1994 was the year I started high school.

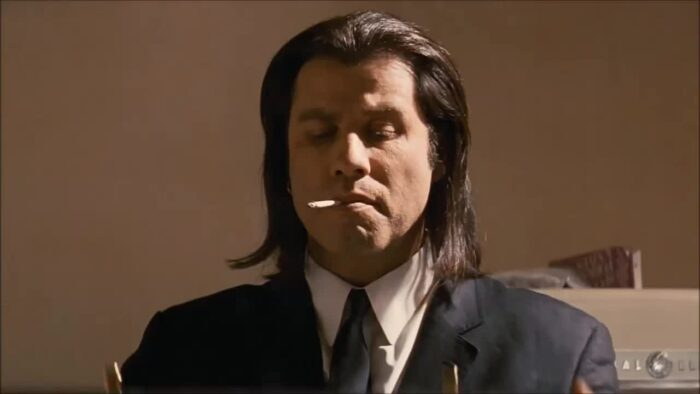

I was 14, or maybe 15, the first time I saw Pulp Fiction, which came out that year.

I’m struggling to remember when I saw it, is what I’m saying. I think I remember the circumstances—visiting my brother, who is six years older than me, and so on—but it doesn’t quite all work out when I try to pin down what the logistics were.

Regardless, this film was seminal—not just for me, but for the whole decade and the ethos of it.

Look at the big brain on Brett!

Pulp Fiction gave us a nonlinear narrative, and, sure, there were any number of films that did that before it did—it’s not like Tarantino invented something here—but I think it’s fair to say that a lot of us hadn’t encountered this prior to Pulp Fiction, particularly if we were young. But, it was also because successful films in the U.S. had not tended to be so experimental in their structure.

The film snobs came out of the woodwork right away, of course, if you were on the internet (such as it was) back in the mid-90s, but for the most part we didn’t give them much credence (or didn’t even have the internet). This was a cool fucking film, and it broke the mold of what we thought movies could do.

It wasn’t just the nonlinear narrative, either; it was how dialogue dependent the film is. There may be moments of action, but here is a film where almost every line sticks in your mind and becomes something you quote to your friends as a kind of shorthand, or in-joke.

When I watched it again in preparation for this piece, I found that I still have the film virtually memorized—not that I could recite it to you off the cuff, but I could tell you what the next line is at pretty much any given moment.

What made it have such an indelible impact? Why did I have a friend in high school who tried to style himself after Vincent Vega? Why did Pulp Fiction resurrect John Travolta’s career and save him from begging for Looking Who’s Talking Now Some More Also? to be greenlit? Why did it launch Samuel L. Jackson from the level of playing Mailman in Hail Caesar to the icon he is today (pretty much instantly)?

It’s not just that Pulp Fiction is a great film. It’s about the moment that it hit, and the way it defined the decade that was the 1990s.

The ‘80s had been a time of excess: cocaine, Glam Metal, Ronald Reagan, and the celebration of Gordon Gekko telling us that “greed is good.” It’s when the Boomers shifted from being the generation of the hippies to that of the yuppies, and if that doesn’t quite make sense, well, I guess I am just going to blame our less than rigorous generational categories.

Regardless, by the time 1994 came around, Reagan was gone, and so was George H.W. Bush. Those of us who’d been raised on “Just Say No” to drugs ads featuring eggs in frying pans and forced to endure D.A.R.E programs had started to come of age and realize the bullshit of it all.

If the youth of the ‘60s railed against The Man and protested the War in the name of trying to create a better world, the youth of the ‘90s were their children looking at their failure, and declaiming against them for “selling out.”

This wasn’t apathy, or nihilism, so much as a certain feeling of futility mixed with outrage. Bill Clinton was President. He tried pot, but “didn’t inhale.” The hypocrites were everywhere, and they were in power: a bunch of poseurs and sell-outs.

But there is really nothing to do but wear flannel and smoke cigarettes…

One Drink, and That’s It

So, then, there’s Pulp Fiction.

It’s slick, and cool—not in line with the grunge aesthetic of Nirvana, but not against it either. Certainly the film does not try to argue that we can, in fact, make the world a better place.

Its protagonists are criminals—all of them. They’re charming criminals, though: well-spoken, witty, and world-weary in just the right way.

Whether it’s Vincent’s generally lackadaisical demeanor (which makes the scene where he accidentally shoots Marvin in the face all the funnier), Jules claiming that he is “trying to be the shepherd,” Pumpkin (Tim Roth) trying to come up with a better plan as a robber, Butch shrugging at the fact that he killed the other boxing man as he made a move to change his life, or Marsellus saying that he is “pretty fucking far from OK,” all of the main characters in the film present a certain detachment from the idea that life is something to be cherished, and the rules something to be followed.

Instead, what’s interesting are questions that seem almost banal, but are taken with a level of seriousness in Pulp Fiction: are you a Beatles man, or an Elvis man?; is giving a woman a foot massage an act of intimacy?; what do they call a quarter-pounder with cheese in Paris?

We saw something similar with Clerks the same year, as Randal and Dante debated the morality of blowing up the Death Star in Return of the Jedi, for example. It was a move to think about things we’d passed over unthinkingly, and to use pop culture references as a way of doing so. And if anything ties Pulp Fiction and Clerks together, it is how the dialogue is really the most important thing.

And, thus, a whole world of independent cinema opened up. We didn’t necessarily realize it at the time, but this was a heyday. The alternative had become mainstream, not just in music, but in film, or at least close enough to it that any number of projects that would not have been funded before were, in the hope that they might be the next Pulp Fiction.

Geeks like me spent hours on IMDb (which at that point was really just a place where you could find out what else people had been in, and maybe about upcoming projects—no pictures, just cast lists and the like) seeking out other things that actors like Steve Buscemi had been in, and then going to see if the video store had them.

We weren’t interested in the glitzy Hollywood star; we wanted the Parker Posey. And I think Pulp Fiction has something to do with opening up this door.

We wanted something different, and perhaps we still do, but the sentiment in the ‘90s wasn’t based on some ideal about what that might look like so much as on a discontent about how things are. And so even the most objectionable bit of Pulp Fiction—when Tarantino himself appears and throws around some racist slurs—seemed oddly refreshing.

Because let’s be clear, kids, that was not at all OK in 1994. Things haven’t changed that much. Sometimes when I talk to younger people, it seems like they think there has been some radical sea change about things with their generation, when the truth is that they are just young.

I mean no offense by that, but it’s important. Heathers was offensive and disturbing when it came out, and so was the use of the N-word in Pulp Fiction. And Tarantino knew it was.

This might not be worth mentioning, except for the way in which a certain push against “political correctness” seems to have taken up some space on the side of the counter-culture. It seems as though any number of young people get sucked into the alt-right and the like in this way. They’re bucking against the system. And that was already there in 1994, and Pulp Fiction; the nugget of what seems to be an almost ironic racism.

Which, to be clear, doesn’t make it any less objectionable. The question is whether we understand, or seek to understand, or shut things down with our hands over our ears and vitriol in our mouths.

And, I’m sorry, but I still think Jimmie is funny. He takes the casual racism of many white Americans and lays it bare. He’s nonchalant about it.

Well you gotta have an opinion!

For the past 25 years, it seems, people have wondered what was in the briefcase. The most common theory—or at least one I have seen a lot—is that it is Marsellus Wallace’s soul. And I guess some credence might be given to this by the glowing light that emanates from the briefcase, Vincent’s reaction to looking inside, and so on.

But, to me, the whole question has always seemed to miss the point.

It’s that we don’t know what’s in there that is important.

Tarantino has given us a mystery object, and refused to elucidate what’s inside.

This is the key thing, that relates to the impact of Pulp Fiction as a whole: we’re not getting answers. It’s not even clear what this film “is about” if you think about it. But it doesn’t matter.

The absence of an answer adds to its power.

Because that’s the whole ethos of ‘90s all over again: we don’t know what the answer is, just that something is fucked. Something’s gone wrong, and it’s inexplicable; like Vincent shooting Marvin in the face.

You’ve gotta have an opinion, but what should it be? Maybe you just don’t even want to get involved in this.

And that continues, but I think it has gotten sort of weirdly worse.

Whereas in the ‘90s there was this kind of general dissatisfaction with the world, along with sense of despair about making it better, it increasingly seems to me that the young people of today aren’t even dissatisfied so much as they are resigned—this is the way the world is, and there is nothing to change it.

There is no justice. There is no peace. But, you know, that’s just how it is.

Pulp Fiction is not really a political film, but I think it captured the zeitgeist of its time, and contributed to how that developed.

And, for those of us who got caught up in that, perhaps Jules quandary continues to ring true:

I’m trying, RIngo, I’m trying real hard, to be the Shepherd.