I am not sure if you have noticed, but a lot is going on right now. This article is being written weeks before it will be posted, so I am not sure where we will be by the time you lay eyes on this, hopefully, a few steps closer, hopefully still working for change. Cabrini-Green is important for a couple of reasons, but the biggest reason is that I want you to relate. I want you to have a point of reference that is familiar, or that can become familiar by simply watching one of the greatest horror films of the ’90s. Maybe ever.

Candyman, as I discussed in my previous article on the movie, doesn’t always hit the mark on racial issues, especially when that’s what they set out to do, but they did a lot of things that weren’t the norm at the time. One thing they did incorrectly, but that possibly helps us here, is focus the lens of Black life on a public housing complex in ruins. The portrayal in Candyman is not the only dimension in which Black Americans exist; therein lies the failure of the movie.

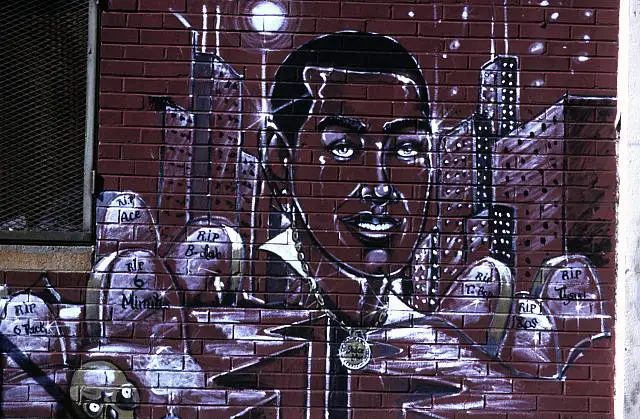

Cabrini-Green was situated in Candyman as a monster. Yes, Candyman himself was technically the monster, but I would argue that Cabrini-Green was intended to inspire a whole different kind of horror and fear. This fear was also discussed in the Special Features section of the DVD, between Tananarive Due and Steven Barnes.

The imagery of Cabrini-Green and the residents were meant to incite the fear of “other” and, in this case, that “other” was the poor black tenants. There is plenty of footage of drug dealers, and young black men meant to be intimidating. There is Anne-Marie, played by Vanessa Williams, as a young single mother, poor, scared, and suspicious of white people.

These are all damaging stereotypes, and while I hope I don’t have to explain why, I would ask you to check yourself the next time you feel a jerk of fear at the sight of a black man—maybe ask yourself where you got that fear. Anne-Marie was played as some terrified deer in the headlights character that almost became a shrinking violet when Helen enters her apartment. Is this an accurate representation of a young Black mother?

Why would Helen, played by Virginia Madsen, a total stranger, invited in, be a threat? Why would she automatically be the dominant force? If I walked into a predominantly Black community and was invited into a home, how in the hell would I find the arrogance to assume I am in charge just because I am white? Because it is my privilege. It is Helen’s privilege and she uses it.

I am white. I don’t know how it feels to walk through the world as a non-white person—but I am not without a tiny amount of perspective. I grew up in a small town, predominantly white, and with an addict for a mother. Because of my family situation, I lived in a public housing complex, though it was nothing like Cabrini-Green violence wise. There were familiar aspects though, such as the concrete blocks and utilitarian design, reminders that we were poor and different.

It was my first exposure to Black people outside of my own family. The environment was harsh for all the kids living there, but I now realize that, however difficult it was for me, it was immeasurably harder for the people of color living alongside me. Simply by being white, my life was inherently more comfortable, meaning that I could break a generational need for public housing just by doing the least. Though I would like to say, I never felt the kind of ownership of presence that Helen displays for a single moment of my time there, and it strikes me as inappropriate when I watch those interactions in Candyman. Helen is the most unaware version of herself during her visits to Cabrini-Green.

Just because Cabrini-Green and other public housing complexes don’t cover every aspect of life for people of color doesn’t mean it isn’t the reality for some. For a lot. The reason Cabrini-Green is a particularly sinister example is that it was initially viewed as a real opportunity and a great place to live. The history of public housing had been grim, to say the very least, with previous housing being referred to as “Little Hell.” Cabrini-Green and its row-house predecessors made it seem like things were turning around.

To add a little perspective, here are some of the things that seemed like luxuries to the tenants of The Cabrini-Green Housing Complex. The units had private bathrooms, separate kitchens, sturdy, fireproof construction, and self-controlled heating and air. That last one literally means that tenants were in control of the temperature of their own home. People were used to not being in control of the temperature of their own home. Please sit with that for a moment and consider what that might feel like for you.

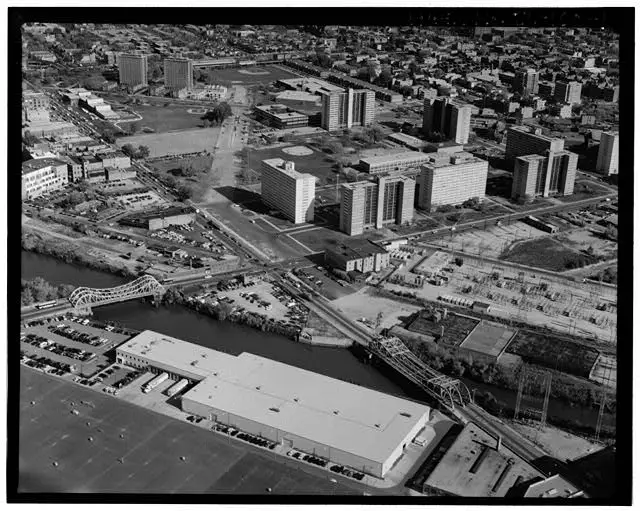

Another item of note for Cabrini-Green is that it was located just blocks away from very affluent neighborhoods, making it stand out from other public housing that would be relegated to less “nice” areas of Chicago. It is probably safe to assume that taxpayers didn’t want to see places like Cabrini-Green and be forced to acknowledge some uncomfortable truths.

White people, in general, were pushing back even from within the system. Initially, there was a quota for Cabrini-Green that stated 75% of the residents were to be white, and 25% black, however white people were not interested in integrated housing at the time, as reported by The Chicago Tribune. Pair the pushback for integration with the boom of the African-American population in Chicago you get the final picture of Cabrini-Green: the first real example of public housing for predominantly African-American residents.

Now we can start to talk about the cracks in this situation. There were a lot of things people liked about Cabrini-Green, including elevators and open-air balconies that were meant to create a feeling of unity and community. Imagine what elevators must be like when you previously couldn’t even decide the temperature of your own home. However, you start to see where different treatment comes into play.

In a YouTube video from Cold Crash Pictures, there is a discussion about the address markers for the buildings. They were spray-painted in a military-style, utilitarian looking manner despite being more costly and less aesthetically pleasing than the metal numbers the architect wanted to use. The architect was informed that the housing needed to look as utilitarian as possible. After all, there were wealthy white people right around the corner, and would they want to see their tax dollars go into any kind of luxury such as beautiful number plates?

I would say the fall of Cabrini-Green began right around the opening of Cabrini-Green, and I think it starts with the systemic discouragement of a family unit. You see, in public housing, you can only make so much money, and if you were to marry the father of your child, you would likely price yourself out of the housing. Now, having two incomes does not mean you can afford a place to live; it just means you are too wealthy for the government to help.

So, women often had to choose between their husbands or a home for their children. According to Thirkield Garrett’s article “Cabrini-Green and the Target Projects Program,” “Eighty percent of the families being housed at Cabrini-Green are single-parent families, and 70 percent of the single parents are under 24 years of age.” These numbers are not reflective of a government that seeks to help people get to a better life.

What possible good could come from creating single mother households and preventing marriage? There is nothing wrong with being a single parent; there is something wrong with the government deciding that life for you. The disregard for the family unit is the most significant indication that there was no real help here for the Black community.

Eventually, all of the things that once made Cabrini-Green enjoyable would become a downfall. The residents were essentially dropped off and then left to fend for themselves. There would be no routine maintenance of the elevators, plumbing, electricity, trash, sewage, pest control, you know, normal things that most people get when they rent an apartment.

When units were vacant, they were often left open to anyone who wanted to come in and sell drugs, use drugs, or any other form of activity not suitable for children to grow up near. It was for these reasons that Cabrini-Green ran itself into the ground. There was little to no resources to help the residents; most of the advocacy came from within the community. The lack of resources is another way of, again, saying that the government abandoned this community. Was it negligence or was it willful ignorance?

When it became clear that there were issues with illegal activity in Cabrini-Green, there was no such thing as reform. There was no help, no rehab, no family reconciliation. Instead of addressing the issues and looking for ways to repair the situation and prevent future problems, the government would perform massive sweeping raids on the complex.

These raids are mentioned briefly in Candyman when Helen asked how they caught her assailant so quickly. These raids were not only ineffective; they were also extremely costly to the taxpayers, the same taxpayers that everyone was worried about while spray-painting addresses on buildings.

So, in summary: Poor Black citizens were given housing that seemed like a fantastic opportunity. Unfortunately, the government either didn’t care about the tenants or purposefully chose to abandon them in a building that needed just as much upkeep as any other apartment complex ever. Marriage was systemically discouraged in the black community when they had to choose between marriage or a home for their children. Gangs were allowed to overrun the complex completely; the only thing the government did was perform costly and ineffective raids. These are all beautiful experiences for the MANY children living there and were probably in no way traumatizing. So tell me again how the system isn’t built to oppress people of color?

I want to add that I was given a fantastic amount of research from a fellow writer, and believe me when I tell you I am giving you the PG version of Cabrini-Green. There are endless accounts of violence and incredibly heart-breaking incidents. Through additional research of my own, I have found so many instances of the Chicago Housing Authority making decisions that led to the downfall of Cabrini-Green step by step. I would urge everyone to look up Displacement Through Discourse: Implementing And Contesting Public Housing Redevelopment In Cabrini Green by Deirdre Pfeiffer.

There is a perfect formula for poverty, racial disparity, governmental apathy, and willful ignorance to create situations like Cabrini-Green and many other public housing complexes. We have been doing this for a long time; things are not working, so are we going to continue being the definition of insanity, or are we going to step up together and demand sweeping change?

On a personal note, no matter what you see in the films we discuss, there will never be a greater monster than human beings. We can come up with any number of alien creatures, blood-thirsty monsters, wolves, boogeymen, but at the end of the day, each one of those is simply a metaphor for something terrible a human monster has done. After the things I have read and learned in the making of this article, Dracula has nothing on a lousy human being.

I find it really Interesting to see the American perspective on these issues. I am a British person of colour and if you were to visit the United Kingdom and see the Area in which the original Story The Forbidden is based you would be likely to find the housing project to be very much so Mixed specially being in Liverpool. Nice article though.

Thank you for taking the time to comment, I really appreciate it. I agree and am glad to have your perspective on public housing. I had not heard the bit at the end where you talk about what Clive Barker said, but man, that sure fits and does add to the scariness of the film. I understand, lol, I could write 5 more articles and still probably never be done talking about Candyman. I won’t put everyone through that, though.

I really liked the part where u talked about how the govt. makes choices for u when someone seeks government help. I grew up in a public housing project in Pennsylvania and it’s a place that’s also very difficult to get away from. That’s the one thing higher class people never understand. A high percentage of these people don’t want to be there, don’t want to bend over backwards for a few crumbs from the government, yet they act like people r getting a free ride. There is more than enough for everyone if others r not so greedy. If the rich people keep all the money among themselves then what will the poor have. It’s also why capitalism fails….like the snake eating it’s own body. The poor people give thier little bits of money to the rich and it never circulates back out to the poor as the rich build wealth. To a point that the poorer class has no more to give, then the snake eats the second part of its body (middle class) until they have nothing more to give…all the while the rich people sit on loads of money. Until finally they start cannibalizing themselves. Just like monopoly too lol there’s only one winner eventually. Class discrimination and those other secret meanings in Candyman r the reasons this movie seems so threatening and creepy giving the feeling of how horrrible would it be to live there and like that, now with some ghost story coming to truth. Clive Barker said something in the original story about the topic along the lines of “a perfect tragedy with people living thru something terrible, but never realizing what they r living thru bcuz they can’t see outside of what they r going thru. Only when u see it from above can u really understand. Anyway, great article about a great movie, I could rant forever about those subjects lol