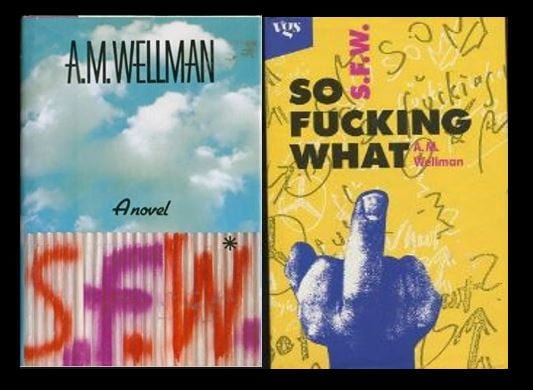

If you were in a mall bookstore in 1994, say a B. Dalton Booksellers or a Waldenbooks, you might have noticed a hardback spine, bright blue with clouds. There would only be three letters to the title in spray paint, pink font: “S.F.W.” The author’s bio would read as A.M. Wellman winning a Playboy College Fiction Award. The title stands for “So Fucking What.” Scanning the summary, you would read references to Heathers and Dog Day Afternoon. A blurb on the back compared the main character Cliff Spab to Bart Simpson at twenty, and it was “soon to be a major motion picture.”

This is the novel adapted for the 1995 film. Yet, the novel reads incomplete. As a Goodreads comment by “David” reads, ” Despite the fact that the publisher took the rough draft Wellman had put together after winning a Playboy contest for “The Madison Heights Syndrome,” tossed on a title and cover, threw it out into the world before it was finished, made a movie, and all that shit, this book has an incredible beauty to it.”[1] It all but ruined 21-year-old Wellman’s writing career before it even began. That is to say, Wellman’s novel wasn’t quite what publishers were hoping for in comparing young author phenom Jay McInerney and his Bright Lights, Big City.

Still, the movie was put into production a short three years after the publication of its source material. The movie is considered better than the book but maintains a 12% Rotten Tomatoes rating. Still, it is at least this author’s view that there is some value here, and I think there are a handful of ways to parse it. I would even go as far as to say it highlights some extremely important questions that remain relevant, perhaps even heightened today. It doesn’t hurt that Stephen Dorff has had a loudly applauded and welcomed come back with True Detective Season 3.

The credit sequence that opens the film is accompanied by Soundgarden’s “Jesus Christ Pose” and from the start, it is worth noting that this film’s soundtrack falls into a category of essential 90s grunge movie soundtracks along with Singles, Clerks, The Crow, and Lost Highway, to name a few. If you aren’t familiar with the lyrics, a quick read or listen will tell you that the choice of that particular song establishes a self-aggrandizing martyr, a poser. And as much as it speaks to that character, it’s also speaking to those who so badly need to believe in and drain that character. It was a unique time for that particular book to be adapted.

The book was published the same year as Douglas Coupland’s Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture and Don DeLillo’s Mao II. The movie, released later, mid-decade, comes with a soundtrack that perfectly reflects the grunge, “I’m a loser, baby,” attitude of that year along with its characters’ reactions to their environment. The “generation” was still seeking validation in their mourning of Kurt Cobain. A commonly posed question to teenage peers and a response “Did you genuinely cry when Kurt died?! I did.” And then the classic “Kurt Cobain the voice for our generation?! He didn’t speak for me.” Cliff Spab and Wendy Pfister are their own 90s archetypes. They are the couple for the 90s that were survivors of the violence perpetuated by filmic power couples like Mikey and Mallory. As the novel’s character would have it: “Me! Cliff Paul Spab. The guy Time magazine calls ‘a leader of the dark side of the Pepsi Generation’.”[2] They are Generation X—exploited, cashed-in, and as quickly forgotten, relegated back to their latch-key roots. Spab notices this immediately. Even his parents are oddly invested in him with his new-found fame from the time he opens his eyes in the hospital, but let me rewind. By the way, S.F.W. premiered January 20, 1995, and was released on VHS that same year, so I think I can get away with that verbiage.

Comparing 1993 film Lipstick Camera to the intentions of S.F.W. in Sight and Sound, Mark Kermode says “… treads a fine line between having potential and being pretentious.” But it’s not pretentious to have a message, though we can revisit successful communication of that message. Both Coupland’s Generation X (yes, that’s where the name comes from) and Wellman’s S.F.W. had cynical but genuine nuclear anxiety. In Coupland’s, it was expressed in character Dag’s storytelling obsession of “Mental Ground Zero: The location where one visualizes oneself during the dropping of the atomic bomb; frequently, a shopping mall.”[3] In S.F.W., five unsuspecting convenience store shoppers are taken hostage by panty hose-masked, anti-nuclear bomb activists, SPLIT IMAGE. In the film tension is built by the masked men’s diligent silence; they are not silent in the book. Actor Jack Noseworthy plays Spab’s comrade in disaffectedness, Joe Dice. The year previous, in 1994, Noseworthy was the lead in MTV’s Dead at 21, a series about a kid who at 20-years-old realizes he is a living experiment whose genius is due to an implanted microchip that will kill him by twenty-one. So translated, maybe it’s better to be dumb and truly live than be brilliant and dead before you can legally purchase beer. His casting feels intentional here. Live before the big bomb hits.

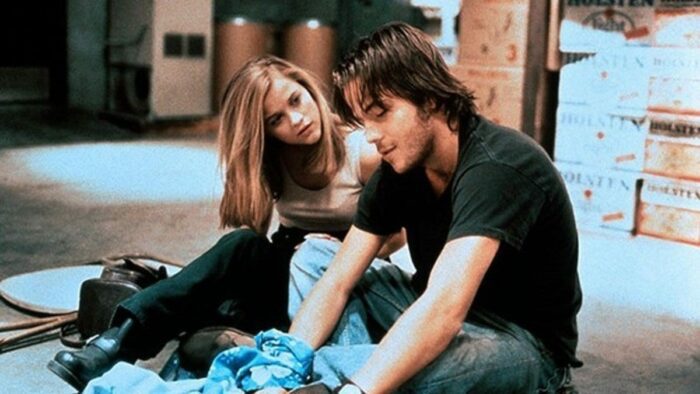

The point that comes up is one of many attempts to understand the Generation X mentality. Basic encyclopedia entries will frame the post-baby boom generation as being born from the early ’60s to around 1981. They were the “latch-key kids” steeped in Cold War paranoia and targeted by content marketing, and it’s the marketing of this generation’s need for validity that gets exploited and explored through films like Reality Bites, Singles, Empire Records, Suburbia, as well as S.F.W. To quote Moore of Mel speaking to the 25th anniversary of Reality Bites, “Brands weren’t people yet and people weren’t brands, and we were absolutely smugly self-serious and precious about our identities.”[4] The movie makes a distinct departure from the novel in character Wendy Pfister. In the novel, she is caught in the convenience store with three ounces of weed to distribute back at her high school, meaning she and Spab are coming from the same backgrounds. In the film, she is from an upper-middle class household, and her relationship with Spab, cultivated in a terrorism scenario, highlights the generation’s common ground between socioeconomic classes. When forced to face tragedies or terror, they respond the same: “So fucking what?”

Spab and Pfister’s conundrum is this. They have been hostages of domestic terrorists for 36 days with cameras pointing at them, broadcasting their desperation across America’s airwaves, and they will suffer a second victimization in fame. Cliff and Wendy barely escape as Joe is shot and killed after completely breaking down in a violent escape attempt. The other hostages were already executed. When Spab wakes up in the hospital, separated from Pfister, he is surrounded by his greedy parents, who have negotiated book and movie deals, by journalists sneaking into his room for inside scoops, and by investigators suspicious of his involvement—he must have orchestrated his newfound fame. His apathetic slogan, “so fucking what,” has inspired audiences. No one sees the futility of his desperate pleas and their lauded welcome more than he.

Gone rogue from his family’s attention, he journeys through a cast of characters, who want more of him than he has to offer. In a piece written to praise Clerks for Entertainment Weekly, Glenn Kenny frames it as such: “… Spab is confronted by so many obnoxious caricatures that you keep waiting for the caption reading “Satire” to pop up, but it never does.”[5] Include in that cast a young Tobey Maguire as a stoner and Jake Busey. As Spab navigates the varying levels of their needs and greed, he is forced to reflect on his own attitudes and needs. At the “Burger Boy,” his previous place of employment, he has been made employee of the month, which infuriates him when he recognizes that no one cared about Joe. In a scene that pretty much defines the main point of the film, Spab walks unnoticed into a record store accompanied by Radiohead’s then-new song “Creep,” where he watches over an audience glued to an endcap playing his hostage footage like a best-selling movie. The scene they are watching is his title-selling speech. The same expletive-riddled speech from the book is as follows.

Spab: So I might die in here. So fucking what? So I haven’t had a shower or any decent food in too fucking long. So fucking what?

Pfister: So what are you trying to say?

Spab: I’m saying, how is this any different from anything else that’s happened in my life? God, when I was in high school, fucking up big-time, and people were giving me a bunch of shit, all I ever said was, so fucking what? When I was still getting minimum wage at that goddamn Burger King even after working there three years, well, so fucking what? Jesus Christ, that’s all you got to do is just say to yourself so fucking what and, believe me, it works wonders. Trust me.[6]

With distance from the situation, watching the audience take in his desperate words as inspired or profound appals him. And without so much as a thesis, I think we can dive deeper here, somehow contextualize this at almost 25 years later. So let’s ask the question, “So what?” I spared you one expletive.

Has it lost its relevancy? Did it ever have it? My case for then is that the statement it made about the desperateness of a generation who was then and continues today to be silenced and ignored, except when corporations needed their audience and money, was relevant. Per today, only this week, we saw yet another incident of domestic terrorism. A quick Google search already presented this quote: “Gun rights advocates posted support on social media Thursday for students who walked out of a gun-control rally in anger and tears over concerns the event inappropriately politicized their grief.”[7] They are calling them Generation Z now, right? I suspect they will have their own S.F.W.s in literary and filmic production. In the past week, I have seen articles of media exploiting victims’ tears and articles telling us that these victims are capturing the violence on their own phones, though we never see their footage reported. Researchers Chermak and Gruenwald in a paper titled “The Media’s Coverage of Domestic Terrorism” tells us that in case-related data on 2,685 homicides between 1983 and 1996, “… only 40 per cent of the homicide incidents actually received news coverage, that victim and case-related variables are significantly more important than suspect variables …”[8] This is to say that victim narratives are important. I think S.F.W. portrays a generation that felt invisible in an environment that felt over-saturated in commercialism and hungover from Cold War paranoia, unable to see how domesticated that paranoia might become with Columbine and later 9/11. Millennials have likely felt overexposed in an even more overwhelming environment born of infotainment “news” that began with OJ Simpson’s car chase and unending after Facebook and Twitter. Eyes are now on Generation Z, who are having to become their own “heroes,” in their under-siege classrooms.

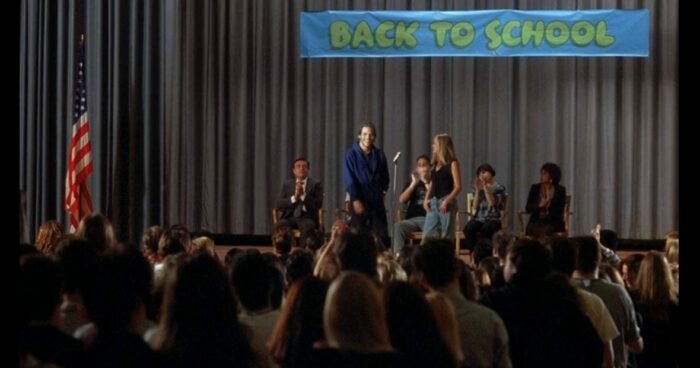

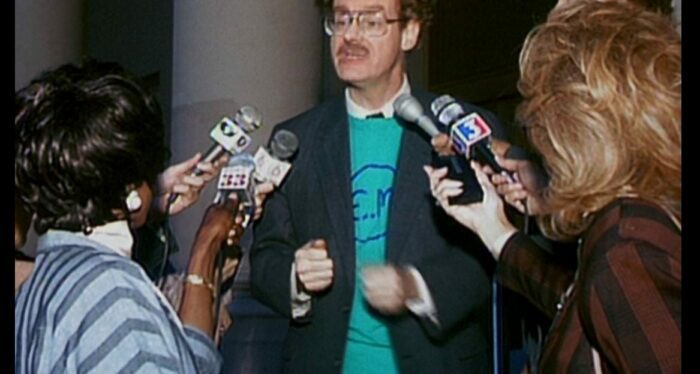

But S.F.W. has one more message for us. Spab and Pfister finally end up together. They begin sharing their stories at high schools when shots ring out. The perpetrator is a stereotypical plain-Jane—in a plain sundress and with book worm glasses, likely invisible to her fellow students—while Kenny describes Spab (Stephen Dorff) and Phister (Reese Witherspoon) as “the cute white girl and the even-cuter white guy.”[9] She yells out the antithetical message to counter Spabs. E.M., “Everything Matters.” Spab and Pfister laugh, watching her become the new interviewed celebrity as they happily fade back into invisibility from their hospital beds.

But doesn’t that sound eerily familiar when we think on the “Black Lives Matter” movement and the absurd counter retort, “Every Life Matters?” As German Lopez explains in his article for Vox “Why you should stop saying “all lives matter,” explained in 9 different ways,” “… a better way to understand Black Lives Matter is by looking at its driving phrase as “black lives matter, too.” So all lives do matter, obviously, but it’s one subset of lives in particular that’s currently undervalued in America.”[10] Without journeying down that rabbit hole, here is my point. S.F.W. is a film and literary work that can help us contextualize issues that were absurd then and are, perhaps, doubly absurd now. So, at hand is not Bart Simpson at twenty but America 25 years later. We need to consider the “E.M.” students, the marginalized students who feel obscured by media portrayals. We need to pay attention to undervalued lives, and we need to look at a generation over-saturated by infotainment, news, commercialism, political statements, and resurfacing Cold War fears, fighting back the urge to simply say “so fucking what?” For some of us, we need to stop and remember how we felt then. Now that I’m 25 years older, having watched this as a teenager myself, I’m ready for some new material. Generation Z, I’m counting on you, and you matter.

[1] David, “I almost refuse to write a review …” Goodreads, Retrieved May 13, 2019 from https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/2076980.S_F_W_?from_search=true

[2] Wellman, A.M., S.F.W. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), p. 79.

[3] Coupland, Douglas, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), 63.

[4] Moore, Tracy.

[5] Kenny, Glenn. 1995. “Great Xpectations.” Entertainment Weekly, no. 275 (May): 68.

http://search.ebscohost.com.lib-e2.lib.ttu.edu/login.aspx?

direct=true&db=fah&AN=9505177671&site=ehost-live.

[6] Wellman, A.M., S.F.W. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991), p. 145-146.

[7] John Bacon and Trevor Hughes, “Students walk out of Colorado school shooting vigil, saying their trauma was being politicized,” USA Today, May 9, 2019, Retrieved May 13, 2019 from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/05/09/colorado-school-shooting-vigil-students-walk-out-protest/1150282001/

[8] Chermak, Steven, and Jeffrey Gruenewald. “The Media’s Coverage of Domestic Terrorism.” Justice Quarterly : JQ 23, no. 4 (2006): 433.

[9] Kenny, para. 4.

[10] Lopez, German, “Why you should stop saying “all lives matter,” explained in 9 different ways,” Vox, July 11, 2016, Retrieved on May 13, 2019 from https://www.vox.com/2016/7/11/12136140/black-all-lives-matter