An exercise in madness. A howling upheaval of the horror genre. A deeply-felt, open-hearted drama. A kaleidoscopic explosion of phantasmagorical nonsense.

One of these descriptions is not like the others, and yet, all can be applied to Nobuhiko Obayashi’s 1977 masterpiece, Hausu (or House, depending on who asks). Hausu is a film best known for its madness, arriving at a time where the Japanese film industry was in desperate need of an original voice, one that would forge a new path in a time of financial instability. In any other circumstances, it might be a wonder that it was even made and this isn’t because of its insanity, its lurid content, or the boundaries it so playfully pushes. It’s because of all the things it doesn’t say—the implications it offers, and its refusal to move in any given direction.

Hausu is a film about the weight of a promise in the wake of a war. Sure, it’s also the cult classic that you can have a complete blast with, and it will undoubtedly leave you howling, far before the watermelon man appears or the floating head takes a bite out of a character called Fantasy. Dig a little deeper, however, and you will find an open wound, barely concealed beneath a candy-coloured plaster. This is a film about expectations—how we are confined and defined by them, and how harmful they can be when they are not fulfilled. It’s also about the atomic bomb. Generations collide, and there is a refusal on behalf of those who lived through the bomb and those who came after to accept the world it has left in its wake.

It is, ultimately, not the story of the girls’ summer holiday, although we spend far more time seeing the world through their eyes than we do anyone else. Instead, Obayashi centres the plot around the character of the aunt. Through Snowy the cat (who we will return to shortly), the aunt draws the young girls to her house, and uses them for her own means, feeding off their vitality in order to restore some semblance of her own youth, as well as connecting her more deeply to the full force of the memories she was beginning to lose. She is waiting for a promise to be fulfilled. Her husband, returning from the war, and the promise of their life together. We may enter the world of Hausu through the eyes of Angel, but it is the flashing eyes of Snowy that unsettle her and her friends’ harmonious perception of the world and set the events of the plot into motion.

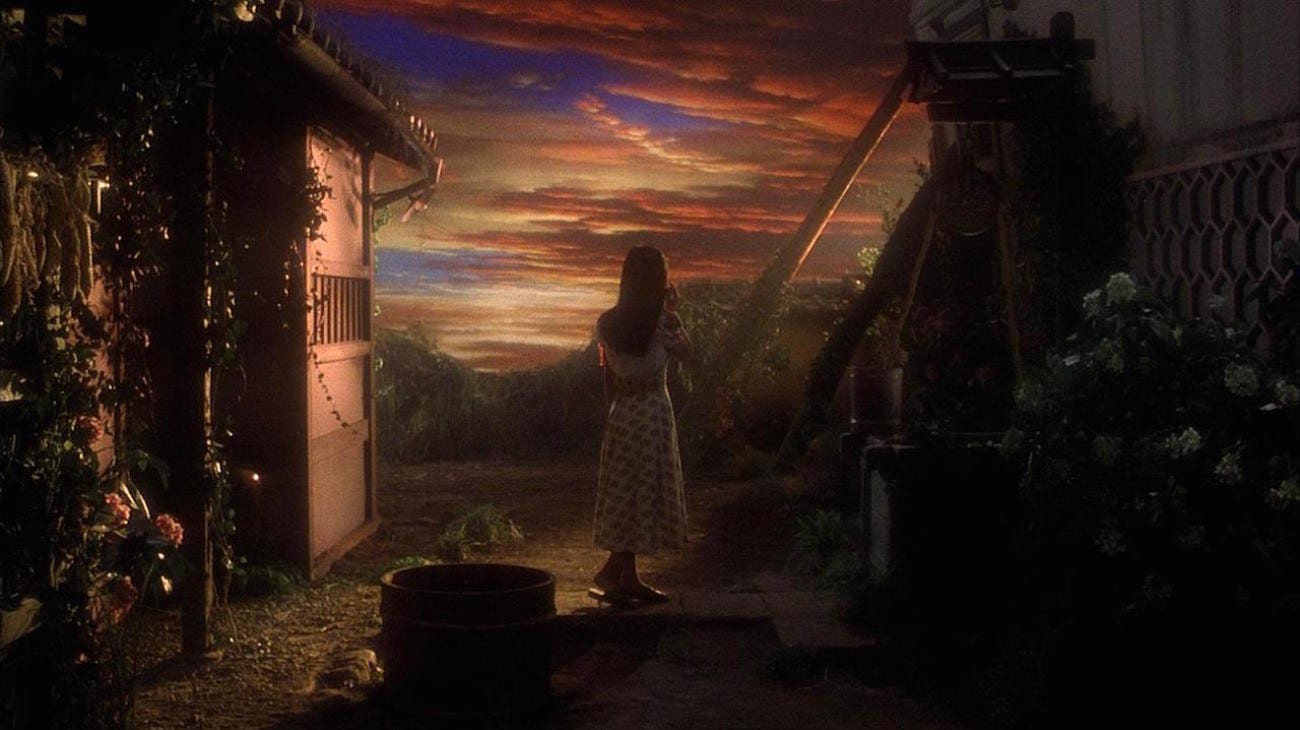

This conflict of perspective throughout the film again diffuses into the restrictions of expectation, and not only on the part of the aunt. Angel, Fantasy, Melody, Mac, Sweetie, Professor, and Kung-fu expect little more than beauty from their retreat into the antiquated countryside. Before taking the train out of the city we can glimpse a billboard behind the young girls that advertises the merits of the surrounding country, showing a painted, romantic landscape. We quickly see this painterly idyll seep into the environments that the girls find themselves in. It is all, clearly, artificial; synonymous with what the girls expect to see. By extension, there is feedback between the girls’ names (each not only confining them to one particular trait but also trapping them in the constrictions of the “stock” characters of Japanese cinema at the time) and the way they see themselves and each other, constantly reinforcing their singular attributes.

It is these expectations—of their environment, and of each other—that the aunt is able to so effectively turn against them. No one believes Fantasy when she reports strange things happening in the house. Sweetie is lured into a closet by a cute doll, before being bludgeoned by flying mattresses. Melody is quite literally eaten by a piano, in a scene so malevolently gleeful that it is a complete joy to watch. all in all, he naivety that puts these characters into these situations is harmless, stemmed only from the ignorance of the young. The aunt’s, on the other hand, is insidious. It is a product of denial: denying to believe that the world can, or should, progress in the wake of her own personal tragedy, failing to see that it is the tragedy of millions, past, present, and future.

Let’s shift our attention towards the house, for a minute. Much has been said, especially in Eastern philosophy, about the soul of a house. To many, a house never stops being a home for whatever and whoever passes through it. It retains footsteps, arguments, dreams, and dinners. In time, these might return as characteristics of the house itself, regurgitated and recontextualized as ghosts or parasites, when really, they are just symptoms of the past.

The titular mansion of Hausu is initially drained of all colour. Its faded blacks and whites are in stark contrast to the bubblegum artifice of the world outside. We see it as the young girls do: a preserved memory, shrouded in cobwebs and painted in the drab of the past they cannot know. It is only upon their entrance, however, that the house springs to life, in phantasmagorical ecstasy: cartoon candles swoop about their heads, epileptic blues and greens erupt across the screen, and, as they continue the tour, there is no sense of logical continuation from one room to the next. This is the spectacle of a house remembering what it was like to be alive.

As each girl is slowly consumed, we see the aunt, who is initially wheelchair-bound and greying, become spritely and enthused. She is able to subvert the function of various household objects to meet her needs, and the more she does so, the more the house begins to disassemble itself into explosions of outlandish violence. She might step through a fridge, and emerge in the rafters, or have a bite of watermelon that turns into an eyeball in her mouth. It’s clear that she and the house have merged, and are merely physical extensions of one another, and yet the more she uses it to feed her own fantasy of youth, the less and less it comes to resemble a house. The home that she thinks she’s preserving/building for her husband is compromised entirely by her efforts to keep the memory of him alive. Through enforcing her own memories of the past—via the seemingly sacred veneer of adolescence that her niece and her friends provide—she is in fact coming to terms with the truth of it all. In the end, the house looks like it has been hit by the nuclear blast that she has tried to keep at bay for the last twenty-thirty years of her life. This is where the cat comes in.

Snowy is the living, breathing symbol for the atomic bomb. (He’s also a good boy, and you can’t tell me otherwise). He’s the only “character” in the film who seemingly belongs to no one in particular; despite his affinity with the aunt, it is never explicitly clear that he is her cat, and he appears to the angel as a stray. Snowy can seemingly travel in time and space, getting ahead of the girls on their journey and waiting at the house for them. Towards the end of Hausu, it is Snowy who is portrayed as the enemy, and this is certainly a legitimate conclusion, with his green flashing eyes, suggested immortality, and his place at the centre of every supernatural occurrence. Yet even in the film’s final moments, as Professor comes to this realisation, it is not Snowy himself that Kung-Fu quickly vanquishes, but rather, his picture on the wall. Unlike the cat himself, the picture (which we see numerous times throughout the film) is a cold hard fact: an acknowledgement of the past that no one pays attention to until the very end. By attacking this symbol of what the past might look like, with Obayashi having already established that Snowy is the conduit for the past, unrecognised, Kung-Fu effectively buries the last remaining fact of the past—with kung-fu, of course. The cat disappears, and in the film’s final moments all that is left is the aunt, living vicariously through her niece, an angel to her. The stepmother, who Obayashi previously depicted as a truly angelic figure representative of change and growth, finally arrives at the mansion. We might hope to see her and angel finally embrace, establishing a new equilibrium through which Japan might come to terms with the horrors of the past. We might hope to see the aunt, channeling through her niece, realise the futility of her ways and accept her new place in the family, no longer left alone but remembered, and recognised. Instead, we see angel/her aunt torch the stepmother, smiling as she dissolves into atomic, green-tinged flames.

This, then, is the tragedy of Hausu. The “enemy” of the film is not Snowy, nor is it the aunt. It is denial: through the burying of the past, the subversion of the present, and the refusal of the future. In Unhinged Desire [1], Paul Roquet comments on how the film “draws on the horror genre’s exploration of the passage of emotional trauma from one generation to the next…the weight of family history on the present”, and how this trauma underpins the tragic implications of the narrative. He proceeds to say that the “the film, and Oshare herself, side instead with the crazy aunt who refuses to die and refuses to accept the denial of her desires”—but there is much more to the ending than this. There is no winning “side” on the part of Hausu. The gleeful malevolence through which the house executes those that might make it a home again is constantly offset by the melancholic tone of the film—linked, largely, to the open-hearted sentimentality of the film’s theme. Rarely ten minutes go by in Hausu without hearing it in some form or another, and all of the cast seem to sing or play their own version of it. Even Snowy meows along in a moment of shared reflection, while most of the characters are still alive and listening to Melody playing it on the piano.

This is the music of melancholy, and it is the only peaceful means through which the younger generations can connect with their older family members. The aunt remembers lyrics, and sings them softly to herself. The girls stare at the piano, enraptured by the sound. It’s the music of emotion, and in the face of ignorance, denial, insanity, and enduring unfulfilment—it connects. Obayashi’s film does not take “sides” with the aunt, just because it does not condemn her for her derangement, nor does it “side” with Angel, who would have to vanquish her connection to the past (the aunt) in order to make way for her new family. To Obayashi, no one can win this war of perspective. Hausu’s ending is, therefore, not really an ending at all. There is no victory. Only more loss, as a symptom of denial. There is no moving forward without taking a step, and the tragedy of Hausu is that the path was clearly laid out for its characters: the family, ready to take on a new stepmother, or the piano, sighing out its tune, connecting families and sharing emotions in the wake of a past that won’t go away.

1. “Unhinged Desire (At Home with Obayashi)” Blu-ray/DVD booklet for Hausu (Masters of Cinema, 2010)