One of David Lynch’s most widely quoted remarks is “I want a dream when I go to a film.” He’s offered a list of films that deliver a dream so well he’d watch them “every other day if [he] had the time.” The list is very short and very consistent. This week’s Backstory Investigation explores a French comedy from 1958 that’s always on Lynch’s list: Mon Oncle (in English, My Uncle) directed by Jacques Tati. This choice offers a chance to investigate one significant source of inspiration for the integral style of humor that’s as technically sophisticated as it is broadly appealing in Twin Peaks. Plus, Lynch invokes uncles both inside his cinematic fictions and when addressing fans and interviewers, so a film with Uncle in the title merits an attentive screening.

I’ll start by saying that if you’ve never seen Tati’s Mon Oncle, it’s extremely fun on its own terms and makes for a great mixed-age screening experience. The chiefly physical humor can appeal to a wide range of ages, and much of it emphasizes the visual rather than verbal setups and punchlines. Even as dialogue is downplayed, however, Tati crafted the film’s sound exquisitely to merge the best attributes of silent and sound. Just look-and-listen for the exaggerated vvvvvp sounds emanating from Madame Arpel’s synthetic clothing when she walks and the staccato clickety-clacks when the administrative assistant at Plastac, the plastic hose factory where Mr. Arpel is a manager, hustles as quickly as her ankle-length pencil skirt will allow. So, to watch Mon Oncle is to glimpse the brilliance in surreal humor including sound innovations that inspired Lynch in general and Twin Peaks in particular.

One of the funniest components of the film is a running gag centered on a fish-shaped fountain in the front yard of the Arpel family–Monsieur and Madame Arpel and their mischievous son, Gerard, to whom Monsieur Hulot is an uncle, and a weird one at that. The film prepares spectators for the fountain by focusing on a fish of approximately the same shape near the start of the film when we first encounter M. Hulot, the uncle, at a street market. He steps up to a vendor to inspect some vegetables, and the camera cuts from Hulot to a shot under the vendor’s table where a wandering dog comes face to face with the sharp-toothed face of a large fish protruding from Hulot’s bag. The dog looks alternatively terrified and terrifying as it growls out warnings. The dead fish looks, of course, impassive. And we are brought into a cinematic mode that make a multiplicity of what would conventionally appear to be the simple act of one person shopping for veggies. A cinematic mode of layers and misperceptions, where a dead fish meant for dinner is also a surreal catalyst for comedy. It’s not hard to imagine why a fish got into that percolator.

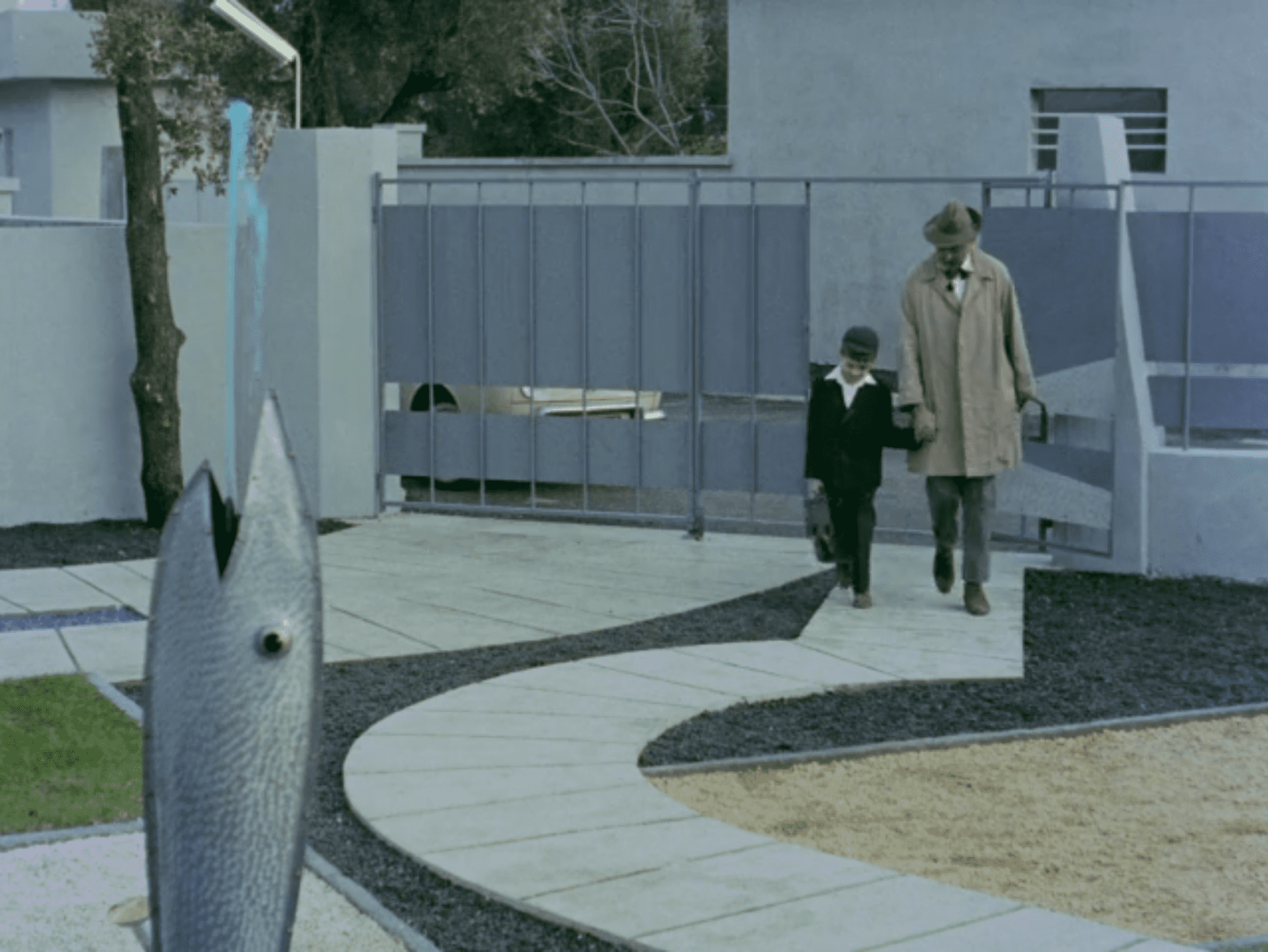

The short sequence of Hulot, the fish, and the dog could easily have been a one-off gag, but it persists when the film takes us onto the grounds of the Arpel home. The Arpels house exemplifies modern architecture with sharp geometric shapes and decor that is technological and mass-produced to deliver a ready-made ideal free of idiosyncrasies and inefficiencies. It’s a house that Lynch fans will want to consider in conversation with the architecture of Fred and Renee’s house in Lost Highway. And I especially like this connection because within Tati’s mostly light humor regarding the Arpel house, there’s also an eeriness that comes through in a night scene where Madame and Monsieur Arpel gaze out of two round upper story windows and take on the appearance of eyeball pupils, thus making the house seem alive and watching. In the Arpel’s front yard is a fish-shaped fountain positioned perpendicularly so a blue-hued water sprays straight up out of an open mouth that looks almost exactly like the one in Hulot’s market bag.

What makes the fish fountain funny is that Madame Arpel keeps it turned off unless a visitor pushes the buzzer at their streetside gate. Then she quickly turns it on, as if to impress the outside gaze that’s about to enter. Here’s where sound comes into play. The fountain is extremely loud, so it’s absurdly obvious to any visitor that it’s just been turned on. In fact, a number of scenes show people startled by the sudden sound of the water splashing down into the pool around the fish. Still funnier is the sound of the fountain being shut off. As soon as Madame Arpel hits the switch, the upward stream diminishes but before it quits there’s always three or four gurgle and gasp noises as the fish appears to burp out a few last spurts of the blue water. As a metonymy for modern efficiency and style, the fish fountain sounds like it’s always on the edge of a catastrophic collapse–so the very facade of the Arpel’s image of themselves is also teetering at the brink of breakdown. Through the fountain, Tati creates the complicated dynamic of surrealism, physical humor, and threatened family identity. In Mon Oncle, this dynamic functions within a comedy mode, and in Twin Peaks a similar dynamic is conjured but in a way that transcends standard taxonomies of genre.

Speaking of houses, Monsieur Hulot’s apartment building is used by the film to distinguish his carefree character from Monsieur and Madame Arpel’s–and it’s Hulot’s obliviousness to the drive to efficiency and consistency and socially-established style that makes him so appealing to young Gerard, who desperately wants to have some fun and mystery and spontaneity in his life. In contrast to the symmetry and efficiency of the Arpel house, the apartment building where Arpel lives has a wonky design as if each story was an afterthought that got stuck on in random fashion to the ones below it. More than once the film grants quite a lot of film time to showing Hulot enter at the ground floor and then appear in various windows or open-air stairwells as he must zigzag left to right and back again on his ascent to his top-floor home.

En route, Hulot encounters neighbors, sometimes having to navigate awkwardly as they pass each other in narrow spaces. The notions of home and of the nuclear family embodied in the architecture of this building and how we observe the diverse residents moving through the wonky design are a world apart from the Arpel’s world. Young Gerard is the character who sees both worlds and considers them as he, like most children, process experiences to formulate their ideas about what to value and aspire to. His uncle Hulot is an adult who still operates with all the joys and flexibilities that Gerard feels, yet there’s no denying that it’s his parents’ love and approval that he most deeply seeks. In light of this, Mon Oncle attunes Twin Peaks viewers to the child-parent relationships throughout the series and prequel film (and the books for those who include those in their idea of Twin Peaks canon). Consider the Twin Peaks children we know: How do those with parents relate to other adult role models as they try to negotiate parental love and approval and what about those without parents? And what roles do surrealism and humor play in the answers to these questions?

In addition to the houses, there are so many other sequences of wonderful humor that connect well with Twin Peaks. At one point the Arpel family hosts a weekend party and things fall apart–it’s something like if you could drop Jim Carrey into Bunuel’s The Exterminating Angel. The weirdness of conversations around the dinner table being anything but lively, or even just normal, is played to its full in the scene. Hulot is radically out of place in this scene where all the other adults are clearly trying to perform a dinner party through their understandings of shared social decorum. Hulot is oblivious to decorum. He’s not actively undermining or resisting it; he’s just goofily clueless. That said, the other guests are not great thespians of decorum even though they’re really trying. The men can only put forward production statistics from work and the women can only remark on Madame Arpel’s mechanized kitchen. In Mon Oncle this strain opens the way to laugh after laugh–it’s a truly spectacular and sustained sequence–and it’s easy to see how a sequence like this may be among the sparks that ignite Lynch scenes from the blood-bubble-blowing chickens at the awkward dinner in Eraserhead to the backyard barbecue in Inland Empire and so many strange meals in between like dinner at the Haywards when Leland launches into “Get Happy.”

One more comedy scene of Twin Peaks note comes very near the film’s end. Monsieur Arpel and Gerard are dropping Hulot off at a transit station. Arpel has secured the uncle a job at a provincial branch of the Plastac factory because he considers Hulot a bad role model for Gerard and wants him away. Arpel no doubt truly considers Hulot a bad role model, though whenever he says this to Madame Arpel (Hulot’s sister, of course), she suggests he’s just envious of Gerard’s attention to Hulot. The transit station embodies the crowds and fast pace of modern life. Tati uses the soundtrack to underscore the tempo, and the status of the music grows ambiguous–diegetic or non-diegetic–as the movements of the people on-screen synchronize with its rhythm. It’s an orchestrated comic comment on the intensity of modern life that doesn’t speak at all to Hulot. It’s also a scene that resonates nicely with the scene in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me when Bobby walks backward away from Laura and Donna in front of the high school and “A Real Indication” by Thought Gang joins the soundtrack and suddenly everyone around Bobby is matching motion with the beats. Lynch’s scene uses a similar cinematic brilliance of technique but without an obvious social commentary behind it.

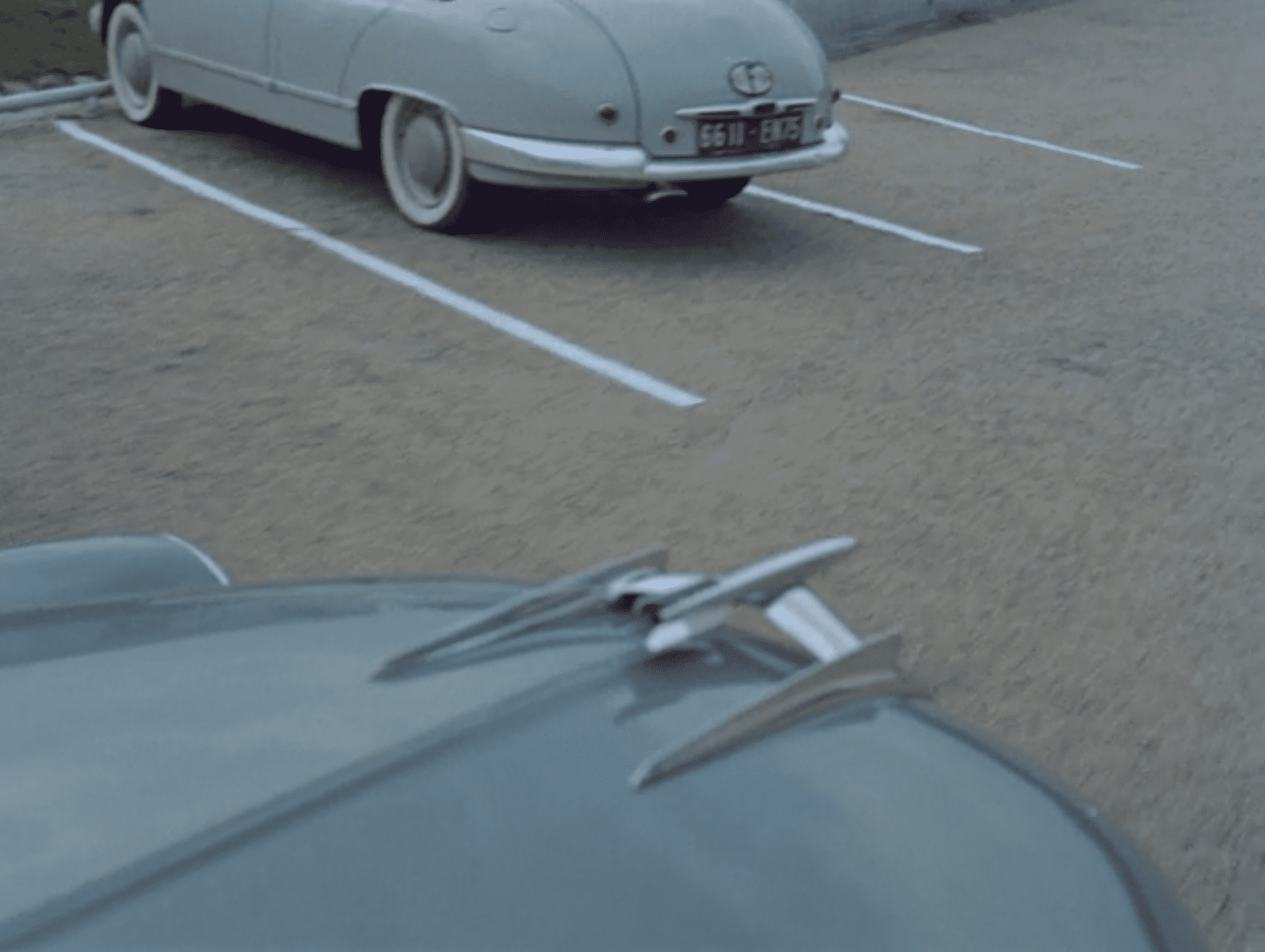

I’ll close this consideration of Mon Oncle with a bit of a shift from its humor. The contrast between Hulot the uncle and his sister’s family is reflected in the cityscape of the film. The film opens and closes with images of parts of the city being deconstructed to make way for new modern buildings more suited to the new way of life and productivity. In fact, the opening credits appear printed on physical signs at a construction site, putting the film into play as an object that is both an industrial product and a work of art–an artifact of tension. Shortly after the credits, the camera’s mounted on Monsieur Arpel’s car such that his rocketesque hood ornament claims a large amount of screen space as he navigates his way to the Plastac factory parking lot. Then, just behind the factory the camera captures a horse cart–a mode of transportation that appears time and time again in Mon Oncle.

It’s a perturbing coexistence of eras–the coexistence of what cultural critic Raymond Williams has called the residual, the dominant, and the emergent. A variety of technologies that point to eras in the past, that attest to the mode that dominates the present, and that cast shadows backwards from the futures to come. Such coexistences signal the inconsistencies of life. Hollywood and other cinemas following suit aim for consistencies to streamline the engagement they ask of the spectators. But Lynch, like Tati, demands more from spectators, and he does so by putting on-screen the coexistence of eras that more nearly resembles the bewildering experience of being alive. Just think of all the telecom devices in Season Three of Twin Peaks, then think of the eras of telecom devices to which you’re connected in your own life, from your parents’ or grandparents’ landline phones to the Huawei smartphones of your colleagues to a government office fax machine.

And, finally, along the arc of Mon Oncle, there’s a man sweeping detritus from the street, or always at the edge of starting his sweeping. If someone were to do a history of sweeping in cinema–and you’d have to include Chaplin in City Lights–Tati’s film would be a vital entry as would the polemic Roadhouse scene in Part 7 of Season 3. And that history might take as its epigraph an excerpt from David Lynch and Kristine McKenna’s memoir/biograph where Jack Fisk said, “At some point I went home to Alexandria and found David working in an art store, sweeping–David’s a great sweeper…He still likes to sweep, and takes great pride in it.”