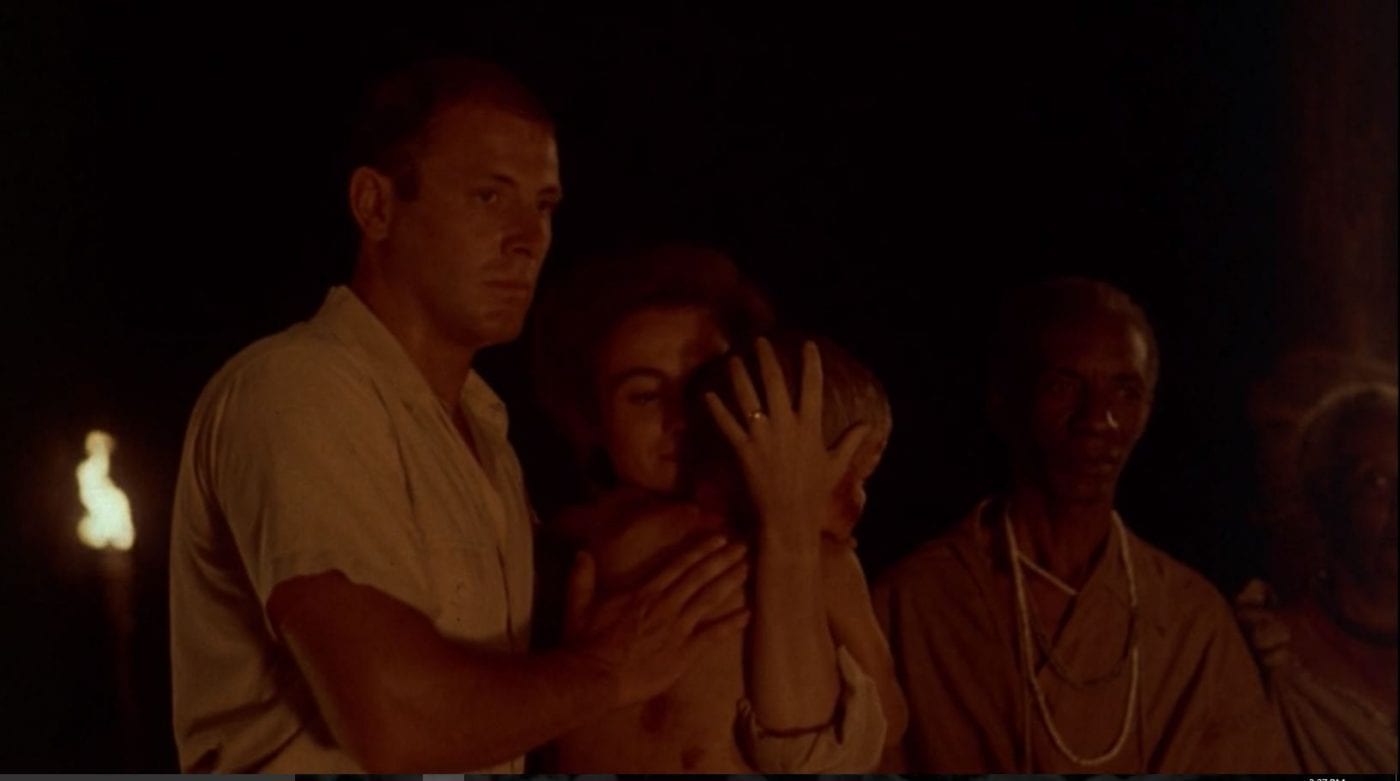

The white of the milk (white magic, Santería), the black of the coffee (black magic, Brujería), each represent substances that when mixed together result in dangerous and deathly outcomes. Maybe Mark Frost had his opinion on keeping coffee “black as midnight on a moonless night” a couple years before collaborating with David Lynch on Twin Peaks after all. Of course, that’s doubtful but fun to note. Regardless, it sets up the struggle between the two practices at the onset. Following the tragedy, the credits portray an exotic dancing ritual that is either an African or Caribbean healing ceremony, perhaps not mutually exclusive. Two parents are seemingly giving their ill child over to be healed in the exotic ritual. The audience would not likely know the details to properly separate the cultural origins of the portrayed rituals—I did not—and this takes us back to Errickson’s statement on the novel, that the dangers here are from “a weird sort of tasteless cultural appropriation.” So, without playing the expert, I’ve reached for some sources that might give a little more guidance, some education, on the belief systems that are shown as the magicks and horrors in this novel.

One point I might note is that this film would be followed up by another famous horror film on voodoo, Wes Craven’s The Serpent and the Rainbow (1988) as adapted from Wade Davis’s questionable research on voodoo and zombies published with the same title in 1985. That work seems to reflect some of the confused views of the religions or practices of the time, a time when cultural appropriation may not have quite had a terminology yet, regardless of how one reads it today. Still, Grady Hendrix, speaking to horror novels of that era, informs us plainly that “[i]n horror fiction, every culture has its own supernatural menace. African Americans get voodoo. The Chinese get fox spirits. And WASPs (white Anglo-Saxon Protestants) get the all-American boy sporting a varsity letter jacket and blinding-white smile that mask the howling maniac on the inside.”[7] We seem to be in the territory of the first group with this film, but the voodoo the African American characters get is the caricature of voudon laid out by Benjamin Radford in his write-up titled “Voodoo: Facts About Misunderstood Religion.”

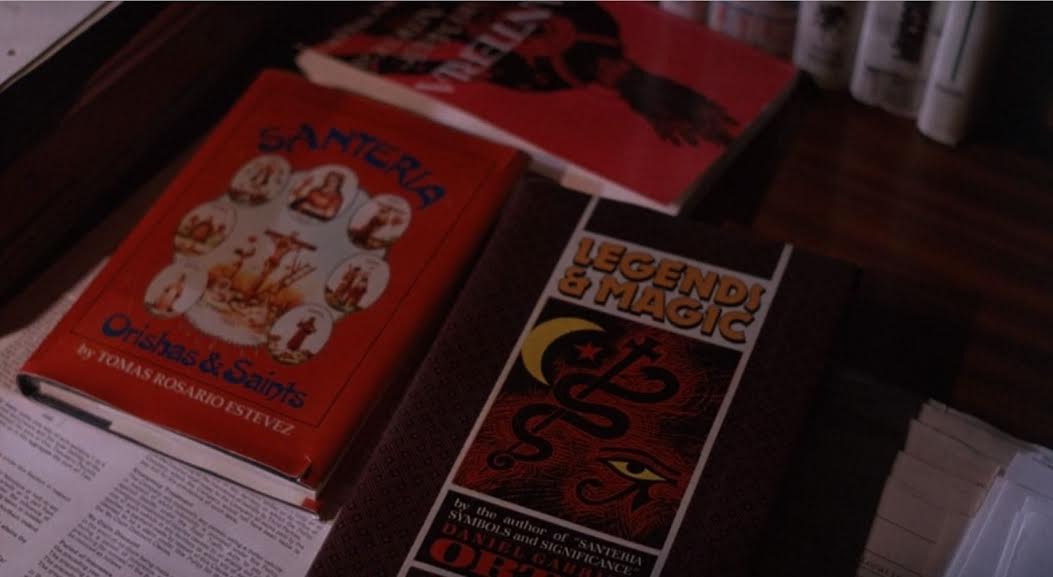

As he explains, “Voodoo is a sensationalized pop-culture caricature of voudon, an Afro-Caribbean religion that originated in Haiti, though followers can be found in Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, the United States and elsewhere. It has very little to do with so-called voodoo dolls or zombies.”[8] Further, to give us a view on Santería, according to an entry in The Encyclopedia on Caribbean Religions, “Santería is one of the Cuban religious forms with a polytheist orientation of African, specifically Yorba, descent, deeply rooted in contemporary Cuban society and culture.”[9] Religious beliefs in this story seem to come from the African diaspora, meaning when African peoples and customs were spread through the slave trade. Santeria is said to mean “worship of the saints,” which hints at its Catholic ties as well. It is not hard to imagine as culture spread that to avoid persecutions, some early, pagan beliefs were disguised or incorporated into Catholicism simply as a necessary mechanism for survival of the people and the beliefs.

To cap off our understanding of the Brujería side, we can expand by referencing work by Raquel Romberg in an article titled “Sensing the Spirits: The Healing Dramas and Poetics of Brujería Rituals,” which “explores the sensuous spirituality of healing and magic rituals in Puerto Rican brujería (witch-healing).”[10]

[C]arefully crafted gestures, meticulously manipulated objects, poetically strung words, and spiritually inspired music and dance create an inter-temporal and inter-ritual, dramatic experience that is in itself healing. When the voices of Spiritist entities, Santeria orishas, and the recently dead become suddenly manifest during brujeria rituals, divination, trance and the making of magic works, their power is sensed, their immateriality embodied (see Csordas 1990, 1993). This is when the spirits reveal to the living the sources of affliction and their solutions in a totalizing, emotional event that involves all the senses, where the body and the mind, as well as otherworldly and this world causes, are treated in tandem; in sum, where healing begins.[11]

The sentiments in that explanation of Brujería rituals are the same as those perverted by the antagonists of The Religion and The Believers. Also, that description reminds us of the dancing ceremony we see in the film’s credits. So, where does it begin for the Jamisons? It begins back in the park in a scene found at minute ten of the film and in chapter one of the novel. The scene shows Cal’s anxiety at being the sole parent of his son in Laurie’s aftermath as he loses him in the park. When he finds him, Chris is deeply interested in a crime scene, one of ritual animal mutilation in the middle of the park and where he finds his curio, his “wishing shell.”

Here begins perhaps some spoilers and where I will try to tie up the material for sake of space. Forgive some heavy quoting, though it makes its point. At a dinner later with Laurie’s mentor Kate Maslow, Kathryn Clay in the novel, Chris shows off his wishing stone to her and her husband. The anthropologists admire it, assuring Chris of his good find. It is described in the novel.

It was not the shallow flattish type from a bivalve, but a fragment of the swirled conical variety. The outer surface was etched with a row of angular markings. At first glance Cal had thought the shell was broken, but with closer examination he saw that the outer lip had been filed away, neatly baring an interior section of the shell’s serrated edges so that it resembled a tiny mouth with opposing rows of minuscule teeth.[12]

Here, we should also note a finding of Errickson’s. “But there are no surprises anywhere, not in characterization or plot development (well, one character seems based on Margaret Mead, which made for some decent reading).” Maslow/Clay is our Margaret Mead, a description not thinly veiled in the novel. “She had been an outspoken feminist before Jane Fonda was in grade school. She had campaigned for birth control and the sexual rights of women long before either cause became fashionable. And she had been through four husbands, all older than herself—a literary critic, the famous anthropologist Quentin Kimball, a university president, and a shoe manufacturer.”[13] It’s a point that reminds me of Frost’s good decision in giving Cal some separation from the anthropological aspect of the narrative. Cal’s housekeeper, Carmen Ruiz, witnesses a crime scene on her way home, one where a sacrificing ritual has been performed and where a disturbed Tom Lopez as portrayed by Jimmy Smitts bemoans that the perpetrators have his name badge; they know his name. Carmen brings the white magic of Santería rituals into the Jamison’s household, sensing the danger Chris is in.

For the film’s purposes, Robert Loggia’s Lt. Sean McTaggert calls in the psychological services of Cal to check in on seemingly suicidal Tony. This is where Cal is brought into the bigger picture of the underground, ritualistic forces. Of course, there is the research scene wherein her gathers books on the subject a danger for any horror protagonist, be their knowledge from grimoire, books, or newspaper microfilm and microfiche. At the same time a mysterious African man with cloudy eyes appears in town, unpacking his ritualistic accoutrements in a nondescript hotel room. Then, as paperback horror would have it, the curses begin—belly snakes, spider-filled zits, an affluent cabal, and unlikely alliances who use the powers of Santería to battle back the evils of the African witchcraft of Brujería.

As the cabal are revealed to Cal, of course Kate and her husband, both well-traveled anthropologists, were the couple in the credits the entire time, offering their sick child not to be healed but to be sacrificed. Now the wishing shell has marked Chris, and Cal—the parent has to do it—will be lulled into sacrificing his son. So, let’s turn back to the book for a last notion here. It is in an early passage of the novel, where Cal pulls out a book he packed in New Mexico, a copy of Old Testament Stories for Children, that Laurie must have bought to give Chris some education on beliefs. Cal reads from it to Chris one evening, when he realizes which Abraham story they are treading.

Cal hesitated another moment. As usual, he had started reading at the place he’d left off last time. He had gone unthinkingly through several paragraphs before realizing exactly which Old Testament tale was unfolding. Then he wanted to stop. Hearing this story would be no good for Chris; he was already in a vulnerable state, questioning the permanence of relationships. The fable of a man asked by God to kill his own son was the stuff of nightmares. […] Cal read it to the end. The voice of God spoke to Abraham, commanded him to spare his son; and then Abraham saw the ram tangled in the thicket, and the animal was sacrificed instead.[14]

Cal’s choice to either offer his child to the evils of the voodoo cult, gaining himself prosperity and influence or overcome their temptations mirrors the story of Abraham. To the authors of The Religion, the decision to sacrifice for the Christian God is no less horrific than to sacrifice a child to any god. One would have to be possessed to do so, and Cal is in the novel, whereas he is drugged in the film. Mark Frost chooses to leave that much out of this particular thriller, but for the sake of exploration, I think it adds to our understanding of the film’s climax.

The wider narrative is one of belief. One part is the recognition of the cultures around us. I truly believe that the authors behind Nicholas Condé believed they were sharing not only an entertaining thriller but a look behind the curtain of New York’s diverse boroughs, and Mark Frost simply reworked the best notions of the novel into a story with a little less musing, a little more forward momentum, and added a neat trick in including sleight-of-hand magic as an equal foil to the evils in this story as if to say, it’s all hocus-pocus in the end. Though as Cal and Chris escape back to the safety of New Mexico with Jessica Halliday (again, see spider-filled zit) in tow, we realize that superstition breeds superstition. Non-belief may be safer than belief. Overall, we’ve got a B novel with an A movie made all the better by everyone’s involvement. It continues to feel like an 80’s movie, but that is almost a compliment anymore—the attitude, the statements on the pursuit and enactment of decadence, an attempt to understand minority cultures and the misunderstood richness of their belief systems. And if the voodoo horrors of The Believers or The Serpent and the Rainbow prove too much, there is always Weekend at Bernie’s II.

[1] IMDB. “The Believers (1987).” Accessed October 17, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0092632/?ref_=fn_al_tt_1

[2] Errickson, Will. “The Religion by Nicholas Condé (1982): I Am a Cliché.” Too Much Horror Fiction (June 5, 2012). Accessed October 15, 2018. Retrieved from https://toomuchhorrorfiction.blogspot.com/2012/06/religion-by-nicholas-conde-1982-i-am.html

[3] Amazon. “About Nicholas Condé.” Accessed October 15, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.com/Nicholas-Cond%C3%A9/e/B001HCZRB2/ref=dbs_p_ebk_rwt_abau

[4] Bradigan, Bret. “The Storyteller.” Ojai Quarterly (March 21, 2016). Accessed October 22/2018. Retrieved from http://theojai.net/the-storyteller/

[5] Condé, Nicholas. The Religion, (Robert S. Nathan and Robert Rosenblum, c2012; Condé, c1982), Ch. 1, loc. 111.

[6] Condé, Nicholas. Ch. 1, e-book, loc. 63.

[7] Hendrix, Grady. Paperbacks from Hell: The Twisted History of ‘70s and ‘80s Horror Fiction, (Philadelphia: Quirk Books, 2017), p. 65.

[8] Radford, Benjamin. “Voodoo: Facts About Misunderstood Religion.” Live Science (October 30, 2013). Accessed October 22, 2018. Retrieved from: https://www.livescience.com/40803-voodoo-facts.html

[9] “Santería.” In The Encyclopedia of Caribbean Religions: Volume 1: A-L; Volume 2: M-Z, 916. Urbana; Chicago; Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

[10] Romberg, Raquel. “Sensing the Spirits: The Healing Dramas and Poetics of Brujería Rituals.” Anthropologica 54, no. 2 (2012): 211-25.

[11] Romberg, 212.

[12] Condé, Nicholas. Ch. 3, e-book, loc. 382.

[13] Condé, Nicholas. Ch. 2, e-book, loc. 236.

[14] Condé, Nicholas. Ch. 3, e-book, loc. 436-447.