I purchased my Criterion copy of A Man Escaped (1956) during one of the recent sales. Following its arrival, I was checking it out on my DVD shelf and describing it to my wife:

“It’s like The Shawshank Redemption if you felt every single year of Andy Dufrey’s 19 year stay at the prison…but in a good way.”

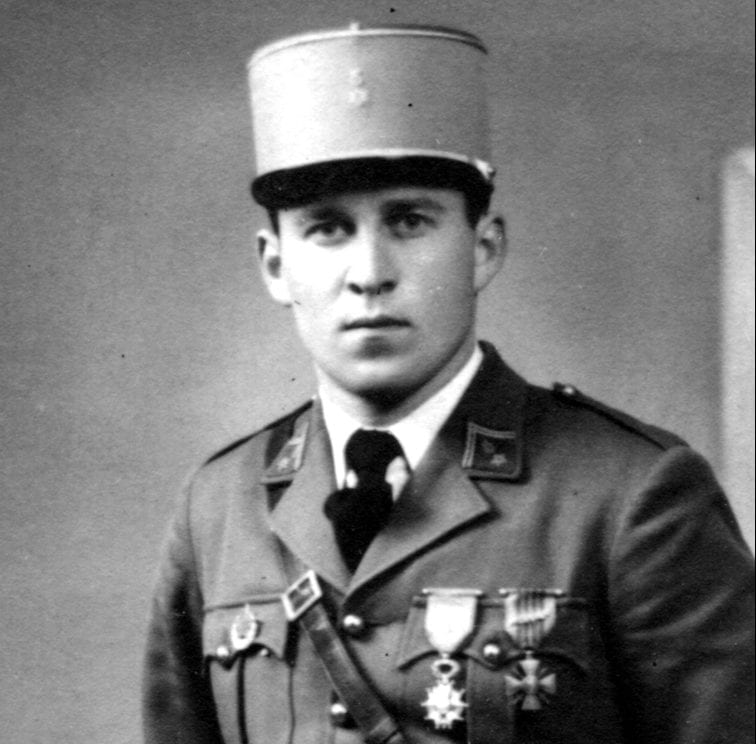

A Man Escaped is based on the memoir of French soldier and resistance fighter André Devigny’s 1943 escape from France’s Montluc prison during the Nazi occupation. The Nazis held, interrogated, and tortured enemy soldiers and resisters at the prison before having them killed or sent to concentration camps. They imprisoned approximately over 15,000 people at Montluc and executed over 900. The Nazis also held resistance fighter Robert Bresson (not in Montluc), and in 1956, Bresson (now a writer and director) chose Devigny’s memoir as the basis for A Man Escaped or: The Wind Bloweth Where It Listeth, to give it it’s full title.

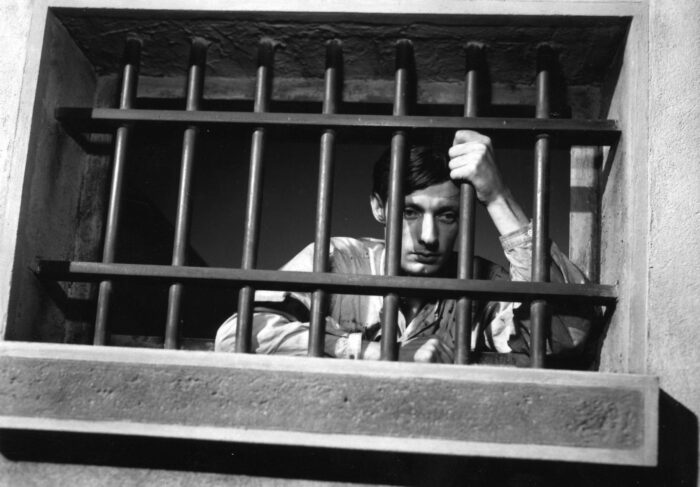

The film follows resistance fighter Fontaine (played by François Leterrier) as he attempts to…um…escape from France’s Montluc prison during the Nazi occupation. Yes, Bresson’s story, while obviously fictionalized, is a pretty straightforward and true recreation of Devigny’s actual prison break. Bresson was insistent on accuracy. He shot the film in the Montluc prison and even used some of Devigny’s actual escape tools in the movie. Bresson wanted to achieve a greater purity and simplicity than he ever had before. He cast non-professional actors for the first time, he uses almost no musical accompaniment, his story is simple and he gives us no big set pieces or huge scenes of action.

The lack of the usual movie flourishes brings a reality to the story that makes it all the more brutal and gripping. Not that we see very much. Violence against Fontaine and the other prisoners is all off-camera, and Bresson gives us little information to go on for the story and characters. We know almost nothing about Fontaine except why he was imprisoned, and his story before and after the prison is an unknown that we fill in ourselves for more interesting and satisfying results.

About the only thing Bresson does show and tell us about in detail is the titular escape. Oh, boy, do we learn about it. This movie has a very specific pacing that makes you feel every agonizing, tedious second of Fontaine’s plan.

Fontaine acts like a 1940s French MacGyver as he uses whatever’s around him to break free. He files down a spoon handle, making it sharp enough for him to methodically scrape away parts of his wooden cell door. This, in theory, will allow him to remove enough door planks to leave his room. He uses pillowcases, shirts, blankets and wire to create rope over the many months of his imprisonment. He even fabricates metal hooks out of an object in his room.

The tension as Fontaine slowly (painfully slowly) formulates and executes his plan is some of the best you’ll see in any movie. True to Bresson’s intentions, the director isn’t showy. His most effective tool is sound. Footsteps. Coughing. Glass breaking. Things dropped on the hard ground with a resonance that feels like it vibrates the whole prison complex. This film lives and dies by its sound design. It’s what will put you on edge. Fontaine’s anxiety over being caught after hearing guards shuffling around below his cell will well-up in the pit of your heart as you almost feel like you may be caught, too. It’s a masterwork achieved with almost nothing.

The lack of a score or almost anything works to the story’s benefit. It doesn’t distract you with different filmmaking elements and tools, such as swelling and intense music, clever editing or elaborate camera moves. It focuses you solely on Fontaine’s actions and the forces lurking outside his cell that could mean his ruin.

There’s also just something engrossing about seeing a smart, resourceful person acting sensibly as he enacts a long, sound plan. We’re so accustomed to seeing characters acting illogically just to create drama that seeing the opposite is refreshing. Bresson is a writer who knows it’s possible to obtain conflict, drama and suspense without forfeiting a character’s intelligence and common sense. I was so set on rewatching A Man Escaped partially because of its smart script.

I first saw A Man Escaped during a college film class. If memory serves, I found it interesting but a little boring. I also found the ending abrupt, anti-climatic and a little too easy.

Now? I still find the ending abrupt, anti-climatic and a little too easy. It’s not easy. It really isn’t. The whole film is about this prison break and the difficult lengths Fontaine goes through to make it to freedom.

But Bresson doesn’t linger enough on that last roadblock to liberation. He doesn’t milk it for all its worth. It’s maybe the one instance where I would’ve shot a little more intricately: close-ups on hands about to mess up or on Fontaine’s nervous face. That type of thing to just heighten tension one last time before the final release and resolution. Bresson could’ve accomplished this without sacrificing much of his simple aesthetic. I admire Bresson for sticking to his style from first frame to last frame, but that climatic moment needs something more. When we got to the end, I remember my college class being like, “That’s it?” I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel similar now.

The story does drag just a teeny, tiny bit, too. Fontaine sometimes over-explains in his internal monologue as he exposits about every step of his plan. Early on, Fontaine figures out how to get free of his handcuffs. After he the first time he does so, Fontaine narrates, “I felt a sudden sensation of victory,” while we can clearly see him smiling in victory. Bresson doesn’t always believe in the visuals and his actors’ physical acting to tell the story. He feels the need to spell things out, which is frustrating and not very trusting of his audience. It’s a minor frustration, but it bugs me. Bresson could’ve done better than that.

But at the heart of A Man Escaped is a tale of humanity. To further the comparison I made to The Shawshank Redemption earlier, it shares a similar theme of hope in the face of despair and insurmountable odds. But Shawshank (recently reviewed by 25YL) focused on characters and arcs while the prison break was not so much in the background but behind a curtain of mystery. A Man Escaped is the reverse. The breakout is in the forefront, the character stuff only sporadically seen.

The theme is there. While practically every other prisoner has resigned himself to death or at least a lifetime of imprisonment by those who seem destined to win the war, Fontaine refuses to give up. He must fight on. He will have a life beyond the prison walls. Fontaine is undeterred by the pessimism that pervades the prison. He even encourages the elderly man in the cell next door to not give up, to not give into hopelessness. They must all fight on till the end and look towards a happier life. It’s touching and inspiring but so underplayed that some might miss it. Shawshank certainly chooses to be more obvious with the idea, but A Man Escaped is no less powerful.

A Man Escaped is available on DVD and Blu-ray and is currently streaming on The Criterion Channel.

Thank you! Appreciate the kind words!

Well articulated summary and analysis of Bresson’s (and France’s) great films.