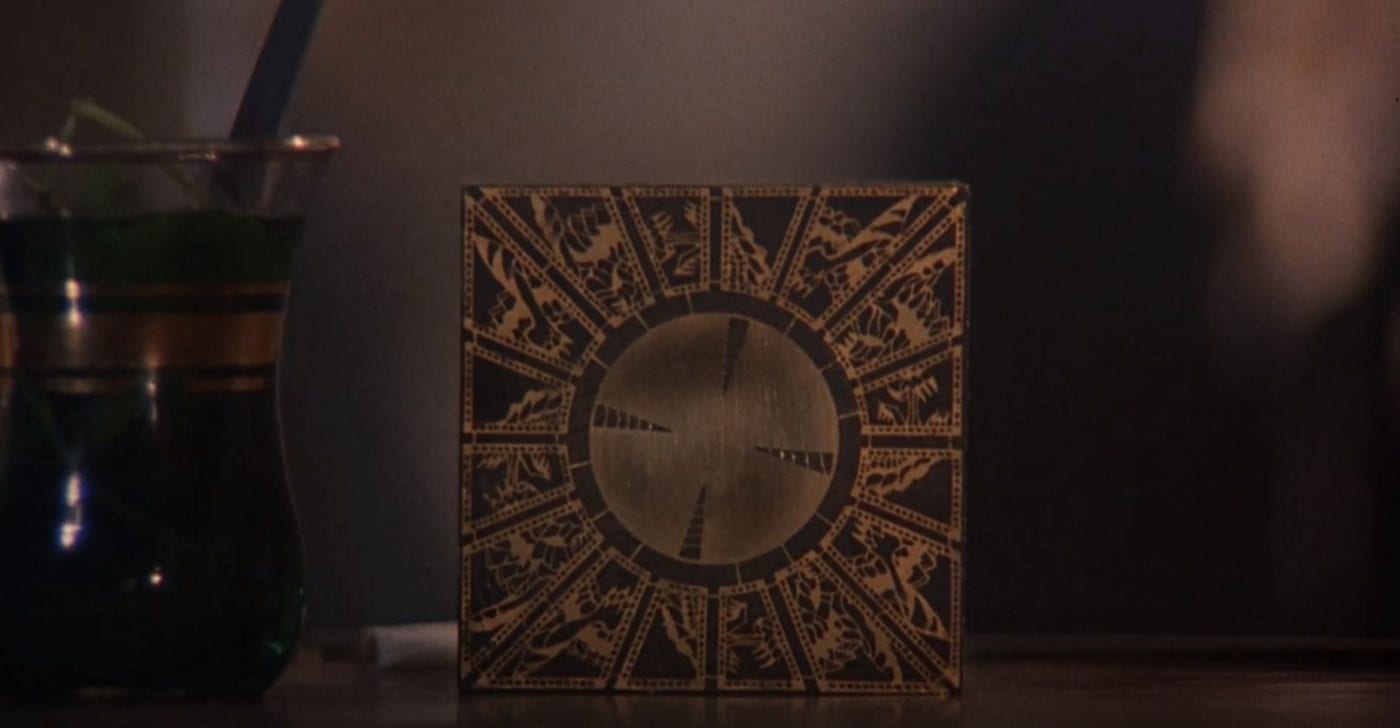

There have been many Pandora’s boxes in film history: the box at the end of Kiss Me Deadly, the ark at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, the little blue box at the end of Mulholland Drive. None are perhaps as visually striking or popular as The Lament Configuration, the fictional Lemarchand’s puzzle box, which is all of a sadistic Rubik’s cube. Further, it is a key to the darkest corners of Clive Barker’s imagination. Those imaginings remain unique, dark and sole visions, but there were as many influences on him as he influenced with his art. According to Paul Kane in his encompassing work The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy, “…[W]ith regards to Hellraiser, Barker’s grandfather was a ship’s cook who brought him back exotic presents from the Far East. One of these just happened to be a puzzle box that Barker spent hours trying to solve. As a child, Barker was also obsessed by a book on anatomy by Andreas Vesalius, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543). Its pages depicted skinless figures in delightfully graceful poses.”[1] As early as 1995, Dr. Angelina Whalley’s and Dr. Gunther von Hagens’s artistic and educational traveling exhibition, Body Worlds, seemed as if it could have been inspired in the Cottons’ attic right alongside the gelatinous reforming of Frank’s corporeal body. It is hard not to see the similarities in the anatomical exhibitionism, intentional or otherwise. Those summoned Cenobites of the Order of the Gash had so much to show us.

My first memory of seeing The Hell Priest, a character audiences quickly named Pinhead, was on the wall of another doctor in my youth, namely Doogie Howser. Okay, so he wasn’t a real doctor. Still, outside of the newspaper advertisements for the movie I would see next to my local theater show times, my first fascination came from that poster on Doogie’s wall as his friend Vinnie climbed through his window. (I’m working to confirm if this is a constructed memory.) Barker and his Vice President for Seraphim Inc., Mark Alan Miller, have since those early days worked hard to condemn the “Pinhead” nomenclature in The Scarlet Gospels, a novel of the character’s final days, and its prequel Hellraiser: The Toll. “And the creature it eventually summoned went by many names. To those foolish or suicidal enough to indulge in insult, he was called Pinhead.”[2] “Whatever torments he had planned for these last victims—and his knowledge of pain and its mechanisms would have made the Inquisitors look like school-yard bullies—it would be worsened by orders of magnitude if any one of them dared utter that irreverent nickname Pinhead, the origins of which were long lost in claim and counterclaim.”[3]

In a piece I wrote covering Shout! Factory’s Blu-ray box set for Critters, I stated that “All of these franchises have these central character arcs that make up the best definitions of the series.” For some, Tommy fulfills that role in Friday the 13th. For others, it is Nancy in A Nightmare on Elm Street, and for many fans of Hellraiser, she is Kirsty Cotton. Kirsty’s story spans Parts 1 & 2, both of which are currently available on horror streaming service Shudder. The first film appears as an episode from Joe Bob Briggs’s summer marathon for Shudder, offering audiences film trivia as well as Briggs’s classic Drive-in body count. Those include: “78 gallons of blood, 147 gallons of slime, 2 breasts, 10 dead bodies, chains, barbed wire, character actor taffy pull, flaying, clawing, manacling, gratuitous body parts, gratuitous maggots, devil sex, blood gurglin’, gloppola skeleton chasin’, head bashin’, rat-impaling, rat skinning, face nailing, claw hammer fu,…”[4] etcetera.

To contextualize it for those new to the franchise, Clive Barker’s novella on which the first film is based, The Hellbound Heart, arrived in 1986. He would take on the task of directing the film for release in 1987. This would be the first of his writings he would direct into feature-length films. He would go on to direct Lord of Illusions from his short story “The Last Illusion” and Nightbreed from his novella Cabal. The latter is in development for a series on the SyFy channel. As stated by Sarah Trencansky in her essay “Final Girls and Terrible Youth: Transgression in 1980’s Slasher Horror,” “…[T]he legacy of the three major horror characters to emerge during the 1980s, Freddy Krueger of A Nightmare on Elm Street, Jason Voorhees of the Friday the 13th series, and Pinhead of Hellraiser, lives on as the virtual definition of film horror today.”[5] Hellraiser was indeed coming after the other two franchises were well into their sequels—Friday the 13th: Jason Lives (1986) and A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors (1987). Other horror movies for 1987 include Evil Dead 2, Near Dark, Monster Squad, Angel Heart, and The Believers.

Clive Barker’s Hellraiser presented horrors altogether different from these films, the slapstick possessions of Evil Dead, the brujeria of The Believers, the Lucifer of Angel Heart. Clive Barker erased the victimhood of its protagonists and even antagonists, making them instead accountable to their inner desires. What they received in turn for their lusts and curiosities was a payment in erotic atrocities and mutilation. This is also framed by Aviva Briefel in her essay “Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation, and Identification in the Horror Film:” “Clive Barker’s 1980s Hellraiser series (originally titled Sadomasochists from Beyond the Grave) is populated by humans who turn into monsters by seeking the most intense experiences of pleasure and pain: once they solve the cursed puzzle box, their flesh is ripped apart by pins and hooks and they realize that ‘Some things have to be endured, and that’s what makes the pleasure so sweet.’”[6]

Fresh to Barker’s worlds, audiences in 1987 might not have realized that Barker sees all of his works in a kind of monster-filled fantasy world as opposed to traditional horror. He would prove this in his following writing career with novels Weaveworld, Imajica, The Great and Secret Show, and Everville. In Hellraiser Frank doesn’t simply escape from Hell, he escapes from The Wastes of Hell, home to the Cenobites and a kind of district of the larger whole. While Hellraiser concentrated on the affair of Uncle Frank and Julia—it turns out the human could be as frightening as the monsters, a theme more fully realized in Nightbreed—Hellraiser II: Hellbound introduced fans to a mythology for their celebrated “Pinhead,” or the Hell Priest.

Where the characters of Julia and Frank are concerned, though, Julia was originally purposed as the true horror icon of the film, a role usurped by Pinhead based on fandom’s demand. That may add to Barker’s frustration with Pinhead. The intention, as Kane states, was that “Hellraiser scratched beneath the veneer, in much the same way David Lynch did with small-town America in Blue Velvet (1986). Barker’s film is a metaphor for what really goes on behind the net curtains in certain British households, and not just because of its S&M overtones.”[7] Following the first two films were a slate of sequels that seemed to change the Pinhead character into one lacking the integrity of the original concept.

Given that, let’s imagine that just as there are several Lemarchand Boxes or keys to this world, there are different pathways through this franchise. In the first, one could watch the series of films from Part 1 straight through the more recent Hellraiser: Judgement. In a second, one could seek their way to The Scarlet Gospels (Pinhead’s demise) by watching Parts 1 & 2 as well as Lord of Illusions (to get Barker’s Occult detective Harry D’Amour’s story, including short story “The Last Illusion” and novel Everville). A third option exists, and that is to watch Part 1, read Hellraiser: The Toll (Kirsty’s continued story ignoring Part 2), and then The Scarlet Gospels. If you are lacking that dedication, Parts 1 & 2 make up a perfect story arch for the Kirsty, Julia, and Frank story line, and again, both of these parts are available on Shudder. For those wanting to know more, Shudder also includes the documentary Leviathan: The Story of Hellraiser and Hellraiser II. So, given all of these options, I have to ask: what is your pleasure?

Works Cited

[1] Kane, Paul. The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy. (North Carolina: McFarland, 2006), 8.

[2] Miller, Mark Alan. Hellraiser: The Toll. (Burton, MI: Subterranean Press, 2018), loc. 278, Part 1, Chapter V, 6th paragraph.

[3] Barker, Clive. The Scarlet Gospels. (New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 13.

[4] The Last Drive-in with Joe Bob Briggs, “Hellraiser,” Aired July 13, 2018 on Shudder. https://www.shudder.com

[5] Trencansky, S. (2001). “Final girls and terrible youth: Transgression in 1980s slasher horror.” Journal of Popular Film and Television, Xxix(2), 63-73. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1745748993?accountid=7098

[6] Briefel, Aviva. 2005. “Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation, and Identification in the Horror Film.” Film Quarterly 58 (3) (Spring): 16-27. https://search.proquest.com/docview/212277866?accountid=7098.

[7] Kane, The Hellraiser Films and Their Legacy, 32.