Here at 25YL we’re jumping, stomping, and diving into the most iconic and popular video game franchise ever, the Super Mario Bros. series. Each week, we’ll take a unique look at each game in the series, and discuss aspects you may not have considered. This week we look at Super Mario Bros. 3, the last (and unquestionably best) of the NES trilogy.

While the original Super Mario Bros is an absolutely landmark title for the gaming medium, and is still solid fun to this day, there are definitely elements of it that haven’t aged well, and it’s all because of Super Mario Bros 3, the first real sequel to the original. As we have covered before, the American Super Mario Bros 2 was aped from another Japanese game that had nothing to do with the mustachioed plumber, and the Japanese Super Mario Bros 2 was more of an expansion pack for the first game that made everything comically unfair. One can only imagine the pressure that director Takashi Tezuka and the game’s creative team were under. How do you follow up a game that wasn’t just popular, but a certified worldwide phenomenon?

The answer is by throwing literally everything at the wall and making it all stick. This game introduced an almost endless list of things that have been series staples ever since, and when given a second look considering the context the game was made in, it’s rather jarring just how flat out weird this sequel is. But that weirdness is what makes the game great, and looking back on it from the modern day, it’s clear that this is one of the greatest video game sequels ever made for a variety of reasons.

It’s Not Real, Again

As a kid playing this game, you kind of take the game’s strangeness in stride. I didn’t question the red curtains that lift to reveal the game’s title screen and Mario and Luigi doing shenanigans with the game’s various enemies and power ups, a few of which we hadn’t seen before like the now iconic Super Leaf. I didn’t question why Mario was able to drop down behind certain parts of the scenery. And most of all, I didn’t question why I was somehow winning the game even though my controller wasn’t plugged in (my Dad knew I would get frustrated as a wee lad because of how terrible I was, and would “play the game for me” while I remained blissfully unaware that I wasn’t actually playing).

For some reason, some crazy bastard at Nintendo decided, like the American version of 2, none of the events in the game were real. Instead, everything was some kind of play being acted out for an unknown audience (a conceit that would, weirdly enough, crop up again in the simply magnificent Paper Mario and the Thousand Year Door). I don’t know if they were worried about the Mario continuity, and felt that all the crazy new power ups and air ships and everything would clash with the established canon from the first two games. It’s fun to think about though.

Regardless, it helps set the stage, as it were, for just how expansive this sequel would become.

(An) Expansive World(s)

The first game was an entirely linear set of levels and worlds, and the only way to not play every level was to discover the game’s hidden warp zones. So imagine the world’s surprise when they had some choice in what levels they played in this entry. The game introduced an over world map that players could traverse between levels, and simple though it was, it really helped break up the pace. You didn’t need to complete every level, but the game did something that is so common place now that it’s easy to forget what a strange idea it was at the time for the platforming genre.

Completing extra levels led to extra rewards!

I’m not going to say that Super Mario Bros 3 was the first game to ever introduce the idea of extra challenges for extra rewards (especially since Zelda and Metroid were all about exploring and discovering secrets) but it was the one that popularized the idea for the platforming genre. In the original game, you might intentionally play through every level simply for the experience of taking in the nice level design. Here, the developers dangled a carrot in front of your nose, incentivizing the player to play the game to its fullest extent. Completing levels could open the way to item houses, or mini games where you could potentially earn a few 1 ups. They even introduced moving mini levels, such as Hammer Bro fights, among others, further incentivizing the player to play through as many levels as possible.

It’s an idea so simple that it would take a team of creative geniuses to think of it. While gaming was certainly gaining popularity at this point in time, developers still weren’t totally sure what worked and what didn’t and were kind of just seeing what stuck. It’s why there were so many NES sequels to the original Mega Man-Capcom had found a formula that worked, and improved and reiterated upon said formula.

But the game’s expansion of the world goes deeper than just the map system. Now each world had a different theme. The original’s aesthetic pretty much remained the same throughout, with each world just being a harder version of the previous one. In Super Mario Bros 3, players were rewarded for overcoming the end of world challenge with a brand new set of levels in a visually different environment. Classic ideas that still pop up in the Mario franchise include the desert world and water world, but there were some more outlandish ideas like Giant Land, where sizes of enemies and environments would change at the drop of a dime.

Themed worlds and even overworld maps are now standards in the platforming genre. These ideas introduced in this game have influenced not only later entries in the series, but too many other games in all kinds of genres to count. But that’s just the broad framing device for the game. After all, a platformer is only as good as its levels.

Leveling Up to Greatness

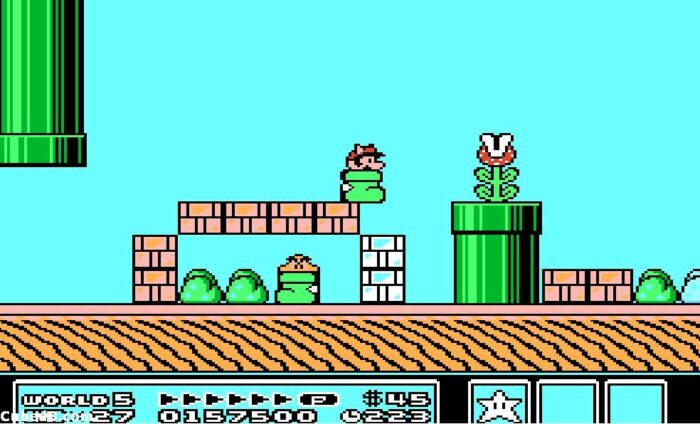

Thankfully, the level design saw similar care go into it. Now, not only could you now go backwards—gasp!—but the game added a startling number of secrets for eager players to find, giving them a reason to use the various power ups introduced in this game. Perhaps the most iconic power up to come from this game is the Super Leaf, which gives Mario a tail and allows him to shoot up in the sky after getting a head start. He could also whip enemies with said tail, which is handy if you want to kick around some Koopa shells.

The developers went all in with the game’s level designs. Each world had a theme, and within those worlds, each level typically had some kind of new idea it raised and presented to the player. Sure, running through the desert and dodging enemies and quick sand is tough enough, but there’s a level that asks the player to do it while also dodging an angry sun, adding an extra layer of challenge to the proceedings. Another standout is a mid-way level where Mario spends the entire thing bouncing around in a shoe and using said shoe to traverse terrain that would otherwise be deadly to him.

It gives the game a huge air of unpredictability. Playing through it for the first time, you’re never quite sure what kind of challenge the developers have cooked up for you in the next level. It leads to a feeling of genuine excitement as you step into a new level. But the game wasn’t content to rest on its laurels with its boss monsters, either. A pretty common criticism of the original game is how each boss is just a remixed version of the fight with Bowser. It was repetitive, and extremely easy, and running through same-y looking castles wasn’t all that fun.

Here, the developers instead have Mario take on one of the seven Koopa Kids aboard their airships. This was, to the best of my knowledge, the first incidence of automatic level scrolling in the series. I will admit that auto scrolling levels tend not to really gel well with me, but they do let the developers set up extremely specific challenges for the player. The airships have nice, foreboding music that builds up to the confrontation with the world’s respective Koopa Kid. These are enjoyable, if still pretty easy, fights where you must memorize their movement patterns to succeed, with each one having a different one to pick up on.

It makes the final confrontation with Bowser feel that much more special. Rather than seeing the same villain get his ass whooped a bunch of times (and thereby robbing him of any threat he may have had), the game builds to a final showdown. Sure, it’s not the toughest fight, with the player just having to get him to butt stomp his way into a pool of lava. But it really makes the game feel like a grand adventure instead of a series of repeated challenges. Each world’s final boss is a great palette cleanser from the main game, but everything comes together magnificently to give the game a tremendous sense of pacing. Just as you’re getting bored with the levels, bam, it’s boss time. Then it’s on to discover a brand new world with a whole new theme and look.

In other words, this is a classic example, and should probably be taught in classes, about game design (it probably is, but I never took such a class). It uses its level and world variety, as well as rewards for extra challenges beaten, to make the player keep pushing on in a way that the first game failed at. Not to say the first is a bad game, but you play it for its own sake rather than out of a sense of progression.

Mario Gets a Wardrobe Upgrade

We’ve already touched on the Super Leaf, but the game introduced quite a few new moves for Mario and Luigi to get. In addition to the return of the fan favorite Fire Flower, you could get the Tanooki Suit, which was like the Super Leaf except you could also turn into a statue and become invincible (remember when I said this game is weird?). There was the P wing, an uber-powerful item that gave Mario infinite flight throughout an entire level, extremely useful if a player got really stuck. There were the Warp Whistles, which were always super tough to find, which brought Mario to that most hallowed of platforming halls, the Warp Zone. It was a smart move, since players could now choose when and if they wanted to warp instead of being corralled at predetermined levels like in the first game. Lastly, there was a frog suit added in that made Mario control like he didn’t have a massive dump in his pants underwater.

Going back to the worlds and levels, these power ups are extremely fun to use, meaning that players want to find them. It made each item house feel like an oasis. You never knew what item you would get from a treasure chest, and in an even more brilliant move, an item bank was added so that players could choose when and how they powered up. It meant that players wanted to beat those extra levels just for the chance of getting a Warp Whistle, or a P wing, or even a Super Mushroom, which can always be helpful in a pinch. These items felt like meaningful expansions to the standard Super Mushrooms and Fire Flowers of the first game.

A Pair of Dapper Brothers and a Bunch of Catchy Tunes

The first game’s 1-1 song is the stuff of video game legend. People who don’t know what a video game is probably know the song. People who love video games but hate Mario (for some reason) know the song. It was a simple, catchy-as-hell chip tune that worked its way into the brains of millions of people around the globe. The underground theme is just as iconic, too. The thing is, the first game really had just a few more songs than that. Great, catchy, and iconic songs, but the overall quantity can leave something to be desired.

In this game, different kind of levels all have different kinds of themes. Not only did some classic tracks get updated with cool remixes, but a whole host of brand new and great songs were introduced. Who could possibly forget the upbeat, frantic pace of the Overworld 2 theme? Or how about the imposing Airship theme? Or the theme when you fight against Hammer Bros? This game added a whole litany of music, and every piece was a winner. Hell, each world map even got its own theme song.

It helps that the game is a shining example of 8-bit pixel art. The first game still has a certain nostalgic appeal, but it’s tough to say that it’s truly a good looking game. Sure, it does the job in communicating exactly what you need to know visually (enemies, obstacles, etc.) but the style hasn’t aged terribly well. While 3 has definitely aged, it’s still a really nice looking game, even ignoring nostalgia. Mario and Luigi have a wider range of animations, like them turning on their heels or holding their arms out as they fly through the sky.

The worlds helped really break up the visual design too. Just as the desert world is getting old, with its oranges and browns, suddenly the player is transported to the deep blues of the water world. Later levels in the final world take on a particularly imposing edge with their deep blacks and reds. Fitting since they lead up to Bowser’s castle, and are also pretty tough.

Here at World 8

It’s difficult to describe in words exactly how great of a sequel Super Mario Bros 3 is. I listed off a whole bunch of examples, but you really need to put yourself back in the shoes of people living in a world pre Super Mario Bros 3. Gaming was young. Developers still weren’t sure exactly what was a good idea and what wasn’t. It’s why certain franchises have persevered through the decades since while others have fallen into obscurity. So it’s nothing short of a miracle that the good people at Nintendo made so many huge decisions about the Mario series’ core gameplay and it turned out to be this spectacular.

Because, really, it was just a bunch of people bouncing ideas around. You see it in the sheer, wildly imaginative level design, the goofy power ups, the phenomenal soundtrack, the still-visually-appealing graphics, the expansion of almost every single idea present in the first game. I’ve touched before on how sometimes, the best games are happy accidents, and this is an early, shining example of that. Even ignoring nostalgia, this game holds up. There are certainly parts of it that are dated, but it is still an incredibly fun and well-designed platformer and a platinum standard for what a video game sequel should be.

I can’t even imagine how difficult it must have been to make a game about a pudgy Italian dude with a mustache running to the right this great, but Nintendo did it all those decades ago, and the end result is a bona fide, stone cold classic in every single sense of the word.

I enjoyed this, Collin. Mario 3 is a timeless classic!