When I was eight or nine, escaping the humid and oppressive stickiness of Tampa weather on a lazy summer day by channel surfing, nothing made me flip the channel faster than seeing a Western film. In my young, illogical brain, a Western was simply a sickly yellow-hued monstrosity that “old” people watched; a dead genre that kids steered clear from. We wanted outer space and dinosaurs, not sweaty men in cowboy hats riding around in the sand.

Of course, little did I know at the time, but my favorite space adventure, Star Trek, was, itself, a Western, something Gene Roddenberry described as “Wagon Train to the Stars”. The concept of tackling new frontiers, meeting new groups of people, and solving problems by successfully merging cultural concepts is a way that many Westerns function.

The genre, when properly used, can show how alien America’s own homeland was to its residents, be it the physical formations of the Earth, with miles of empty dirt, temperamental weather, and formidable mountains, the exotic creatures, including snakes, vultures, and mountain lions, or the mixture of races, be it the indigenous Native Americans, the transplanted Chinese, or the former city folk looking to make a profit with (or against) the first generations of frontier families unfamiliar with East Coast society.

As I got older, the Western became a sought after genre for me to peruse. What helped was that the genre itself was no longer the most in-demand product as it was in the early days of cinema. When I was growing up, Westerns were released sparingly, and when they were, they looked to deconstruct the tropes and focus more on the human condition and the near-madness of conquering land that is barely conquerable; a literal man vs. nature debate made celluloid both from the perspective of trying to create society from nothing in a hostile world plus what happens when man is left to his own devices, without the comforts of centuries-old traditions and mass groups of people.

The idea of Western-as-thought-piece is what eventually drew me to it. Unforgiven, Clint Eastwood’s Best Picture-winning epic, was, at least until I saw The Wild Bunch years later, the perfect Western for me. It exemplified human consequences and perfectly encapsulated man vs. nature, both the physical nature around him and the psychological nature within him. While I do enjoy the occasional Western action adventure or comedy, I am more drawn to the raw, realistic look at frontier life that Unforgiven presented.

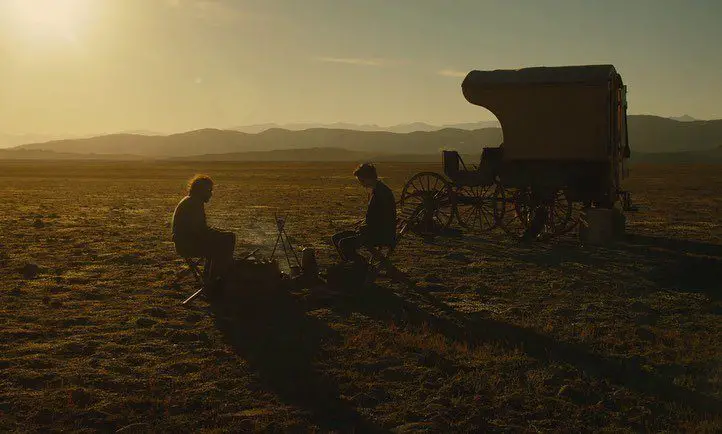

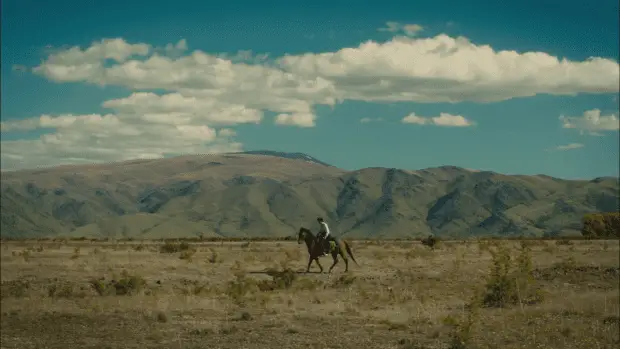

Which brings me to Slow West. This little-seen film contains all of the aspects of the Western that appeal to me, using its epic cinematography to really sell the scale of human intervention in an endless landscape of untamed earth. When characters are virtually swallowed by their surroundings, with barely anyone to speak to, the internal monologue is what drives the characters forward, backward, or crazy.

When we begin Slow West, sixteen-year-old Scot Jay Cavendish (Kodi Smit-McPhee) has traveled from his home on the English Isle all the way to Colorado in the United States in the hopes of finding his true love Rose Ross (Caren Pistorius). Forced to abandon Scotland due to the unintentional murder of one of Jay’s relatives, Rose and her father John (Rory McCann) fled to the far west in the hopes of starting anew, far from civilization, and away from anyone out to get them.

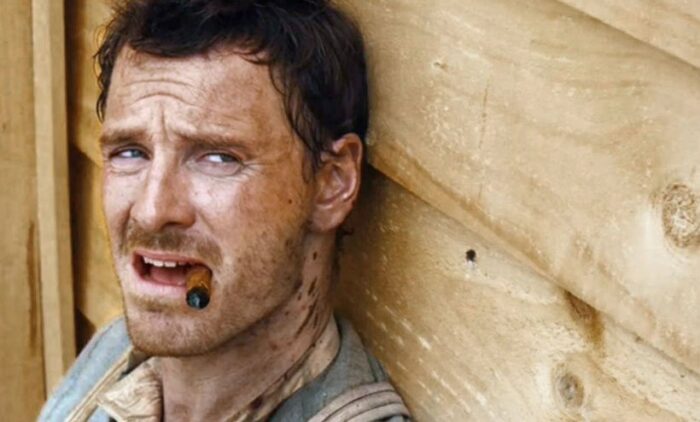

While Jay simply wants to find Rose and be with her, in any way he can (she doesn’t share his intense affections), a number of local bounty hunters are looking for her and her father as well, as the bounty for the murder in Scotland has come all the way to America itself. Trailing Jay, and thus being led directly to Rose, is mercenary drifter Silas Selleck (Michael Fassbender), who offers his services as guide and protector to Jay all with the intention of abandoning him when Rose and John are in his sights (a glorious $2,000 reward being given for their death or capture).

Though Silas sees Jay as a means to an end, and the young inexperienced teen is far too kind and naive to assume he would be double-crossed, the two begin to form a bond as the merciless Silas begins to see the true selfless love Jay has for Rose. He also needs Jay when Silas’ old mercenary crew, led by smooth-talking Payne (Ben Mendelsohn), starts to track Jay himself. As the road to Rose grows ever shorter, Silas must decide if he should truly protect Jay or go after the much-needed money.

Slow West is only 84 minutes long but it feels a lot longer, in a good way, by how big the scope is, both emotionally and physically. The way to amplify the personal journey of Jay Cavendish is by making the surroundings around him almost surreal. This is a teenager, a lovesick one at that, literally crossing oceans and foreign lands to find someone who he refuses to see doesn’t love him the way he does. It is basically puppy love taken to the extreme.

To Jay, his journey is traditionally romantic and it isn’t just a trip, but a quest. So as we go through the movie with Jay as our guide, we see the land as he likely would: larger than life and perhaps bigger than it should be. Helping to accomplish that viewpoint is Academy Award-nominated cinematographer Robbie Ryan (The Favourite), who plays with empty space throughout. Nary a minute goes by when we are not reminded that Jay is just this small creature in a vast world.

Assisting Ryan in his endeavor to give Jay’s journey a surreal and slightly fever dream quality is the New Zealand landscape in which the movie was filmed. Though the story takes place in Colorado, in the US, and Scotland, in Europe, the totality of the film was made in New Zealand. Residents of the US may see the similarities in the desert like landscape and may even be fooled in thinking that what they are seeing is America’s wild west but the mountain formations, uniquely chosen array of flowers, and the alien-like boulders and quarries of New Zealand lends this interpretation of America’s frontier a pseudo-fantasy vibe, as Jay himself no doubts sees it as in his adolescent mind.

While Smit-McPhee is a fine young talent and Pistorius does a competent job as a hardened and tough Rose, all the praise, at least in my mind, must first go to Michael Fassbender, one of the generations finest and most intense actors. I only found Slow West thanks to some friends who were using it for a film class they were teaching and, knowing my appreciation of all things Fassbender, pointed me towards it.

Selleck is not the richest character Fassbender has been asked to play so you won’t see the wide range of emotional depths he’s provided in such films as Shame and 12 Years A Slave. But it is his simple presence, as the tangible piece of reality that could and should humble Jay’s slightly quixotic journey to find Rose, that keeps the film centered. Jay is the dreamer, living in his dream, and Selleck is the one that has to pull him out of it to remind him of his limited life span, his dangerous surroundings, and those that will take advantage of him in the untamed lands.

“So, now…East. What news?”

“Violence and suffering. And West?”

“Dreams and toil.”

When we talk about Buried Treasures here on 25 Years Later, we often think of films that might never have gotten a fair shake but still have some sort of name value, be it of the infamous or cult variety. But Slow West might be one of the purest buried treasures we’ve written about as it is literally buried in the depths of Netflix’s streaming back catalog. The film grossed less than $230,000 in the US with a limited release and was sandwiched between two of Fassbender’s much larger X-Men projects. In 2015 alone, Slow West was trailing Fassbender’s own filmography, which included an adaptation of Macbeth and his Oscar-nominated turn in Steve Jobs.

But the fittingly termed slow burn of Slow West is what makes it such a great find, if and when you do indeed find it. It’s the philosophical approach to the human condition, as opposed to the tropes of gun duels and bar fights, that makes it a pleasant surprise and fitting for a comfortable evening at home or when Westerns should usually be enjoyed, on a warm Sunday afternoon when you’re bored and, unlike ten year old me growing up, less judgemental of what the Western genre offers.