Ghost in the Shell is a paragon of anime films adapted from Manga. In these Japanese comics lies a treasure trove of layered, substantial stories that explore deep philosophical themes. In Ghost in the Shell, the questions raised by the anime from Mamoru Oshii are those of existence and what it means to be human. Blade Runner is one of my all-time favourite films and was the first to tackle this subject matter. Some would say that it handled it best and hasn’t been surpassed since, despite countless imitators attempts. I would argue that Ghost in the Shell is perhaps the only film to effectively expand on these themes.

Blade Runner’s premise posed the question of whether highly advanced cyborgs in the future who are virtually indistinguishable from humans should be viewed and treated equally. Ghost in the Shell develops this topic exponentially so as in its narrative, technology has developed to the point that humans augment themselves with advanced cybernetic prosthesis to the point where some have fully artificial bodies. The term “ghost” is used to refer to the human consciousness in these machines, taken from the Arthur Koestler book The Ghost in the Machine.

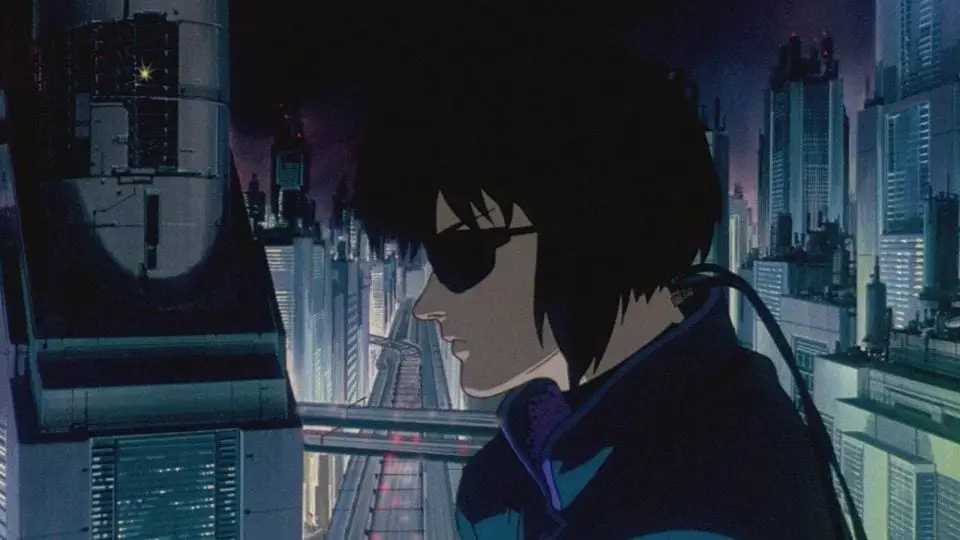

Ghost in the Shell’s central character, Major Matoki Kusanagi, is one such cyborg (although I’m struggling to choose which word best describes what she is, which in itself is a perfect representation of the main theme). Is Kusanagi still a cyborg if she has a fully artificial body, including her brain? Is consciousness enough to still be considered human? This is why the title of the film is so sharp because it actually best describes what Kusanagi is. This then leads to questions about what would be most preferable, a robust body with amazing abilities or holding on to one’s humanity?

These themes are explored through the film’s main antagonist The Puppet Master. He exists only as an artificial consciousness that hacks people’s mechanical minds and uses them for his own purposes. Kusanagi’s team, Section 9 is enlisted by the government to bring him in. However, they uncover a conspiracy and it’s actually the government themselves who created The Puppet Master to carry out top-secret, political engineering. When he became sentient, they lost control of him and he went rogue. After wandering through various networks contemplating his existence, The Puppet Master eventually decides that mortality is the essence of humanity and wishes to exist in a physical brain that’ll eventually die.

He proposes to Kusanagi the idea of merging together, as she is a kindred spirit who has also been questioning her humanity. She accepts and therefore gains all of his extraordinary capabilities. The film ends with their combined ghosts deciding where to go with their unbridled freedom to traverse the world wide web. The plot is simple and straightforward enough but the themes and ideas are dense and intricate, despite them being presented in an almost aloof manner. This adds to the style and class of this already über-cool, cyberpunk film.

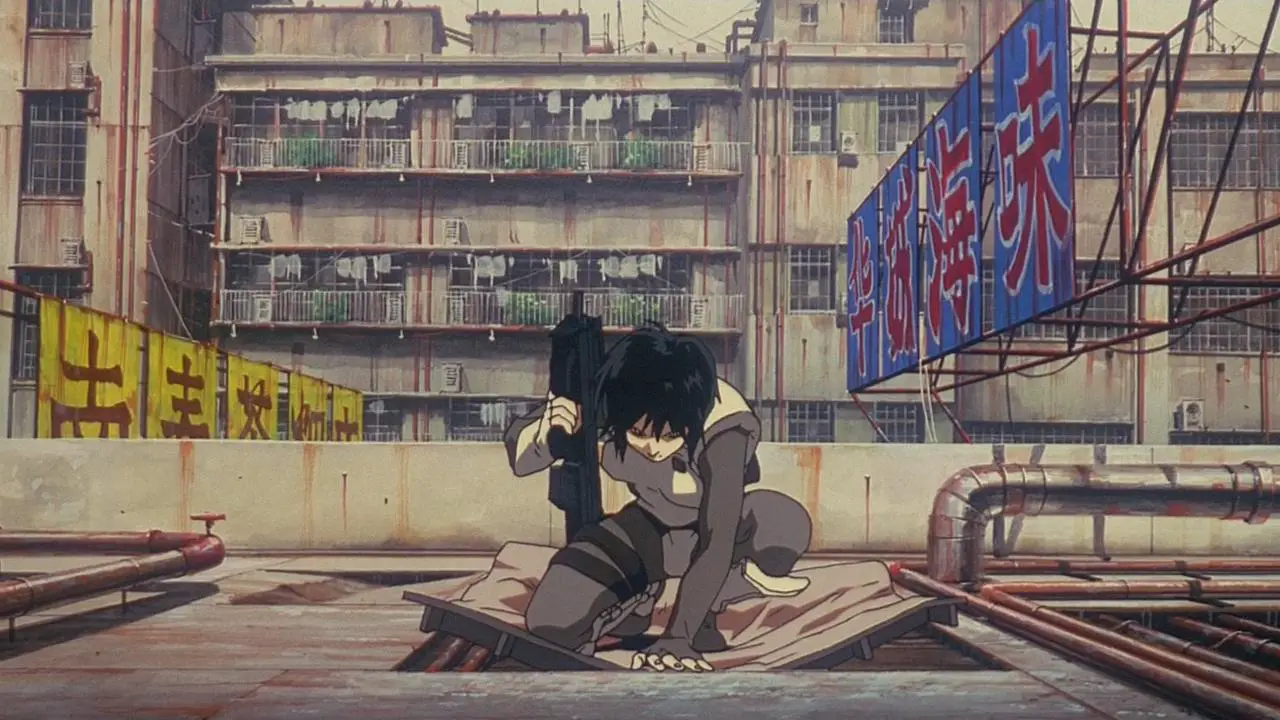

It’s very unassuming, especially considering how great an influence it would go on to have. Its subject matter isn’t the only thing that makes the film so compelling, just about every element of its design is unique and innovative. The branding of the film and the technology in its world has a very retro functionality and look to it, which will only get more stylish with age. The animation was groundbreaking at the time, as it was digitally-generated, a combination of traditional illustration with computer graphics. Realistic lighting and lens effects were also utilised to add depth of field, evoking emotion and realism.

The technique used to create the Kusanagi’s thermo-optical camouflage was particularly brilliant. The process manipulates an illustration to produce distortions in combination with its background, without altering the original shape of the image. Not only is the idea for this type of camouflage inventive in the context of the story but the technique used to bring it to life is just as savvy. It’s been endlessly imitated since, as it’s so believable in the realm of fiction. In fact, it’s become the go-to explanation for how cutting-edge camouflage works in just about everything.

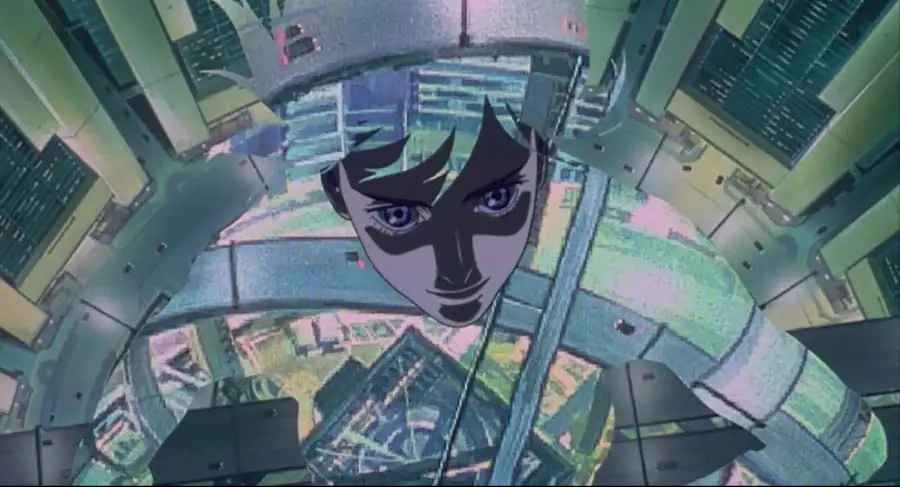

The opening credits sequence was produced by CG director Seichi Tanaka. It uses converted computer code and presents it in a language made up of romanised Japanese numbers. It’s such a slick idea and when combined with the iconic main theme “Making of Cyborg,” from composer Kenji Kawai, it makes for one of the strongest openings to a film ever. The haunting vocals are taken from a wedding chant that’s performed to dispel evil influences, with a composition that’s a mixture of Classical Japanese and Bulgarian harmonies. It’s both piercing and memorable, with lyrics that are very fitting for the film’s climax.

The action scenes are minimal and nuanced, yet powerful as well. The development team were sent away for firearms training and this helped them improve the gunfights in the film. Small, yet important details were added, such as there being sparks from bullets that ricochet off metal but not from other types of surfaces. The firepower in the film’s taken very seriously, especially in the climactic scene where Kusanagi is trying to hold her own against a tank. You really feel the impact of the shells from these futuristic guns, which adds to the tension of the narrative.

You’ll instantly recognise the code in the opening sequence from The Matrix, as this is one of the many elements that it unashamedly and openly appropriated from Ghost in the Shell. It was the first live-action film to fully utilise the action and visual style of anime in general but it’s definitely this film that it owes its biggest debt to. Ghost in the Shell was the film that directors the Wachowskis showed to their producer Joel Silver and stated: “We wanna do that for real.” There are many other visual motifs that it took, most notably the plugs in the back of the neck that are used to connect to networks and various action beats such as concrete pillars being shot to hell.

Ghost in the Shell’s influence is by no means limited to just the Wachowski’s masterpiece though. It can be felt massively in more underwhelming fare such as Steven Spielberg’s A.I. and James Cameron’s Avatar, with the latter citing it directly as an inspiration. It’s basically reflected in just about any story that involves accessing different realities or bodies, especially sci-fi ones using technology to do so. However, it’s never been captured with as much grace and finesse as in this original gem. It was inevitable that there would be a live-action, Hollywood remake and it arrived in 2017. Firstly, I have to say that although it wasn’t a huge success, I think it’s quite an underrated movie.

The adaptation was always doomed to fail, just like most projects transferring a property from one medium to another. However, I feel that it worked well as a conversion from the original but not as a stand-alone movie. It succeeded in all the visual aspects, action set pieces and score but wasn’t able to capture the magic of the source material. To me personally, this was not a surprise in the slightest and I knew it had a very slim chance of achieving this, so I was able to just enjoy it as a live-action version of the wonderful visual motifs from the anime. Despite the cries about white-washing (which most Japanese people didn’t care about, including Oshii), Scarlett Johansson put in a great performance as the Major that was commended by critics.

Michael Pitt (a favourite actor of mine) was also a great addition as Kuze, a cyborg version of The Puppet Master who was a prototype of the Major in this narrative. He had been cast aside like many others before him and this was his motive for revenge, an interesting change to the story. I agree most with James Hadfield of The Japan Times who said: “the film missed the mark, but was better than Hollywood’s previous attempts at adapting anime for the big screen.” The Matrix is a loose adaptation and will always be the real live-action version in my eyes. That’s the best way to adapt something from a different medium, loosely, because if you follow the source material too closely, you’ll most likely just end up with an odd, uncanny version of the original.

The ‘95 anime has spawned sequels in film, TV and books; it was also fully remastered and re-released in 2008 as Ghost in the Shell 2.0. It has spawned several video games and is considered to be one of the best anime films ever created, compared to game-changing sci-fi films such as Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris—an apt comparison. Johnathan Mays of Anime News Network described its combination of traditional illustration with computer graphics as “perhaps the best synthesis ever witnessed in anime.”

The cherry on top for me personally is that they chose a Brian Eno collaboration to play over the end credits. He’s a hero of mine and his ambient sound is perfect to close the film; it’s this level of sophistication that’s sadly lacking from most sci-fi projects. On the rare occasion that something from this genre has both this high level of style and substance, they make for some of the best films ever created.