Cinema has contributed its fair share of existentialist protagonists to our culture over the years; Humphry Bogart’s “shop-soiled Galahad” [1] portrayal of private detective Philip Marlowe, trying to cling to some sort of decency in the face of a near-all consuming cynicism; Scottie’s haunted obsession in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, unable to live in the present without remaking (literally) an anchor of his past in the form of his ‘dead’ lover Maddie; and Travis Bickle’s disturbing transformation into an avenging angel via his disconnect from accepted societal conventions and illusions. But perhaps there has been no more sad, no more heart-breaking cinematic existential protagonist than Mickey Rourke’s Randy ‘The Ram’ Robinson in Darren Aronofsky’s great 2008 drama The Wrestler.

In Randy, we have a man who is unable to engage successfully in functioning relationships and aspects of ‘accepted’ western society. He cannot handle the 9-5 standard work-life, he cannot form and maintain stable relationships, he pursues but cannot accept love.

Cannot accept love? As we shall see, the love that Randy eventually does accept is essentially a form of self-sabotage, a reliving of past glories, one last ride into the sun like The Wild Bunch before him. For the affection he receives is fleeting, fickle. Suicidal. The film asks the question: is it better to burn out than to fade away? But what conclusions does it reach?

You Don’t Know What You’ve Got ‘Til It’s Gone

Darren Aronofsky was not particularly a wrestling fan, but he had held onto the idea of The Wrestler for a long time:

“When I graduated film school in 90-something—3 or 4 or something, I made a list of ideas for films. And one of them was called “The Wrestler” and it came out of the observation that no one had ever taken a serious look at this yet. It’s such a major phenomenon in the United States. It has such a long history and it’s such a huge, popular sport. And no one’s ever documented it. I think that’s mostly because people hear it’s fake and they think it’s a joke. But for me the whole line of what’s real and what’s fake is-you know-if you’re 250 pounds jumping off the top rope no matter who you are you’re going to feel that, so it’s not really fake. There’s the whole reality happening.”

At the time Aronofsky is talking about, there had started to be a little downswing in wrestling’s popularity – it didn’t help that the WWF was embroiled in a massive steroid scandal at the time. Just prior to this though, and something that would have been very fresh in Aronofsky’s mind, wrestling had experienced a massive boom period, the first of possibly two.

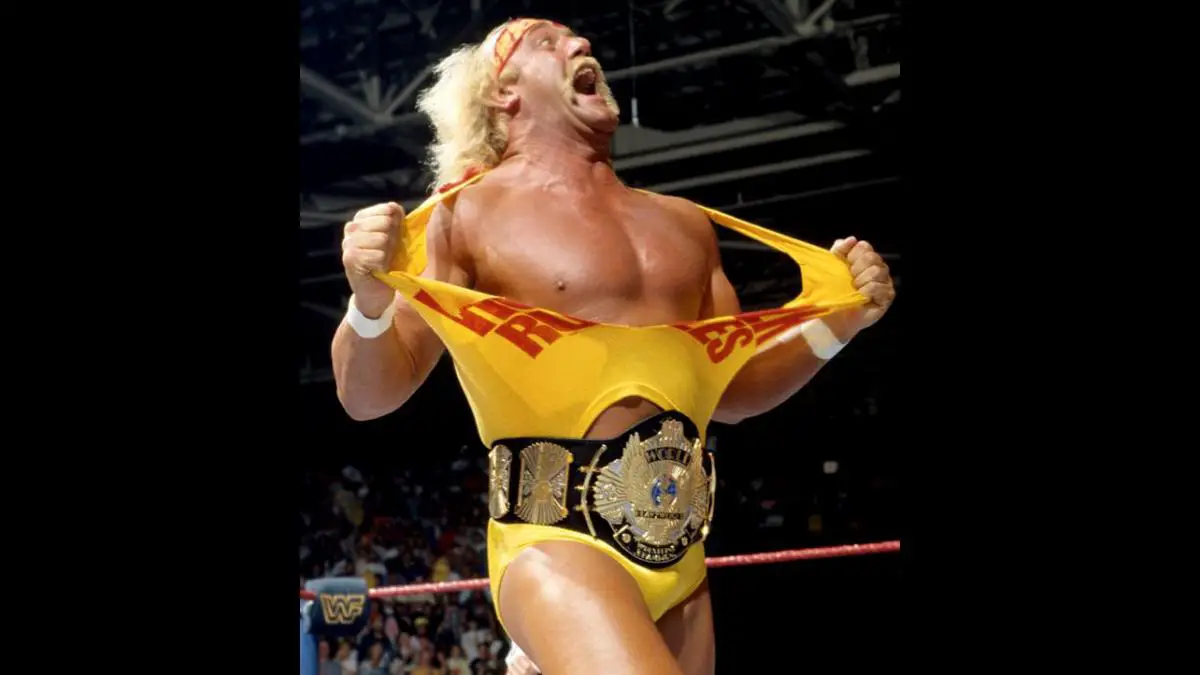

The WWF had ushered in the ‘Rock n Wrestling’ era in the mid-eighties, spearheading a national and eventually global expansion of their business via positive association with some of the biggest celebrities of the time (Mr. T, Cyndi Lauper, Muhammed Ali, even Liberace). Combined with the magnetic charisma of their world champion, Hulk Hogan and a cast of many more OTT larger-than-life superheroes and villains, wrestling became a greater force in the entertainment industry than it had never been before. Wrestlers suddenly had access to much higher paydays than before and with more exposure to the wider public than ever before the potential for crossover activity into other mainstream entertainment outlets was attractive for those whose egos wanted all the fame, power and money it could consume (Hulk Hogan and his movie career, however unsuccessful, being a case in point).

This is the world Aronofsky wanted to explore in the mid-nineties, but by the time he eventually came to make the movie (pre-production started in 2007) the wrestling landscape had changed significantly. No longer was wrestling the mainstream force that it had been, having reached the end of its last boom period in 2001 with the end of the ‘Monday Night Wars.’ The WWE (as the WWF is now known), found itself free of its two major competitors for mainstream entertainment, WCW and ECW. Many fans fell away, disheartened by the lack of choice, the WWE product, and the burgeoning independent scene. While the WWE was still popular globally, it has never since quite reached the heights of its mid-eighties to mid-nineties heyday. This is the wrestling world that Aronofsky inserts his main protagonist into, to use the then-present to comment on the hot wrestling phenomenon of the past.

Randy ‘The Ram’ Robinson is a relic from the wrestling boom years, trying to find his way in a world where wrestling is no longer the cultural force it once was, but is also full of new, young blood, athletic in ways the likes of Randy never were and more appealing to a new audience. We know ‘The Ram’ was a big star—possibly the biggest wrestling star—of the eighties in the universe of the film, and we know this right from the beginning as Aronofsky helpfully makes his opening credits a collage of wrestling event posters and magazine covers from between 1986 and 1989, all featuring Randy alongside such taglines as ‘The Ram goes for the gold,’ ‘The Ram has become the people’s choice’ and ‘Randy “The Ram” Robinson: Wrestler Of The Year!” In the fictional world of The Wrestler, Randy occupied the spot a certain Hulk Hogan did in reality: a true charismatic star with mass appeal and mass success.

Cue the caption: “20 years later.” Randy is sat hunched on a chair in what looks to be an Early Years classroom, his hunched, spent posture at odds with the toy dumper truck on the floor and the colourful, messy drawings on the wall. A figure we presume to be a fan comes into the room, casual in a hockey shirt and jeans. But no, he is the promoter. He hands Randy his pay packet, which is considerably smaller than he expected. “Sorry, I was sure the gate would be bigger,” comes the response. “But don’t forget, two months, Rahway. Legends signing. I need you man.” In the space of a couple of minutes, Aronofsky has masterfully shown us the heights Randy had climbed and how far he has fallen since, picking up shitty pay and appearing at legends shows, confirming that he is now a washed-up has-been.

This is confirmed by the relatively young fan who asks Randy to sign something for him, only to announce the first match he ever saw live was Randy vs. the (poorly named, wrestling fans) Davey Diamond in 1985 at The Spectrum. As Randy pulls his case away across the dismantling gymnasium, the gulf between what is and what has been couldn’t be clearer. Hell, Aronofsky hammers the point home by having the song on Randy’s car radio as he drives away be “You Don’t Know What You Got Til It’s Gone!”

Does Randy know he is a relic? He obviously understands that his position has fallen dramatically from his lofty main event days. No longer the major arenas for him, as we have seen, he finds himself reduced back to the independents, with shows held in High School gymnasiums, in front of a couple of hundred fans (if lucky) instead of the many thousands of fans that would populate a major promotion’s arena shows. As he comes back from that opening show to his mobile home, he finds the lock changed and the landlord not responding. Rent’s overdue again, Ram. As he hunkers down in his car for the night, scooping up the soul of the wine, he spots through a window a wall in mobile home absolutely covered in cut-outs of himself in his heyday. The fact that he felt the need to make this wall is indicative in itself. The fact that he sees it taunting him

Why continue with the charade? True, you could continue out of a love of for your chosen profession, and while I believe Randy does love wrestling, I believe he loves mass adulation and money more. He’s not getting any younger either. The human body, as the history of the physical wrecks wrestling has left behind can attest to, can only withstand so much before it waves the white flag. So why bother? Why not be grateful for the good times and ply another trade? As we shall see, its not a matter of choice for Randy. He honestly feels he cannot do anything else. He is not wired for the ‘everyday’ regular life. Hence, he defines himself by the one thing he can do. He is a Wrestler.

The Wrestler as Social Object

If I say I am a writer, what does that really mean? Does that indicate something about me as a person? Do I fit a certain social order? Does my ‘being’ a writer displace my other facets, such as being a father, a son, a friend, even a man? How does one embody a thing to the point they become the thing itself, rather than a human person practising or doing the thing in question?

Am I a person who writes, or am I a writer? And ultimately, does the distinction even really matter?

Jean-Paul Sartre is one person who would argue that it does. In his defining 1943 philosophical tome ‘Being and Nothingness,’ Sartre argues that people deny themselves freedom by defining themselves by their jobs and therefore as objects. I work therefore I am.

To perceive oneself as equal to their social role, as a narrow, rigid social object, is to be in possession of what Sartre calls ‘bad faith.’ By narrowing their belief in what it is they are, reducing themselves to a singular object, people risk denying themselves the freedom to be all the other things they wish to be, experience other ideas, become other people. One small door opens to a tight fit of a room and a legion of doors slam shut behind you. Freedom, then, is the power to negate objectification, to allow yourself the potential to access all of your possible selves.

For Randy, freedom is not even a consideration. Easier to objectify yourself, to live the dream even when the facts deny the dream even exists anymore. While not lording it up, the respect and camaraderie of the (younger) locker room is something Randy seems to really appreciate, maybe because it’s something he really understands, or it’s something he doesn’t really have to think about. It’s natural now. He is encouraging to young Tommy Rotten (it’s not altogether clear whether he is being sincere but he seems glad of the contact anyway). He slaps hands and backs. He cracks a joke. He knows exactly where he stands in this world, even if it is no longer where he stood.

In its way, wrestling should be a form of negation in and of itself. It should be impossible to call oneself a wrestler in the objectified sense. The men and women we see on the screen are not real in the literal sense: they are characters, gimmicks, a public presentation. Of course, the world we see in the arena or on the screen is also not literal. While taking nothing away from the physical abilities and risks taken by wrestlers (you know by now I’m a big fan), the results of matches are of course pre-determined and storylines determined by the booker (head matchmaker) or booking team. Surely to call oneself a wrestler is to negate the possibility that you could genuinely believe you were the character in the arena, rather than the person behind the character?

Aronofsky is very careful to show the inner workings of the wrestling locker room with respect. He does not dramatize or exaggerate, rather instead giving us an accurate feel for the backstage wrestling environment. He uses a vaguely cinema verité technique, not running around with Steadicams but giving the film an unsentimental, unpolished, direct feel, often following Randy around from behind. No flashy edits. Scenes play out as long as they need to, but the cuts between the scenes themselves are fast. The end result is the effect of watching a documentary even when we know it is not so.

The film compliments this by not shying away from the ‘real’ world of wrestling. We see the booker call out the order of the evening’s matches and naming who will wrestle who. We see opponents working out the structure of their match, what type of match they will have, what ‘spots’ they can put in and how it will end. We see Randy taping a blade to his wrist so he is able to ‘blade’ his own forehead during his match for drama-enhancing blood loss (a real-life practice). We see the shitty payouts, the backstage medical staff stitching and gluing cuts back together and, in the case of a very violent hardcore match, Randy finds himself involved with, pulling staples and glass out of flesh.

Which raises the question: how can Randy hold onto his “bad faith” of being a wrestler, a hero, when he knows the truth behind the curtain? Well, maybe for Randy the illusion is easier to live with than the reality, a statement that could equally apply to his relationship with the ‘real’ world. It is easier to pretend you’re a star, a hero, a somebody, when you’re just about hovering above rock bottom by mere millimeters.

Randy tells his friend and love interest Cassidy about an injury he suffered years before. She asks if it still hurts. “It hurts when I breathe,” he says, “but when you hear the roar of the crowd, you just pull through.” Cassidy laughs, the idea that affection would be worth such suffering leading to her to mock Randy gently for his almost messianic idea of himself. “He was pierced for our transgressions, he was crushed for our iniquities. The punishment that brought us peace was upon him, and by his wounds we were healed.”

For Randy, such negation is wishful thinking at best. It is not the ability to identify another life, one that would make him happy, that is the problem. No, the problem is his inability to bring such a life to fruition.

Dreams of Deli Counters and Intimate Connections

What is an everyday life for most people? The very idea is ridiculous, even as I type. However, there is still a common social thread that a lot of people can relate to in one way or another: the mundane routine of Monday-Friday work, marriage, children, summer holidays, sports at the weekend, mortgage payments. From here springs the myth, true or false, of the suffocating suburbs. But for a lot of people, not only is this something to aspire to but is almost holy grail-like its appeal.

But what if you’re unable to play by the rules that society deems necessary to obtain this life? Not in a conscious, rebellious, ‘I reject your society of conformity’ kind of way, but literally a sheer inability to function in a way society deems acceptable, however much you might try. Welcome to Randy’s world.

It’s clear Randy cannot function in ‘standard’ society. In fact, he seems to lack any sense of worldliness, not in an exotic way, but in a basic, understanding of the world kind of way. Hell, when he goes clothes shopping for his estranged daughter with Cassidy, he tells her that he thinks his daughter might be lesbian—might that make a difference to the clothes she wears? Of course—based on personal taste alone, not her sexuality. We know this of course, but Randy doesn’t. It’s not even from any kind of homophobia. He genuinely doesn’t know if being a lesbian affects a lady’s sartorial tastes. How can one hope to engage with the world if you can’t decipher its codes? If you can’t even engage with your own daughter.

Our very own Andrew Grevas, in his wonderful article on The Wrestler, pointed out how many wrestlers have had strained relationships with their families and their children. Think about it; there are many wrestlers who have or still are away from home for over 300 days of the year, what with Pay-Per-Views, weekly TV shows, and the intense ‘house show’ schedule, especially in the WWE which is notorious for its grueling wrestler workload. So by virtue of the sheer amount of time a wrestler spends away from home, there is already an instant disconnect from their family.

You can add to that the extra-curricular, recreational activities that crop up on the road to stave off the boredom of the grind and perhaps even homesickness. When the party only really ends when you’re in the ring or when you finally collapse, where do you fit your family in? And after years of strained relationships, once the party’s finally over you might find yourself alone, your money pissed away and your body failing, a painkiller addiction the only thing to cling to (Randy certainly knows about this; he promises to hook up the strip club’s bouncer with his connection, who seems to have a wide range of painkillers at his disposal alongside bodybuilding ‘supplements’).

It is Randy’s heart attack that forces him to reassess his life. He has been estranged from his family for many years. As such, his daughter Stephanie, now at college age, is less than enthused to see him.

But Randy doesn’t take this as the end of the matter and its to his credit that he perseveres. He knows he’s done wrong by his daughter in the past and his recent revelation of mortality drives him to reconnect. As he tells Stephanie, in a moment of emotionally devastating vulnerability, “I’m the one who was supposed to take care of everything. I’m the one who was supposed to make everything okay for everybody. But it just didn’t work out like that. And I left. I left you. You never did anything wrong. You know? I used to try to forget about you. I used to try to pretend that you didn’t exist. But I can’t. You’re my girl. You’re my little girl. And now I’m an old, broken-down piece of meat. And I’m alone. And I deserve to be all alone. I just don’t want you to hate me.”

It’s clear that Randy, at heart, is a man who longs for intimate connection. Whether wrestling distracted him from this or gave him a way to escape the emotionally bruising work this can involve is open to debate. But the fact that Randy is self-aware enough to know where he went wrong then and what he wants now, and to take responsibility for this, suggests a person capable of growth.

That’s half the battle.

The other half depends on having the emotional strength to feed and sustain the growth.

To push yourself to become more than you are or to have more than you do is a tough, tough thing to do.

To do so without the social skills or coping mechanisms needed for such an intense endeavour is doubly tough.

Enter stage-left Cassidy.

A Man, A Woman and The Aging Process

And yet—could Randy have found a way to fit in? While he is less than enamoured to have to be working the deli counter at the supermarket during his retirement, he quickly warms up to and actually seems to enjoy engaging with the baffled customers, charming and entertaining them in equal measure.

It’s the performance factor, of course. Wrestling has often been described as having carny origins and in Randy’s joyful performance you could imagine behind a stall at the local fair, playing a confidence trick on the visitors into spending on his game. A lot of wrestlers, those with the real gift of the gab, would probably make great salespeople. It’s all in the performance.

We can deduce then, that the problem with Randy isn’t one of ability. It strikes me that he could have ridden things out if he could have found an employment outlet for his performance abilities outside of the ring. The problem then must be mental or emotional. It is certainly his inability to handle his emotions that ruins his chances of stability at the deli, however monotonous that stability might have been. Couple this with his inability to understand how the world around him works, even on a basic social level, and you can see how the odds stack against Randy.

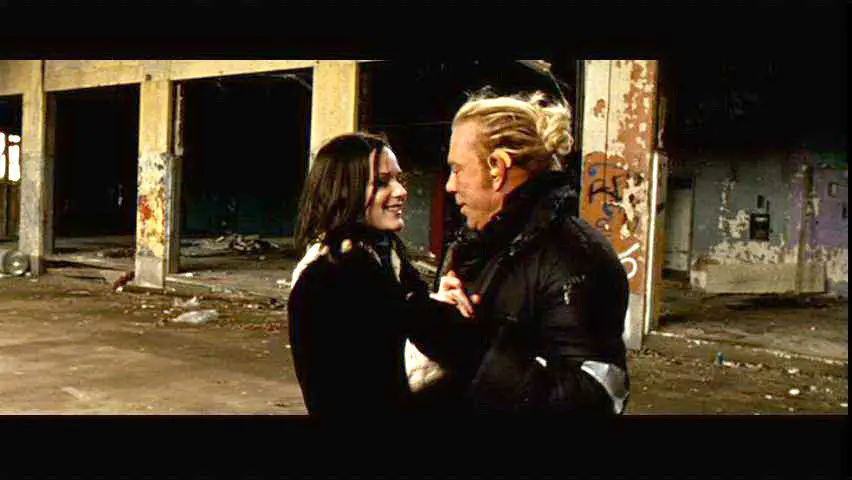

See, Randy wants connection. He wants love. He wants that basic human intimacy that most of us who have it probably take for granted. He thinks he finds it in Cassidy, a stripper who faces a similar existential conflict to Randy with time.

Whereas time takes its toll on a wrestler’s physicality (and also popularity, it can be said), Cassidy finds herself an object of ridicule to young men who objectify these women (and probably most other women too) by their sexual appeal; something they tie in with ideas of youth or youthfulness. What a rotten, narrow box for women to live in; having to live up to a man’s narrow ideal of feminine sexuality, one in which women are discarded as being worthless once the aging process supposedly strips these women of their beauty. It’s no wonder Cassidy looks so drained, exhausted and disillusioned. She is only doing the job to save up enough money for her and her son to be able to move away to a better life. Yet scrutiny, derision and ignorance are all she receives in return.

In his own way, Randy can relate. The ageing process has affected him too, impacting his ability to wrestle to the standard he used to. Wrestling also suffers from it’s own age-popularity relationship, where wrestlers who outstay their welcome are criticised and told to hang the boots by the fans (these usually being fans that worshipped these wrestlers only a few years previously. Wrestling can be a fickle business).

Maybe it is this that subconsciously draws Randy and Cassidy together. As Aronfsky commented:

“The similarities between a stripper and a wrestler which first of all the truth of the matter is that when wrestlers are done—real wrestlers are done with their matches—they usually take their gate and go to the strip club. So that’s probably where the idea started, but then the more we thought about it—an aging stripper and an aging wrestler have a lot of similarities, you know? They’re both onstage using their bodies and they both have stage names. They both create a fantasy for the audience. They’re both endangered by time.”

There is a clear attraction between the two, Cassidy even going so far as helping Randy to choose a present for Randy’s estranged daughter. However, when Randy crosses the line and makes a pass at her, Cassidy resists. It’s a matter of dignity and I believe it is a matter of past experience. She has a rule: no going out with the customers. From the point of view of dignity, perhaps she doesn’t want to be perceived by the other dancers as working a customer for extra money. Understandable, but should that stand in the way if there is genuine attraction and even love there? She would not be working Randy, but sometimes we all let what we fear others will think of us affect our choices.

We can also read between the lines. Cassidy is a single mother, which suggests things possibly didn’t go well with the father. Was she in an abusive relationship and does this emotionally prevent her from connecting with someone else in case it happens again? Were they previously a customer? We are not given enough information to reach a definite conclusion but it seems likely.

Cassidy’s polite but blunt rejection of Randy is understandable but imperfect. It shows her own social inadequacies and her own anxieties. But Randy’s response is much more imperfect and shows his inability to manage his own emotions in such a difficult social dialogue. He nastily insists Cassidy gives him a lap dance if he is just a customer, leading to him being ejected from the club.

On the rebound, perhaps not knowing where else to go or what to do, Randy turns up at a wrestling show to watch and it’s here the seed is planted in his head that this was the only family that loved him, no matter how low down the pecking order he has fallen. He deflects that. He is somewhere that he fits in, a place he understands.

But there’s still his daughter. Right?

Here’s where the wrestler’s proclivity for ‘extra-curricular’ activities provide an unfortunate way to escape responsibility and to release the tension. And as it can in real life, here it all ends in tears.

Following the wrestlers on to a bar, he allows himself to be seduced by a girl who offers him coke, sex, and a bed for the night. He wakes up hungover in the morning to find himself in a fireman fetishist’s paradise and tiptoes back home to sleep it off.

Which he does. Late into the night, way past when he was supposed to meet his daughter at a restaurant, her concession to such a meeting being the first potential steps towards rebuilding their relationship. Not now. Not when she has waited two hours without even a phone call. “You know what?” Stephanie tells Randy. “I don’t care. I don’t hate you. I don’t love you. I don’t even like you. And I was stupid to think that you could change. There is no more fixing this. It’s broke. Permanently. And I’m okay with that. It’s better. I don’t ever want to see you again. Look at me. I don’t want to see you. I don’t want to hear you. I am done. Do you understand? Done.” And then she slams the door in Randy’s face, figuratively and literally.

It’s heart-breaking, partially because Randy genuinely wanted to rebuild his relationship with Stephanie. He loves her and was not just paying lip service to a reconciliation. But what makes it doubly sad is the fact that he squandered his chance with his daughter on—what? Another opportunity to better his life? Cassidy? No, it was a trivial, pointless event that occurred instead. Beer, coke and a cheap lay. Something he could have got any old night. And for this small, ordinary experience, he missed out on something greater with Stephanie. Even sadder, it was not out of selfishness in and of itself but an impulsive reaction to Cassidy’s rejection. He couldn’t control his emotions but at the cost of his daughter.

This understandably puts Randy in a black mood, silently seething at pedantic, moody customers at the deli whereas before you could believe Randy would overcome them with his charm and charisma.

A customer recognises him as ‘The Ram,’ and the gap between where he was stood tall and where he has fallen to is vast and no longer possible to ignore. Randy slices his hand open on a meat cutter in a literal act of self-destruction and quits his job in a hail of swears and boxes spilling to the floor.

My heart breaks for Randy. Yes, he could have reflected, made a mature choice to move on, find love elsewhere. But for some people, it really isn’t that simple. As the doctor famously said about Spike Milligan, Randy was born without layers of skin. He bluffs and he deflects, but he’s hurting. Bad. No-one’s taught him coping strategies or techniques. He might never have been through therapy, possibly would have dismissed it even as something weak. My heart breaks because he’s a man who needs help and he doesn’t know where to go to find it. And sometimes there’s only one place to go from there.

Down.

Randy’s Last Stand (From the Final Ring Post)

Earlier in the film, Randy had agreed to a rematch at a fan convention against ‘The Ayatollah,’ his great nemesis of the eighties. Playing on the real life taste for nostalgia, the match is destined to make everyone involved a fair amount for one night’s work. But after his heart attack, Randy pulled out of the match. Now with his daughter gone again, his rejection by Cassidy and his job thrown away, he feels he has only one option: the show must go on.

To Randy it makes sense. The ring and the locker room are the only places he has ever understood, the only places he felt affection. He forgets that he was allowed to drop to the doldrums as soon as he wasn’t drawing audiences anymore; it doesn’t fit his narrative. And his narrative now is to find a place where he is of worth.

Is it a suicide mission? I don’t believe Randy really wants to die. He knows how severe his heart condition is. He knows that he could likely die in the ring if his heart can’t stand the punishment. Whilst he doesn’t want to die, the difference is he doesn’t care either way. If it happens, it happens. But it will happen, he thinks, on his terms, doing the only thing that appreciated him, in front of the only people who he feels ever appreciated him.

He has neglected one thing. Cassidy. She realises her feelings for Randy and visits him just as he is about to leave for the big show. Could she make the difference? Could she stop Randy from going to his certain fate?

Unfortunately, she does not yield completely at first to the convictions of her heart. She admits that Randy is not just another customer but at the same time she has a line she can’t cross. Randy pretty much blows her off and tells her he’s off to a match. Here is the point of no return. If Cassidy had just given into her feelings, crossed her own line, would Randy have stayed with her? Would he have cancelled the match? I think he would. But he hears another compromised reason, however understandable, as to why it’s not to be and it functions as the full stop on the sentence for him. From here there is no turning back.

So when Cassidy follows Randy to the show and declares “I’m here. I’m really here,” you know how much its taken for Cassidy to be this honest, open and vulnerable. So you can appreciate the pain for all involved when Randy says “Listen. I know what I’m doing. And, you know, the only place I get hurt is out there. The world don’t give a shit about me. You hear them? This is where I belong.”

Randy no longer believes in any other possibilities, even when they are real and in the flesh before him. His mind has locked the door on any hope from entering. Better to burn out than to fade away? Randy has made his choice on the matter. Better, he feels, to die a somebody than die alone and empty.

When Randy enters the ring and tells the crowd, who give him a great ovation, “You people here are the ones who are worth bringing it for, because you’re my family. I love all of you. Thank you so much!,” you know that he believes it. You also get the feeling of watching someone deliver their own eulogy. And as the match progresses and every knock and bump seems to impact his heart more and more, your own heart sinks to watch the sacrifice.

And let’s be clear; it is Randy’s choice, this sacrifice. The Ayatollah sees the pain Randy is in and gives him every opportunity to finish the match, dropping character to urge “let’s take it home Ram!”

Randy has other ideas. Like The Wild Bunch, going out in a hail of bullets to have one last ride in their glory days, Randy goes up to the top rope to signal for his famous finishing move, the ‘Ram Jam’ elbow drop. As he soaks up the cheers and adulation from the audience, we know Randy will carry this with him always, to the grave or otherwise. This is where the world makes sense. This is the feeling he couldn’t carry into his everyday life, no matter the opportunities he had . This feeling, this adoration, this is how Randy wanted his life to feel.

As he leaps from the rope, it feels like watching someone leap from a ten-story building. The camera remains static on the ringpost, allowing for the ambiguity of whether Randy does die or not. We hear the slam to the canvas, we hear the crowd cheer, but we do not know. But that static camera, like all the life has been sucked out of the ring, tells me all I need to know. Life, like wrestling, is sometimes a rotten game.

Better to burn out than fade away? Ultimately, for me, no. I believe in taking joy from life, no matter how small or trivial. It’s this that keeps me going. But others aren’t as fortunate. Others will take that leap from the top turnbuckle.

Stay safe.