OK, let me rephrase that: Kevin and Michael Goetz’s remake of Martyrs (2016) is good, and let me tell you why. I know what you must be thinking—she’s being a contrarian for the hell of it. But hear me out. First, what makes a film good? We all know this is subjective, but what do I mean when I say the 2016 remake of Martyrs is good? Well, let me tell you. The standard by which I judge it needs to be clearly defined, so here goes nothing.

In his January 2016 review of the Martyrs remake in Bloody Disgusting, Trace Thurman wrote, “It is difficult to review Martyrs without comparing it to Pascal Laugier’s phenomenal 2008 film of the same name.” Paired with Nina Nesseth’s take on the merits of remakes written for Nightmare on Film Street July 2019, I took these pieces of wisdom as my guiding principles: to see the remake on its own and not strictly in comparison to the original.

Thus, rather than spend the rest of this piece constructing a list of similarities and differences between the two films (which you can find elsewhere on the internet), I want to focus on two interrelated points from translation theorist André Lefevere: the purposes and expectations of translation. [1] I know, I know—BORING! But I promise the suffering is worth it. Bear with me.

“In making decisions, translators should remember that their first task is to make the original accessible to the audience for whom they are translating.” [2]

Let’s see what Mark L. Smith, the remake’s screenwriter, has to say about this: “I tried to stay away from all the violence and keep it off-screen, which was kind of the polar opposite of the original. I know a lot of people love it, but that isn’t what I wanted to do. I think people are probably right when they say it’s ‘Americanized.’ The cultures are different to some extent…” [3]

I can picture you now, rolling your eyes so hard that they may fall out of your head. “Look, Tara,” you say, “American horror films are plenty violent. Haven’t you ever seen, I don’t know, House of 1000 Corpses? Murder-Set-Pieces? [enter title here]?” Yes, no, and it’s possible. And I hear you, reader. I really do. But I don’t think the violence in those films is the same as what appears in the original Martyrs (2008). Or, in other words, it doesn’t serve the same purpose. Let me explain.

That Laugier’s Martyrs is a so-called transgressive work, evocative of the amorphous subgenre known as New French Extremity, is undeniable. [4] Alexandra West describes these films as “present[ing] what is uncomfortable, not talked about or forgotten, and the horrifying implications of being forced to forget.” [5] While this act of collective forgetting (or remembering) is not particular to the French people, at the same time it is the thread that ties many of these films together. And while Martyrs may not explicitly evoke such dreadful memories of the Vichy government during the Second World War or the horrors of colonialism, it more implicitly struggles with a Catholic identity that is buried deep within France’s (and Laugier’s) bones.

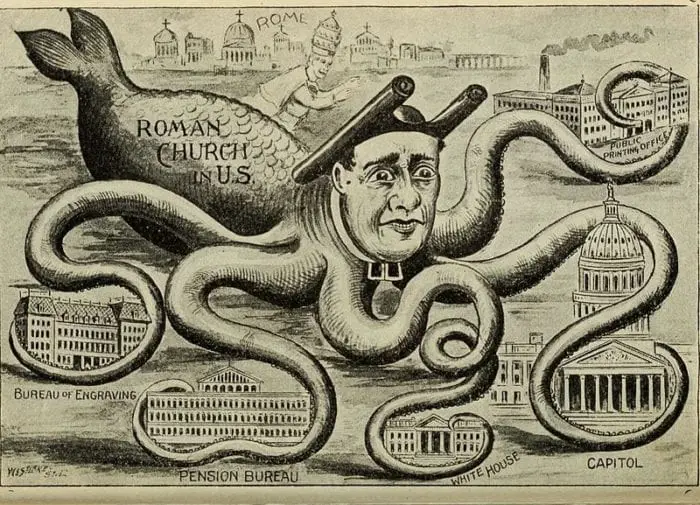

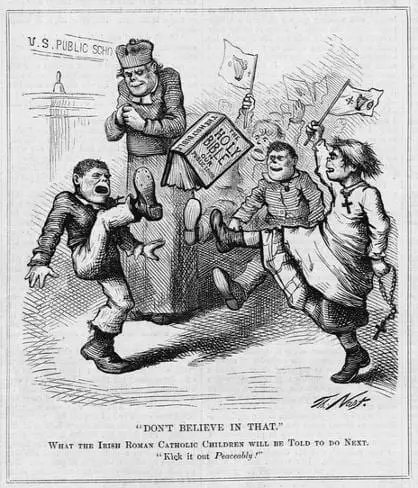

The same cannot be said of America, whose relationship with Catholics is decidedly more tentative. All one has to do is look to the rampant anti-Catholic sentiments during and after the waves of immigration from largely Catholic European countries during the nineteenth century in order to understand this. A good visual aid for grasping these deep-seated fears are the various political cartoons that depict Catholicism as a menacing octopus that will wrap its tentacles around American institutions like the public school or the government or the depiction of Catholic children as monstrosities that are pleased to kick the Protestant Bible.

For an American audience, then, this ideological struggle might be lost on them or certainly would not be as compelling. And if your intention is to make a film that connects to your audience, you wouldn’t necessarily try to speak to them in an idiom that was foreign to them.

If this is the case with the remake of Martyrs, which I argue it is, then you’d have to shift the focus to something else. Smith did just that. For him, the remake is about what attracted him to Martyrs: “the relationship between the two girls [which] started at a young age, and what you’re willing to do for your best friend.” [6]

And the remake hits this home in a number of ways: there’s about five minutes more at the beginning of the film establishing Lucie and Anna’s relationship and time in the orphanage; Lucie doesn’t kill herself halfway through the film but is instead re-imprisoned along with Anna; Anna goes on something of a rampage to free Lucie; they die together in a state of ecstasy.

Would any of this make sense for Laugier’s film? Probably not. After all, what lies at the heart of the original is his sense that “since the world is increasingly divided between winners and losers, what is left to the losers but to do something with their pain? Deep down, it’s what the film is about.” [7]

What the martyr ‘does’ with their pain is buried in the definition of the word that Laugier shows at the end of the film: the Greek word μάρτῠς (martus) means “witness.” To be a martyr is to bear witness to something. As words are never static, we don’t have to say that Christians have the market on the word, either, as its use pre-dates the first/second century CE. So if Laugier’s martyrs bear witness to their pain, what do Smith’s martyrs bear witness to?

To answer this, let’s turn to something else Lefevere has to say about translations: “If [translators] are to mediate effectively between their audience and their texts, they have to attach greater importance to the poetological [Fr., poétologique] and ideological expectations of the target audience than to the poetological and ideological considerations that influenced the production of the source text.” [8]

Getting at the audience’s exact expectations is certainly difficult. But with the repeated use of flashbacks to Lucie and Anna as children (running in a field, playing at the orphanage on the playground, making promises to each other in a church sanctuary, etc.), the expectation that they will end up together, no matter the outcome, is practically foretold. Frankly, it would be strange if they didn’t.

The remake does not end on the suicidal outcome of Mademoiselle’s realization that there is most likely nothing beyond the grave, either. Instead, it ends on Anna lying down to die with Lucie, which fits with the ideology of the rest of the film. The emphasis, as seen in the ending in particular, is not on the martyrs bearing witness to suffering, but on the strength of their communal bond and commitment to each other.

While you may complain that this ruins the original intent of the film, I’d ask you what the point of doing a direct remake would be (maybe in the vein of Michael Haneke’s Funny Games [1997 Austrian original and 2007 America remake]). There are merits, sure, but I think having an interpretation that takes the original in new directions can be just as rewarding. Moreover, if we take Nesseth’s apologia for remakes to heart, we might consider the 2016 remake as an alternate universe, one that underscores kinship instead of isolation.

Interestingly, a remake also gives us a new perspective on the original. In this case, I had only seen Laugier’s Martyrs once, about seven or eight years ago. I had remembered the plot for the most part. For this piece, though, I ended up watching the remake first, followed by the original. In this order, the differences in the cinematography, tone, and focus of each film were made even starker. In some sense, it became clearer to me that at the end of the day, these films are doing very different things and for very different reasons.

While the remake focuses on their relationship in (mostly) positive ways, Anna’s relationship with Lucie is one “of destruction” that, at times, almost seems peripheral to the story in the original film, with the exception that it’s the catalyst that brings Anna to the house and to her eventual demise. [9] At the same time, the isolation and torture experienced by Anna (and Lucie) are nearly absent in the remake, making the repeated episodes of torment more powerful in the original and perhaps making Laugier’s comments all the more horrifying.

That said, I’m not sure that you can deny that the remake doesn’t successfully meet its aim of being a re-imagining of the original. So let’s come full circle: the remake of Martyrs is good. I make this claim because it accomplishes what it sets out to do. It doesn’t want to be the original, and it’s not trying to be. The point is whether you find that compelling enough to give the remake its due.

[1] For example, see The Dead Walk’s April 2019 piece on the two films in their Versus! Series.

[2] André Lefevere, Translating Literature: Practice and Theory in a Comparative Literature Context (New York: The Modern Language Association of America, 1992), 19. Yes, I’m aware that Lefevere is mainly talking about texts here, but I’m playing with his ideas. Sue me.

[3] Christopher McKittrick, “‘I think he wanted to toss me off the cliff’: Mark L. Smith on The Revenant and Martyrs,” Creative Screenwriting Magazine, January 2016.

[4] Though James Quandt seems to have given birth to this term in his 2004 essay “Flesh and Blood: Sex and Violence in Recent French Cinema,” he has also critiqued it in a later essay published in Tonya Horeck and Tina Kendall’s 2013 edited volume The New Extremism in Cinema: From France to Europe. Quandt’s afterword, titled “More Moralism from that ‘Wordy Fuck,’” sees him considering the term something of a misnomer.

[5] Alexandra West, Films of the New French Extremity: Visceral Horror and National Identity (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Company, 2016), 8. For more on the genre, see Matt Armitage’s “Method Behind the Madness: New French Extremity,” found on Film Obsessive.

[6] McKittrick, “‘I think he wanted to toss me off the cliff’: Mark L. Smith on The Revenant and Martyrs.”

[7] West, Films of the New French Extremity, 150.

[8] Lefevere, Translating Literature, 19.

[9] For a powerful consideration of the toxicity of Anna and Lucie’s relationship, see Danielle Ryan’s “How A Horror Movie About Trauma Made Me Realize How Toxic My Friendships Had Become.”