“What is a ghost?

A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again?

A moment of pain, perhaps.

Something dead which still seems to be alive.

An emotion suspended in time.

Like a blurred photograph.

Like an insect trapped in amber.”

These are the opening voice-over words of The Devil’s Backbone, a film directed by Guillermo del Toro, released in 2001. It is the second film of a trilogy which also includes the director’s first feature film Cronos (1993) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006)—the latter having so much in common with the subject of this review.

What especially attracts me to del Toro’s films is the magical, fantasy world intertwined with the ordinary, everyday life, as if they were different layers of reality. This is especially true for this trilogy. On the surface, there is the ordinary world with its rational problems, sometimes combined with political or ideological struggles, as in The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth. In parallel exists a fantasy world which mirrors the events of the ordinary one, sometimes even explains them revealing the inner logic of things. Everything true for the former is true for the latter too but on a more intimate, maybe subconscious level.

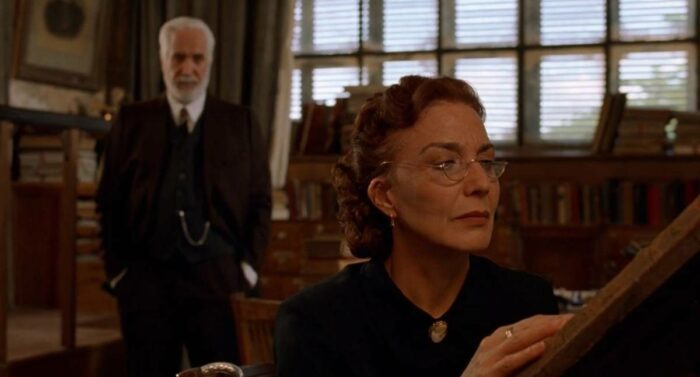

Set in 1939 Spain, at the end of civil war, The Devil’s Backbone tells the story of a 12-year-old boy, Carlos (Fernando Tielve) who is left by his guardian in an orphanage. Nationalist forces have killed the boy’s father. The orphanage is located in a desert-like place, far from any inhabited area, and is run by Carmen (Marisa Paredes)—the widow of a leftist, and Dr Casares (Federico Luppi). At the time of the events of the film, the orphanage is practically a shelter for leftists’ children, as Carmen expresses they are “Reds looking after Reds children”. It is also revealed that they are hiding gold for the leftist Republican forces.

I don’t really want to go into political analysis here, being that I am more prone to uncovering symbolic meanings than interpreting political processes—especially as I’m not very knowledgable of details of the Spanish Civil War. I’ll only mention that these two incarnate the challenges faced by leftist intellectuals of the time. Casares’ impotence could be a representation of the weakness of his (as well as Carmen’s late husband’s) idealistic principles and their inability to put their ideas in practice. Carmen is missing her right leg and wears a prosthesis to “stay on her feet”, though it hurts, unbearably sometimes. This makes me think of broken balance and lack of faith in the future. She has to use whatever she’s got, however imperfect it may be, to maintain the balance. Neither Carmen’s husband nor Casares’ ideas have been able to give her real support.

And that’s probably why she needs Jacinto (Eduardo Noriega), who has been raised in this school and now works here as a caretaker. He is in a sense, the opposite of Casares—he is pragmatic and has always been interested more in the physical than spiritual. He hates the school, desires to destroy it someday, and the only thing he cares about is how to get to the gold kept hidden in the school. What exactly influenced the development of his personality is unknown, we only get hints about it. One of them is an old photograph of Jacinto with his parents. “How lonely, the prince without a kingdom, the man without warmth”—these words are written on the back of the photo, apparently by Carmen. Jacinto is the main antagonist of the film. He is destructive, violent, and greedy; everything he does is selfish. It’s not surprising that boys are afraid of him.

All that I said above is related to the adult’s world, which is rational and logical, but as I already mentioned, there is also another—a fantasy world. And it seems that this world is accessible for children only. Soon after arrival, Carlos sees the ghost of a boy; children call him “the one who sighs”. Although only children see or hear the ghost, he can interact with reality; for example, he knocks over a jug of water.

Another extraordinary (or at least strange) thing—actually the first thing Carlos sees upon his arrival—is a bomb stuck in the ground in the courtyard. It fell during the bombardment one night but didn’t explode. The bomb has been deactivated and left as it is. Children play around it, even decorate it with different colored ribbons: red, yellow, purple (the colors of the Spanish Republican Flag). This bomb is a perfect example of two worlds intertwining. Located in the center of the schoolyard, it is central for the story as well, serving as a link between different layers. Besides being a constant reminder of the war, I see it as a symbol of overwhelming emotions that have to be kept unexpressed, “emotions suspended in time.”

There is a subtle connection between the bomb and the ghost. The night when the bomb fell, one of the boys, Santi, went missing, and the same night, the ghost appeared. Gradually, we learn about the connection between Santi/ghost (Junio Valverde), Jacinto, and the oldest of the boys, Jaime (Íñigo Garcés). Terrified of Jacinto, Jaime at the same time becomes more and more like him—bullies other boys, including the newcomer Carlos, the loneliest of them all—relying only on himself, keeping his fear, anger and sadness inside until he finds the courage to face his fears and leads the boys against Jacinto.

The secret connecting Jaime and Jacinto, with its hidden, unexpressed emotions, is incarnated in the unexploded bomb, and at the same time, this secret ‘creates’ the ghost. I could even say… well, metaphorically… that Jacinto creates the bomb (he actually does later set off an explosion), but Jaime is the one who keeps it unexploded (also metaphorically speaking). Although bomb has been deactivated, Jaime believes that it’s live and if one puts an ear against it, ticking can be heard. Thus, the bomb is, as the ghost, “something dead, which still seems to be alive.”

I cannot leave out a crucial scene that reveals one more fascinating analogy. This is the scene where Casares shows Carlos the “devil’s backbone”; an underdeveloped human fetus with an exposed spine kept in a jar full of reddish yellow liquid. Casares calls the liquid “water of limbo”. According to common superstition, these are fetuses of children that shouldn’t have been born, or “nobody’s children”. (This superstition, interestingly, includes “positive” belief too: the liquid in which these fetuses are kept is used to cure various disorders, including impotence.) But there is another, actual water of limbo in the basement: a pool of similar colored water, where Santi and his ghost are kept in limbo, as turns out later—waiting for revenge.

Carlos becomes the key figure in revealing and resolving school’s dark secrets. Is it because of his personal sincerity and courage? Or perhaps being a newcomer not burdened with school realities also helps? I think it’s both. After several encounters with the ghost who frightens, and at the same time, fascinates him, Carlos overcomes his fear and offers help in whatever the ghost’s desire is. Santi asks to bring Jacinto to him. So he does. A scene at the end of the film, where the boys armed with wooden sticks attack Jacinto, might remind the viewer of an earlier scene in the class where Carmen shows them the picture of the Ice Age hunters attacking a mammoth, telling them that, “in those days men had to act in groups”. Jacinto is stronger, as was the mammoth, but the boys have a numerical advantage, and they work in a group now, which allows them to defeat him. Is it cruel of the boys to lure Jacinto to the basement and throw him in the pool where the ghost awaits him, or is it fair justice? Again, probably both.

The Devil’s Backbone is a coming of age tale about boys living in a cruel world, the world where ghosts can be less scary than living people. In the final scene, the boys are leaving the orphanage heading towards the future, leaving the spirits of the past life behind. But if the ghost is “a tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again” then life must be continually creating new ghosts waiting for someone brave, full of sincerity and kindness, to reveal their dark secrets and let them rest.

Great article, perfect analysis by author, it’s looks like she fill perfect the structure of dramaturgy build by genius Guillermo del Toro.