This month in PopCulture25YL, we’re taking a look at the music, shows, video games, and whatever else we want from the month that was August of 1994.

Mashing Buttons

EarthBound by Sean Mekinda

EarthBound (or Mother 2, as its known in Japan) may just be the world’s most perfect JRPG. I know, every fan of EarthBound will not shut up about it for that exact reason, but let me explain why they are right and why everyone should play EarthBound, even people who aren’t fans of JRPGs.

Turn on the game and you’re greeted with sci-fi buzzing, slowly building and building to a crescendo of silence. Then the screams start. The music is dire. Undistinguishable noises ring out, attacks from the within the music. Finally, the menu music begins.

Poppy jazz.

The musical whiplash sets the stage for everything you can expect. Existential terror, joy, quirky enemies, and adventure.

After naming yourself, your playable character (two separate entities), your dog, your friends, your favorite food and your favorite hobby, the game begins in earnest and you’re thrust into the totally-not-America Eagleland.

I honestly don’t want to keep talking about the plot, nor dive into the enemies or locations. It’s much better experienced with as little warning as possible. It’s weird, it’s haunting, it’s charming, and it will make you feel things. So instead, I want to talk mechanics.

Oh my god, the mechanics. There are no random encounters; all enemies are on screen. Once you get a high enough level, those same enemies start to run away from you. Level up even more, and the game doesn’t even make you fight them. Just a satisfying /thwack/ and boom, you get 7XP and a cookie. I have no idea how every RPG has not picked this up, because it makes traversal so much easier and so much more satisfying. Seeing the enemies that once gave you trouble flee before you is so, so sweet.

Beyond the overworld mechanics, the fighting is incredibly unique, even by JRPG standards. You don’t see your party, just the foe you are facing, staring directly at you. Combine that with the acid trip of a background and pulsing colors that are your attacks, and you feel like you could actually be face to face with a sentient pile of vomit (yes, actually). Well, one that lives in a world of SNES-quality graphics.

I could probably go on for quite a bit longer about the wonder that is EarthBound, but I have a word limit here and if I haven’t sold you on it by now, I don’t know what will. So excuse me while I go beg Nintendo to localize Mother 3 and finish up my yearly replay of EarthBound.

Need For Speed by Gus Wood

Burning rubber, screeching tires, revving engines, and nothing but green lights ahead of you and flashing reds and blues behind you. Racing games have always given us the vicarious thrill of high stakes automotive action, but something was missing.

Then, in 1994, Need for Speed came out for the 3DO and changed everything by adding that missing something: crime. Racing around a track in a race car with legions of fans can get the blood pumping, but, as Judas Priest told us, there’s nothing like breaking the law. Making a chase part of a race was a stroke of genius that turned Need for Speed into the start of the biggest racing game franchise of all time.

But there was a long road of rubber to burn before the world of racing games changed forever. Distinctive Software, a small games studio in Vancouver, British Columbia, enjoyed some nominal success in the racing space with forgettable titles like Stunts in 1990 and Test Drive II: The Duel in 1987 as well as some outstanding games like Outrun for the Sega Genesis.

When Electric Arts saw the opportunity, they bought and rebranded Distinctive Software into EA Canada and leaned all of the company’s driving game expertise towards a new kind of racing game, and the rest is history.

That history continued to be interesting, though. In order to help their game stand out, EA Canada consulted with actual card-carrying gearheads working for Road & Track magazine to ensure the cars of Need for Speed controlled and moved as close to reality as possible. Though this feature was abandoned as the series ballooned into racing game dominance, it’s still praised today for its ingenuity and verisimilitude.

Racing other cars under these conditions welcomed the player into an intense new world of driving. The game became beating the other guy with more than the pedal to the metal. There was precision steering and other quirks of mechanical behavior to consider. Moreover, the sounds of every playable car were verified by the Road & Track writers to further immerse the player into an authentic world of high-octane driving.

Need for Speed was a bold innovator on the 3DO that would start a frenzy of “street racing” games in the years to come. Finally, there could be a new kind of car game separate from the squeaky clean Pole Positions and Mario Karts of the gaming landscape. If those games wanted to share the road, they’d have to make room in first place for a racer with attitude.

No other game could satisfy the need gamers had for thrills. For excitement.

Nobody met that need like Need for Speed.

At the Comic Shop

If Charles Dickens wrote superhero books, it’d be Starman by John Bernardy

Starman is so goddamn good.

Somehow, in the middle of the grim and gritty attitude era of the ‘90s, a classy literate book by the name of Starman began an 81-issue run that completed the story auteur writer James Robinson had planned for Jack Knight and Opal City. We haven’t seen an author’s vision this complete except for Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, and the quality is just as comparable.

DC’s in-house ad for Starman included a quote from Oscar Wilde, which actually figures into the backstory of the Shade, a reformed villain and biggest honk for Opal City you’ll ever meet. The Shade was friends with Oscar Wilde, and over time we get to witness their chats. Starman respects the past of literature just as much as it respects the past of the DC Comics Robinson adored as a boy.

One of Robinson’s favorite characters was the science hero who created the flight-granting gravity rod—Ted Knight, Starman. He was a Justice Society member who debuted in 1941. The books were campy as hell, but Robinson loved them. When DC’s Zero Hour needed books to launch from it, Robinson pitched a story that included scientist Ted Knight—now former Starman—and his sons.

The son who idolized him, David, wanted so badly to be Starman but dies in his first mission in the early pages of Starman #0, which incredulously turns 25 years old this month. Ted’s other son, Jack, is our book’s unlikely hero. Jack’s not into his dad’s past at all. He’s into the past—deeply so—but only the other stuff. He’s an antiques dealer who knows the ins and out of Bakelite and View Master reels, all the movies back when they were called “the pictures.”

But Jack wasn’t into his father’s superheroics. He stayed the hell away from it and only gets involved because the in-case-of-emergencies cosmic rod he begrudgingly kept saved his life when supervillains blew up his antique shop. David didn’t have “the stuff,” but Jack does. And he learns about being a hero through over 80 issues of this extremely stylized comic book epic.

And speaking of stylized, artist Tony Harris does art deco like no one’s business. Check this out:If you couldn’t tell from that purple prose, Starman really is very much “if Charles Dickens wrote superheroes.” It’s serialized. The city is a main character. And said city is filled with hundreds of wonderful characters and a history that is delved into regularly. Along the way we meet these characters, including the mysterious fortune teller Charity, the plentiful O’Dares (all of them cops), Bobo Bonetti (who Robinson wrote so convincingly his own editors believed Bonetti was a genuine Golden Age character), and even existing characters like the fun husband-and-wife detectives Ralph and Sue Dibny (Ralph being the Elongated Man). The Shade was originally a goofy villain that popped up in The Flash, but Robinson classed him up to the nines. Robinson also turned oft-villain Solomon Grundy into a peaceful endearing giant who couldn’t hurt a fly, until he could again (which was heartbreaking).

Every time the main artist needed a break, Robinson used his time with guest artists to tell stories of Times Past. One of Ted’s old capers, or another Starman’s. Maybe just a night in Opal City that goes wrong and then right. Those Times Past stories add color, but it also keeps the main story feeling like it’s in a special space all its own.

Over the course of Starman’s run, you learn all kinds of Opal-textured character ticks from all kinds of people, including Batman’s favorite Woody Allen movie. While it solidifies the presence of Opal City, this book is all about capital-L Legacy, both for the Knights, and also the identity of Starman itself.

During the series, we meet every character who’d ever worn the title Starman, including the ‘80s version Will Payton, and a blue-skinned alien by the name of Mikaal Thomas who appeared in 1st Issue Special #12. And once a year, we get a Talking With David issue, where Jack meets his dead former Starman brother in a dream.

The main theme of the book is the interplay between the older generations and the current one. And, at the end of the day, it’s a book about fathers and sons. It’s about Jack growing into adulthood and learning how to have a respectful relationship with Ted as Jack grows into his legacy.

Re-reading Starman at different stages of my life is something I’ve been counting on for over fifteen years. I read it as a teen as it was being published. When I approached 30, I tracked down the side stories that Robinson wrote in other books like Showcase ’95 and read the whole thing in publication order. I was Jack’s age then.

Now I’m a father of young boys and I think it’s near time I trot Starman out to see what kind of things I’ll pick up now that I can somewhat identify with Ted for the first time. Same ten years from now when my own kids will be teenagers.

The entire Starman #0 can be found here. It’s classy, it’s cool, and—fair warning—it’ll make you fall in love with Opal City too. If you really do fall in love, there are six omnibus editions that are so gorgeous they’ll make you cry. The Omnibuses even include the copious letter columns where James Robinson goes out of his way to talk antiques and movies etc. with the readership (yes, he’s pretty much Jack), and the Shade’s Journals, which were text-only chapters of pulp-era stories just like Wilde or Dickens would’ve written.

Screw it. I’ll dig out those Starmans before the year’s done.

CDs On Rotation In Our Six-Disk

Bad Religion- Stranger Than Fiction by Bryan O’Donnell

In the Winter of 1994, the alternative rock station in Chicago put on their first “Twisted Christmas” concert. It featured bands that released some huge albums that year, including Weezer, Hole, and Dinosaur Jr. I was fortunate enough to attend the concert, and while I enjoyed those bands, another band stole the show for me: Bad Religion.

That performance cemented Bad Religion as a favorite band of mine for years, but my introduction to the band was their album released in August of 1994, Stranger Than Fiction. The album included two infectious singles, “Infected” and “21st Century (Digital Boy),” which was actually a re-recorded song from earlier album Against the Grain. It’s a bit funny to think now that a two-minute-song punk band like Bad Religion would get any radio play, but these songs actually got a decent amount of air time.

Top to bottom, it’s hard to find a bad song on Stranger Than Fiction. Lead singer Greg Graffin rolls out unique lyrics that make you think about the hypocrisies of society and government. And he’s a master of the metaphor and description—in “Individual,” he sings, “Urbana is oozing like a bloated carcass, with maggots cooking in the desert heat. Oozing, with progeny writhing and desperate for input from someone more determined.”

For a punk record, Stranger Than Fiction features a nice amount of melodic moments and ripping guitar solos. The album features a couple of guest appearances from Tim Armstrong (Rancid) on “Television” and Jim Lindberg (Pennywise) on “Marked.” Probably my favorite song of Stranger Than Fiction appears near the end of the album, “Inner Logic.” How about this for an opening few lines: “Automatons with business suits clinging black boxes, sequestering the blueprints of daily life. Contented, free of care, they rejoice in morning ritual as they file like drone ant colonies to their office in the sky.”

I was years away from college in 1994, but looking back now, I can see why I loved this band—and album–at the time: I feel like Bad Religion is the punk band for English majors. If Stranger Than Fiction snuck past you during the jam-packed 1994, make sure to go back and give this one a chance.

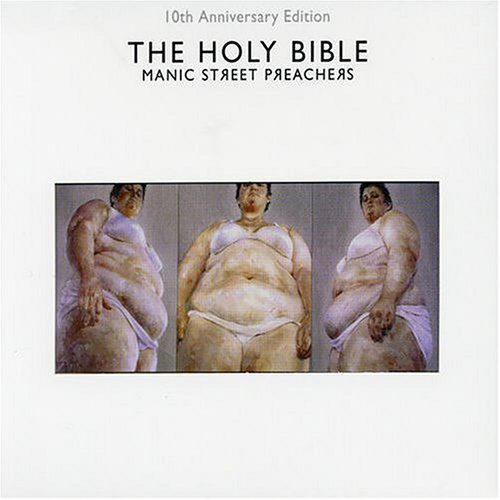

Manic Street Preachers- The Holy Bible by Abbie Sears

It was once said by Tom Ewing, a writer for Freaky Trigger, that “Writing about The Holy Bible without somehow addressing the vanishing of Richey Edwards would be pointless: you would only be tracing his outline as you gradually and gingerly tiptoed around it.” This is absolutely right. Richey Edwards was a guitarist and lyricist for the Manic Street Preachers, and he disappeared in February 1995. The Holy Bible is the last album he worked on. For this reason, it is a hard listen. When you know the history and the trauma that he had been experiencing during the recording of this, you can feel every word that he wrote and relate it back to his own state of mind.

It was once said by Tom Ewing, a writer for Freaky Trigger, that “Writing about The Holy Bible without somehow addressing the vanishing of Richey Edwards would be pointless: you would only be tracing his outline as you gradually and gingerly tiptoed around it.” This is absolutely right. Richey Edwards was a guitarist and lyricist for the Manic Street Preachers, and he disappeared in February 1995. The Holy Bible is the last album he worked on. For this reason, it is a hard listen. When you know the history and the trauma that he had been experiencing during the recording of this, you can feel every word that he wrote and relate it back to his own state of mind.

The Holy Bible has often been named one of the greatest albums of all time, and it is brilliant, but it is also incredibly dark. Something I like about this album is that the vocals seem to stand out from the music. A lot of the time vocals and music blend together and form a nice tune, but The Holy Bible offers something that feels so raw. You hear the music, that the band bought back to its British roots for this particular album. Then James Dean Bradfield’s vocals come in almost on another level, covering topics like anorexia, drugs, self-harm and death, everything that filled Richey Edward’s mind while he wrote the lyrics came out through the music. Listening to the band perform these words makes me question whether they were comfortable to do so, seeing Richey passed out on the couch as they recorded his words in the studio, did it ever feel like a bad idea to keep turning this into music?

I’m glad that they did. This album is one that educates it’s listeners and certainly opens your eyes to a slice of reality. As a fan of the band or of rock, or even music in general, everyone should take the time to listen to this album and really listen to the words, it’s one thing to realise how awesome the music is but to analyse the feeling behind each line is a completely different experience and that’s how you truly appreciate what you have in-front of you. 25 years since this album was released and it is still known across the United Kingdom as an all time classic and still is often given the credit it deserves. It may always remain a mystery what exactly happened to Richey but The Holy Bible is something he left behind for us which I see as an insight into what he experienced during his final year in the public eye.

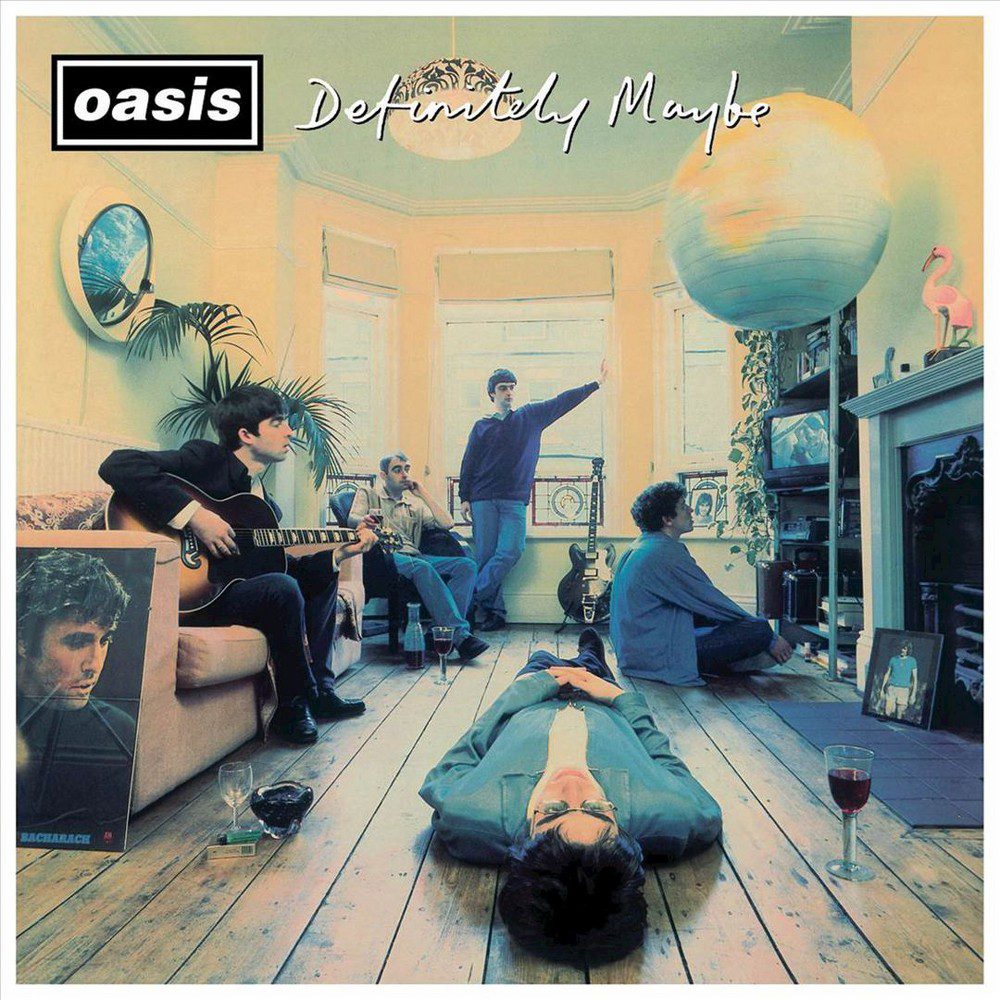

Oasis- Definitely Maybe by Chris Flackett

If you weren’t a child or teenager growing up in Britain in the mid-nineties, you might find it hard to understand why the pedestal still gets erected for Oasis, years after a run of fair-to-middling ‘noughties’ albums and a very messy brotherly split.

But if you were growing up in the mid-nineties, you’ll know exactly why. You remember the immediate sugar rush of those massive singalong choruses, the hilarity of the nonsense arguments between the brothers Gallagher, and you’ll remember just how bloody good those songs sounded blasting out of your radio whilst out in the sunshine.

For a small period of time, a few years at least, Oasis were the biggest band in Britain since The Beatles and The Stones, easily, no matter how crazy that statement might seem in hindsight.

Definitely Maybe is where it all began, and its no wonder that Oasis kept calling every subsequent album ‘the best since Definitely Maybe.’ This was an album with nothing to lose and an insane amount of self-confidence.

Growing up in working class Burnage in Manchester, pop music gave the Gallagher brothers a reason to be. For Liam, it was merely the idea that being a rock ‘n’ roll star, in the old fashioned sense, with all the attached heroisms and swagger, was exactly how your life should be lived. You could imagine Liam being a bin man and still carrying himself in every way as a rock star.

For Noel, he saw music as a way out of his situation, a way to better himself, not only in the escapism of listening, but in the transformative acts of writing and playing. He had enough of feeling he was being limited in his potential by his background and took up the guitar as his weapon to transcend it with.

When the two philosophies collide, as they do all over Definitely Maybe, it results in some of the most thrilling pop music ever recorded, the two complimenting and taunting each other to ever greater heights.

Rarely has such simple, immediate songwriting outside of punk been so bracing. Here was the Beatles being covered by the Sex Pistols, by way of Manchester, throwing the Buzzcocks, the Stone Roses and The Who into the melting pot for good measure. The resulting wall of sound defies taste and logic – the music is larger than that, and people forget how loud this album can be, thanks to the production duties of Owen Morris.

The key track? “Live Forever.” Over a yearning, anthemic melody liberally “borrowed” from “Shine A Light” by the Stones, the band essayed a song about being alive that made you feel glad you were alive. For Noel, it was about how you cannot be who you want to be without a strong will and self-belief, how you must kick doubt to the curb. For Liam, he didn’t want the ecstasy of being larger than life to end. Ever. Why live any other way?

“Tonight, I’m a Rock ‘n’ Roll star.” Amen, brothers.