There’s a legendary story about folk singer Joni Mitchell and Woodstock. She wanted to perform but her producer, David Geffen, talked her out of it. He wanted her to appear on The Dick Cavett Show the day after the festival ended instead. He figured it was more important for her to reach a national TV audience. A little music festival at some guy’s dairy farm in upstate New York was low on the list of priorities.

As she sat in her hotel room watching news footage of teenaged hippies descending on Bethel, and as her then-boyfriend Graham Nash regaled her with stories about the festival he’d just performed at (with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young), Joni was hit with inspiration. She penned the beautiful and lyrically haunting song “Woodstock” despite never actually being there.

It went on to become a defining song of the generation.

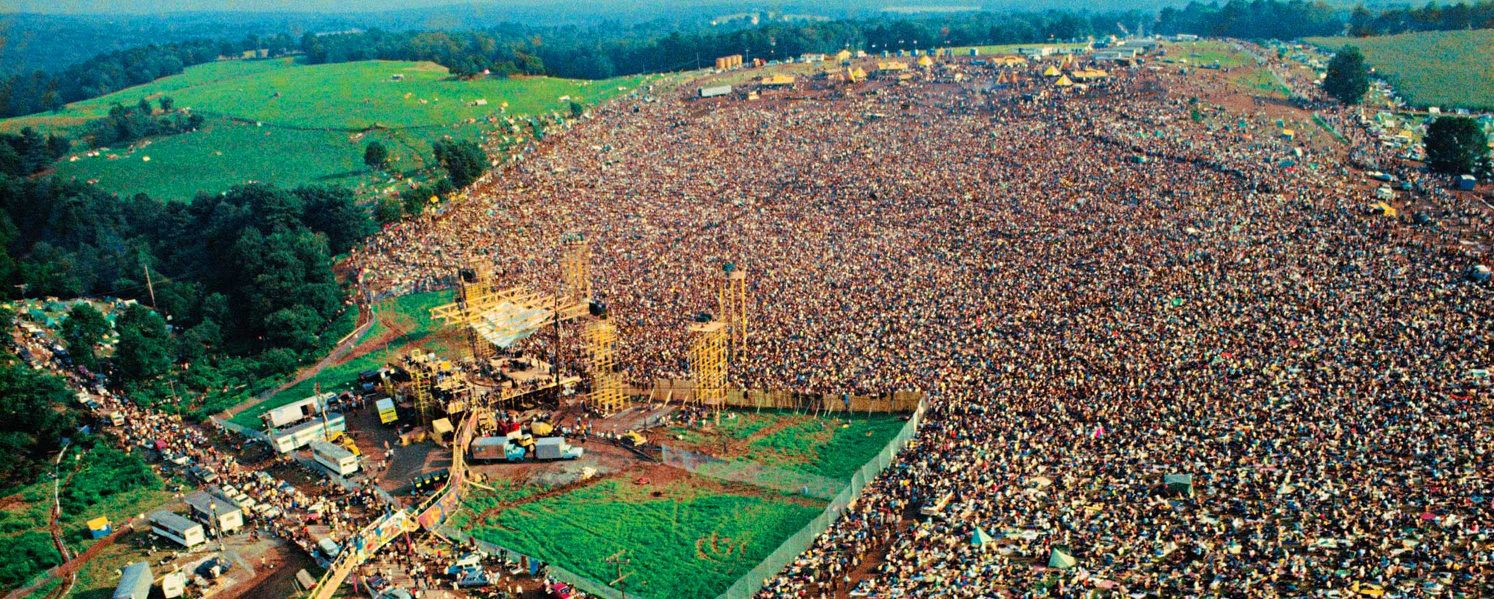

The organizers billed Woodstock as an arts and music festival, an “Aquarian Exposition”. It started off as a ticketed event with a planned attendance of 50,000 people. Half a million actually showed up. There weren’t enough washrooms. There wasn’t enough food. It rained, like, a lot. But over those three days in August of 1969, there were no riots, there was no looting. Just a lot of peace and love and music.

Joni Mitchell wasn’t there to see it. Still, her recording of the song might be the truest account of Woodstock. Her lyrics describe meeting a “child of God” walking along the highways up to the concert venue. This traveller intends to “camp out on the land” to “try and get [his] soul free.” She asks if she can go with him; she is going to find herself too. By the time they get to Woodstock, they are “half a million strong”, surrounded by song and celebration. The bomber jets—a reference to Vietnam?—turn into butterflies, no longer carrying weapons of war.

And there is that refrain, repeated at the end of every verse:

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden

It’s powerful stuff. Her haunting melody is lost in the grungy rumble of the CSNY version. Later, it was given a 70s AM radio colour by Matthew’s Southern Comfort. Joni’s original version sounds sad, wistful, nostalgic for something that was still happening, at least in the moment Mitchell was writing it. Maybe it’s sadness at missing out; but here, fifty years on, it’s difficult not to hear a kind of resignation in there too.

No one could have known that the time of unrestrained peace and love and harmony was nearing its end. In Los Angeles, the Tate-LaBianca murders had already been committed. By the end of the year and December’s Altamont festival—a kind of hopeful “Woodstock West” absolutely destroyed by violence, riots, property damage, and the deaths of four people—the promise of the 1960s were over.

I’m Going On Down to Yasgur’s Farm

The festival began as the brainchild of four men: Michael Lang, Artie Kornfeld, Joel Rosenman, and John Roberts. They originally wanted to build a recording studio, but these plans morphed into a massive one-time concert event instead. Musical and recording artists like Bob Dylan and The Band already called the upstate area home. It made sense to tap into what was then a grassroots industry. The four men scouted locations, and local resistance met them at every turn. Eventually, they made contact with a dairy farmer near Bethel, NY named Max Yasgur, who leased his 600-acre farm to the festival organizers.

The site chosen was perfect for a concert venue. Yasgur’s farm incorporated a large pond at the bottom of a large hill which formed a natural amphitheatre. The organizers’ expected 50,000-person crowd would be able to fit in the space easily. Various locations around New York City sold tickets exclusively, and once the location had been confirmed, it seemed as though the thing would go off without a hitch.

However, in the week before the festival was to begin, work permits were withheld by the Bethel Town Board and construction on the fences and stage area came to a shuddering halt. On Wednesday, August 13, people began arriving by the tens of thousands. Traffic jams were already starting to form on the highways leading into the area. Forced to contend with either an improperly fenced in area (which could lead to people sneaking in without paying) or an improperly built stage (which could lead to poor performances or worse, dangerous stage collapse) the organizers decided to build the stage and leave the fences half-built. This effectively turned the festival into a free event, something which nearly bankrupted the organizers as nearly 500,000 people descended on the site.

I’m Goin’ to Try and Get My Soul Free

Woodstock was a logistical nightmare from start to finish. It rained so much leading up to the festival that the field overlooking Filippini Pond effectively turned to mud. There was not enough adequate sanitation for the number of people in attendance. Food and water were in short supply. The mud made first aid difficult to deliver. Radio and television all over the state, and eventually around the country, spent breathless hours covering the lead up to the event, those interstate parking lots created by the stranded vehicles attempting to make their way to Yasgur’s farm. Helicopters from a nearby air force base ferried performers into and out of the festival site. Nelson Rockefeller, then-Governor of New York, at one point threatened to call in the National Guard. Roberts dissuaded him.

But we remember Woodstock as a cultural touchstone, a sort of magical confluence of time and space where the dreams of a generation came to full blossom to the soundtrack of that moment. To call the performance schedule, “organized” is a bit of a stretch; some performers missed their slots because of traffic or refused to play during the thunderstorms that shocked overhead. Some performers, such as John Sebastian, joined up onstage from their seats in the audience, conscripted to fill in at a moment’s notice when other acts failed to materialize.

(As a brief aside, when I watch the documentary or listen to the album, I don’t notice this chaos; perhaps that’s of the strength of the secondhand nostalgia for the event and the way it looms in the collective imagination, as interpreted by me. But the festival seems to unfold exactly as it should have if that makes any sense.)

The list of performers and appearances is a Who’s Who of countercultural icons and popular artists. The Grateful Dead, Janis Joplin, Santana, Ravi Shankar, Joan Baez, Creedence Clearwater Revival, The Who, Arlo Guthrie, The Band, Crosby, Stills, Nash, & Young—they’re all there.

It may be more surprising to see the number of people who you’d expect to be there but didn’t perform. Bob Dylan, a resident of nearby Woodstock, was never in serious talks to perform. Frank Zappa turned down the opportunity to play. So did Led Zeppelin. The Doors figured they’d already played the Monterey Pop Festival and this would be a second-rate festival to that one, and refused. The Beatles were trying to negotiate their attendance, which would have marked the first time in three years since they had performed live, but they rescinded their offer and never made the bill; neither did their recent Apple record label signee, James Taylor.

And, of course, Joni Mitchell never made it on that helicopter either.

But the performances we did get have become the stuff of legend — the opening invocation by Swami Satchidananda representing everything about the spiritual leanings of the people in attendance. The Who’s performance being interrupted by political and social activist Abbie Hoffman, who was protesting the jailing of White Panther Party leader John Sinclair, was a powerful reminder of the unrest that existed outside of the idyllic image of a peace-and-love-fest that everyone was trying to cultivate. Rainstorms and thundershowers effectively halting the final day’s performances, pushing the afternoon schedule back until evening and running through the night is something that gives new meaning to the phrase “all-nighter”.

This meant that Jimi Hendrix’s blistering headlining performance occurred around breakfast time on Monday morning.

The festival famously ended with two births and only two deaths. It produced a riveting 1970 documentary and a triple album that more than made up for the festival organizers’ losses as a result of making the event free to attendees. And it remains to this day one of the most important events of the 20th century.

We’ve Got to Get Ourselves Back to the Garden

The end of Woodstock brought with it the end of summer and the end of the Sixties in many ways. The sobering reality of the Manson Family’s reign of terror began to settle over America. Tensions between the government and its citizens over the war in Vietnam ratcheted with the reintroduction of a draft lottery. The horror of the My Lai Massacre received wide coverage on televisions the world over. And, finally, the December 6 Altamont Free Concert in California showed the dark side of these types of happenings. It all contributed to the growing cynicism and disillusionment that had been brewing since the Summer of Love. Gone, suddenly, were the dreams of a better tomorrow.

Woodstock now symbolizes something bigger than just a music festival. This is the best way to describe the fact that anniversary festivals—Woodstock ’94 and Woodstock ’99 instantly come to mind—continue to happen. Coachella, Glastonbury, Donauinselfest, Osheaga…how many of these would exist were it not for Lang, Kornfeld, Rosenman, and Roberts? Fifty years later, the idea of a festival weekend away still captivates us, even if the 50th anniversary of Woodstock itself is now officially a bust.

Woodstock may have ushered in the era of music festivals and cemented the 1960s in the popular imagination. But it was also the last gasp of the hippie and free love movement and the Sixties counterculture. These things devolved into lesser products as industry and commerce and greed watered it all down. They became the cults and communes of the 1970s, and later, somehow, the multi-level marketing schemes of the 1980s and 1990s. The people who came of age with Woodstock as their defining moment seemed, in a lot of ways, to never come close to that height ever again.

There’s a lot to say about the lost promise of the Baby Boomers. Perhaps it’s fitting that the last words here should belong to the woman who defined her generation so well. In a 2013 interview with CBC’s q radio program, Joni Mitchell had this to say about Woodstock, Boomers, and the Sixties:

“…Woodstock was the culmination of it. […] [M]y generation for most of the ’70s fell into apathy, sucked their thumb, heavy drugs followed light drugs, you know, the thing got darker and darker, and they didn’t know where to take it. And when the ’80s came along and the Reagans got into power, it went hippie, yippie, yuppie, and there was all of the shootings and the beatings and the Democratic convention with hippies coming this way and cops coming the other and their heads getting bashed in.

You know, seeing that America was an ugly and violent place at the governmental and the social structure of it. […] So they just didn’t have another plan so then they moved into—they were converted into consumers. Portfolio, play the Wall Street thing, consume, consume, they went right into the thing that their parents had on a bigger scale, on a greedier scale, make more money, make more money. Dallas, like, you know, crooked rich people are good. You know, the Reagans are good, Madonna “I’m a Material Girl,” you know, is good. All of the role models were to the shallow and the acquisitive. And we were converted from some kind of naive idealist…”

Naive idealism. “We’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden.”

Many would agree that the world has gone a bit pear-shaped since 1969, politically and socially and economically. Many would (and have) argued that the fault for this lies with the Boomers. But perhaps it’s not too late to turn the clock back and regain some of their idealism, tempered with a bit more wisdom this time, as we enter the third decade of the 21st century.