Our coverage of the 8-part Amazon Prime series The Romanoffs from Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner continues with Lindsay Stamhuis’s analysis of the seventh episode, “End of the Line”

There’s a moment in this week’s episode of The Romanoffs that absolutely blew me away: where the tension of what we’ve seen up to this point dissolves into the kind of existential angst that hasn’t quite marked this series up until now, but which was all over Mad Men.

It was the moment when I realised that I was watching great television again.

Joe Garner (Jay R. Ferguson) and his wife Anka (Kathryn Hahn), an American couple in Vladivostok to adopt a child, meet their new daughter Oksana in the Russian orphanage. Oksana has had a rough childhood so far: born to a teenaged mother in a small village five hours away from Vladivostok, she was given to the girl’s grandmother, who was too old and frail to care for the baby and surrendered her to the orphanage. She is six months old. Overcome with emotion, the new mama and papa attempt to play with her, showing her the rattles and balls and dolls that they brought with her. Trying to bond. But Oksana doesn’t make a move. She doesn’t react. She doesn’t cry. She barely does anything. We see this all play out from Oksana’s point of view, laying on the floor on a polka-dotted blanket, staring up at the faces of her new adoptive parents as they go through emotions from overwhelmed and exhausted to bewildered to worried.

The anxieties of these parents-to-be as they wing their way around the world, deal with corrupt government officials, part with their money in shady dark parking lots…we think we know the story that we’re going to be told. But this is not that story, and it’s thirty-odd minutes into the episode is when we discover it.

The other shoe starts to drop, incrementally, when another, older child at the orphanage points to Oksana in the hallway. “P’yanitsa, p’yanitsa!” she says. It means “drinker” or “alcoholic”. Oksana, Anka decides, has fetal alcohol syndrome. She believes they were duped, that the child they were led to believe they were adopting had been switched out somewhere along the road, and even after fifteen years of trying to have a baby, she decides she can’t raise this one.

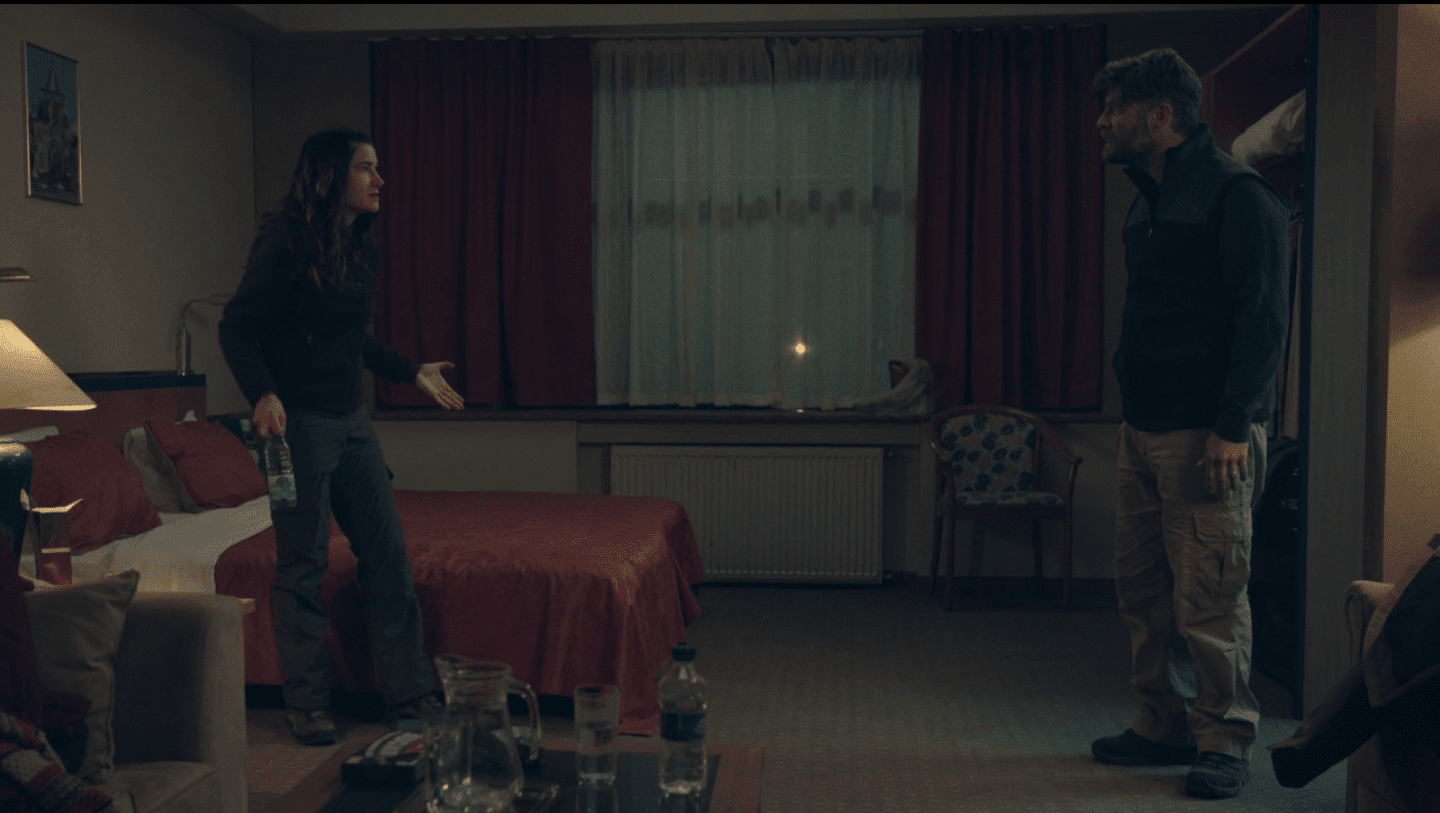

It’s a heartbreaking, profoundly disturbing turn of events. Joe and Anka’s subsequent fight about whether or not they will go through with the adoption calls to mind, again, the best and most tense scenes from Mad Men (that this episode was co-written by Maria and Andre Jacquemetton, Matt Weiner’s frequent Mad Men collaborators, should come as no surprise at this point; it’s one of the best episodes of The Romanoffs as far as I’m concerned). The anger and resentment between these two characters is overwhelming. Anka feels she’s sacrificed her body, her health, and years of her life for a child that she isn’t going to get because, in her mind, her baby should be perfect, should be exactly what she chooses; she refers to Oksana as “that baby” and “it” throughout this scene, which only underscores how incredibly detached and distant she has become from this process at this point. She looks at this whole thing as a transaction, and they are customers. $50,000 gets you the ability to be picky. This is the system they’re in. She’s not wrong.

Joe, on the other hand, can’t believe that his wife is willing to throw away what he assumed they’d always wanted because Oksana isn’t perfect. He doesn’t view this as anything other than the end result of a long journey towards becoming a family. It is what it is, but isn’t that how it should be? His tepid rationalisations—about not buying into the milestones as the be-all, end-all indicator of a baby’s health, about the developmental delays that can sometimes result in children who aren’t held or interacted with much in infancy, about how she may have been born premature—do nothing to win over Anka, who can only see the lost promise of what she believes she is owed, what she believes she has paid for.

“I can’t believe you’re like this,” Joe says to her.

“Everyone is like this,” Anka replies.

It’s a mark of truly great storytelling when characters can say a line like that and you can believe them. This story has enveloped Anya and Joe in such a way that no matter what they do or say, they’re never going to be wholly right or wholly wrong. This is about as morally grey a story as anything I’ve watched in the last while.

Shared traumas aside, we learn here that Joe was abandoned by his father as a child, and that Anka carries some burdens of her own as a result of her Romanov ancestry. The Romanovs, we’re told by their Russian contact Elena, are considered saints in Russia, and Anka is not a saint. She tells us so; she shows us so. She admits that, had she carried her one successful pregnancy to the point where amniocentesis could have been performed, she would have terminated the pregnancy had their fetus tested positive for something like Down syndrome. Who says that? Apparently, Anka does. Unlike so many other characters, she knows who she is and is not afraid to be that.

Does that make her craven? Perhaps. Heartless? I wondered about that more than once during the hour and twenty-seven minute runtime. Did I sympathise? Yes…and no. But…yes? Maybe? No! Not at all! Could I have made this same decision? I don’t know.

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe Anka is right to dig in her heels and refuse the con job that’s trying to be passed off here. But Joe can’t possibly be wrong to want to take this child—who clearly has something the matter with her, whether it’s related to fetal alcohol spectrum disorder or not—back to Los Angeles, where Western medicine can work its wonders and she will be given all the benefits that her privileged parents can afford. Who are we supposed to side with?

Their Russian contact Elena (Annet Mahendru) is similarly ambiguous. It’s easy to want to cast her as modern day Natasha Badenov swindling these poor, distraught parents-to-be out of their money, sending off to America a child who would be otherwise unwanted in its (emotionally and physically) cold native country. She dresses in black, wears fur, is stiletto-thin and just as sharp, icy; her clipped English a discomfiting bolster for Joe and Anka to cling to in this foreign land. But as she tells us about Russia, about the remote eastern outpost at the end of the world that is Vladivostok, and we see the faraway look in her eyes, it’s impossible to ignore the fact that perhaps she is trying to do what is right by Oksana. This is a place where life is not particularly valued. We see the same dead dog, twice, covered in snow and left for the spring thaw, whenever that comes; men with guns make you smile nervously when you see them, but smiling is verboten (“Prekratite ulybat’sya”, Elena tells them. “That means don’t smile. People will think you’re a mental patient.”), which tells you everything you need to know about the state of mind of the people of the Russian Far East. What future could Oksana possibly have in this place? Better she goes with the American mama and papa, he who works at Universal Studios and she who is descended from saints. What’s a little lie if in service of this greater good?

Morally grey; I know.

In the end, Anka and Joe appear to go through with the adoption only to refuse Oksana at the last minute. What follows broke my heart: Elena and the orphanage director present Anka and Joe with a different child, one who coos and squirms just like a normal baby does. The parents-to-be melt. They take their daughter in front of the judge, promise to take care of her medical needs, and Joe gives a good line about preserving Anka’s heritage and promising to raise “Oksana” (the little girl is really named Katerina, but for the purposes of this adoption, she has to become Oksana; she’s a literal replacement) with an awareness of the special place she came from. The subtitles here were what did me in: Katerina fussing…Katerina fussing…Katerina fussing…

If Oksana had fussed a little more, she would be the one going to Los Angeles. She would almost certainly receive a diagnosis and medical care to match. She would most definitely have a better quality of life. But Oksana didn’t fuss. “Oksana” did.

The episode ends with the happy couple on the plane heading home, now a family of three. Anka got what she wanted, and so did Joe. But they both have to live with the knowledge of what happened in that city at the end of the railroad tracks in eastern Russia in the winter of 2008. That the credits play over Billy Joel’s “Just the Way You Are” seems like a cruelly ironic joke at this point. Has anyone in this story been loved just the way they are?

As strong as this episode is, there are a couple of strange almost missteps that left me scratching my head. One subplot involves a single mother adopting a little boy who is also similarly troubled. He cries a lot, refuses to eat any food aside from “Bush wings”—the pieces of the chicken Americans refuse to eat, which are fried in lard and fed to the children; so-called after President Bush, who was the first to send them there. (I can’t find confirmation about this factoid, but if I do, I’ll update this page accordingly)—and when she first met him, his adoptive mother noticed cigarette burns on his legs. She wants nothing more than to take her baby boy away from this horrid place, in spite of his apparent “flaws.” Anka refuses Oksana on a suspicion. I’m not a fan of any story that pits mothers (or women in general) against one another for the purpose of painting one as good and the other as bad, and that’s what this seems to be doing. I wish it had a bigger payoff than it did.

Another miss for me was the brief interlude after the fight when Joe goes for a walk outside and encounters a stray dog he tries to save, while Anka visits the hotel bar and encounters a prostitute, whose bleak outlook on life might have been the thing that convinces Anka to go through with the adoption come morning (though that doesn’t last). Joe’s transparent attempt at saving an unwanted thing comes across as needless, though it does link back to his deep wounds from being similarly abandoned himself. We know that this is what he wants to do; we don’t need to see him do this. Similarly, Anka encountering the prostitute doesn’t add a whole lot to her character or colour her motivations. Perhaps it helps her understand the hopelessness of life in this city where she is ready to abandon Oksana. But it seems to me, in retrospect, like unnecessary padding around a story that ought to give us bumps and bruises along the way. We should be questioning our privileges, our assumptions, and it should be uncomfortable and tearful and starkly lit in sickly shades of hospital green and greyish airport fluorescents.

The typical Romanoffs emphasis on the haves and have-nots is absolutely present. There’s also that sense of American Romanov Descendant Delusional Entitlement, which at this point ought to have its own page in the DSM-V—whether it’s her comedy of manners with the prostitute at the bar or her insistence that, actually, The Beatles were wrong and money can buy you love, Anka displays a kind of startling, upsetting arrogance that flies in the face of everything we understand about the people in these situations. Desperate and at the end of the line, Joe and Anka make a terrible choice. Was it the right one? Will they regret it? Who knows.

What I do know is that I will be haunted by this episode for a long time.

Post Script:

- This episode takes place in 2008, making it the first of these episodes that I can remember (correct me if I’m wrong) to take place wholly in the past. I can’t find much to back up any particular theory about why this is, except a for New York Times article from May of that year discussing the tightening of regulations and restrictions around foreign adoptions that seemed to plague the latter years of the Bush administration. Time may indeed have been running out for Joe and Anka on more than one front.

Want to talk more about The Romanoffs? Join this sub on Reddit, and/or hit us up on Twitter: @linzstam & @caemeronCC. Cæmeron and I will be back again next week with our roundtable discussion of the finale. Stay tuned, and thanks for reading!