The following contains spoilers for Dark Season 3, and indeed the entire Netflix series

By its very nature, science is a cold, rational, logical form of enquiry. It deals in facts and trades in proof. Speculations, however sensible or wild and fanciful, must be empirically proved to be considered real and concrete.

And yet, it is two of quantum physics’ most outlandish and unproven concepts that have fired the imaginations of storytellers working in the field of science fiction. Time travel and alternative dimensions have since become a staple of the genre: a way for writers to satire their contemporary time, explore alternative ways of living, reassess the past, and outline a predicted future (whether utopian or dystopian). In this way, time travel functions as a parable: a warning of what we need to change and the consequences involved therein.

In fact, time travel and alternate dimensions, as prime sci-fi fare, have become so embedded in our popular consciousness, the tropes so utterly predictable, that it takes something with a real sense of originality in its storytelling and use of such tropes to make these fascinating concepts vital once more in fiction.

Dark is just such a show.

The third and final season of Netflix’s cult sci-fi mystery saw Dark add a crucial new focus on alternative universes to its thematic and formal temporal knots. Rather than complicate matters further, by the series’s end, the addition of these alternative universes actually became the key to unlocking the show’s central mystery: the origin of the knot that keeps the inhabitants forever bound in their infinite loop of trauma.

In this article, I will be taking a closer look at how Dark uses the concept of alternate dimensions, how it meaningfully links this to the show’s thematic bedrock of time travel, and how the use of time travel and alternate dimensions is ultimately in the service of something science doesn’t account for in its conceptualisations: the difficulties and complexities of negotiating intense human desires.

The Forking Paths of Winden

When we left Jonas at the end of Dark Season 2, he was watching his beloved Martha die after being shot by his future self, Adam. Except Martha wasn’t really dead—well, not exactly. Another version of Martha from an alternative dimension appeared at that moment to whisk Jonas away back to her version of reality.

The word ‘alternate’, plus the fact that Jonas’s world is the only one we have focused on up to that point, leads us to assume that Jonas’s dimension is the ‘correct’ or ‘authentic’ one.

And we’d be wrong.

The concept behind alternate dimensions, by the nature of its complexity, is something that’s extremely difficult to sum up in a few simple sentences. However, a brief definition of modal realism does offer some clarity: ‘all possible worlds are real in the same way as is the actual world’. The implication is clear: if a vision of a world is possible, then it exists. And not in a hypothetical sense, either, but in actuality. It exists as our world exists.

What is it that makes a ‘possible’ world, and what can that possible world include? Physicists have debated the concept for many years, with sceptics denying its validity as a scientific concept while its proponents point to the equations underlying their belief (whilst acknowledging the near-impossibility of verification).

In popular fiction, a longstanding idea is that multiple universes are created as the opposite result of the choices we make. For example, if I choose to have coffee, this creates a new, separate universe where I choose not to have coffee and even another one where I choose to have something different altogether. Some fiction speculates that it is only significant actions and choices that lead to alternate universes forming.

The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges was perhaps the first to use the concept of multiple realities in fiction. His 1941 short story ‘The Garden of Forking Paths’ revolves around a spy who is confronted with the truth of the legacy of his grandfather, and a novel and a labyrinth that turn out to be the same thing: the titular garden. The spy is told by a sinologist:

In all fictional works, each time a man is confronted with several alternatives, he chooses one and eliminates the others; in the fiction of Ts’ui Pên, he chooses—simultaneously—all of them. He creates, in this way, diverse futures, diverse times which themselves also proliferate and fork […] In the work of Ts’ui Pên, all possible outcomes occur; each one is the point of departure for other forkings. Sometimes, the paths of this labyrinth converge: for example, you arrive at this house, but in one of the possible pasts you are my enemy, in another, my friend.

Of course, the sinologist refers to fictional works, which suits our needs in that Dark is a work of fiction. But, as within the world of Dark, the proponents of modal realism and multiverses understand this to be very much real. It also realigns these metaphysical concepts with the human element: it is, after all, from us and our choices that these forking paths emerge, whatever the physics behind it all.

Dark plays with this idea of the significant act creating alternate universes, linking it back to very human ideas about trauma, how we react to it, and how those reactions can influence the future course of not just ourselves but of those around us.

As we now know, it was not Jonas’s reality that was the dominant or original dimension. Nor was it the alternate Martha’s. Perhaps the biggest shock to come out of Season 3 was that both of these dimensions in actuality were only forking paths from Winden’s mysterious garden.

A Journey Through Time via the Heart

We now know that Tannhaus, author of the in-universe book A Journey Through Time—and, through a paradox in Jonas’s dimension, the inventor of the time machine (as copied from the already created machine shown to him by the future version of Claudia Tiedemann)—is responsible for the incident that led to the creation of Jonas’s and alternate Martha’s dimensions: paths forking off Tannhaus’s dimension of origin.

In 1986, TV scientist, clockmaker, and time obsessive H.G. Tannhaus argues with his son, Marek, who believes that the elder Tannhaus never gave him any real love or attention because he was too wrapped up in his scientific obsessions. Fuming, Marek leaves his father’s house, taking his wife, Sonja, and their daughter, Charlotte. Tragically, his rash decision to leave his father’s house there and then led to a situation where his car crashed off the bridge, sending the three to their deaths in the water below.

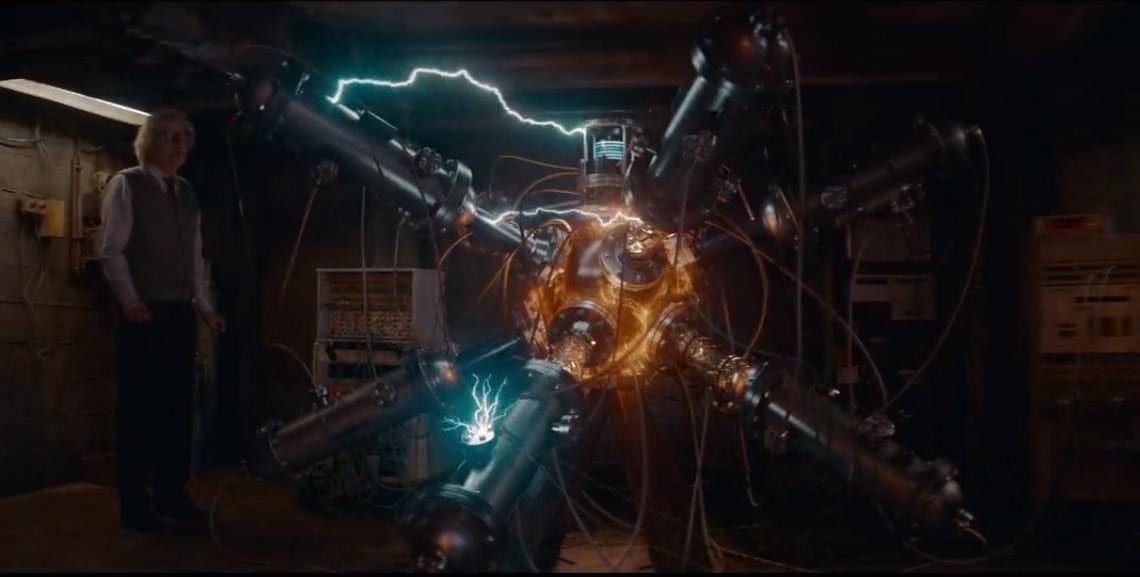

Tannhaus, racked with remorse and guilt, turned to his obsession with science in the hope that he could create an actual time machine. If he could go back in time and prevent his son and his family from driving away that night, he could, in turn, prevent their deaths and rebuild his relationship with his son. However, when his time machine is finally turned on, an unforeseen error occurs and, unknown to Tannhaus, causes the creation of the alternate dimensions inhabited by Jonas and Martha.

While it could be argued that the reveal of this dimension, saved for the Dark series finale, was a little rushed and opened up more questions—yes, Claudia rationalised that there must be another dimension, but how did she actually get there? And how did she discover that it all originated with Tannhaus?—there’s a certain appropriateness in everything originating from Tannhaus. Despite appearing to withdraw away from the main narrative points in Season 2 and the majority of Season 3, he was always there in the background, haunting the atmosphere like an echo.

His adopted ‘granddaughter’, Charlotte Doppler, negotiating the existential crisis of the revelation that Noah is her father in Season 2, is a reflection of the crisis Tannhaus felt in losing his biological granddaughter, Charlotte, in the origin dimension. The revelation in the third season of an even elder Tannhaus than H.G., in alternate Martha’s dimension, who meets travellers from the future and is as passionate in his belief about the viability of time travel as his descendant, is an indicator of who this alternate dimension’s unintentional creator really is.

Interestingly, by using Tannhaus (‘H.G.’ being a reference to H.G. Wells, author of The Time Machine) in this way, Dark puts science in service of the human heart, as opposed to humans finding themselves at the mercy of a cold, vast, and indifferent universe. Tannhaus’s desire for catharsis and a second chance to redeem the side of him that failed those he loved is the catalyst for him to move from theoretical physics to physical experimentation.

And yet, Dark does not present time travel in a fanciful or a high-fantasy way. Co-showrunner Jantje Friese has spoken about the sheer volume of research she did in this area during the writing of the show, and the show is always respectful in its use of science. The fact that it is Tannhaus, a scientist, who sparks the birth of the alternate dimensions, helps give the idea scientific credibility. His creation comes out of his scientific knowledge, and yet the fact that it is an accident that triggers the alternate dimensions reaffirms that for all the great wealth of our knowledge of physics, this is still just a small speck of what there is to know. It punctures the hubris of the human idea of the depth of our own intellect. It also suggests that, unlike the idea that multiverses are created like forking paths displaying all our differing choices, it was actually a scientific interference with laws of physics that forced the creation of the new dimensions.

And just like Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks: The Return, such interventions in the laws of time have serious, unforeseen consequences.

Best of All Possible Worlds?

As we know, the origin universe forked off into two new dimensions: one containing Jonas and Martha, and the other containing the alternate dimension Martha. Both Jonas and alternate Martha become aware of the time loops they are caught in, resolve to end them, and in the end are only successful in strengthening these time loops further and helping to establish them over and over in perpetuity.

As their age progressed in a chronological manner, contrary to their leaping back and forth through time, and as the accumulated traumas, pain, fear, and loss weathered and wore at their souls, they found themselves transformed into ‘new’ people: the physical embodiments of all that pain. They became Adam and Eva.

The Biblical reference is obvious, but it also betrays a strong sense of solipsism. Think of the hubris it takes to think of yourselves as the first people of a new world and then name yourself accordingly. But there might be more to it than that, too.

In Episode 5 of Season 2, Adam tells his younger self as Jonas that:

God is our antagonist. We are creating a world without time. Without God…in short, the God mankind has prayed to for thousands of years, the God that everything is bound with, this God exists as nothing other than time itself. Not a thinking, acting entity. A physical principle with which you can no more negotiate than you could with your own fate. God is time. And time is not compassionate.

The names ‘Adam’ and ‘Eva’ might be ironic displays of rebellious intent against the God of time, but they also betray a messiah complex. Because if you kill God to create a new world, in creating that world you yourself would become God. That can have a heady attraction in itself. Look at the way both Adam and Eva become absorbed in their chamber in gazing at paintings of tortured, naked souls in hell or, indeed, the Biblical Adam and Eve. Look at the evangelical way they preach to those they manipulate like pieces on a chessboard, promising a better tomorrow (or indeed, no tomorrow) as a reward for the impossible cross they have to bear and the sorrow they have to endure in doing ‘God’s’ work. They say you eventually become what you hate as you get older. Perhaps Adam and Eva are evidence of that. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Interestingly, the German polymath Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz believed that God picked the best of all possible worlds to be our actual world. But this picking suggests a subjective choice on God’s part: a world that God believes is best based on personal taste as opposed to an objective approach to the greater good for the largest number of people. No one said a God couldn’t be fallible, and if we look over Adam and Eva’s actions across different times and dimensions, it’s fair to say that their ‘best of all possible worlds’ is not for the greater good either.

The Eternal Present of Solipsism

Imagine that, by virtue of having the ability to time travel and jump dimensions, you are able to see how everything and everyone is connected, what torments and hurts they will experience, and what joys and desires drive them. Seeing how everything connects to everything else—how the web weaved by the spider of time shows simultaneously the importance of the smallest of actions and also, paradoxically, how insignificant we personally are in the larger scheme of things—it is easy to assume such an observer would find themselves quickly stripped of ego, convinced of the need to work towards the greater good.

Therefore, it is also reasonable to assume that it would take someone with extremely solipsistic, self-absorbed qualities, magnified to perhaps quasi-psychopathic levels, to face this web of trauma and torment and not only allow it to continue over and over in an infinite loop but actively work to perpetuate it in service of their own heart’s desires.

Adam and Eva, of course, do not stand outside of the loop and are subject to the same traumas the loop inflicts as much as they are responsible for perpetuating them. Perpetuating others’ pain is perpetuating their own to a point. But still, their end goal is biased in as much as they are not looking to make the ‘best of all possible worlds’ for the whole but the very few—themselves.

This solipsism may be a result of the physical nature of how they experience time and space. Trying to emotionally navigate time in our everyday linear experience of it can be overwhelming enough sometimes. Imagine, then, having to sail across the treacherous waters of past, present, and future, having to remember what everyone does, and when and why they do it. This non-linear perception of time would be enough to scramble anyone’s mind.

You might even find yourself beginning to be distanced from past, present, and future as three separate states, which in turn would distance you from other people’s pain as traumatic events occur to them at these various stages in time. In fact, you might see all time as one and the same, a single block of ‘now’ that you experience only as you live it in the moment. As Borges wrote in “The Garden of Forking Paths”, ‘I reflected that everything happens to a man precisely, precisely now. Centuries of centuries and only in the present do things happen; countless men in the air, on the face of the earth and the sea, and all that really is happening is happening to me’.

It is not quite correct, though, to say Adam had lost all sense of the future. His desire to destroy time is structured by his understanding that he is working towards that goal—that everything is moving towards his objective, like a black hole swallowing matter. And yet, through the intensity of his desire for the obliteration of the loop, his conviction of success details the future as a set state, as inevitable as the lives whose choices are already set in stone by the loop, as opposed to an open, malleable period of time. As Borges wrote, ‘the author of an atrocious undertaking ought to imagine that he has already accomplished it, ought to impose upon himself a future as irrevocable as the past’.

This hatred of time, for Adam, is also fuelled by the trauma of the heart. Adam is the older version of Jonas, and as we know, Martha died in Jonas’s arms after being shot by Adam. It’s a loop in itself, but the pain Jonas experienced in seeing Martha die at the hands of Adam twisted and manipulated him into the being that became Adam. At this point, Adam realised that to achieve the transformation into himself, he needed to go back in time and kill Martha to set Jonas off on the path to becoming himself. For Adam believes he has the answer to ending the time loop, and he will not discover that unless he sets Jonas off on the same path he went along.

Where Adam went wrong is in his failure to realise that his world is not the actual world, the dimension of origin, but is in itself a forking path away from Tannhaus’s failed time experiment. It is not just a matter of travelling from his past self into the person he has become at that moment; he will continue to transform as he continues to age. In this way, living is a continuous process of becoming. But, as to eradicate time is to effectively commit suicide, it is curious that Adam never questions how he can be successful when he’s still there, existing. By his very existence, he is doomed to fail.

He is shocked and dismayed when his attempt to destroy time (by killing what he believes is the origin of the knot in time—the child of Jonas and alternate Martha) does not work. But if he’d thought it through, he wouldn’t have been surprised. If past, present, and future all seem to exist at once, then for time to not exist, he would not exist with it. Adam was guilty of typical human hubris that he could change something that was beyond his scope at that point to change.

As for Eva, she is playing everybody around her like a pawn on a chessboard with only one goal in mind: to keep the temporal status quo in place so that the child she had with Jonas will stay alive. It’s an interesting dilemma: the maternal instinct against the greater good of a whole town of people. She is not willing to obliterate these people like Adam is, but she is seemingly happy to perpetuate the loop of misery with no qualms as long as her son remains the same. Adam has to do the same; he has to perpetuate the loop out of a kind of nihilistic selfishness. He has to allow his younger self to become him in time so he will know what needs to be done—the destruction of time itself. For Eva, it’s a different kind of selfishness, one borne of love.

As a parent myself, would I do the same? We’re talking hundreds of people at least in infinite pain against one child, but who would be willing to sacrifice their own child? I’m not sure I’m comfortable to answer either way, and it’s this moral ambiguity that gives the actions of Adam and Eva a really uneasy tension.

A tension all for naught.

To Resolve the Longings of the Heart

If Adam and Eva were led by their hearts to their actions, they were distracted by their obsession with time. Yes, their son gave them an awareness of and link to each other’s dimensions. But it was time that became their overriding obsession. Adam wanted to destroy time by ending the loop. Eva wanted to keep everything in the loop in place so as to keep her son alive.

What was beyond their comprehension (and ours until the end of Dark) was that neither Adam nor Eva’s realities contained the origin of the knot. The answer lay not in time but space—or, rather, a third dimension that both Adam and Eva’s dimensions forked from: Tannhaus’s dimension.

Ultimately, the loop would remain whilst Tannhaus made a time machine in the origin universe. Adam and Eva’s forking paths would be borne from this decision, and both Adam and Eva would ensure the loop was perpetuated to infinity. For the loop to end, Tannhaus would have to be prevented from building his time machine.

What I like about this idea is that, rather than being just a story about going back in time and changing the past to change the future (which we’ve seen many times before) or a satire of our world through the use of a parallel universe, Dark instead pursues this fascinating question: to what extent are time and space linked together, and is to change one also to change the other?

Now, the easiest way for Tannhaus to be prevented from building his time machine would be to kill him, but Dark isn’t cruel enough to do so. Alternatively, the show could have nodded to its first season and had Jonas and alternate Martha show Tannhaus a working time machine so he can modify his own into a working model. They could then allow Tannhaus to go back in time and prevent his family from leaving that fateful night. But Jonas and Martha have seen the perils of time travel. It wouldn’t make sense for them to encourage any further time travel and risk starting a new loop.

What Dark chooses to do is much more satisfying and links its resolution to the drives that pushed Tannhaus, Adam, and Eva to utilise time travel in the way they did. Adam, having been made humble by his failure to eradicate time and now in the knowledge of the loop’s origin, goes back to his younger self, recognising his more innocent idealism, and appeals to his better nature, free of the nihilism that was to twist Jonas into Adam. There’s a real pathos to Adam’s realisation of how far he had travelled from his younger self into the darkness.

Jonas, in turn, rescues Martha from being recruited by Sic Mundus. They then travel in time and across dimensions and appear before Tannhaus’s son, Marek, and his wife, Sonja, in front of the bus stop where Ulrich and Hannah had once wished for a world without Winden (in a different time and a different space), convincing them to go back and make up with Tannhaus. Marek believes he’s seen angels. If only he knew about Adam and Eva’s messiah complexes! Jonas and Martha disappear into the ether, as their forking paths cannot exist if Tannhaus does not build his time machine. And now he has no reason to even consider the matter. His heart is full; he has his family back.

As for Jonas and Martha, they have almost made a suicide pact together. They knew that preventing the creation of the time machine would eradicate their respective dimensions as well as themselves. But whereas Jonas would become Adam on the basis of the strength of his love for the Martha of his world and his unresolvable pain and fury at her death, now they are together, sharing their love and loss in one last climactic moment. To the laws of physics, they do not belong, but they will always have each other in this one final intimate moment.

‘We’re a perfect match. Never believe anything else.’

The heart wants what it wants, after all.

Of course, for Leibinz it is the idea that God is infallible that leads him to argue this is the best of all possible worlds. God is omniscient and omnipotent, so of course he would choose the best world because if he didn’t that would imply that either his knowledge or his power were constrained, and so on. It is a rather circular argument!