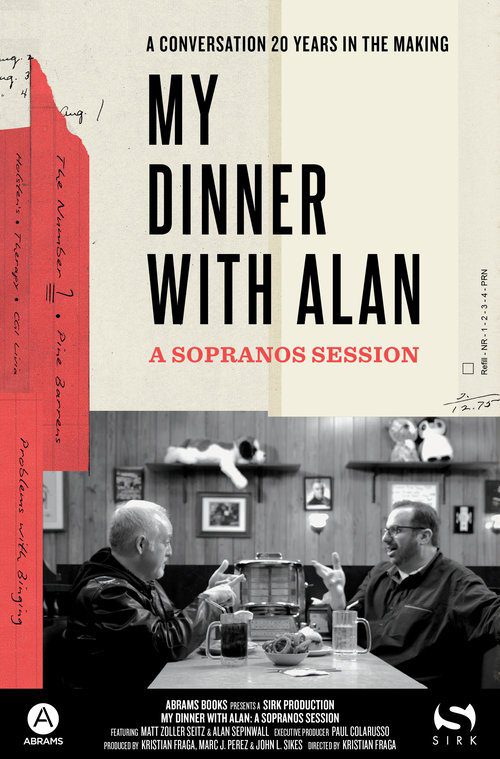

I had the pleasure of attending the World Premiere of My Dinner with Alan (directed by Kristian Fraga) during The Sopranos film festival at IFC on the evening of January 11, 2019. The film consists of a conversation between critics Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall located at Holsten’s Diner—the location of the infamous final scene of The Sopranos. The two primarily discuss the show and their experiences covering it; both for the Star-Ledger as it was airing, and in their new book The Sopranos Sessions. But their conversation moves in the direction of the more philosophical at times; or least the sociological as it relates to the state of television.

The title of the film is a clear reference to My Dinner with Andre, and its opening scenes—featuring Seitz navigating airports to travel to New Jersey to meet Sepinwall—couldn’t help but make me think of Wally riding the subway to meet Andre.

Of course, My Dinner with Alan is not nearly as deep as Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory’s masterpiece, but it doesn’t make any pretension to be. Instead of a fancy restaurant as the setting, this is a diner where they eat onion rings like the Soprano family, Seitz enjoys some Taylor Ham, and the two spend most of their time talking about one of the best shows to ever grace our screens. Could that have fed into a discussion of Martin Heidegger? Sure, but it is perfectly fine that it didn’t.

It was similar to its namesake insofar as what one might think would be boring—watching two people eating and having a conversation—wasn’t at all. When My Dinner with Alan ended, I found myself wanting more. Luckily I was in a position to receive it, as Sepinwall, Seitz, and Fraga were on hand for a panel discussion after the screening. In what follows, I will offer some thoughts about the film and the discussion that followed, noting when something is from the latter.

After arriving to Holsten’s and ordering the aforementioned onion rings, Seitz and Sepinwall settle into a conversation about The Sopranos that lasts for about an hour. There are anecdotes about personal interactions with James Gandolfini not understanding press events, reading a children’s book, and possibly thinking about walking away from the show after the third season because he “couldn’t get the stink” of Tony Soprano off him no matter how much he showered. This led Seitz and Sepinwall to discuss the question more generally as to whether an actor can make a separation between themselves and the character they portray, particularly when it is for as long as Gandolfini was Tony. (N.B. This last bit about “washing the stink off” was during the discussion panel; not the film).

It also fed into a discussion of death—the death of James Gandolfini in real life, and how that tinges a present viewing of the show, but also the impact of the deaths in the narrative that we now all know are coming. They hit just as hard on a second, or third, or fourth viewing as they did on the first, or perhaps even harder. The first time through The Sopranos one is caught up in thinking about what is going to happen. Further viewings lead one to dwell with the how and why.

Apparently David Chase originally conceived of the show as a sort of live-action Simpsons, but Gandolfini made Tony so human that it altered what the series would be. The show’s brilliance then wasn’t just a matter of Chase’s genius (if the term brings to mind the one who is source of a novel/meaningful artistic creation) but his adaptability in the light of circumstances. It is further a testament to the way in which The Sopranos wouldn’t be The Sopranos with a different lead: James Gandolfini simply is Tony. There could be no substitute.

And as much as The Sopranos opened the door for what gets called the current “Golden Age of television,” it is also inimitable. As Sepinwall notes, yes, it inspired any number of shows we could list, but none of those shows are it; none of them quite do what The Sopranos managed.

Perhaps this is, at least in part, due to how we view things nowadays, both in terms of the literal (i.e., the means by which one views a show) and the figurative (how does the collective “we” view the notion of paying close attention to a media product, thinking about it, discussing it, and perhaps even writing about it). As we move to an era ever more defined in terms of streaming services (it’s hard to believe that Netflix only started offering such in 2007), the way we consume things seems to be moving in the direction of the binge-model. Rare is the show one watches week-to-week, if it is even released that way. After watching the first episode of the second season of Westworld, for example, I decided maybe I would binge the rest sometime later (which I still have not done).

This means that we tend to be watching things at different times, in a way that erodes the possibility for conversation about them. Further, Seitz and Sepinwall note how the very pace of the binge watch tends to collapse the space for thinking, insofar as that involves rumination. Something different happens when one has a week to digest an installment; to mull it over and pass it through multiple stomachs. This doesn’t quite land in “get off my lawn” territory, as the two seem to recognize the possibility of a Netflix show being as meaningful as something like The Sopranos; yet they also note that it probably would not also be as popular.

Seitz mentions Tony’s famous line about coming in at the end, and the sense that this was true. Perhaps it was originally about the end of the 20th century, and a worry about the death of American dominance, that sort of thing, but the feeling has gotten if anything all the more pervasive. Chase starts to feel like Cassandra, foretelling a doom we’re unable to avoid.

There is a famous notion in Hegel about the “end of history”—his whole story is about its dialectical developments; a back and forth, for example, between abstract moral universality and concrete ethical substance. If we take the end to be a goal, then this would be to stop that movement and its concomitant “slaughter bench” in order to achieve a harmonious society, or world. Some, like Francis Fukayama in 1989, seemed to think that we were achieving that goal through the spread of global capitalism, or the neoliberal order. Now that seems clearly false. Yet, what if we take the notion of the end of history in a more pessimistic way? What if history has stopped because everything is now on one flat surface and no overarching narrative can unify it? What if now, instead of dialectical development, all we have is dispersion and fracturing? Each can have what they want, in separation from one another, but nothing could bring us together as a whole. This thought, too, strikes me as Hegelian, though in a far more tragic register.

To be clear, though, Seitz and Sepinwall do not talk about Hegel. They do, however, hit on questions pertaining to therapy, or psychoanalysis. Seitz claims, for example, that part of what makes The Sopranos so great is the way that it understands therapy, differing modes of therapy, and dramatizes things like repression, transference, etc. And I have to agree with that.

During the discussion panel, it came out that a certain TV executive the show was pitched to wanted the psychiatric aspect taken out. But The Sopranos wouldn’t be The Sopranos without it. I went so far, when the show ended, as to argue that the real ending was/should have been when Tony quit therapy. In part that’s because I wasn’t very keen on the final scene (I have since come around), but I still think I had a point. This is, after all, how the show begins: with Tony having a panic attack and beginning to see Dr. Melfi. So isn’t when he quits the natural place to end?

Seitz and Sepinwall of course discuss that final scene in this film that is set in its location; what they thought at the time, and what they think now. Another version of that discussion, cribbed from The Sopranos Sessions, was published the other day. Sepinwall originally thought it was about putting the audience in the mind of Tony; paranoid about the possibility of imminent death. But, as Seitz notes, there is nothing in the content of the scene to suggest this: Tony seems fine and happy to enjoy some Journey and onion rings. I rather enjoyed his thought that it was a matter of Chase “whacking” the audience, but ultimately I think that both Seitz and Sepinwall are right to move in the direction of something a bit more thematic. We aren’t shown whether Tony dies, but what is going on is about death, in one way or another.

My position has always been that he doesn’t die because we weren’t shown that. The text is the text, and it just cuts off. The show ends with an ellipsis, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t worth thinking about the question, and Seitz and Sepinwall certainly provide interesting ways of doing so.

It’s not about explaining what happened in some definitive, or irrefutable way, but about interpreting it in the sense of entering in between competing possibilities and selling a certain way of thinking. You don’t have to buy it; perhaps you, like me, enjoy window shopping, which in this case means thinking, but you can’t sell me on something that is not on display. I appreciate that, despite Sepinwall’s apparent flirtations with the “Tony is dead” reading of the ending, he and Seitz ultimately both seem to recognize that the point is more in the space of ambiguity.

It’s that working out of nuance that leads me to recommend My Dinner with Alan, and The Sopranos Sessions book. If you’re a fan of the show, I can hardly think of better sources to get you thinking about it.

Here’s a theory: there are two times in the show when the lights go out. The first occurance is when Tony assumes his place as the boss. He shows up at night Dr. Melfi’s office and the power goes out due to a storm. The family ends up eating together that night at Vesuvio. The other ellipses comes during another storm when the family gathers for dinner at Holstens. I assume that night, when things go black, its the end of Tony’s reign.