“I am tired and sick of war. Its glory is all moonshine. It is only those who have neither fired a shot nor heard the shrieks and groans of the wounded who cry aloud for blood, for vengeance, for desolation. War is hell”.

— Union General William Tecumseh Sherman

Has there ever been a more relevant and powerful quote as “War is Hell”? It can apply almost anywhere and be translated endlessly because, sadly, war is a universal language. And though war movies are known to be, at their best, heightened reality and a safe space where we know, in the end, what we are seeing isn’t real, a lot of the truly great war films can still manage to tap into that visceral and haunting reality of conflict that only a select few, in reality, experience.

For my generation, born in the late ’70s and early ’80s, a time when we were still too young to fully grasp Apocalypse Now or The Deer Hunter, Saving Private Ryan was perhaps the most popular and widely available look at war at its most horrific. Though I inappropriately grew up on horror films, seeing the violence in Saving Private Ryan with full sanction from my parents (I was still under 17 at the time) and assigned to such a prestigious “real” film had an immense effect on me as a viewer, especially during my film coming of age, for lack of a better term.

While I wouldn’t say war films are my go-to genre when choosing something to watch, I do tend to find myself leaning towards war films when they tap into how war affects humanity on a psychological level, while still providing Saving Private Ryan’s gripping realism. For example, in the same year Saving Private Ryan was released, I forced a lot of my friends to go watch Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line with me, a film I did, and still do, prefer over Ryan.

The Thin Red Line did have war sequences and moments of uncomfortable violence but at its core was poetic narrative; trying to find a method to the madness or, at the least, a reason to stay sane long enough to escape said madness. While Ryan had Spielberg’s grand touches (but also an impressive maturity only seen from time to time at that point in his career) that made my eyes open and my heart soar, The Thin Red Line went deep into my subconscious and began fomenting a philosophy.

As someone who has not, and probably will not, see war first hand, I can only examine it through stories. As is the case with many war films, especially ones based on history itself, the stories of war are timeless and never-ending, in which man must go beyond its own instincts to harm another man ad nauseam. The effect that has not only the specific war in question but on the ethics of humanity itself days, years, and centuries after the fact is what truly interests me.

When it was time to do my monthly Criterion deep dive, I wanted to look at war films and, more specifically, to see how the depiction of war varies (or not) when presented from a worldview outside of my own. The inspiration of this is no doubt due to Letters From Iwo Jima, my absolute favorite film about warfare that, though directed by an American (Clint Eastwood), was incredibly faithful to the source material (actual letters written by a Japanese general who was well aware his death was imminent) and that portrayed the “enemy”, for American audiences, the Japanese, in a neutral light, depicting their struggles without intent and giving their characters dimension.

Presented below are six “modern” war films available on the Criterion Channel, depicting significant wars from 1899 to 2006. Featuring fictional World War II films from Poland and Japan, as well as a documentary from the United States, I wanted to promote films that showed viewpoints of that conflict from the occupied/liberated, the defeated, and the victors, respectively. Add other entries from Soviet Russia, Australia, and France, depicting wars in Asia and Africa, this short but wide-ranging guide will hopefully show how war, and its effect on humanity, is felt across five continents and throughout time.

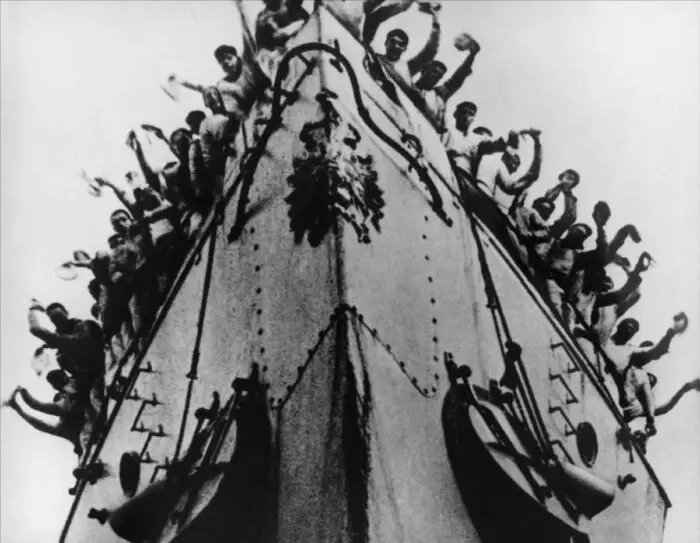

Battleship Potemkin (1925)

“Shoulder to shoulder. The land is ours. Tomorrow is ours.”

Director: Sergei Eisenstein

War: The Russian Revolution (1905, Soviet Perspective)

Story: Sailors on the Russian battleship Potemkin become disenchanted by their poor treatment from their superiors, be it violent outbursts or by being forced to consume rotten food. With Revolution brewing on the Russian homeland, fed-up sailor Vakulinchuk begins his own mutiny on the ship. While the officers are successfully removed, Vakulinchuk dies.

Vakulinchuk’s body, now positioned on the shores of Odessa, becomes a literal symbol for the cause of freedom, becoming an unknowing catalyst for change. The public begins their own revolution against Odessa’s ruling class as the Potemkin, now free, surges face-first into combat with other battleships on the open sea. Will the crew of the Potemkin defend their freedoms or perish for the cause?

Thoughts and Analysis: Eisenstein was a champion of the montage and Battleship Potemkin is a shining example of how that manipulation of storytelling works to ramp up emotions that are usually dampened down by the (now) poor technology of the ’20s and the lack of dialogue and sound effects. Silent films have their own power, of course, as anyone who has seen The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari can attest, but an innovative technique like creative editing can do so much more for a picture.

Battleship Potemkin, like many Soviet-era films, can be accused of being propaganda. I do not know enough about the Russian Revolution to say one way or the other whether Battleship Potemkin is her worship or a faithful retelling of how change came to the people. One thing is for certain though: people love underdog stories in any form and the abused and neglected sailors of the Potemkin are worthy of our sympathy.

Though the majority of the film revolves around the sailors and their successful mutiny, the film’s most memorable sequence is the act entitled “The Odessa Steps”, a scene in which Tsarist-loyal Cossacks put to rest the civil commotion spurred on by the Potemkin’s moral stand. As expected, a fully armed military unit lays waste to the unarmed and unprepared civilians, in a scene shockingly gory and relentless, especially for something coming from the ’20s.

While revolution itself is a strong enough storyline to carry the day, it is “The Odessa Steps” that shows the horrors of war when it afflicts a defenseless population, armed only with ideas which, sadly, when confronted with force, can be so casually dispatched.

If You Want More Eisenstein: Five additional Eisenstein solo directorial efforts appear streaming on the Criterion Channel, including the historical epic Ivan the Terrible, Part 1 (1944) as well as his first feature-length film Strike (1925), which, like Battleship Potemkin, deals with worker’s rights and revolution. The wild-haired Soviet director died at the fairly young age of 50 in 1948 but still had films coming out after his death, such as Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 (1958), which was only delayed due to a ban by Joseph Stalin himself, who ironically requested the film be made in the first place), and two documentaries revolving around Mexico that were released in 1958 and 1979 respectively.

Bonus Features on Criterion for Battleship Potemkin: none

Availability: Battleship Potemkin is only streaming on the Criterion Channel and is not assigned a spine #.

Ashes and Diamonds (1958)

“Do you believe in all this?”

“Me? That’s of no importance.”

Director: Andrzej Wajda

War: World War II (1939-1945, Polish Perspective)

Story: May 8th, 1945: the last day of World War II for Europe. But it’s the beginning of endless upheaval in a fragile Poland. The energetic and young Maciek Chełmicki (Zbigniew Cybulski) and his commanding officer, cold and calculating Andrzej (Adam Pawlikowski), are Home Army soldiers and veterans of the Warsaw Uprising, who have traded fighting Nazis for Communists. After an attempted hit on the Polish Worker’s Party representative Konrad Szczuka (Wacław Zastrzeżyński) goes horribly wrong, Chelmicki and Andrzej regroup and plan the assassination again, this time at the bustling Hotel Monopol, where Polish men and women of all stripes are celebrating the end of the massive conflict.

Though Chelmicki ends up getting a hotel room directly next to Szczuka, his dalliance with a young bartender named Krystyna (Ewa Krzyżewska) and an endless night of drinking has him not only questioning his current mission but wondering where the continued violence, under different banners of ideology, will lead him.

Thoughts and Analysis: The America viewpoint of the end of World War II was unique compared to almost every other country involved in that great conflict. While “our boys” were coming home to a virtually untouched homeland, occupied countries had to readjust to freedom and pick up the pieces of literal destruction while fallen enemies had to come to grips with their crimes.

Ashes and Diamonds is such a great film because it accurately portrays that the declaration of the great war ending doesn’t immediately stop the upheaval and change for those literally in the middle of the action. As Ashes and Diamonds wisely shows, Poland was a wild card when the war came to an end: resistance cells and Communist sympathizers co-existed in a country still trying to recover not only from Germany’s initial Occupation but the Russian’s governmental infiltration.

The film spends most of its time at the Hotel Monopol where the film’s protagonists, members of the resistance movement, mingle with communist party leaders, government sympathizers, and the general public, who are just happy the war is over. It is this small scale depiction of clashing ideologies that help explain Poland on a larger scale: the war was over but the fight for identity was just beginning.

In 2018, the film Cold War focused on a similar period in Poland’s history and appears to be influenced, at least partly, by Ashes and Diamonds. If anything, Cold War takes a lot of visual cues from Ashes and Diamonds’ crisp cinematography and tense atmosphere. Zbigniew Cybulski, the energetic lead of Ashes, and considered the “James Dean of Poland”, is so emblematic of that chaotic time: antsy, energetic, nostalgic, fearful, defiant, and in need of confirmation that what he is doing is the right thing. But, in the end, in that quagmire of mixed ideology and raw emotion, what exactly is considered right?

If You Want More Wajda: On the Criterion Channel, three additional Wajda films are available, including A Generation (1955) and Kanal (1957), both about resistance and survival in Nazi-occupied Poland. Wajda was given an honorary Oscar in 2000 and directed films up until his death at the age of 90 in 2016, including the Academy Award-nominated films Katyn (2007), about a Soviet atrocity against a Polish community, and The Promised Land (1975), about factory life in turn of the century Poland.

Extras on Criterion for Ashes and Diamonds: a 2003 interview with Wajda, fellow Polish director Janusz “Kuba” Morgenstern, and Polish film historian Jerzy Plazewski; a behind-the-scenes newsreel.

Availability: Besides streaming on the Criterion Channel, Ashes and Diamonds is available on the Criterion boxsets Essential Art House: Fifty Years of Janus Films (no spine #) and Andrzej Wajda: Three War Films (spine #282).

Fires on the Plain (1959)

“For people like us, living day and night on the brink of danger, the normal instinct of survival seems to strike inward, like a disease, distorting the personality and removing all motives other than those of sheer self-interest”. — from Fires on the Plain, by Shōhei Ōoka

Director: Kon Ichikawa

War: World War II (1939-1945, Japanese Perspective)

Story: As Japan, unknowingly, or at least, unwillingly, inches toward defeat in World War II, Japanese soldiers in the Philippines (amongst other places), struggle to preserve food, keep their boots in one piece, and hold any strategical position as the heavily armed, well-fed, and overpowering Allied forces surround them on all sides. Units and platoons are now reduced to squads of two or three and soldiers are scattered in the wilderness, looking for any haven to find salvation.

One such soldier is Private Tamura (Eiji Funakoshi), who, suffering from tuberculosis, is kicked out of his unit as too sick to serve and a waste of resources. But the Army hospital won’t take him as he isn’t sick enough compared to the heavily wounded that litter every available floor space. When both his old unit and the hospital are wiped out from air raids, Tamura must roam the farm fields, the jungles, and the rocky desert terrain of the Philippines, encountering friends and foes who, in the desperation of survival, have no sworn allegiance but to themselves.

Thoughts and Analysis: While Apocalypse Now depicted the descent into hell with hyper-realistic images and Saving Private Ryan showed the graphic ultra-violence of armed combat with in-your-face intensity, those films could not have existed without the harrowing, stomach-churning journey of Private Tamura in Fires on the Plain.

It takes a lot to unsettle me as a writer and critic of film and I thought I had seen it all, but Fires on the Plain is so brutal that the term nihilistic seems like cushy flattery. Although made in 1959, based on the book of the same name published in 1951, Fires on the Plain was ahead of its time in depicting the savagery and inhumanity of warfare by depicting it on a claustrophobically personal level. Private Tamura is our unwitting tour guide in what can only be described as a “road movie” into the void.

While most of the gunshots and explosions yield some generally bloodless deaths, as befitting that time in cinema, Fields amplifies the desperation of the Japanese soldiers by putting them in increasingly debased position. One soldier, desperate for food, eats his own feces. Soldiers ransack the dead for shoes with fewer holes than the ones they already have. Cannibalism and humans as sport become a survival technique while even Tamura himself murders an unarmed girl for a bag of salt.

While a number of the films I look at in this column show the ethical conundrum of war, none of the films garner as much sympathy for people doing awful things like Fires on the Plain does. By having our protagonist struggle with his decisions, we too, in the comfort of our couch or comfy chair, do the same, debating and reasoning with ourselves how, when no other options exist, an insane act be the only sane solution.

If You Want More Ichikawa: Ichikawa had an insanely prolific career, directing film and television from 1936 to 2006. His masterful documentary Toyko Olympiad (1965, which I covered in my Criterion review of Japanese Film Directors, Part 1), the war film The Burmese Harp (1956), the light drama Odd Obsession (1959), and the thriller An Actor’s Revenge (1963) are all available to stream on The Criterion Channel alongside another five of his feature-length films.

Extras on Criterion for Fires on the Plain: a 2006 interview with film historian Donald Richie; a 2005 and 2006 combined interview between Ichikawa and Mickey Curtis, who appeared as an actor in Fires on the Plain.

Availability: Besides streaming on the Criterion Channel, Fires on the Plain is available on DVD, spine #378.

Breaker Morant (1980)

“The fact of the matter is that war changes men’s natures. The barbarities of war are seldom committed by abnormal men. The tragedy of war is that these horrors are committed by normal men in abnormal situations. Situations in which the ebb and flow of everyday life have departed and have been replaced by a constant round of fear and anger, blood and death.”

Director: Bruce Beresford

War: The Boer War (1899-1902, Australian/English Perspective)

Story: In the dying days of the Boer War, a majority-Australian contingent of an English special forces-like group called the Bushveldt Carbineers falls into a trap and its leader, Captain Hunt (Terence Donovan), is killed and, later, mutilated by the guerilla-like Boers. When Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant (Edward Woodward) finds the group that killed Hunt on patrol, he has the prisoners executed, following an unwritten rule that prisoners of war are not to be captured as the English do not have the resources to care for prisoners.

When he returns to camp, the wise veteran Morant, along with cynical lady’s man Peter Handcock (Bryan Brown) and boyish newbie George Witton (Lewis Fitz-Gerald) are charged with murder for executing the Boers. Assigned green defense attorney Major James Thomas (Jack Thompson), who is literally handling his first case, the three men recount their alleged crime and slowly discover that their attempted court-martial is less about justice and more about prejudice and politics.

Thoughts and Analysis: I admit, embarrassingly, that I had never heard of the Boer Wars. So Breaker Morant not only gave me a compelling courtroom drama to watch but taught me a little bit more about the history of colonial England than I currently knew. During the time period the film is set, at the turn of the 20th century, Australia was still a part of the British Empire but was becoming and more independent (it is now a sovereign nation). However, after being a part of the Empire for so long, and not always seen as true citizens, Australians dealt with a lot of prejudice from their superiors.

This built-in prejudice is one layer of the complicated premise Breaker Morant showcases to its audience. The unwritten rules of war, as well as the cold-hearted machinations that go into every conflict, color the morals of our protagonists and the concept of duty. “Breaker” Morant and his team are considered uncultured, wild Australians who would, of course, do barbaric deads because, as the British suspect, it is in the Australian blood. This, right away, makes us root for the Australians even though they did, indeed, do some pretty terrible things.

That is the moral complexity Breaker Morant gives you. It presents vibrant, interesting characters who are clearly the victims of unfair prejudice but also people simply following orders that are, in their very nature, ethically bankrupt. So are they forgiven for the crime even if it was technically sanctioned? And what does that do to mankind when unethical deeds are considered lawful?

It is this, and so much more, that makes Breaker Morant an enlightening breakthrough in War cinema. Though the action is light, the endless intrigue of moral conundrums as well as the audience’s struggle to determine who is right and who is wrong makes for compelling viewing.

If You Want More Beresford: Beresford most popular directing effort might be Driving Miss Daisy (1989), which won four Oscars, including Best Picture. Oddly, of Daisy’s nine Academy Award nominations, one wasn’t Beresford for Best Director. However, he had previously scored Oscar nominations for co-writing Breaker Morant and for directing Robert Duvall in Tender Mercies (1983). Beresford has been consistently prolific, directing multiple features in every decade from the ’70s to the ’10s. Other career notables include Crimes of the Heart (1986), Her Alibi (1989), and Double Jeopardy (1999). Beresford’s period drama Mister Johnson (1990) is available to stream on The Criterion Channel.

Extras on Criterion for Breaker Morant: feature-length commentary by Beresford; a 2015 interview with Beresford about the film; a 2015 interview with the film’s cinematographer Donald McAlpine; a 2015 interview with one of the film’s stars Bryan Brown; a 2004 interview with Morant actor Edward Woodward; a 2015 interview with historian Stephen Miller about the real Second Boer War and the film; the 1973 documentary The Breaker, about the real-life “Breaker” Morant; a short interview from 2011 with The Breaker director Frank Shields.

Availability: Besides streaming on the Criterion Channel, Breaker Morant is available on Blu-Ray/DVD, spine #773.

George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin (1994)

Director: George Stevens Jr.

War: World War II (1939-1945, Allied Perspective)

Story: George Stevens, a prestigious film director in the 1950s (Giant, Shane, The Diary of Anne Frank), served in the Army during World War II. Too old for combat but a veteran of Hollywood, Stevens was assigned as head of a special film unit with the mission of documenting the war for the American public. His black and white footage of the European theater went to Newsreels in the United States and put a public face on the war. But Stevens also filmed his own personal footage of his experiences in Europe, unknowingly, uncensored, and in color.

Stevens’ son George Jr. discovered the color footage well after his father had passed in 1975 and, as a result, not only submitted the rare film to the Library of Congress but put together this movie which shows Stevens’ hauntingly real look at war-time Europe, starting with the beaches of Normandy, to the Liberation of Paris, and, at the end, the occupation of Berlin. While the Newsreels showed the boys fighting the good fight, Stevens captured the boredom, sadness, destruction, and, most importantly, the death involved in an unforgiving conflict.

Thoughts and Analysis: D-Day to Berlin’s greatest strength lies in explaining that the war was presented to the majority of the world as a digestible product of dramatic storytelling and intrigue. Yes, lives were at stake, but for American’s viewing the “highlights” via News Reels, the true effect of endless death didn’t quite hit home.

Though George Stevens likely never intended for his personal footage of the war to be released to the public, its contradicting nature compared to the News Reels put World War II in shocking perspective. D-Day to Berlin has a wide range of images to show, many of them unique and even charming, such as soldiers opening up cards from home or horseplaying with each other when bored. But it also serves to end the mythic qualities of both some historical figures and death itself.

For example, in one sequence, we see General George Patton hanging around a base camp, randomly talking with other soldiers and laughing, looking slightly hunched over and older. What you’re not seeing is the chest-out, gung-ho, severe general of legend. He appears to be just a man and one simply laughing, not snarling. In a scene involving the mass surrender of Nazis, a look into the crowd doesn’t show the enemy made entirely of 6′ 2″ blond behemoths with leather dusters, jackboots, and snarls but, rather disenfranchised youths and confused soldiers, who, despite representing a terrible ideology, appear all too human.

But the most important part D-Day to Berlin has to play is in the depiction of death. The film does not edit out the scenes of carnage and, by doing so, it provides something much deeper and terrifying in regards to what human life looks like when it is suddenly gone. The bodies, for instance, are quite as torn apart and mangled as many fictional films portray. Instead, the body is still mostly intact but the eyes are blank and one can see the soul, if you believe in such a thing, as left, leaving a literal husk. It is sobering, especially sequences where Stevens witnessed the liberation of Dachau (be warned if watching, the footage is immensely unsettling).

It might not make for the most cheery family entertainment but George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin is something grander than just skilled movie-making: it is truly important and necessary storytelling.

If You Want More Stevens Jr.: Stevens Jr. directed a few TV episodes and documentaries but was mostly known as a writer and producer. His largest contribution to film may be the founding of the American Film Institute. He also co-created the Kennedy Center Honors.

Extras on Criterion for George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin: an interview with director George Stevens Jr.

Availability: George Stevens: D-Day to Berlin is only streaming on the Criterion Channel and has not been assigned a spine #.

Flanders (2006)

Director: Bruno Dumont

War: Unspecified Middle Eastern Conflict (The ’00s, French Perspective)

Story: Farmer Demester (Samuel Boidin) has been deployed to the Middle East. A man of few words and emotions, Demester’s days leading to his deployment were uneventful, mired in menial farm labor and quick, silent sex with his psychologically damaged girlfriend Barbe (Adélaïde Leroux). However, once in a foreign land, Demester’s life becomes anything but boring.

In a unit with other disassociative youths from his small hometown, Demester must deal with an unforgiving physical environment, sneak attacks by villagers of all ages, and his own baser instincts. With Barbe at home slowly deteriorating (and pregnant to boot), Demester meanders through a world of murder, rape, torture, and the concept of honor all while trying to stay alive even if there is nothing worth living for.

Thoughts and Analysis: Unlike most of the films I’ve reviewed in these monthly Criterion columns, Flanders is probably the only one I have outright loathed. Though it shares the same themes of both Fires on the Plain and Breaker Morant, showing how war is, at its essence, inhumane, Flanders brutally nihilistic approach feels unearned and unwarranted.

In Fires on the Plain, we had Private Tamura who, at his core, is a good person thrust into an impossible situation. He struggles with his acts of cowardice, revulsion, and murder, contemplating why he wants to go on living when he has lost so much on the inside and out. In Flanders, our “hero”, Demester, is already an empty shell, devoid of feeling or morals, outside of a warzone so when he engages in atrocious activities in the mouth of war, such as raping a female enemy combatant, simply because he feels like it, there isn’t any actual character evolution there.

Is he suddenly enraged at the hell around him that he must punish the enemy for firing at him? Or is Demester simply a debased human being from the start who would have raped the woman anyway? Flanders offers no point of reference for Demester’s reasoning and actions and, in turn, that dulls the message Flanders might be trying to send about war.

At some point, it feels like director Dumont is simply hoping the depiction of graphic barbarity will drive some sort of message home. Instead, it feels like, for lack of a better term, torture porn. We feel revulsion when a man is castrated in front of us but only because the act itself is gross, not because it appeared for any thematic purpose other than to sicken the audience.

There may be an audience for this type of film but I find its lack of compelling philosophy, two-dimensional characters, and violence for violence sake a waste of a visually competent filmmaker’s abilities and, most importantly, an audiences time.

If You Want More Dumont: Dumont is considered one of many directors involved in the film era called the New French Extremity. And while Flanders is certainly not as visceral or as raw as, say, High Tension (2003) or Martyrs (2008), Dumont’s nihilistic sensibilities in Flanders does make its place in the NFE movement seem legitimate. Five additional Dumont films are available on the Criterion Channel, including L’Humanité (1999, which won the Grand Prix at Cannes and was nominated for the Palm d’Or) and La Vie de Jesus (1997).

Extras on Criterion for Flanders: none

Availability: Flanders is only streaming on the Criterion Channel and has not been assigned a spine #.

Please join me in October when I look at the Criterion Channel’s Animation selection. And in November I’ll be exploring the Criterion vault for Documentaries.

If you are interested in seeing my other columns digging through the Criterion Channel’s streaming offerings, please click the links below:

Also, please check out the site tag The Criterion Collection for individual film reviews of movies both in the physical Collection and streaming on the Channel from other excellent writers here at 25 Years Later.

Lastly, follow me on Letterbox’d so we can discuss what you are watching!