Let me start with a confession (there’s no other way around it): I am not an unconditional fan of Lost. In fact, as far as the work of Damon Lindelof, one of Lost’s main showrunners, is concerned, I think The Leftovers (where this article has taken its title from) is not only better than Lost, but it’s possibly in my top ten TV dramas of all time. At time of writing, I have only seen the pilot of Watchmen, but there is so much potential in just that one episode that I’m very excited for the future.

Lost was essentially my gateway into Lindelof’s work and for that I’m eternally grateful. In fact, overall, I think the show is very good. But I do not think the show is flawless, not by a mile.

So what’s my problem with Lost? To be clear, I really loved the first three seasons. I thought the balance of mystery and character relationships was relatively equal and the story being told was strong.

It was with the fourth season onwards that the show lost its way for me. Concepts (flash-forwards, flash-sideways, time travel, altering the future by detonating a hydrogen bomb) began to suffocate and make claustrophobic the mysteries that so appealed to me at the start. The symbolism became even more overwrought with The Island as the source of the world’s “light” or energy, and Jack’s sacrifice to redeem himself and to save The Island and possibly the world—a surprisingly Christian concept in a show that, in its latter half, showed a strong predilection for quantum physics.

It’s not that I didn’t care about the characters or their wants, desires, and relationships (I was especially glad that Charlie and Claire found each other again at the end). And it’s not that I’m against highly conceptual themes in TV or film. I’m a Pasolini fan, for god’s sake.

What really appealed to me about those first three seasons was the deliciously slow build, but more importantly, it was the mystery of the show—not only what The Island is, but what the crash survivors found there and how. There was an inclusion of the audience into the cast that made us complicit in making discoveries about The Island alongside the characters, which was truly invigorating. As we discovered more and more strange things about The Island, the sense of mystery only deepened, like a hidden pool of warm moonlit water for us to luxuriate in. I hadn’t experienced this with a TV show since Twin Peaks. Like a good hit, I wanted it to last. To paraphrase Meatloaf, three out of six seasons ain’t bad, and I know I’m probably in the minority in feeling this way about Lost. But what it gained in complexity it lost in its seductive mystery, and I don’t think it was worth it ultimately.

But what mysteries am I referring to, and what’s so important about mystery anyway?

A Real Exciting Place to Tell Stories

Mark Frost, writing under the guise of Major Briggs, in his book The Secret History of Twin Peaks, said, “Mystery is the most essential ingredient of life, for the following reason: mystery creates wonder, which leads to curiosity, which in turn provides the ground for our desire to understand who and what we truly are.”

It’s no secret that Damon Lindelof is huge Twin Peaks fan, so perhaps it’s no surprise that Lost shares the concept of mystery with that show. In fact, Frost’s concept of mystery could be applied to Lost very literally: the survivors of Flight 815 experience a sense of wonder at The Island, which evolves into curiosity as they encounter more and more unexplained occurrences (the hatch and the Dharma stations, the Others, the smoke monster, the polar bear, the Adam and Eve skeletons—I could go on for a LONG time). As the survivors discovered more about The Island, its history, and about each other, they were able to satisfy that desire to understand truly who and what they are, culminating in the love, respect, and acceptance of each other as they walked hand in hand into the light at the show’s climax.

Yes, the character dynamics and relationships are ultimately the main focus of the show. But rather than being a show centering on a set group of characters experiencing a mystery, for Lost the mystery itself is the driving force—its Big Bang, the jumping-off point for all character development to flourish from. Without the mystery at the show’s core, the characters would still have developed, but they would not have been perhaps as rich and complex without the mystery to push them forward.

As Lindelof himself has said when discussing other shows in relation to Lost, “the most frightening thing about The Twilight Zone is the idea that we don’t really understand the world as much as we claim to. We claim to these notions of science—and supernaturality frightens us because we don’t understand it. But it is a really exciting place in which to tell stories. We grabbed the reins of that horse and rode it till fell over.” [1]

The Imagination and the Intellect

What is it about mysteries that appeal to me so strongly, and why so in the early seasons of Lost?

I’m a day-dreamy kind of person at heart, so the idea of a mystery appeals to me very much. If the imagination is fed enough quality clues and the right kind of fragments of information, it can build itself a world from a minimum of stimulus. There is great joy to be had in creation, even if it is only the mind (which is the most powerful creator anyway).

David Lynch, of course, is a well-known believer in this “fill in the blanks and create your own world from what you’re given” approach. In Lynch on Lynch, he says, “that there is a mystery is a HUGE THRILL. That there’s more than meets the eye is a thrilling thing…I think fragments of things are pretty interesting. You can dream the rest.” [2]

It was the fragments Lost presented to me that I found thrilling: the distress call from the radio tower, the Hatch and the crazy 108-minute protocol, the capture of Ben as Henry Gale, the secretive “Others,” the Dharma stations, the Cabin supposedly haunted by Jacob, the kidnapping of babies, Locke’s miraculous legs. In my mind, it painted this rich, fascinating world of secret and experiment, with the supernatural lying beneath (and sometimes on top of) the surface. As Lynch said, “There is goodness in blue skies and flowers, but another force—a wild pain and decay—also accompanies everything.” [3]

Were the crash survivors part of an experiment? Had something been awoken that shouldn’t have been? Had a conspiracy been uncovered that was to remain hidden? My mind thrilled at the picture it created, hungry for the next episode to further feed its hunger to daydream.

Mystery can also appeal to the intellect. There is the impulse, certainly, for the mind to make sense of the disparate and irrational and to find its order, even impose an order onto it if one can’t be found. But this is not all. If an order cannot be easily imposed, the intellect will force itself to find and even create links that possibly aren’t there but could be reasoned into existence. The mind, finally out of any other options, forces itself into a different kind of thinking that finds exhilaration in making unexpected leaps of thought.

Whilst this might be a leap of faith towards some sort of definite meaning being arrived at, more importantly, there is joy to be found in the formation of unexpected ideas in and of themselves and also in sharing these ideas. Look at the proliferation of theories that brought communities together online through debate and the development of ideas. The irresistibility of the mystery led to the curiosity of the intellect. In return, the excitement of the ideas generated brought with it the desire to share these ideas with others. Fans began to debate and develop, compare and collaborate on a whole range of theories. In turn, this led to the building of wonderful, passionate communities in love with mysteries, theories, and ideas (just look at our very own 25YL!).

Lost was integral, I believe, in creating and fostering this kind of online community. Yes, there was a fledgling online community around Twin Peaks when it originally aired—fledgling, I’m sure, only due to the limited amount of people who had access to the Internet at the time—and other shows found online attention, but Lost was the first to build such a large, strong online community during its own lifetime, where theories and the love of ideas brought so many people together. Without the mysteries at the heart of the show, Lost perhaps would not have been able to achieve this.

I’ve spoken about the appeal of the show’s early mysteries and the inclusivity of the audience into the cast as the characters made new discoveries, opening up into new mysteries and enriching those that had gone before. But how does this audience inclusivity work?

To answer this, I would like to draw your attention to the feeling I got as I watched those early seasons of Lost as well as another type of media: open-world video games.

The Inclusivity of the Open World

For those not familiar with the term, an open-world game is “a virtual world in which the player can explore and approach objectives freely, as opposed to a world with more linear and structured gameplay.” Classic examples include The Legend of Zelda (1986), Grand Theft Auto III (2001), and No Man’s Sky (2016). While such games can range from completely free exploration to mildly structured with objectives (with some parts of the world only accessible once certain objectives have been completed), the main and most important feature is the ability to explore and discover.

As a viewing experience, a serial TV drama by necessity has to have structure, the narrative being the obvious one. But a mystery allows for a rich interior open world, providing us with clues as we encounter them so that (much as we might whilst playing an open-world game) we establish an idea of the world we are experiencing as we go along, creating a big picture of the world in our heads from the fragments and clues we’re given. The order in which we discover these clues is dictated by the narrative, but the experience of building the bigger picture of the world is one Lost viewers share with open-world gamers.

Building a picture of the world in which the story takes place is very applicable to Lost. From the very first episode, our protagonists, the lucky survivors of a plane crash, find themselves on The Island—an unknown place to them in an unknown location, with unknown terrain and resources to contend with. The characters are as much in the dark about this new world around them as we are.

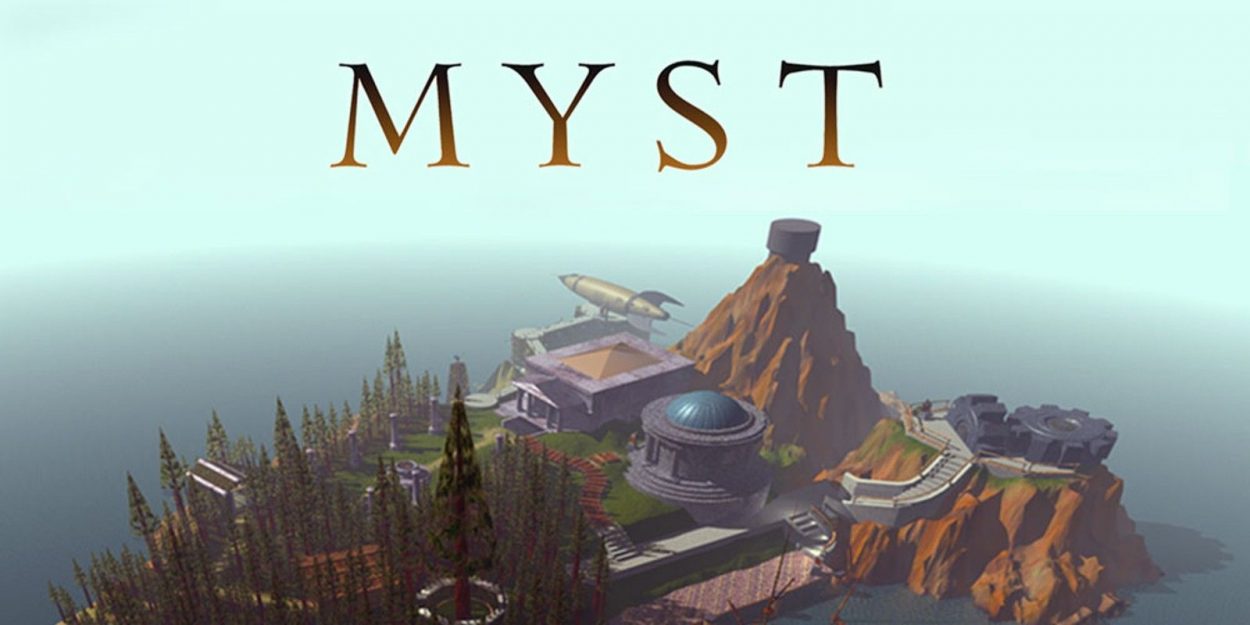

This puts me very much in mind of the classic adventure puzzle game Myst (1993), in which we as the gamers take on the first-person perspective of an unnamed character exploring an unknown, mysterious island. The island is an open world and we are allowed to explore at our leisure. As we explore the island, uncover more information, and complete more tasks, we discover more about the island itself and work towards leaving.

The early seasons of Lost are very reminiscent of Myst in as much as the characters start on the mysterious island with no prior knowledge of its secrets or terrain, and we learn about The Island as it is explored by the characters and they make further discoveries. Yes, there is a distancing from events in that we are concerned here with a TV show and not a game, and as such we cannot control the characters. But because of this we become included instead as an unofficial character, invisible to the others but just as complicit. We see discoveries as the characters make them or reveal them to others.

We’re right there when Kate and Jack discover Adam and Eve in the cave. We doubted or believed, but we were right there when questioning along with everyone else when they discovered the “enter the numbers sequence every 108 minutes protocol.” We were right at the shoulders of Locke and Boone when they found the Hatch and the drugs plane. We sprang the trap with Rousseau when she caught Henry Gale (a.k.a. Ben Linus). We were flung around the Cabin with Locke and Ben by the mysterious Jacob (or so it was claimed). The point is, every time the characters learned, we learned. We were part of the gang. We were included. It wasn’t simply an exercise in the audience learning information at the same time a character did. We were in the thick of the action. I’ve never had such an experience with a TV show (except maybe The Return, but that’s a different percolator of fish). If Lost should be remembered for anything, I think it should be that.

All thanks to a mystery. Would Lost have been the same show without it? No, but not only that, I think it would have been a lesser show. I might be a miserable excuse for a fan for being unable to get fully on board with the show’s later seasons, but I believe the early seasons of Lost are a joy, and that mystery really is the reason.

Don’t just let the mystery be. Dive right in and let it seduce you. You won’t regret it. Promise.

Notes:

[1] John Thorne and Scott Ryan, “Repaying the Debt: An Interview with Damon Lindelof,” The Blue Rose Magazine 1, no. 5 (March 2018).

[2] David Lynch and Chris Rodley, Lynch on Lynch, New York: Faber and Faber, 2005.

[3] Ibid.