Horror runs, primarily, on the combustible chemicals of empathy and expectation. As watchers, as voyeurs on the dark rituals of screams and silver screens, we enter into an agreement. We will approach this film, like a hall of mirrors, and see our reflections in the dead, the dying, and the dealers of death. When John Doe compiles his journals and stages his Se7en murder setpieces, we wear his fingerprint-less hands like gloves, becoming the killer. When Sally wakes up to find the cannibal family of Texas Chainsaw Massacre staring at her, we feel her fear as though we’re tied to the same chair. We expect to empathize with the good or the bad from scene to scene. We’re hunters. We’re hunted. It’s an empathetic contract we sign in blood.

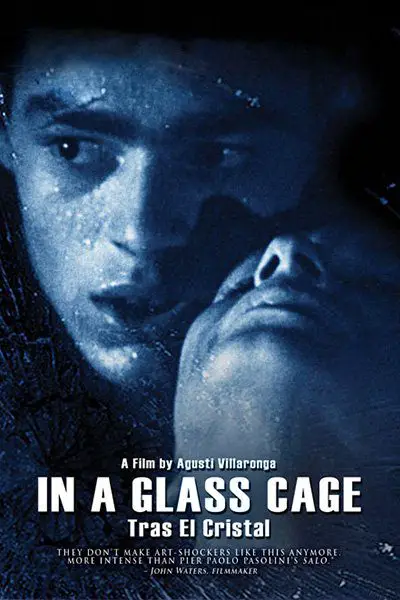

So, when the 1986 Spanish-language film, In A Glass Cage, and its writer-director Augustí Villaronga decide to tear up that contract in front of us, we are forced to feel something rarely felt in horror cinema: actual, unrelenting horror.

The story follows Klaus, a former Nazi confined to an iron lung and living in Spain with his wife and child. His wife is at her wit’s end and insists they hire a nurse to help see to Klaus’ unique needs. A boy, Angelo, soon darkens their doorstep claiming to be, conveniently enough, a nurse. Despite the wife’s misgivings about Angelo, Klaus insists he is hired to care for him. Angelo then reveals what he knows about Klaus’ dark secret identity. Klausn’t just a Nazi, he was also a pedophile.

On its face, the prospect of watching an aging Nazi be tortured and abused with memories of his crimes sounds relatively unchallenging, morally. We practically drool in anticipation of our vicarious time with Angelo, a righteous archangel, meting out inescapable justice to the one that got away. Angelo’s revenge, however, is not the white cowboy hat we signed up for.

Klaus confinement to the iron lung establishes a kinship with the audience. He sees his own life through an angled mirror, his head rendered immobile by the titular glass cage. His mirror, his screen unto the horrors of the film echoes the screens that show us the film. We are forced, by Villaronga’s impeccable direction and composition, to crawl into the cage with Klaus and watch Angelo’s actions with horror. We shudder at the skin we’re in, the vile persona of the Nazi doctor made helpless by circumstance. We, too, are helpless and ashamed at our empathy.

The characters in Villaronga’s script demand powerhouse performances that generate the empathy that the script needs. Klaus, played by Günter Meisner, needs to be as believably disgusting as a child-killing Nazi officer while simultaneously being pathetic enough to make Angelo look the monster he obviously is. He needs to feel, in every frame, like a man running from his unspeakable past towards a reformed life as a father, a husband, and a victim of circumstance. Meisner marches to this beat beautifully, communicating his character’s shame and fear with little more than a glance.

Angelo, played by David Sust, delivers one of the most unsettling, grounded, haunting performances in cinema, drifting from room to room and scene to scene with the gaunt, unflappable eroticism and sense of purpose of a Greek fury. His vacant eyes and soft voice evoke the listlessness of a masked Michael Myers with none of his humanity lost in the process. When the film calls for violence and sadism, Sust acts with the fluid grace of something more than human, charging even the most despicable moments of the film with an abject eroticism. It’s repulsive, but through the prism of Sust’s performance, we understand his attraction to it. He’s a singularly being, driven by a single purpose, and stroking himself closer and closer with each gesture and line.

Most astoundingly, however, is Gisèle Echevarría as Klaus’ young daughter, Rena. Her transformation from smiling innocent to haunted witness and, ultimately, something beyond description grabs any assumptions about child actors by the hair and drags a skilled blade across their throats. Despite the unrelenting maturity of a film about Nazis, guilt, justice, and the cost of vengeance, Echevarría never feels too young for the Herculean lift of her character.

In concert with these performances, Villaronga, with cinematographer Jaume Peracaula and production designer Francesc Candin, create a bleak and unforgiving world of Klaus’ home. Scene by scene, Angelo works not only to confront Klaus with the sins of his past but force him to live in the hell he created for others. He wraps the opulent columns of the villa with barbed wire and builds a bonfire of the furniture in the hall. Meanwhile, the color palette that teased with gorgeous reds and creams gradually shift down into post-apocalyptic greys, blues, browns, and blacks. We see how vengeance, in and of itself, even for the most righteous of reasons, takes all involved into Hell.

In that Hell, however, thanks to Villaronga and Peracaula’s vision, are the innumerable delights of devils. The filmmakers’ treatment of texture, particular of skin and the smooth glass of Klaus’ iron lung, create a visceral, compellingly sensual viewing experience. In A Glass Cage is a film felt as much as seen.

Herb Freed, the director of the slasher film Graduation Day, says of his experience making horror films, “it was good, but it’s good that it was.” When I watch something as unrelentingly bleak, disturbing, and uncompromising as In A Glass Cage, I understand what he means. Watching Villaronga’s film is a life-changing experience on par with Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salo or Pascal Laugier’s Martyrs. One viewing is enough for a lifetime.

A film as transgressive and nihilistic as In A Glass Cage fills its audience with the unnatural desire to stop the action. We want to hold Angelo back from his mission, we want to whisk Rena away from this terrible place, we want Klaus to suffer, sure, but not like this. We feel helpless, unhungry for more of the film, but starved of any way to intervene, and too enthralled by its meticulous composition to look away. It’s a time-lapse of a beautiful, decomposing corpse. It’s a Renaissance painting, rotting off the wall. Looking at our screens we understand Klaus and his glass cage all the better.