The alien is the other. The term does not directly refer to beings from outer space. If we have moved away from it when it comes to immigrants, it is because it has a pejorative connotation precisely insofar as it emphasizes alterity. To call a human being an alien is to label them as not one of us, and this risks thinking of them as not (fully) human.

But, of course, it seems to be a natural tendency for us to engage in such tribalism. Even with all of the historical progress we have made in terms of thinking about human rights, and so on, we’re seeing it rear its ugly head again. Children are being separated from their parents; ICE is throwing people in solitary because they are gay, or trans, or disabled. But underneath all of that is the thought that these people don’t count because they are other.

Ridley’s Scott’s Alien succeeds by forcing us to confront radical alterity in the form of the xenomorph. It is horrifying: a being that bears such little resemblance to us. Its blood is acid. Its biological basis is silicon instead of carbon. And its whole modus operandi makes virtually no sense from a human perspective.

What is it doing, for example, with Dallas (Tom Skerritt) globbed up against the wall?

At this point I should perhaps note that I am considering the original film on its own, uninformed by any context or knowledge provided by further entries in the series. I think it is more powerful that way, and as much as I can enjoy the other films, they risk undermining the force of the first.

Alien is a horror film; Aliens is an action thriller. And, frankly, the more the mythos of this world got built, the less I liked it. Red Letter Media basically portrayed what it was like for me to watch Prometheus.

But I don’t want to debate anything of that; rather, I want to focus on the first film and the source of its horror, which was one alien. One was enough, as it seemed both inexplicable and unstoppable. The xenomorph is utterly alien, but clearly intelligent, as she sneaks onto Ridley’s escape vessel, for example.

And I have always thought of the alien as feminine, and that the crew consistently misgender her. Perhaps this is a mistake, however, and it would be better to view the xenomorph as outside of the gender binary we are familiar with. This might fit better with the way I intend to suggest a symbolic deconstruction of phallogocentrism in the film.

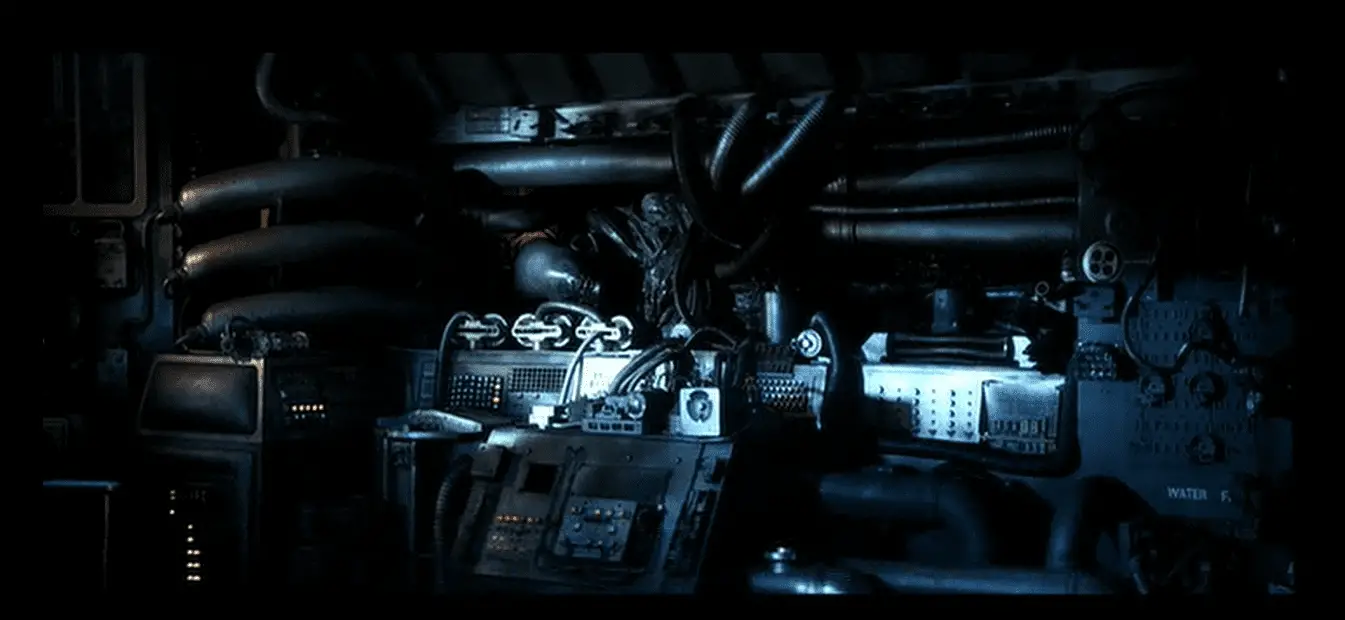

Yet, without intending to be superficial, some of the images in the film have always seemed to me as strikingly reminiscent of female anatomy:

And this tracks with the overarching theme of the alien as other. We live in a phallogocentric world, after all, structured by a model of thought as reason intimately connected to a masculine image of power. Just think of the phallic nature of our monuments, or the men who want to mine the Moon.

This is what installs the binaries, however: masculine/feminine, good/evil, etc. It’s black and white thinking across the board of various conceptual terrains in line with the strict dichotomy: either you have a penis, or you don’t.

This is what led Sigmund Freud to characterize women as primordially castrated, and Simone de Beauvoir, from the opposite point of view, to suggest that Woman is not determined as the polar opposite to the positivity of Man: she is both the negative and the neutral. It is fundamentally what is not-Man that defines the Other, where the person, in general, is thought on this masculine model that applies in reality to no one: a strictly rational, self-interested, autonomous individual not determined by emotion.

This gets to the other main theme of Alien: that the true villain is the Company. Our heroes are working class folks on a cargo vessel. They just want to get home and get paid. But then they are re-routed by a suspicious distress call, which leads to their terrible discovery and predicament.

Was this a case of well-intentioned policies to help those in need going awry? I don’t think so. There is every indication that instead, the Company was in search of the alien; or, at very least, once it has been discovered, we are informed that preserving this being, supersedes all other priorities, including the lives of the crew.

This is a cold capitalistic logic combined with scientific hubris. It is quintessential to phallogocentrism.

Whether the xenomorph is feminine or beyond male and female is largely beside the point. The hermaphrodite/androgyne tends to be put on the side of the woman, after all. If things are defined from a masculine perspective, both are Other.

What greater horror, then, than for this alterity to exert its power in an overwhelming way? To be presented with a being that is not only beyond reason but beyond what we can biologically understand?

Cut it and it will burn you; its blood is acid that might even bring down the walls of your ship. Hit it with fire, or hit it with cold, and it keeps going. It is the indomitable force of the Unconscious, the Feminine, the Other—and thus I ask: should we perhaps not be on its side against the forces of patriarchy and capitalism?

Man—that long stand-in for humanity in general—is no one. The normal person (considered to be rationally self-interested and so on) does not exist. We are all Other, and the alien merely represents that in the extreme.

She is not the instigator. It was the man who decided to poke in her eggs who unleashed the violent backlash. And perhaps he himself wasn’t the worst guy, but isn’t there something satisfying about this image of a man being forced to birth something against his will? The appendage is forcibly stuck down his throat and the baby bursts from his stomach.

Of course, it is in this regard that I have always viewed Alien as an unabashedly pro-choice film. The idea that I would have to explain that to anyone bewilders me. Anti-choice laws aren’t about respect for life; they are about controlling women’s bodies. And if you want to come back at me with the difference between a human baby and the infant xenomorph, well, you’re missing the point.

Why wouldn’t the alien have a right to life, too? Because it is other? Because it is strange? Because its birth involved killing its host?

This is a being driven by its own biological imperative, and though that might be greatly at odds with the survival of the human beings on the ship, nothing warrants us to jump to the thought that it is “evil” other than its radical alterity.

There is no compromise, true. There is no reasoning with this being, and no common ground available. And yet, it was the humans who came into its nesting place and disrupted it. It was the humans (with android) who wanted to somehow harness it for purposes, and at the end of the day, it doesn’t seem to be doing what it does out of revenge, so much as doing what it does as the kind of being it is.

At a symbolic level, then, the fact that the ultimate showdown is with Ripley is significant. If we take the xenomorph as representative of the Other, with all of these associations with the feminine tied up in that, then we can think this final contest as one between two versions of feminine strength.

On the one hand, we have the xenomorph—an unbridled force of alterity—and on the other Ripley, who tries to work within the system, but largely goes unheard, with her orders being undermined more than once.

Of course we want Ripley to win here—the otherness of the alien is just too much—but at the end of the day we should recognize that she’ll be in trouble. The Company put all interests below that of delivering this species—which they wanted to put to their own ends. (And the time-jump at the beginning of Aliens is thus a real cop-out.)

And so, when Ripley kicks it out the airlock, she is jettisoning a force that could be far more effective at attacking the Company than her own. She has to, of course: this is too much.

Now we’re back to the jockeying and bargaining we have known for far too long. Of course, we prefer Ripley to the xenomorph—the strong woman to the unbridled forces of the Other—and I’m not saying we shouldn’t.

But it is all too easy for her to be sucked into the forces that seek to control her (as we see in Aliens), whereas the alien stands outside of that. It precisely represents that which cannot be assimilated or controlled. And in this regard, perhaps we should actually be on its side.

Smash the patriarchy.

the alien really doesn’t get a voice.