Picture the scene: rioters have taken to the streets to express their frustration, their dissent, their civil disobedience. In retaliation, the police form a blockade, attempting to kettle in and contain the threat. They are armed with batons and tear gas and try to force submission with water cannons. In the aftermath, the burnt-out shells of buildings, cars, and rubbish bins stand like monuments to a desolate stalemate. Those who lived here will still live here, now having to pick up the pieces of their lives from the fragments of the debris all around them. The authorities will still sleep soundly, brutalised perhaps, but still comfortable in their comparatively luxurious homes and disposable incomes. Voices have been heard, but at what cost?

What year is this, and where? Paris in 1968? Brixton and Toxteth in 1981? London and Manchester in 2011?

Well, it is Paris, but the year is 1995. Boredom, poverty, failed social engineering, and a glut of police bavures (blunders or accidents) under the stifling heat of the summer sun has seen violent tempers rise with the temperature. These tempers, to be sure, are about to explode.

You can attempt to internalise anger, but more often than not this will fail. Sometimes this rage has a direction, sometimes not. But rage will always need an outlet, and if you don’t provide it with one, it will force the issue.

This is La Haine.

Mortal Slipups

Paris has a long history of civil disobedience, from the aforementioned student riots of 1968, to the French Revolution and the Paris Commune, to the riots of November 2005 that took place in the banlieues (suburban estates) that La Haine so unflinchingly depicts.

Director/writer Mathieu Kassovitz was well-versed in the art of dissent. He was known to have taken place in protests, believing in the improvement of the conditions of life for the disadvantaged, such as would be suggested by the values of the Republic—liberty, equality, fraternity.

He was also keenly aware of the police’s reputation for accidental deaths. As Ginette Vincendeau wrote in 2012, “more than three hundred mortal ‘slipups’ have been recorded since 1981—common enough to have become a topic for comic films.” It was clear then that, far from being accessible, police brutality had become accepted as an everyday fact of French life.

It was one such incident of brutality that inspired Kassovitz to write the script for La Haine the very same day. On April 6, 1993, Makome M’Bowole was accidentally shot to death by Inspector Pascal Compain, who declared he had been trying to intimidate a confession from M’Bowole by pointing his gun at his head and dragging the confession out by fear. Compain had thought the gun had been discharged when it had not been, leading to M’Bowole being shot through the head at point-blank range.

If the incompetence of not checking the gun was bad enough, the willingness to intimidate a suspect into confessing is even worse and says so much about the attitude of those in authority towards those without. The people who still advocate the arming of British police should take note. Kassovitz would later ask “how a guy could get up in the morning and die the same evening in this way.”

There was a further case, the death of Malik Oussekine in 1986, that also inspired Kassovitz. Oussekine was only 22 years old when he was brutally beaten by a motorcycle police patrol that had been ordered, after mass demonstrations against university reforms, to round up supposed “thugs” who had dispersed to the Latin Quarter of Paris. Oussekine had just left a jazz club and had not been involved in the demonstration. He was actually in the company of a member of the Ministry of Finance when he was attacked, dying before the ambulances could arrive.

Kassovitz used the tragic death of Oussekine as his starting point for his script, having fictional news footage, complete with an anti-authoritarian dub reggae soundtrack, depict rioting in a banlieue, in which one of their residents, a young man named Abdel Ichacha (Abdel Ahmed Ghili), is in critical condition in hospital as a result of a beating by the police. The resulting rioting is all the more terrifying for its depiction in a documentary, almost CCTV-like fashion, etched in black-and-white and as authentic-looking as can be. In the middle of the violence, a police station is assaulted and a gun stolen from a riot policeman. This will have deathly consequences by the end of the film.

Streets In The Sky

The banlieue is perhaps most comparable to the council estates of England and the housing projects of America. As readers familiar with such places may possibly attest to, the poorest and most vulnerable members of society are often pushed out into such areas, usually by being priced out of “quality” housing and/or gentrification of an area to bring in a more “desirable” type of resident, usually a young professional with money to spend (as is the case in Salford off the back of both the BBC and ITV relocating to Media City down at Salford Quays).

Furthermore, such estates tend to be quite insular, based on their design and layout, enclosing people in on themselves and each other to the point of claustrophobia. In tower blocks, the French architect Le Corbusier’s idea of “streets in the sky,” people live on top and under each other with walls as thin as tracing paper, letting every little sound seep into their personal space. It’s no wonder that under such circumstances tensions spill into aggression.

Ginette Vincendeau argues that, in France at least, the banlieues “concentrate social problems: run-down housing, a high concentration of young people from immigrant backgrounds, drugs, and rampant unemployment. Their social deprivation and cultural alienation are echoed in their topographical isolation from the city center.” Monmartre, this is not. And yet why shouldn’t it be? Why force the more vulnerable and less financially able into such Brutalist surroundings? Such statements, of course, reopen long-held arguments regarding the need for quality but low-cost housing, the correlation between earnings and quality of housing you can afford, and the relationship between types of aesthetic in housing and class. All arguments, sadly, that continue on with no end in sight.

This is the world the characters of La Haine inhabit, hemmed in by dominating tower blocks and in conflict with their own boredom, as well with as the authorities. And yet as we shall see, in the face of such adversity, the shared experience of their place in life and their sense of “us against them” enables them to transcend barriers they might not have been able to otherwise.

Empty Space and Gangsta Rap

The three main protagonists in the film, banlieue teenagers all, have a difference in common: they are all of different ethnicities. Vinz (Vincent Cassel) is Jewish, Hubert (Hubert Kounde) is Afro-French, and Saïd (Saïd Taghmaoui) is a North African Muslim. This is quite representative of the fact that new immigrants with little in the way of funds will inevitably be pushed into the banlieues, which then feeds into a kind of segregation from the home-born communities of their adopted country. This failure to integrate in turn breeds a kind of tension and resentment, often double-sided, which in La Haine expresses itself in violent conflict between the police and the residents of the banlieue.

However, in La Haine, by virtue of the shared experience of being swept into the corner, as it were, a camaraderie between these sons of immigrants has emerged, represented by the tight bond between Vinz, Saïd, and Hubert. They can each relate to the feeling of being unwanted by their adopted country (if the actions of an authority confirm the feeling of the country it represents, anyway.) They might insult each other’s ethnicities (the adjective ‘bogus’ is applied to racial slurs and words like “kike” and “Arab”), but there are strong bonds between them all that transcend race.

It’s a bond forged in empty time. There is very little to fill up the time. In the early parts of the film, Vinz, Hubert, and Saïd are seen to be hanging around on bits of apparatus around the estate, winding each other up about Saïd’s supposed sexual encounters, visiting drug-buying customers, or listening to a younger member of the estate’s seemingly endless story about a Candid Camera moment gone wrong. Vinz sums it up by not recognising the punchline of the story. “Then what happened?” he asks. Nothing, that’s the end of the story. But young people want more, expect more than empty time. A half-arsed punchline to their lives won’t do. A piece of graffiti behind Hubert reads, “We’re the future.” It’s what the teens on the banlieue demand, but we as the audience aren’t convinced for a second that they believe that.

Still, in such draining surroundings, culture can still flourish, from the way people dress to the way people talk. In 1995, hip-hop was at the forefront of youth culture, less predominantly than today perhaps, but certainly a major artistic and commercial force. More pertinently to this film, it was more of rebellious art—against racists, the authorities, and a system skewed in favour of the rich rather than the poor in the projects. Certainly, a lot of gangsta rap was in favour of getting that green, but only because they understandably felt that they were being prevented from getting it by the racism and classicism of the authorities.

It’s understandable then, although hip-hop was black American art discussing black American troubles, how the message translated to poor, angry, immigrant teens in the banlieues looking for a rallying cry. Hip-hop culture is all over La Haine. Tracksuits and sportswear are the predominant clothing of choice for the teens. Ice Cube graffiti adorns the estate. Saïd spraypaints the phrase “F–k the police” on the back of a police van, a nod to the N.W.A. track of the same name. A group of breakdancers practice in the lobby of one of the towers. A DJ in one of the towers sets up his twin decks and a speaker in his window and blasts an awesome mix of KRS-One’s “The Sound of The Police” scratched into “Nique La Police” and “Je Ne Regrette Rien.” Vinz rolls a joint whilst he, Hubert, and Saïd drop into the chorus from Naughty By Nature’s “O.P.P.”

The importance of this is clear. It gave poor French teenagers an identity and a way of talking and looking that was more in line with their Brutalist, survivalist everyday life than the French homegrown culture of their parent’s generation. A classic subcultural story, perhaps, but one which here was adopted by the teens of the banlieue as part of their very essence.

Hip-hop gave them a way of being. But it did not give them a way out.

Saïd

Of the three main protagonists, Saïd is perhaps the least substantial. Often he is used as comic relief, a balance to the tension of the plot and of his friends. His eye-bulging shock every time someone mentions his sister becomes a very funny running joke, even if it does tip into misogyny. His rising panic when Vinz butchers his hair during a simple trim becomes more hysterical the closer Saïd gets to hysteria, which is complemented beautifully by Vinz’s own barely concealed worry under his assertions that everything is OK and it’s “just cold in this room.”

Even then, though, there is more to Saïd than just layering in the laughs. He is clearly excited when he realises Vinz has the missing policeman’s gun and tells him, “You’re the big man.” Yet, when faced with the actual possibility of Vinz firing said gun, he freaks. “You’re on your own,” he tells his friend, although that doesn’t last for long. Nothing is real until it becomes real for you, and for Saïd, he quickly discovers the difference between the fantasy and the reality of being a gunman.

This doesn’t stop Saïd entering into other dangerous areas, though. Everyone has their way of surviving in the banlieue, and for Saïd, it’s drug dealing that helps put money in his pocket. Occasionally, this puts him in a position to see life from the point of view of his customers. When he visits ‘Walmart’ (Edouard Montoute) to collect his money, Walmart replies that he can’t pay because his car was burned in the previous night’s riot. “I lost ten grand! I can’t work now.” When Vinz chuckles that “it’s just a car,” Walmart doesn’t see the funny side. “That’s what you say! You don’t realise it’s all I got.” Although this is clearly an awful situation to be in, Hubert later describes Walmart as a ‘Fence,’ suggesting to me that he might easily be able to “acquire” a car later on.

Some of Saïd’s other customers are not so lost, though. Visiting central Paris to collect money from “Snoopy” (Francois Levantal), he arrives with Saïd and Hubert to discover a clearly well-off man in his spacious apartment, eccentric to put it mildly, dancing around in nothing but a towel or a sarong and challenging Saïd to a kung-fu play fight. Which is all well and good until Vinz notices Snoopy’s gun and pulls out his own to show off. Snoopy challenges Vinz to a game of Russian roulette and slaps him repeatedly when he won’t take part.

Saïd is forced to leave without his money, and Vinz asks him later how much Snoopy owed him. When he answers $100, Vinz exclaims, “All that sh-t for a lousy $100!” “It’s the principle,” comes the sullen reply. Sometimes, when you have nothing, principles are the only thing to hang on to. Perhaps this why Saïd is the only one of his friends left alive by the end of the film.

Vinz

Vinz is a strange mix of bravado and vulnerability. He is keenly aware of the contempt in which the people of the banlieue are held by the authorities and believes that violent protest is the only way to properly revolt. “If Abdel dies,” he says, referring to his hospitalised friend, “I hit back. I’ll whack a pig. So they know we don’t turn the other cheek now.” For Vinz, the police get away with their brutality because the victims let them do so. Now armed with a policeman’s gun, he is ready to strike back.

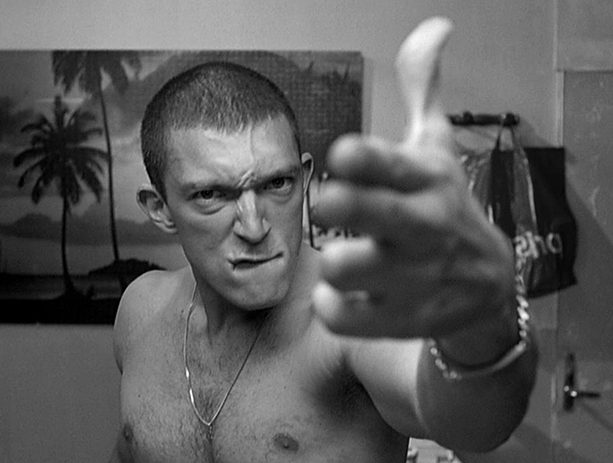

This is not the only reason, though, for Vinz’s attitude to violence. On the one hand, he romanticises gun culture. This could be seen as the influence of the hip-hop culture that permeates the banlieue, where gun violence and anti-police sentiments mix easily. There is also possibly the influence of cinema, lending a sense of detachment and romance to Vinz’s idea of gun violence. He poses in the mirror reprising the famous “You talkin’ to me?” scene from Taxi Driver, the idea of Robert De Niro’s avenging angel at the forefront of Vinz’s mind. Later, we actually see him in a cinema, pointing his fingers like a gun at the screen. When he tells Hubert and Saïd at the start of the film about the previous night’s rioting, he does so with all the giddy excitement of a child describing his first football match.

Then again, there is also a vulnerability to Vinz’s attitude to guns, a need for acceptance from his peers. He talks enviously of his peers’ time spent in jail, time he has yet to spend. When Hubert asks Vinz if he is going to kill a cop, Vinz answers that it’s “the best way to get respect.” Though he will also add that it will even the score, it betrays a certain predominant need in Vinz to get the respect and admiration of his peers. In a culture that venerates gun violence and hating police, shooting police, in Vinz’s mind, is the best way to quickly gain such respect.

He soon changes his mind when he sees the consequences of gun violence firsthand. Vinz has hooked up with some friends at a boxing fight they are watching. As they move on to a club, the bouncer refuses them entry. One of the party loses his temper, claiming this particular bouncer always denies them entry, and shoots the bouncer dead in the club’s doorway, as Vinz, his shock emphasised by his face being superimposed over the shooting, can only watch in mute horror. That he quickly leaves the party and finds his way back to Hubert and Saïd at the train station is telling. It’s one thing to daydream gun fantasies, quite another to stare gun violence and death in its cold, stark face.

Later, when confronting a skinhead who was part of a gang of skins racially abusing Saïd and Hubert, he points his gun at the skinhead with the intention of blowing his brains out. As much as Hubert quite rightly hates what the skinhead stands for, he knows if Vinz shoots the guy, the doors to Vinz’s future will close, not open. Trying a spot of reverse psychology, Hubert rants at Vinz, telling him all the reasons he should kill such a despicable person. Without a conflicting voice to rebel against, Vinz is forced to confront the situation and, perhaps while reflecting on the shooting earlier in the night, comes to the conclusion he cannot do it. He cannot take a life. The reality of such an act is almost too much to bear, and finally, the concept of life and death becomes concrete, not abstract. The need to belong cannot override the desire to do the right thing, ultimately.

When the gang of three finally arrive back at the banlieue, Vinz hands the gun over to Hubert, knowing that Hubert will do the right thing and dispose of it. It’s a gesture that reconciles the two, and for a moment the future seems hopeful, as if the three have shared a moment of enlightenment.

As we shall see, though, enlightenment can only take you so far. Especially in the face of an assault.

Hubert

Hubert fascinates me. It is clear that he has a more experienced past than the other two. He has been in the navy, and it is referred to that he used to be a pickpocket. He also has a brother called Max who is in jail.

The film never confirms it, but I suspect Hubert is older than Saïd and Vinz. They look up to him, and it is clear that Hubert is the big brother figure of the group. He constantly admonishes Vinz over the gun, and its Hubert that Saïd turns to and asks to set him up with some women he spies in an art gallery, knowing Hubert has the confidence necessary. Vinz describes a month jail sentence as not being in Hubert’s league, even though Hubert protests that he has never been inside, and anyway, he finds the idea of getting sent down pathetic.

Here is an interesting paradox: Saïd and Vinz look up to Hubert for his more criminal and primal skills but don’t seem to be interested in his desire to turn his back on that life and start anew on the straight-and-narrow. Hubert has seen the aggression and the destruction that occurs on the banlieue and wants to escape it, figuratively and literally.

His first attempt to transcend it all was to open a gym on the estate. As he well knew, he could not stop the aggression of the banlieue, but he could give people somewhere to channel that aggression, develop their bodies in the hope their minds will follow. They might even make a career out of boxing if they get good. A poster on the gym wall suggests that was indeed the way Hubert was going.

But the times they are a-changing, as Hubert knows. The latest riot has seen his gym torched. “Kids want to punch more than bags now,” he concludes sadly as he contemplates the idea of another gym. Here we can see his sense of fight get diluted into resignation.

It’s the sense that things are getting worse than better which is the trigger for the dampening of Hubert’s spirit. “I’m sick of the projects. It’s getting worse,” he bemoans to his mother. “I’m sure Vinz helped torch the gym. He’s going wild, like Max. I have to get out. I have to leave this place.”

His mother, more cynical or perhaps just more worldly-wise, dryly retorts, “If you see a grocery, buy me a lettuce.” She knows Hubert is going nowhere. Yet she still encourages her children in her own way. Her daughter is at the table doing schoolwork, and mother worries how her jailed son is going to get textbooks to study for his high school diploma whilst inside. Hope has not been truly extinguished.

So what is it that keeps Hubert resigned, and in his place? Paradoxically, it’s his friends, the bond which sustains him, helps him feel less alone, that fuels his downfall in the end. Because they’re banlieue kids, they are, shall we say, less than educated in social etiquette. They are not afraid of making themselves known, as is the case at the art-gallery event they gate crash, smashing the art, stealing the drinks and insulting the (admittedly stuffy) patrons and women (who in fairness were not putting up with the boys’ masculine, misogynist aggression).

The gym was Hubert’s last hope, rightly or wrongly, of getting the cash together to leave the banlieue. Without it, he has resigned himself to his hemmed-in existence. He starts to smoke weed again, demonstrated in quite a sensual manner as he is shown rolling up to a smooth soul record. He follows Saïd on his trip to central Paris and, as frustrated as he gets with Vinz’s gun lust, joins them in their wild activities, attempting to steal a car, crashing the gallery, and insulting supposed racists in the metro station. No harm ultimately comes to them, though, through these actions. “Like us in the projects,” Hubert tells Vinz. “So far, so good. But how will we land?”

The authorities provide the answer: back on earth with an almighty smack. Leaving Snoopy’s apartment, Hubert and Saïd are pulled in by police responding to reports of a disturbance. The boys hadn’t known which house was Snoopy’s and so had pressed every buzzer, annoying every other resident in the building. Their lack of etiquette invited the appearance of the police. And yet, they do not deserve when they get in return.

The police are training a new officer and, in a disturbing scene, demonstrate how to best hurt a suspect but stop just in time before you lose control. They discuss and demonstrate this with all the excitement of someone pulling out just before they feel they might ejaculate. Indeed, both Saïd and Hubert are discussed in unflattering sexual terms as they are beaten. It is dehumanising and cruel. The two officers leave the trainee to watch the suspects. He shakes his head at what he has seen but cannot meet Hubert’s gaze, averting his eyes in shame. Here is the police system of the time, indicted in a single lowering of the eyes.

The two are set free, but the damage has been done. Hubert is on the edge of no return; he just doesn’t know it yet. There seems to be a momentary respite when Vinz concedes that he cannot pull the trigger—he is not a gunman, after all. He hands the gun over to Hubert to look after, but it’s too late. The police just happen to be at the train station as they arrive back home and decide to make an example of Vinz, no grounds of suspicion needed. Without provocation, Vinz is put in a headlock and threatened, a gun pressed against his skull. It is clearly meant to intimidate and scare, but the gun accidently fires and Vinz, like Makome M’Bowole before him, is tragically slain, for no other reason than a policeman took a dislike to the look of him and decided to set an example by intimidating him. It’s pathetic and tragic in equal measure, and it is the final straw for Hubert.

He approaches the stunned policeman, spooked and surprised by his own incompetence and laughing nervously, and he pulls the gun that he had spent so long preventing Vinz from firing. Earlier in the film, whilst lecturing Vinz, Hubert had argued that “in school, we learned hate breeds hate.” Then, Hubert was trying to prove to Vinz the futility and self-fulfilling prophecy of hate. Now he is living it. As Hubert and the policeman pull their guns on each other in a standoff, the camera closes in on Saïd, in shock and in despair that this is all unfurling in front of his eyes. A gunshot fires, and the screen snaps to black. We don’t know if Hubert is living, if we can call this existence living, but it seems clear to me the bullet has claimed another victim of and from the banlieue. Here is the pathos of the film: that authority demands our poorest drag themselves up by their bootstraps, yet when they attempt to do so they are still looked at with contempt, leading to violence, often with tragic circumstances. Hate breeds hate, indeed.

Throughout the film, Hubert relays the story of a man falling off the top of a skyscraper. “On his way down past each floor, he kept saying to reassure himself, ‘So far so good…so far so good.’ How you fall doesn’t matter. It’s how you land!” La Haine almost proves the opposite: that you can try to improve your lot, but the authorities will always hold you in contempt. Hate breeds hate. But I don’t believe the film is without hope. That moment before the guns go off at the end of the movie, where the three friends stand united in understanding, goes to show that through connection and understanding, enlightenment can follow. There are no guarantees, and there will be opposition and conflict, but where there is a chance to connect, there is a small slither of hope that things can get better So far, so good.

Was absolutely stunned by this, a brilliant film!!!