The kind of long narrative of serialized TV can be wonderfully immersive, but here at 25YL we also recognize the value of a great standalone episode. Join us as we explore horror and sci-fi anthologies old and new, along with some other standout episodes of shows you love. This week, Rebecca Saunders examines an episode of The X-Files.

Few television shows have galvanized mass interest in science fiction as The X-Files has. The series began with a small, devoted viewership in 1993 but has expanded to attract global audiences 25 years later with its 11th season that aired in 2018. As we explore standalone episodes from horror and sci-fi anthologies, I will break down how The X-Files’ “Monster of the Week” episodes (separate from the show’s overarching mythology) often employed science fiction concepts that have since gained standing in scientific fact. In “Ice” (Season 1, Episode 8), Mulder (David Duchovny) and Scully (Gillian Anderson) struggle to quarantine a deadly mind control parasite that was discovered in arctic ice. In retrospect, “Ice” is somewhat comical in its simplistic depiction of deadly parasitic bodily invasions. Yet, its foreboding conceptualization of now proven scientific theories, such as parasites that can manipulate their hosts’ behavior and multicellular organisms that can survive millennia in arctic ice, rings ominous.

In “Ice,” Mulder and Scully investigate a mysterious mass murder and double-suicide that took place among a team of researchers working on the “Arctic Ice Core Project” in the remote wilderness of Alaska’s Icy Cape. They travel to the research facility with a geologist, Dr. Murphy (Steve Hytner), a physician, Dr. Hodge (Xander Berkeley), a toxicologist, Dr. DaSilva (Felicity Huffman), and their pilot, Bear (Jeff Kober). Upon arrival, Bear is bitten by a dog in the facility who had been exposed to the infectious toxins that caused the researchers’ deranged and violent behavior. Throughout the episode, the dog’s and Bear’s infection provide information about the parasite that spreads by driving its host to commit violence.

Eventually, the investigators discover that the team of researchers encountered this deadly parasite when drilling deep in an ice shelf that covers a meteoric crater. They confirm that the parasite comes from the ice by finding its microscopic larvae both in ice samples and in the deceased researchers’ diseased blood samples. Bear becomes increasingly agitated as Mulder, Scully, and the other investigators learn more about the parasite. When he tries to leave without submitting to a medical examination, they subdue and restrain him. They see a foreign object wriggling beneath the skin at the back of Bear’s neck, and he dies after Dr. Hodge extracts a huge worm from him through an incision.

Scully then extracts worms from each of the researchers’ autopsied bodies, learning that the parasite attaches first to its host’s spinal column and then to the hypothalamus in their brain. Since the hypothalamus produces the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, she concludes that the parasite is responsible for its host’s irrational, violent behavior. Only one of the worms from the researchers’ bodies survives extraction, so they keep the two worms—the one from Bear, and the other from a researcher—in a cooler. During the night, Mulder finds Dr. Murphy’s body in a different cooler with his throat slit. Immediately, it becomes clear that someone else among the team of investigators has been infected with the parasite. Because Mulder is found with Murphy’s body, the others suspect that he is infected and lock him away. The viewer, however, knows that Mulder did not kill Murphy and is not the parasite’s host.

Eventually, Scully discovers by examining the behavior of the microscopic larvae that larvae from different parasites will inevitably kill each other. They put the two surviving worms’ jars next to one another and, like a couple of beta fish, the worms combatively try to get at one another through the jars. By this rationale, the remaining members of the investigative team infer that putting a new worm into an infected host will cure them because the two parasites will annihilate each other. They test this theory out by slipping one of the worms into the infected dog’s ear. Next thing you know, the dog is behaving normally, and Dr. Hodge announces that the dog has passed the parasites in his stool.

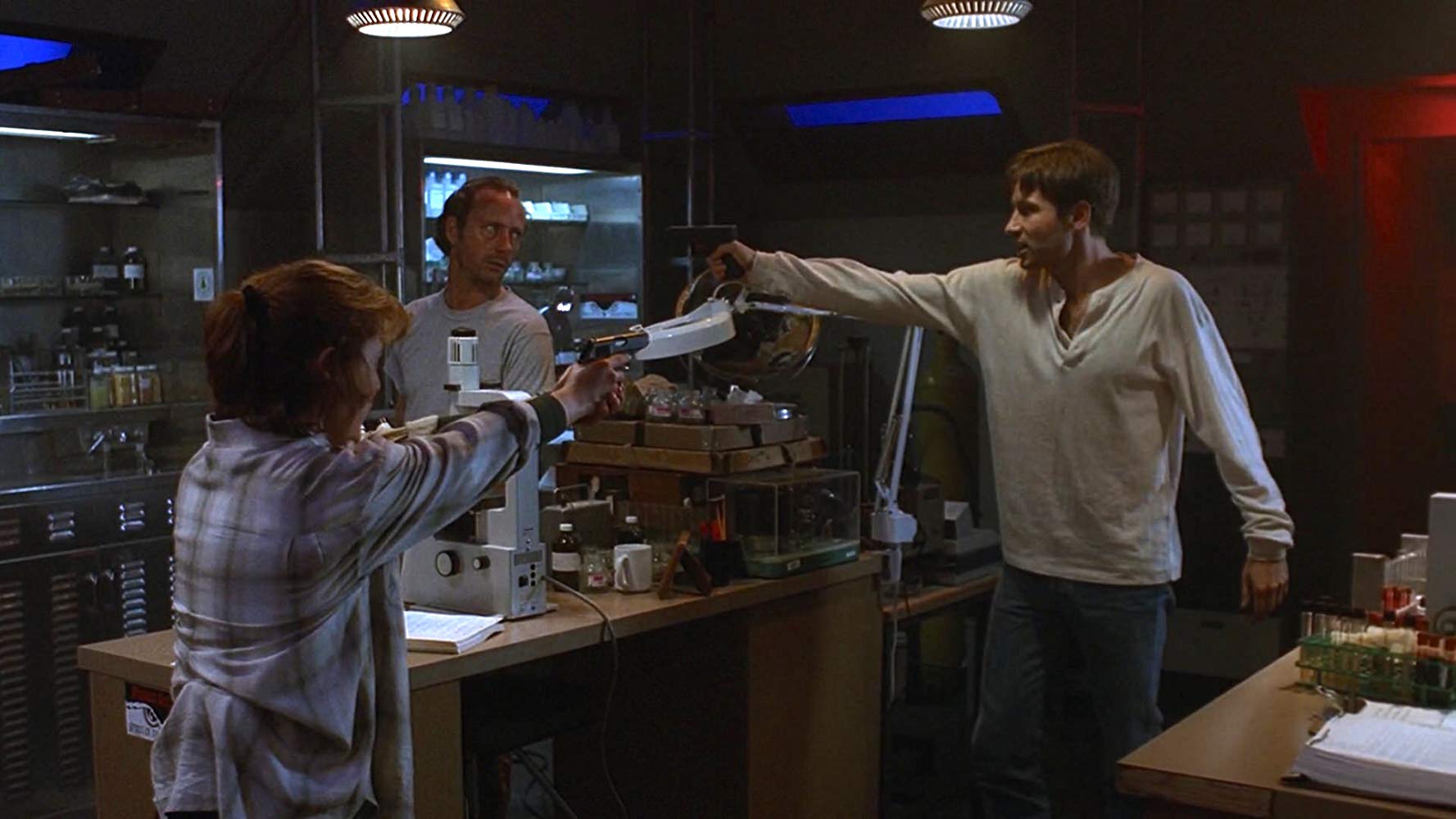

The team must now decide who is the parasite’s actual host. Making the wrong choice runs the risk of administering the worm into a new host, and they’re down to their last arctic ice worm, so there can be no do-overs. Scully examines Mulder and doesn’t believe that he is the host, but Dr. Hodge and Dr. DaSilva attempt to put the worm in his ear against Scully’s wishes. At the last moment, right when Dr. DaSilva is about to infect Mulder with the parasite, Dr. Hodge notices the grotesque wriggling of the worm beneath her skin. The group overpowers DaSilva and inserts the worm in her ear, effectively dispelling the risk of contaminating the population with the parasite once and for all.

Overall, “Ice” is an excellent standalone episode from The X-Files. It was influential in ways that earned the new show critical acclaim and set tones that affected the series for seasons to come. The tense undertones of paranoia and distrust required Scully and Mulder’s complex relationship to develop more fully in a way that was necessary for the success of their dynamic throughout the series. Also, critics have noted that Scully was depicted as a more competent and intelligent investigator than in earlier episodes from the first season, defining her character as coequal to Mulder’s. For the first time in the series, in “Ice,” Scully is not being led by Mulder through bizarre paranormal scenarios that are insurmountably foreign to her; here, Scully and Mulder are equally vulnerable and their mutual trust is tested. Scully’s expert scientific acumen is necessary for their escape from the arctic research center.

The conceptualization for “Ice” is largely indebted to John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982) and to the 1938 novella that The Thing is based on, John W. Campbell’s Who Goes There? “Ice” draws from The Thing’s notion of an extraterrestrial parasitic organism infecting a group of arctic researchers, who come to realize that they cannot trust each other as paranoia sets in. However, inspiration for “Ice” did not only come from science fiction precedents. The X-Files writer Glen Morgan was first inspired to write this episode after reading a Science News article about men in Greenland who found a 250,000-year-old item encased in ice. [1] Biologists have confirmed the scientific verisimilitude of “Ice,” explaining that parasitic worms really can attach to the human hypothalamus because it is not blocked by the blood-brain barrier. [2]

It’s still there, Scully. 200,000 years down under the ice.

True to its initial conceptualization as science fiction based in fact, more recent scientific discoveries about the survival of ancient organisms in arctic ice and about the mind-control capabilities of parasites have legitimized the terrifying potential for events similar to those depicted in “Ice” to actually occur. In the past few years and as recently as this very month, multicellular organisms such as nematodes have been thawed out and resuscitated after being frozen in arctic ice and permafrost for as long as 40,000 years. [3][4]The notion of primordial life forms potentially reawakening to our epoch as arctic ice melts in rising global temperatures is unsettling enough but hold on to your hats because recent research about parasites is even ghastlier.

Now proven scientific theories reveal that parasites really do have the ability to infiltrate the neural command centers of a host organism’s brain to manipulate its behavior in ways that are often fatal to the host. [5] Researchers are discovering that parasitic microbes and multicellular organisms are powerfully dominant in the biosphere, and new theories abound that parasites directly influence human behavior. [6] This isn’t all to say that ancient and/or extraterrestrial worms are liable to thaw out from arctic ice and start permeating human brains on a massive scale (…or are they?). However, “Ice” as a standalone episode from The X-Files is a testament to the show’s ability to thrill and chill us with gruesome tales that blur the definitive line between what is and is not possible. Join me in weeks to come as I take further close looks at standout X-Files episodes that remind us, as always, that truth can be stranger than fiction.

[1] Goldman, Jane. The X-Files Book of the Unexplained. New York: Harper Entertainment, 2008.

[2] Simon, Anne. The Real Science Behind the X-Files: Microbes, Meteorites, and Mutants. New York, Touchstone, 2001.

[3] Solly, Meilan. “Ancient Roundworms Allegedly Resurrected from Russian Permafrost.” Smithsonian Magazine, 30 July 2018.

[4] Ackerman, Daniel. “Ancient Life Awakens Amid Thawing Ice Caps and Permafrost.” The Washington Post, 7 July 2019.

[5] Jones, Lucy. “Ten Sinister Parasites That Control Their Hosts’ Minds.” British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), 16 March 2015.

[6] McAuliffe, Kathleen. This Is Your Brain on Parasites: How Tiny Creatures Manipulate Our Behavior and Shape Society. Boston: Mariner Books, 2017.