To watch a TV show is to enter into a fantasy; a world, which—no matter how “realistic” it may be—is not quite ours. With the best shows, though, that fantasy comes to inform one’s perspective on reality: you think about it even when you aren’t watching; it colors the way you perceives things. We become like the dreamer who dreams and then lives inside the dream. Whether or not the dream is pleasant is a further question.

Mr. Robot throws us into the world of Elliot Alderson, who is not OK. We know that from the beginning, even if we don’t know the extent of it. As much as we may empathize, or even identify with Elliot, he is an unreliable narrator, and one of the most striking things about the show is the extent to which this informs it. Events unfold from Elliot’s perspective, and this is how we see them—hearing “evil corp” instead of “E Corp” right along with him, for example—but what we (presumably) never see is objective reality; there is no “God’s-eye view” here. Even those scenes in which Elliot is absent are potentially suspect—whose perspective is this? Perhaps we don’t know, and perhaps it doesn’t matter, but the structure of the show implies that it could not be some neutral, detached point of view.

That would be incongruent with the way in which what is shown is clearly filtered through Elliot’s perspective, particularly in Season 2. Even if there have been no similarly strong indications that we are seeing things from Darlene, or Angela’s point of view in other scenes, e.g., my tendency would be to suggest that we are; it’s just that these never represent a distortion as large as that of Elliot pretending to be staying with his mother when he is actually in prison.

We have a sort of knee-jerk tendency to take what we are seeing as a depiction of reality, which Mr. Robot calls into question. There is unreliable narration in True Detective, for example, but we naturally think that what we see is what really happened and what we hear in the retelling of events contains the falsity. To be placed instead in a situation where we cannot necessarily trust our own eyes, either, is far more complicated.

Mr. Robot throws us into Elliot’s madness. He hears “evil corp” instead of “E Corp” and thus so do we (until the third season when his views begin to change). He imagines himself at his mother’s instead of in prison, and that’s how we see things. He experiences conversations with his dead father, and we are right there along with him.

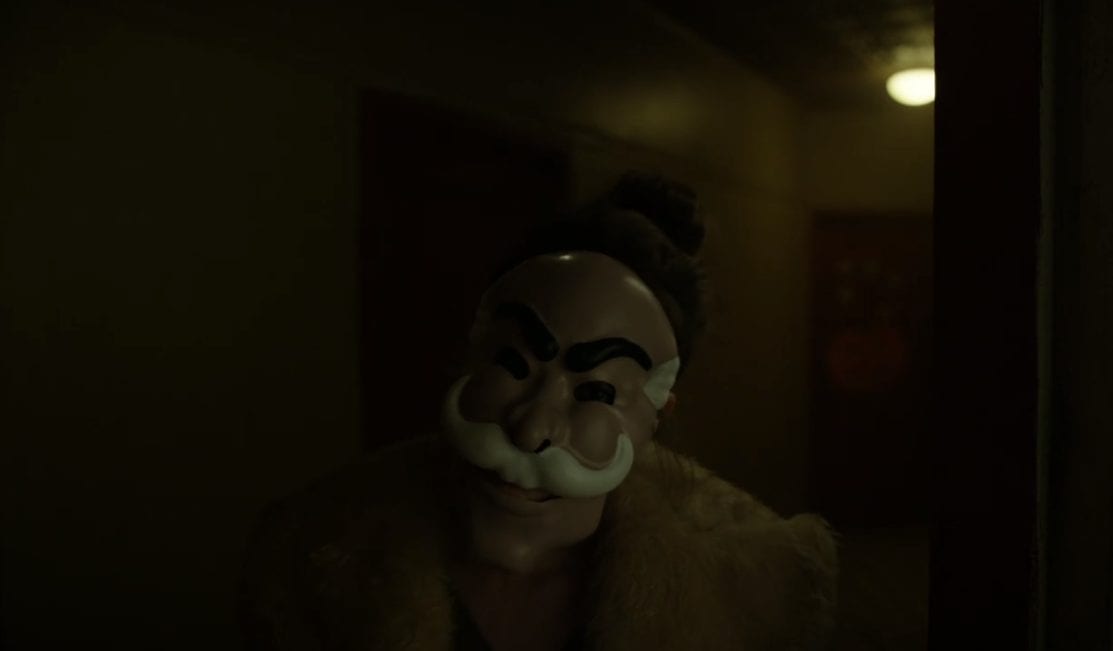

In watching the series over again, this is something that I found myself thinking about. Knowing that Mr. Robot was a figment of Elliot’s mind from the get-go, does it work to collapse them on a second viewing? In one sense it does, as is many scenes one can simply imagine Rami Malek saying the lines that are delivered by Christian Slater, but in others it really doesn’t, as when they are talking to one another in front of the other members of fsociety. In scenes like this, is Elliot just standing there talking to himself out loud? Or is it in his mind to where he just seems spaced out to those watching? I don’t think we know. And when we see Mr. Robot talking to Elliot via earpiece as he infiltrates the facility to sabotage the heating system, what do we make of those times when he seems to also communicate with Romero and Mobley? It’s not that the narrative is inconsistent, so much as the narrator is unreliable. Trying to work from the basis of what we see and hear to something like the objective reality of events is largely a fool’s errand.

It further would not be quite right to suggest that Elliot breaks the fourth wall when he talks to the audience, insofar as the phrase implies breaking from the narrative frame, or exiting it. Rather, if the fourth wall is broken in Mr. Robot it is in the other direction—he implicates us in the narrative by speaking to us as his “imaginary friend.” He becomes angered at the notion that we might know more than he does, and even at times asks for our help. Elliot doesn’t break the three walls of the narrative; he pulls us into the story, making us a part of its action.

This move of making the audience a part of the story deepens the effect of the show. What is real and what isn’t? Are those men in black following our friend Elliot, or just sharply dressed businessmen who have nothing to do with him? The overall effect is a bit paranoiac, as we see events from Elliot’s point of view not just narratively, but in terms of how the show is shot and framed cinematically.

This may be the case to an even stronger degree for someone who, like me, lives in New York (I even used to live around the corner from the location of Elliot’s apartment). The city can be strange. There is chaos, and noise. There is a certain ethos of not looking at one another (which isn’t rudeness, but respect), such that when someone does it can lead one to question why. Why are you paying attention to me, in this city of millions?

So when Elliot encounters the world’s worst busker, in a scene where the effect of the discordant music is clearly meant to illustrate his paranoid mental state, it nonetheless comes across as something that would be entirely possible. I wouldn’t be surprised to encounter that guy during my commute tomorrow, really.

It is not for nothing that Mr. Robot takes place here (or in some alternate reality version of New York where you can transfer to the Q from the F at the Church Ave stop), and more broadly it is worth noting the extent to which it plays within the context of our world. Barack Obama speaks in response to the hack. The talking heads on the news programs are the same as in real life. Donald Trump appears; giving a speech that he gave in reality, as he campaigned for President. Perhaps this is not our world, but it is close, and maybe too close for comfort.

As I allowed Mr. Robot to suck me into its orbit, rewatching the first two seasons before I (finally) watched Season 3, I found it coloring my perceptions of reality. However subtly, a level of imagining that I was like Elliot hacking into some system crept into my experience of typing at the keyboard, and my day to day life in the city began to feel tinged by a certain paranoia. Why is that person looking at me? Does this guy talking me up randomly on the subway have some hidden agenda? Perhaps binge-watching this series isn’t the best idea.

Yet this gets to part of what makes the series as great as it is: it blurs the lines between fantasy (or delusion) and reality, not only within the context of its narrative frame, but in ways that extend beyond it. It doesn’t allow us to be detached observers, because we are part of this story as his “imaginary friend”. Do we want Elliot to succeed? Are we on his side? He’s worried about that, too.

This fits with the fact that the crux of Mr. Robot is the question of what to do in the face of late capitalism, and an examination of what it does to us. As Darlene suggests when Elliot inquires about her panic attacks, is it really sane to act like everything is OK? “Since when did pretending that everything’s OK suddenly become the almighty norm?”

Elliot’s mental illness is not divorced from this broader question. In their two-volume series on Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari suggest that the same logic is at play in both: a movement of de/re-territorialization.

To get at this we have to first discuss the operative notion of territory. The point is that the territory is at play in how one makes sense of reality. It could be marked visually, as by a fence, or in other ways, such as urine sprayed on various trees, for example. It is not a distinctly human thing, that is. But in human terms it involves not only a demarcation of physical space, but something related to a more conceptual, or psychological one. The territory is psychosocial.

At the psychological level, this involves the way that one makes sense of the world; the coordinates of how you define reality. At the social level, it gets to the structure of one’s culture, politics, etc. But what is distinctive about Deleuze and Guattari is that they mark no strong distinction here: the personal is not separate from the political; it is a matter of micropolitics. And the psychological, equally, is not something set apart from the broader social reality in which it is embedded. Desire directly invests a social field. The neurosis, or psychosis, is not just about mommy and daddy, or the Oedipus complex: it is about oneself in relation to a much broader psychosocial reality. This is the thrust of their collaborative work: Freud wasn’t wrong so much as he was reductive, taking, e.g., a fantasy-complex about a pack of wolves and reducing it to something about daddy.

Capitalism, in contrast to all previous social formations, is defined by deterritorialization. Marx already recognized this, when he (and Engels) contended that it was not Communism seeking to undermine religion, etc., so much as this move was already occurring through the forces of capitalism itself.

Cultural mores, religious dogma, etc., get undermined as everything is subsumed into the logic of the almighty dollar. Perhaps there was a territory—a set of markings that helped one make sense of the world—but capitalism intrinsically disrupts such things. The website has a new layout now. Your phone updated itself and no longer works in the same way. People no longer follow the unwritten rules you expect them to; they might try and plug a phone in onstage during a theater performance. And, in broader scale terms, our social/cultural values are constantly changing.

But with every deterritorialization there is a reterritorialization: new values and mores take the place of the old. One can hardly live now without a smartphone, even though we all lived perfectly well before they existed a little over ten years ago. Or, better, how is it that Christianity in the United States has come to be dominated by people who want to keep out refugees and think that being rich is good, when in the New Testament Jesus seems to make it pretty clear that the rich aren’t getting into heaven?

In each case of reterritorialization, concepts have been given another context, or another frame. But it’s not stable. The intrinsic movement of capitalism will be to deterritorialize them yet again. There are no stable identities, just flows: of money, of code, of desire itself. The question is how to capitalize on them before this river washes away the boundaries of the territory that has been temporarily established, or how to create a new one in the aftermath of that flood.

This is what Mr. Robot gets to as it explores the fallout of 5/9—an event of massive deterritorialization. One might fantasize about destroying Evil Corp, LLC but insofar as the structure of capitalism remains intact, it will have little effect. There are those in positions of power ready to capitalize on the event, to impose a new structure (like “E Coin”) that will allow them to ultimately benefit even from the thing that was meant to destroy them.

It is to this extent that it makes sense to see Whiterose suggesting support of Donald Trump. I recall during the 2016 election (and this was while the primaries were still going on) suggesting to a Trump supporter in my family that Hillary Clinton was saying she was really good at playing the game; Bernie Sanders was suggesting that we need to change the rules of the game; and Trump was saying we should kick over the board. To which he replied, “Yeah!” (let’s kick over the board).

In many ways, Mr. Robot examines the consequences of doing just that. I don’t want to equate Elliot with Trump, but the actions of 5/9 do seem to represent a certain fantasy about kicking over the board and starting over. Wipe things clean. Erase the debt. Kill Evil Corp, which stands in for any and every massive international corporation you could think of, and it will all be better.

Except, it won’t be. Things aren’t that simple. As complex as fsociety’s plan is, it is still too simplistic. The reality is Price and Whiterose working behind the scenes, as they represent those forces that will work to re-establish the status quo of corporate dominance. As representatives they may be too simplistic too—in the real world those forces may be far more complex and less along the lines of men smoking cigars and conspiring in a smoke-filled room—but they nonetheless represent forces that feel all too real, even to those of us who resist conspiratorial thinking.

In this regard I find Tyrell Wellick to be perhaps the most fascinating character in Mr. Robot. We might be tempted to view his actions as motivated by a petty desire for revenge or something like that, but it is clear that he is more complex than that. What drives this man? To what extent is he on board with Elliot/Mr. Robot’s vision, and to what extent is he driven by more self-interested motives? In many ways I feel like that remains unclear.

And whom do we root for, now? Elliot, who is trying to “undo” the hack? Darlene, who seems right there with him? Dom, who has been sucked into the orbit of the Dark Army? Or maybe the Dark Army itself and Whiterose’s agenda? (I have to admit being fairly compelled by her, at least until the Trump stuff and some other things—BD Wong is great).

I think the answer has to be Angela. At least for me, it is, considering those who are left standing. And I don’t know where we are going with Season 4, but I think there is a good chance it will recognize that.

Of course, we don’t need to root for anyone; that’s not the point. The point is about the difficulty of living in this world; the tendencies towards mental illness and so on. The point is that our fantasies falter as they confront reality.

What did Whiterose tell Angela? And was it manipulative bullshit? All indications are that it involves some kind of belief in alternate realities and the possibility of accessing them. Is there any chance of that being what plays out in the world of Mr. Robot? I doubt it. It seems more likely that this is bullshit, or a delusion. But while Whiterose may well believe her own bullshit, what persuaded Angela so deeply? Was it simply a desire to believe? I struggle to buy that; Angela is not an idiot. If anything, she has consistently been the sharpest character on the show. Unless, perhaps, the point again is about the power of a delusion gained through one’s will to believe.

Mr. Robot is a quirky title but it also gets to the heart of thing: to what extent are our responses to the world automatic, and unthinking? To what extent do I pin my decisions to someone who is not me? When I say, or think that I “have to do” x, what are the forces in that “have to do”? And, then, is there something in me that works behind my back? Are there ways in which I undermine myself?

The answer is probably yes, even if it is much more mundane ways than we see with Elliott; even if the effects feel less severe. Yet my world is fundamentally structured by a narrative that is mine. We each experience reality as if it is our own story. Thinking you see and hear your dead father may be delusional, but aren’t there more banal ways that each of our lives are similarly structured? When I subvocalize—working out things I might say to a friend, a lover, an ex—am I not talking to myself even just in my mind? And isn’t the way I perceive myself day-to-day meaningfully structured by my point of view; how I see myself in relation to the world?

That’s not a problem insofar as the story of one’s own life that one tells oneself is what provides it meaning. In fact, without such a thing you might well fall into madness. But the forces of (post)modernity and (late) capitalism constantly threaten us; they constantly undermine us. We are made to feel as though this structure, where Evil Corp rules everything and we struggle just to live, is an objective reality; not something we could do anything about any more than the weather. The economy gets cast as a force of Nature, rather than the sum result of a number of human decisions.

Perhaps the easiest thing would just be to go along, as when Elliot gets his Starbucks, or becomes a blank-faced emoji on the train, but “since when did pretending everything is OK suddenly become the almighty norm?” If Deleuze and Guattari are right, it doesn’t make any sense to blame the individual, as if mental illness were some moral failing. The psychological problem and the social problem are not separate.

How can I be OK when the world is fucked? But, also, is there anything to be done to fix it?

A good read Cameron and fertile territory. Interesting to remember that robot means slave – I think derived from Slav the people who nslaved by Vikings. I suppose the question is is how can one be free in a world where to take another post modern track that reality is a simulation, and we can never be certain subjectively or objectively that any thing is real.