Michael Haneke’s 2005 thriller Caché begins with a static image of an affluent house in a seemingly quiet suburb of Paris, leading to one of the most iconic opening scenes of 21st-century cinema. For nearly two and a half minutes life ticks by, the credits appearing one by one until they fill the entire screen. The diegetic sound of the street is briefly interrupted by a man and woman talking off-camera. Protagonists Georges Laurent (Daniel Auteuil) and his wife Anne (Juliette Binoche) leave the house, then re-enter. What is now clear is that from the outset, we have been watching a videotaped recording of the exterior of the house that has been sent through the post to the Laurents that very day. As the couple scrolls through the footage of that morning’s events, seeing the comings and goings of their street and witnessing themselves leaving for work, the mischievous unease of the Haneke brand kicks in.

Fifteen years after its Cannes release and subsequent receiving of the Prix de la mise en scène (Best Director Award), Haneke’s fraught and unsettling masterpiece on individual and collective conscience resonates more than ever. Its story, as seen through the eyes of a prosperous Parisian family who begin receiving videotapes and pictures through the mail, is certainly not shy of its aims. It is an unnerving, 117-minute morality tale that points to the guilt and denial in all of us and how no one individual or nation can ever be entirely innocent. Hitting hard on the metaphor and unrelenting in its capacity to leave its audience feeling more than a little on edge, it is as relevant today as it ever was. As Alin Farhadipour [1] states, “It is […] a film about surveillance with its functions, limitations, and deceptions” and it is also a warning. In 2020, and in light of the major global revelations to the aforementioned, the ever-increasing rise of social media and a culture where anonymity can be used as a springboard for every gripe, score, and confession, it would seem the projection of oneself can be as honest, fabricated, heroic, or as sinister as we choose. Now is as perfect a time as ever for a reappraisal of one of Haneke’s finest moments.

The Springboard Of Anonymity

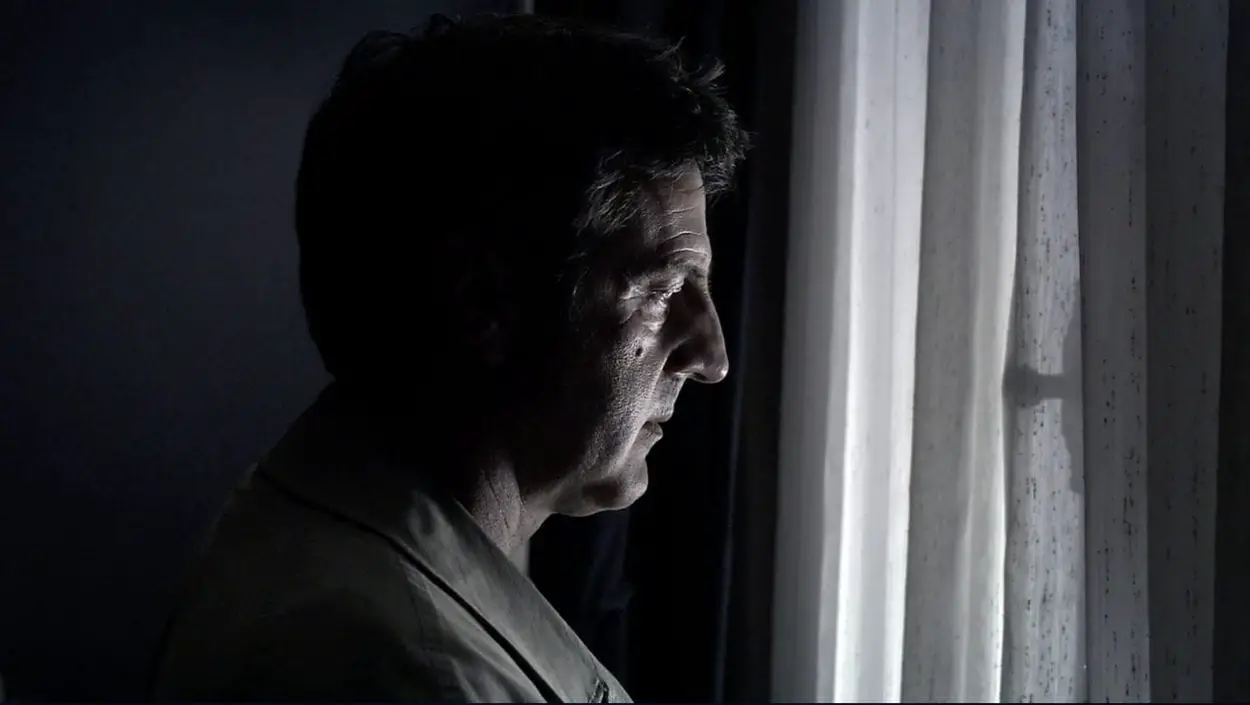

As a title, Caché (Hidden in English) acts as a number of points of study within the film: the hidden camera, the hidden identity of the stalker, and the house and choice of neighbourhood where Georges, Anne, and their young son Pierrot (a sullen-faced, rather moody child, solidly played by actor Lester Makedonsky) live. Then there’s the central intrigue, Georges’ concealing of events from his own past, not just from himself but from his friends and family, especially his wife. Juliette Binoche (playing pitch-perfect here) is patient but firm. Almost frustratingly so. Her attempts to get through to Georges, to give up information he is so obviously concealing, is a first-class lesson in restraint. However, Anne becomes increasingly irritated with Georges’ reluctance to reveal all. On a larger, national scale, there is also the French denial of the Paris Massacre of October 17, 1961, where under the guidance of Maurice Papon, head of the Parisian police, protesters of the Algerian pro-National Liberation Front were beaten to death and in some cases thrown into the Seine to drown. As Guardian columnist Kim Wilsher [2] wrote, “the French government has never officially apologised for the bloody attack–which does not appear in school history books. According to officials, less than a handful of protesters died, while historians say the number of Algerians killed was between 50 and 120.” What we as viewers are witnessing and possibly colluding with here then, on both a personal and national level, is this need to control public perception, to either obfuscate or orchestrate the facts into something more palatable or even to outright deny them altogether.

Theories abound with Caché. Just who is sending the tapes? And those strange, seemingly child-drawn pictures? As the deliveries become more and more frequent and certainly more ominous, and after going to the police with his family’s concerns, Georges decides to investigate for himself. We are introduced to the possibility of four main players here. There is the prime suspect in the figure of Majid (an excellently subdued and washed up Maurice Benichou), a little boy from Georges’ childhood, now only a couple of years older than Georges himself, whom Georges knowingly (even if only as a jealous child) lied about in order to have him removed from the family home. Then there’s Majid’s son (played by Walid Afkir) not named in the film itself, who is angry at the treatment his Father has received from Georges, and Georges own son Pierrot. However, no further justice to the question of the central mystery of this film can be illuminated here. Besides, Haneke has been pretty straight-up with this line of questioning over the years, always noting that his role as filmmaker is only to pose the questions that will hopefully have us asking many more. There’s certainly no time for the tying up of loose ends here, no desire for cathartic conclusion. In Haneke’s world, for better or for worse, it’s just business as usual.

All the way through Caché, Haneke derails our suspicions, intent on playing with us right up until the very last scene in which we witness Majid’s son and Pierrot meeting outside the school. This meeting is an entirely new event for the viewer, and not once has a relationship of any kind been hinted at in the narrative so far; many viewers have actually missed this encounter as the action happens within a bustling, static shot, to the very far left of the frame. Majid’s son has always been under suspicion but never directly implicated. Pierrot, even though his involvement may have crossed our minds, is only a child; hence, what could possibly be his motive, other than a rather brazen attempt at some misplaced attention which he so sorely lacks at home? This renders any certainties we may have up until this point dead in the water, with Haneke seemingly taking delight in further disorienting us within every new scene, playing with any conjecture we may have locked on to. Like any objective and universal truth, the evidence must not just be offered, but also be understood and processed.

Business As Usual

Haneke’s approach to Caché, as with most of his previous and later work, attempts to link staged events to the very real issues that confront us in society. Niels Niessen [3] writes, “In Caché (2005), this results in a short-circuit between the on-screen narrative and the viewer’s act of watching, as a result of which the viewer is created both as a guilty subject and as a co-investigator.” The film’s central theme is concerned with guilt, both personal and also the collective kind, and it is a masterclass on how to build psychological tension within a dramatic narrative. Haneke makes no bones about his overall intentions; he asserts that we the viewer are implicit to Georges’ actions past, present, and moving forward and one way he does this is by means of using multiple points of view; the hidden stalker cameras, the lens placed as though from Georges perspective (think of in the mirror within the elevator), Georges talking straight to camera on his TV show. This places the act of watching firmly with the viewer and not just the stalker. We find ourselves watching as Georges, but also watching Georges and his family, and just by the act of this process of looking it seems “Haneke is not pointing a finger at someone else but at ourselves. Haneke makes us see characters who represent us, from a distance,” according to Alin Farhadipour [4]. After all, Caché is a film that forces us to participate at every level. As Catherine Wheatley [5] writes, the director himself pointed out years prior to the making of Caché that his previous films had been “a polemic against the American Cinema of distraction.” In Caché, we watch the tapes and receive the pictures as would Georges. We wait in anxious, electrified anticipation for our voyeur’s next move. Anonymous as these tapes and pictures are, what awaits us around each and every corner can only bring more unrest, more tension, more chipping away at our thinly veiled truths. There is nowhere to hide, and we are all under suspicion. Guilt can always be repressed and reshaped to suit our needs; life sometimes demands it. But beware: secrets and truth have a way of finding their way to the surface, and Haneke knows just how to pry them out.

As we enter a new decade and face the unique challenges of our time, in a world of online and social media where fact and fiction, truth and falsity seem no longer to be as mutually exclusive as they once were, it makes you wonder how a film like Caché would play out with the cinema-going audience of today. The current tendency to forgo nuance on both sides of the divide (think standard western left-to-right here) and the partisan politics of a tribalistic social media, make the reading of cultural events and discourse, arts and politics, more of a tightrope than ever before. In Caché, Georges is deliberately and repeatedly placed in a position where the real truth, not his subjective truth, is the only way any of this can be resolved. Whether the revelations come through Georges’ own admissions; usually from the pressure of an increasingly worried Anne, or from the stalker forcing Georges’ hand (the tape sent to Anne which discloses Georges’ visit to Majid). In some ways, Caché plays out as a straightforward whodunnit, albeit one that holds its cards very close to its chest.

Returning to the film 15 years later, it cannot be overstated how relevant it still is, both historically and more importantly, currently. Firstly, it has rightfully positioned itself as one of cinema’s most memorable and utterly remarkable dramas to date. It’s ability to absorb and implicate the viewer so early on is a testament to Haneke’s mastery of filmmaking in this form. From the videotapes of 2005, to the world of smartphones and social media in 2020, it will have the immense power to punch through for a long time to come.

[2]. France Remembers Algerian Massacre 50 Years On: Kim Willsher, Guardian 2011

[3]. The Staged Realism of Michael Haneke’s Caché: Niels Niessen, 2010

[5]. Michael Haneke’s Cinema: The Ethic Of The Image, Catherine Wheatley, 2009