I am unsure how most people happen upon the movies of Richard Linklater. In all likelihood, the first film many will have watched, depending on what generation they belong to, would have been something like Dazed and Confused. A later generation would have enjoyed something fairly lightweight—School of Rock perhaps—and not really have taken much note of who directed it, much less sought out any of his work once they had easily digested that movie. I am afraid to say (but not in a bad way!) it probably spurned most to find another Jack Black comedy than to think that the man behind the camera had anything different up his sleeve.

And that is a shame. Admittedly, Linklater isn’t a David Lynch, a Ridley Scott or a Terry Gilliam. His visuals aren’t noted in awed art-heavy conversations, and his work doesn’t grab an audience in the way that, let’s say, a David Fincher or Martin Scorsese production would. He’s quietly directed 18 or so movies to date, most of which he scripted or co-scripted, and he has built a reputation for intelligently and surreptitiously focusing on society, individuals, and the brief but captivating moments that mix with the minutiae of everyday life. I remember reading Linklater say he didn’t make movies about a murder or gun fight etc. because he hadn’t experienced that—life itself is enough. “We don’t make films about the ordinary…Why make art about normality? We’re really conditioned, in films particularly, to have the big moments…Most of that stuff doesn’t happen…It’s not the big moments. They’re not the best.” [1] And that struck me as very true—that life can be dramatic enough without the need for additional turmoil or theatrical tragedy and heightened drama. A person’s journey through this life is drama in and of itself. It almost goes without saying that cinema can provide an escape, a much-needed diversion with triumph and closure when the credits roll; or a mesmerising banquet of visual and aural treats that delight the world-bleary senses and burn new, fantastic or haunting images into our memory; but it can also be thoughtful and thought-provoking, low-key, stealthy and affecting beyond the limits of running times. Richard Linklater seeks to capture that without fanfare, not just in terms of his cinematic style, but also the material content of his films.

For the purposes of writing about him and his work, it’s tough to make a decision on what exactly to write about (or should I say, where to start and where to end). But as his movies are often personal musings and meanderings on life—especially the films he has written and directed—I feel I should stick to that direction, both in terms of what output to look at, but also the content of my writing here. After all, these are the films he’s produced that probably mean the most to me—certainly the ones that have had the most impact in terms of challenging established and inertia-driven directions in my own thoughts and choices. That’s not to say that some of his other output doesn’t speak to his (or my) ideas and considerations in life such as A Scanner Darkly, Last Flag Flying or Fast Food Nation. These, and others, obviously represent threads of importance to him, from his political views through to his dedicated veganism, but I am going to sidestep them in the main. He’s been a prolific creator in the area of cinema but in being so, it’s hard to narrow focus without needing to write a book! And as I mentioned, because the following movies ‘appear’ so casual, so real and personal to him and the viewer, I want to look at them in the same way by examining my take on what they mean, how they volunteer their outlooks and the commonalities that make them (in my mind) so important.

So, in essence, I’m going to take a look at what I feel are the movies most unique to him and his story: Slacker, Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise, Waking Life, Before Sunset, Boyhood, and Before Midnight. And when I say that they are the most unique to him, it’s because of the connective motifs that I feel flow through them, commonalities in these artistic endeavours that—whilst subtly coursing through several of his other films—emerge as much more prevalent in the beating heart of those that he writes and directs himself. There’s going to be three parts to this series with this part acting as a recollection and general overview of those films I am looking at, with a little background on how I found them and what they initially meant to me. The second will look a little deeper at themes and readings of his work, whilst part three will look solely at what many believe to be his ‘magnum opus’, the Before Trilogy, in some personal and artistic detail.

“I’d like to stop thinking of the present as some minor, insignificant preamble to something else.” —Cynthia, Dazed and Confused

Backstory time. Linklater arrived at the end of the ’80s when the youth of the day had been captured by the wit and pop-wisdom of John Hughes; Spielberg’s domination of the rising multiplex culture alongside re-runs (and the return) of Star Trek; and low-budget sci-fi and fairly churned-out procedurals on TV. These mainstays gave me and many others solid, entertaining, schoolyard fan discussion material, defined in pretty limited mainstream-acceptable ways for the most part. In all honesty, I love Ferris Bueller and his day off, but luckily by the end of the ’80s and my late teenage years, the sarcastic, ironic and almost anti-Hughes Heathers appeared in 1989, and not long after, TV warped my mind with Twin Peaks. My limited worldview was fairly mundane and stereotypical in terms of what I had absorbed from the world of entertainment up until then. I was an easy target for comfortable distractions. I had moved from city to city with my family/father’s job, making new friends (losing old ones) and endeavouring to fit into whatever cliques existed in my new schools. I probably wanted stability, safety, fictional characters that were friends I had yet to make. But now (at the end of the ’80s) I was of college age and had an overdue need for my internal compass to be pulled in new directions for my still-developing sense of self and meaning (sounds pretentious? Definitely an accusation made about many a character in a Linklater film, so I am just fitting in nicely).

Linklater himself was 12 years ahead of me (around 29 years old) when, in 1990, he made Slacker. A self-educated writer/director, he had many small-time jobs when he left school, and the possibility of a career in baseball was sidelined by a heart condition (atrial fibrillation). A lengthy stint on an oil rig provided space to read aggressively and earn money to support himself outside of the career rat race he was to frown upon later, via his film material. Cinema dominated his time when he returned to Austin, Texas, and he consumed both mainstream and arthouse vehicles—tuning into the possibilities provided by the medium and what he believed American cinema wasn’t currently providing the upcoming generation or the reality of life around him that he thought wasn’t being shared at that time.

A year or more passed for me post-Peaks before I was once again moving across the country and, having freewheeled off the educational path following college (accompanied by a pervading depression), I happened to volunteer at a cable TV station near my new home (this was new tech in the UK at this point). Shortly thereafter, upon reading a singular and memorable review in Empire magazine about an unusual movie featuring a cast of a hundred, I managed to coax the cameraman (only a couple of years older than me) into giving me a lift to the new multiplex where they were having a one-off ‘Director’s Night’ of Slacker (after all, this movie was not considered a box office certainty, especially in the UK). My friend fell asleep, but I just about managed to watch this entire film play out, only to be left with a nagging sense that I simply didn’t know what that had all been about. I didn’t recognise these people—well, maybe a little—and they talked. A lot. About crazy, inane, intelligent, weird, political, cultural, pretentious, savvy, witty, and…well…just stuff. I had simply bobbed along and ‘hung out’ with them through a 24-hour period. No introductions, no context to speak of—just following a randomised collection of dropouts, college grads, would-be criminals, and preoccupied creatives on a bizarre yellow-brick road weaving through Austin, Texas. I woke my friend up and left the auditorium, wondering how that film had ever got made. I may also have had a headache.

Slacker, is in essence, 24 hours in the lives of residents of Austin, Texas, which mainly focuses on the younger generation. People of a pre/post-college age but also folk of a certain nature: dreamers, thinkers, non-mainstream, and on the fringe so to speak. Artists, philosophisers, would-be anarchists, band members and conspiracy theorists mingle throughout the 24 hours as we—the viewer—drift from one to another, listening in on both the grand schemes and day-to-day particularities of their lives. It captured a certain time in America, if not the world, where what had gone before (politically, socially, musically, artistically, and economically) was undergoing some challenge and change.

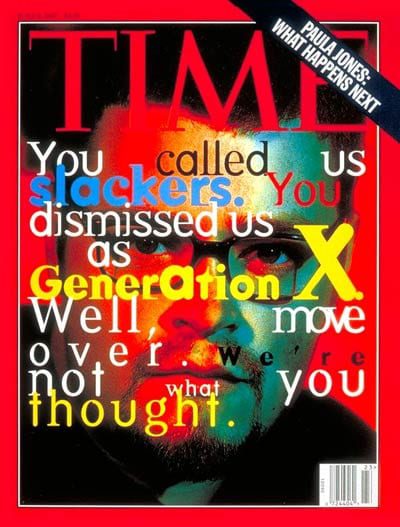

Many have commented that Slacker (and subsequent movies such as Dazed and Confused, the Before Sunrise/Sunset/Midnight trilogy etc.) captures the essence of what became termed as ‘Generation X’. Typically, the band Nirvana and Douglas Coupland’s book of the same name are dragged into the same context and usually in the same articles. Despite the overall reluctance of people in that generational bracket (I am firmly in that time frame too) to be labelled in any way, it does feel true to me. I can’t pretend, despite not wanting to be pigeonholed, that these books, movies and music did not speak to me in a way that many others produced before and since do not. But isn’t that what art can do? Capture a moment, an idea, an expression and engage with it on its own terms, exploring the creator’s mindset? If that creator is born and has been subject to growing up in similar circumstances as others of that time, can they then speak for, or at least speak to, others in both generalised and specific ways?

“Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.” —John Lennon

That’s what Linklater’s output began to do for me. It wasn’t obvious, to begin with, but as I followed his work cautiously and accidentally at times, I began to connect with the knowledge that here was someone who was exploring what it meant to have grown up in the ’70s and ’80s—but more importantly and accurately what it was like right then to be an adult, still growing, learning, resisting and acquiescing, and sometimes a shitstorm collision of all at once. But rather than throat-grabbing a viewer into an in-your-face partisan confrontation of inescapable truisms, Linklater’s chosen minimalist style encourages you to meander through ever-moving perceptions and truths, thoughtfully heading towards your own discoveries. This was in contravention to the movies of the time. The majority of the ’80s seemed to move past the experimental cinema of the ’70s into an arena dominated by the blockbuster—audiences sizes, popcorn sales and film lengths designed for maximum audience rotation. That’s an overly-generalising statement, but in my youth that is exactly what I was experiencing before my 20s, and the kindling of new thoughts not generated by school and peer pressures.

Slacker—the title—is a bit of a misnomer. The impression, if you take the dictionary definition as Gospel, is that it is (reductively) “A person who avoids work or effort.” [2] And if you look at the next but one entry, “North American: A young person (especially in the 1990s) of a subculture characterized by apathy and aimlessness.” [2] I’m left with a definite feeling this is the result of the movie. However, Linklater himself also disagrees with this assessment, as I do: “…we were using it affectionately…I guess it’s being misinterpreted. I was depicting people who were outside of the mainstream, who were sort of the underground. I didn’t see that as a negative. You look historically and these people are always portrayed negatively: beatniks, hippies, they’re ridiculed. Anyone who’s doing their own thing. It became a shorthand. It’s a film of 100 people, and they don’t work, and they don’t do anything. And my whole point was: No, they do a lot. A lot of people in the film, they’ve all got their projects, they’ve all got their activities. And I myself was one of them.” [3]

Slacker could be considered a difficult watch. Many have commented that they even fell asleep during the movie, but always found that the randomised philosophies and difficult lack of narrative structure beckoned them to return to it within days, to reevaluate and check out just what did that guy say to that girl about that JFK theory at that library? Why did that one sentence stay with me, and why did R.E.M. use it in the lyrics for ‘What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?’? Without that narrative anchor—and given that the time spent with each on-screen entity could either entertain (the infamous Madonna pap smear scene), intrigue (JFK assassination theories) or frustrate (“pasting bits…from your ‘authoritative sources’”) before moving onto the next haphazard meeting—it ironically requires a degree of attention from a viewer at odds with some of the messages the film seemingly delivers. But it’s never less than fascinating. For every subjective throwaway or meaningless scene, you only need to wait a short amount of time before you hit upon a line of dialogue or person of interest that resonates with you.

“Withdrawal in disgust is not the same thing as apathy.” —Slacker (And then quoted in “What’s The Frequency, Kenneth?”)

Generation X was apparently intelligent but apathetic, tired of consumerism and being a target market for our disposable incomes and avoidance of the old-school branding that our parents had enjoyed. Our music was raw, like punk had been, but with an astute knowing that belied the young age of the band members themselves. The cold war was finally over, and years of living in fear of nuclear destruction began to edge out of the western world’s consciousness (I remember being so scared, as TV used to dramatise what life would be like in a nuclear fallout). The yuppie was a successful prototype to be frowned upon, and it was just fine to take a low-paid job that enabled you to work on your personal creative outlets. Movies like Reality Bites, despite the occasional indie flourish, was one of the first signs that the entertainment industry clued in to this new cultural divide (before that, Generation X was simplified and reduced to the pejorative meaning of a slacker) and could attempt to target Generation X much like any other identifiable revenue stream. However, Richard Linklater was part of that target market, and he was not about to suggest that our lives were a commodity that could be pre-packaged and easily bought. He wanted us to think, to ask questions, and to engage in ways outside of the homogenised masses.

Following Slacker, and after a detour into his past with the more mainstream-acceptable Dazed and Confused (I will get to that shortly), he gave us Before Sunrise. A simple, yet intelligently complex, modern friendship/relationship amidst the realities of ‘the real world’ (actually, there was a series called just that on MTV. The reality TV genre was exploding at this point, and we were part of its agenda), the film captured the essence of a real event in Linklater’s own life, where he spent one night with a young woman wandering around Philadelphia (a fair way from the film’s setting of Vienna, where the European influence on his directorial style was becoming clearer to film historians and analysts). In the movie, American visitor Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and French-native Céline (Julie Delpy) meet on a train travelling across Europe. Their personalities click during the journey and together they alight in Vienna. There they spend the rest of their day (and night) together, wandering the labyrinthian city streets, baring their souls to each other by way of their histories, personal journeys, sincere trepidations and spirited aspirations, before Jesse departs back to the U.S. the following morning.

This was the next film in his output, following Slacker, that I caught at around 25 years old (and it had a bigger effect on me than I can actually recall here accurately). All I can say is that to discover that it was okay to connect with someone in such a profound way, to be attracted by/to their thoughts, dreams, aspirations, worries and frailties, as much as their outward beauty or simply whether you wanted to sleep with them…well…I guess at that time it wasn’t really my experience. Films didn’t portray that for my age group and without sounding in some way less than ‘a real man’ (whatever the hell that stereotype really means), I was encouraged that my ‘vulnerable’ side and my expanding anxieties and hopes were okay to have, much less express to someone I had genuine feelings for. And that they would be accepted—no, that they would be part of the attraction for someone else—was a brave and cinematically challenging subject to put into a film at that time. 1995. Batman Forever and Billy Madison, anyone? Linklater had found a compelling blend of intelligence, thoughtfulness and philosophising balanced with wit, humour and romance. The end to that film (I will discuss the Before Trilogy later, in part three) really intrigued me and made me feel both satisfied and optimistic that a relationship begun on such a foundation would endure. And damn, it needed a sequel.

The next film of his I watched (out of production sequence, but I seemed to have missed it) was a backtrack, both in time and in substance. If the two Linklater movies I had watched to date had pushed me into new realities of reflection, then Dazed and Confused brought me to a past I hadn’t undergone in the same way as its writer/director. It’s a particularly American experience of the last day of school/college in the late 1970s. Much like Slacker, we follow a variety of people through the night, but stay with core characters this time, following the riotous fun and considered ruminations on what this day means and what the future may hold.

Before punk and new-age arrived and at the height of the ‘baby boomer’ age and predating the economic boom years of the ’80s, the story of one night in Austin, Texas in 1976 seemed like a backwards step to me, but in fact was subject to my (admittedly at the time) narrow-mindedness in terms of what I was expecting of Linklater. He was a filmmaker with much to say and would go on to have a variety of different locations, subject matter, genres and characters to say it. Dazed is a fun film, with drama emerging both subtlety and distinctly, despite (and due to) the presence of certain stereotypes (many of which Linklater unsettles with scripted/performance sleight of hand at key points). The film predates much of what Linklater looks into with his next movies and key messages are begun here, to be expanded upon in detail in future output. Dazed and Confused has a universal accessibility where Slacker had a dense, protracted and nebulous screenplay. It seems to make sense that Linklater would demonstrate his ownership of the medium with his second movie, by showcasing easily accessible characters in familiar situations whilst still adhering to his modus operandi—the smaller, intimate, and unvarnished moments that subsist in amongst the grander events of everyday life.

“Hey. Could we do that again? I know we haven’t met, but I don’t want to be an ant, you know? I mean, it’s like we go through life with our antennas bouncing off one another, continuously on ant auto-pilot with nothing really human required of us. Stop. Go. Walk here. Drive there. All action basically for survival. All communication simply to keep this ant colony buzzing along in an efficient polite manner. “Here’s your change.” “Paper or plastic?” “Credit or debit?” “You want ketchup with that?” I don’t want a straw, I want real human moments. I want to see you. I want you to see me. I don’t want to give that up. I don’t want to be an ant, you know?” —Waking Life

With my filmic experience broadening via other directors such as David Lynch, I lost sight of Linklater once more until the new millennium, whereupon I discovered Waking Life (he’d been quite prolific in the interim, with SubUrbia, The Newton Boys, Tape, and School of Rock all being released to varying degrees of interest/success). By this time, I was at the start of my first marriage, about to have my first child, and was moving up in my career too, so my attention to anything outside of my daily existence was negligible (Linklater was also a father now, and was certainly gathering more attention as his movie productions increased in number, and varied in range and genre). I certainly wasn’t expecting to appreciate any film at this point that lacked traditional linearity, or that demanded clarity of attention and understanding (I was tired. A new baby will do that). But Linklater was again about to challenge me.

In Waking Life, we follow an unnamed character as he travels through seemingly real and imagined states of consciousness, interacting with assorted friends, random characters and other fellow ‘lucid dreamers’. Whilst travelling between varying ideas and ideals, he waxes philosophical and engages in a profusion of high-brow conversations of a metaphysical, existential and humanist nature. The film utilises an animation technique known as rotoscoping, with a variety of artists contributing to making each segment as individual and intriguing as the characters and conversations that we encounter.

Linklater appeared to find a way of melting together all of his more esoteric questions and competing notions—questions without answers, and answers without surety. It’s an almost impenetrable cloud of inconclusive thoughts that, in essence, beg to be thought about before (perhaps) reaching a suitable, personal conclusion. Of all the films I introduced to one of my closest friends in recent years, this was the only one he said that he still didn’t really appreciate or ‘get’. I understand that. After all, there is no story beyond journeying with one young man who may, or may not be, participating in lucid dreaming that is actively controlling his dreams in order to interact with other fellow dreamers. But to be fair to my friend, I think he understood it more than he realised. There is no conclusion to be reached or catharsis to have. In fact, at a time when the world was about to be shaken by one of the largest acts of terrorism in the modern age, the film reflects on the core deliberations of what it means to be alive, and the who and why of what that has meant, and could mean. “Dream is destiny,” posits the movie. What do we dream? What will be our destiny? Is there any truth to the statement or are dreams simply dreams, whilst destiny is already outlined for us in some unknowable, preexisting fate?

As a film, it’s almost a documentary, wading into some of the biggest philosophical questions to date. It can lose its audience fairly quickly and is certainly not for everyone. With a film like Dazed and Confused or the Before Trilogy, big scale conundrums that have delighted and absorbed philosophers and thinkers for ages are distilled into present day problems and deliberations, filtered through a character’s own beliefs and attitudes. In this film, these doctrines and ruminations are pure and unfiltered, hard to grasp in one sitting but always interesting (and with visuals that charm even if the dialogue is dense and circuitous). But that’s okay. There’s always another dream/dreamer coming along shortly.

In my own life, after what has been described to me as my own ‘existential event’, I remember rewatching Waking Life with keen interest, absorbing and following up in my own life the works of Camus and Sartre, the Buddha and Neale Donald Walsch (to name just a few). Finding myself at sea, adrift without mooring or a strong sense of self, I experienced conflicting emotions with each new approach that I read. I waited on resonance, to feel belonging, that someone else had experienced something akin to what I was. And that perhaps—perhaps—they had an answer as to how to move forward, to discern and accept what life itself was about.

Despite the fact that I believe I’m still working on that one, I was given plenty to think about and there have been times I have silently thanked Linklater for giving me pause, and fresh avenues of thought to travel. (Though there are other times I kind of wish I didn’t think quite so much!)

Moving forward, Before Sunset appeared in cinemas, with actor Ethan Hawke declaring that he, Linklater and fellow actor Julie Delpy suggested that its first iteration was “[Before Sunrise is] the lowest-grossing film to ever spawn a sequel.” [4] I’m not going to go into detail here as my future article will examine the films, but for the sake of continuity, Before Sunset is absolutely the sequel I had always wanted. Catching up with Céline and Jesse, this time in Paris, arrived at a time when my personal life was undergoing some upheaval in the relationship department and much of the film was actually a painful reminder of what I was losing in terms of myself and what I thought a relationship could be. It wasn’t a similar situation on-screen, but there were realisations at that time—in Jesse’s on-screen life—that were occurring to me in the real world. It was enlightening and it was edifying, and ultimately it spoke to me in the way most of us hope art can.

Skipping ahead, Before Midnight appeared after many more films from Linklater (including Fast Food Nation, A Scanner Darkly, Bad News Bears, Me and Orson Welles, and finally Bernie to name a few!), each an expression of his personality or interests (some more than others perhaps, but each holding a clear interest to him). This latest (and possibly last) film in the Before series following Jesse and Céline, finds them married with two daughters, in the deeply historic country of Greece. Time has caught up to them (and me at this point. I am a single, divorced father, back in the world of new relationships, with emotional barriers and baggage to confront and surmount). It’s a difficult film and one that, I admit, I need to rewatch again before article three in this series in order to reevaluate and hopefully reappreciate it. It was great to be back in the cinematic world Céline and Jesse exist in, so close to our own, but it’s that closeness that perhaps made me uncomfortable. Did I finally find that I wanted real life to piss off, and just exist in a fantasy where things work out? Where the odds are overcome and we don’t surrender to the anger of the moment or resist truly looking inward, admitting that perhaps we got something wrong?

To finish this article on Boyhood seems appropriate. A film that garnered the limelight not just for its success with an audience or the critics, but it was the film to finally gather an appreciation for its director in more widely-known circles. An Oscar contender for Best Picture and Best Director finally gave Linklater a ‘general public’ acknowledgement, despite the fact that many would have already experienced his work via something like School of Rock. But as mentioned at the beginning of this piece, it’s likely they would not have recognised the director at all. What I will say about School of Rock is that, despite its seeming ill-fit for Linklater, it features a strong, individualistic protagonist—an artist who could fit into Slacker—whose music would not be out of place in Dazed and Confused, and who has the heart of Jesse and Céline and the refreshing enthusiasm of Richard Linklater himself.

Boyhood could be seen as a gimmick-led film, having been shot piecemeal over 12 years, and finally being presented to the world as a single motion picture incorporating footage shot in sequence across that time frame. Featuring a main character named Mason, we follow his journey from 6 to 18 years of age, experiencing episodes of his growth from boy to manhood. In addition to his transformation, we also undergo the growth of his parents, reflecting on bringing children up in the world whilst also maintaining a sense of self and somehow navigating the complications that maturity and the passing of time bring.

Winner of such awards as Best Director (Berlin International Film Festival, BAFTA Awards, Golden Globe Awards etc.) and Best Film (same, and more), Boyhood (rightly or wrongly) could be seen as something of an accessible accumulator of many of Linklater’s themes. A smattering of his previous considerations hidden in plain sight through the experiences of one child growing up from 2002 through 2014. It’s not difficult to see elements of most of his personal films in Mason’s parents or friends; his efforts to establish who he is and what he wants from his life to come; the understanding that not everything in life has purpose or meaning (or that everything does!); expectations versus reality; moments that remain with us despite the perception of triviality at the time. There’s much in Boyhood that Linklater has been examining throughout his career, and in the next part of this trilogy of articles, I’ll be taking a look at what some of those fundamentals have been.

TO BE CONTINUED…

[1] http://collider.com/boyhood-interview-richard-linklater-ethan-hawke/

[2] https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/slacker

[3] https://www.austinchronicle.com/screens/2001-06-29/82235/

[4] https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/the-present-and-future-ethan-hawke-on-the-before-trilogy