When Ennio Morricone died on July 6 at age 91, many news outlets recognized his collaborations with Sergio Leone as his most notable work, specifically 1966’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly. Morricone of course continued working well beyond that year, decade and century. In fact, just four years ago, Morricone won the Academy Award for best musical score for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight with nearly 500 film composition credits behind his name. Between these time frames, Morricone flourished as a composer, and perhaps his greatest creative period was during the 1980s and 1990s—the period where Hollywood came calling and Morricone was as eager to work with American directors (Brian De Palma, Barry Levinson and John Carpenter) as they were to work with him.

This is not a “best-of” list of this period but rather a list of 10 of my personal favorite Morricone scores during these years, most of which were for Hollywood studios and directors. Because he was so prolific, there are titles I love from this period I had to leave off (Bulworth, In the Line of Fire, U-Turn) because I only wanted to list 10. Some you’ll agree with and some you won’t but that’s the great thing about Morricone: he loved to work and we’re all richer for it.

Bugsy (1991)

Barry Levinson’s 1991 holiday release Bugsy marked the third gangster/crime picture scored by Ennio Morricone since 1987’s The Untouchables, the second being 1990’s State of Grace. Unlike the thumping musical sound the composer provided for the Al Capone picture, Morricone provided a more subdued musical accompaniment for this story of another real-life gangster, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel here played by Warren Beatty. Morricone’s score features heavily on the romantic aspect of Siegel’s life—his dreams to build a casino in the desert and his fiery passion for his main squeeze, the glamorous Virginia Hill. It’s a more reflective gangster picture than the De Palma entertainment and the score invokes the memory of Siegel the man—and his large dreams. Key track: “Act of Faith #2”

Casualties of War (1989)

Looking back, one wonders what Columbia Pictures was thinking of when they scheduled Brian De Palma’s dour, intense, unflinching and powerful Vietnam drama Casualties of War in the middle of a summer movie season featuring Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and When Harry Met Sally. Clearly audiences wanted happy movies that season. Casualties of War, a story featuring kidnapping, rape and murder, was not going to win the weekend box-office when it opened (Uncle Buck took the title) despite critical acclaim. In the years since its release it has discovered new life, and one of the reasons audiences have reacted to it is the powerful, haunting score by Morricone, which like Once Upon a Time In America and The Mission, uses the pan flute to tremendous effect. I can’t remember ever seeing Honey or Sally since its release but I will revisit Casualties of War every once in a while mainly because Morricone’s score is truly a heart-breaker, and I mean that as a compliment. Key track: “Elegy for Brown”

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

In a 1989 episode of the ABC sitcom Head of the Class one of the characters asks a female classmate he’s crushing on to go see the new Italian movie Cinema Paradiso. He couldn’t have chosen better. The Giuseppe Tornatore story of a boy in love with the magic of movies won acclaim and made audiences weepy the world over. The movie’s most known theme, “The Love Theme From Cinema Paradiso” was actually composed by Morricone’s son, Andrea and it was so popular it was released as a single throughout the world. It’s incredible to note that this score, which is regarded as not only one of Morricone’s most beloved, but one of the best scores of all time, was not even nominated for an Oscar. Scandalo! Key track: “Cinema Paradiso Theme”

Disclosure (1994)

Previously I looked back at Barry Levinson’s 1994 sexual thriller Disclosure and determined it was an entertaining adult drama which raised some serious questions in the current national climate. Clearly the story sided with the male protagonist and painted the main female character as a calculating, manipulative sexual predator. This definitely makes Disclosure a product of its era along with the fact it is one of the last big-budget Hollywood movies that would be scored by Ennio Morricone. Although he didn’t completely leave American movies behind, this period was when the composer decided to begin focusing primarily on international personal pictures and Disclosure would be the last movie he would ever score for Warner Brothers. At this point in the ’90s composers such as Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard were emerging as top go-to talents but Morricone still proved to be the master with this score, which features some of his most unusual writing of the decade. There’s a tranquil family theme that opens the film which then gives way to svelte strings representing uneasy inter-office politics. My favorite parts of the score feature a drum and plucky string arrangement underneath a soaring prominent heavier string representing triumph for our hero. Key track: “Preparation and Victory”

Lolita (1997)

Speaking of another film which wouldn’t get made today, Adrian Lyne’s Lolita barely even got released in the end of the ’90s. The second film adaptation of Vladimir Nabakov’s controversial novel (the first film adaptation appeared in 1962 from Stanley Kubrick) faced many obstacles finding its way to screens in 1997. The subject turned many American distributors off, and at the end of 1998 the film was broadcast on the premium cable network Showtime (later of course, home to Twin Peaks: The Return). One person who wasn’t scared by the material was Morricone, who crafted one of his loveliest and dreamy scores of his entire career for Lyne’s film. A solo viola is heard in many of the film’s moments of wistful longing leading to a full children’s choir, which presents itself at the movie’s shattering end. Key track: “Finale”

Love Affair (1994)

1994’s Love Affair was a star vehicle for Warren Beatty and his wife Annette Bening but neither critics nor audiences found much to love about the movie. Its only saving grace is the magnificent, tender score by Morricone that ranks up there with “La Califfa” from Lady Caliph among his most movingly melodic. 1994 was a memorable year for Morricone—as this list can attest, he has heavily in demand to score American films. For Love Affair Beatty worked with the composer for the first time since Bugsy (which earned Morricone an Academy Award nomination) but the response was quite different. 1994 would prove to be the last year Morricone would score multiple Hollywood projects. It’s a shame because his Hollywood work ranks among some of the best of his long career. If you should catch Love Affair (his second-last project for Warner Bros.) forget the stilted dialogue and soap opera lighting and just enjoy Morricone’s music. Key track: “Finding Each Other Again”

Once Upon a Time in America (1984)

Sergio Leone so respected Morricone that he would film his movies to the composer’s already written and recorded music. On set, Leone would play the maestro’s music for the crew and actors and make the movie that way. Entire sequences were filmed in choreography to the music, which Morricone would dream up from conversations with Leone before a single frame was filmed. It was an arrangement that worked for the duo on Once Upon a Time in the West in 1968 and they stayed with it for their last collaboration, Once Upon a Time in America. Among the themes devised by Morricone were “Cockey’s Theme,” which was performed on pan flute and “Deborah’s Theme,” one of the composer’s most well-known themes. Leone was deeply hurt, however, when Warner Bros. cut his 227-minute epic down to 167 and never planned another film until he decided to make Leningrad: The 900 Days in 1989. Sadly, Leone died in April of that year. We’re certain that had the project gone ahead, Leone would once again be gliding his actors and camera to the beautiful melodies of Mr. Morricone. Key track: “Amapola”

The Untouchables (1987)

It’s not uncommon for a director to let the composer help tell the story with music, but it is rare when a director leaves it to the composer to solely tell the story—or at least part of it. Steven Spielberg often lets John Williams just use music to forward the narrative in their collaborations and for 1987’s The Untouchables, director Brian De Palma let Morricone’s music take over the movie’s most suspenseful dialogue-free sequence (all seven minutes of it): a train station showdown between cops and gangsters with a baby in a carriage between them. For a movie filled with at least five memorable themes (a theme for Al Capone, a mournful theme for poor beat cops, a triumph theme and a thumping main theme which represents gangland Chicago itself) the train station standoff is perhaps its most remarkable in that it utilizes a children’s chime throughout and its nervous strings and flute gradually introduce themselves as the cue culminates in Bernard Herrmann inspired tight, shaky strings and back to the children’s chime. It’s Morricone at his most brilliant and demonstrates why so many directors wanted to collaborate with him. Key track: “Machine Gun Lullaby”

Wolf (1994)

It seems that every director has wanted to work with Morricone at some point, and in 1994 Mike Nichols got his turn with Wolf, a better than you might remember creature/animal thriller starring Jack Nicholson and Michelle Pfeiffer. This is not unfamiliar territory for Morricone after having scored White Dog and The Thing in the early ’80s. This would be the composer’s second-last work for Columbia Pictures with 1997’s U-Turn being the last. This score combines mystery with romance and creature combats with better results than Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein would later that year. During Nicholson’s transformation scenes into the wolf, Morricone supplied busy percussion heavy action cues and for the Pfeiffer scenes he uses a mysterious and lush blend of synth and sax, which is pure Morricone. Key track: “The Barn”

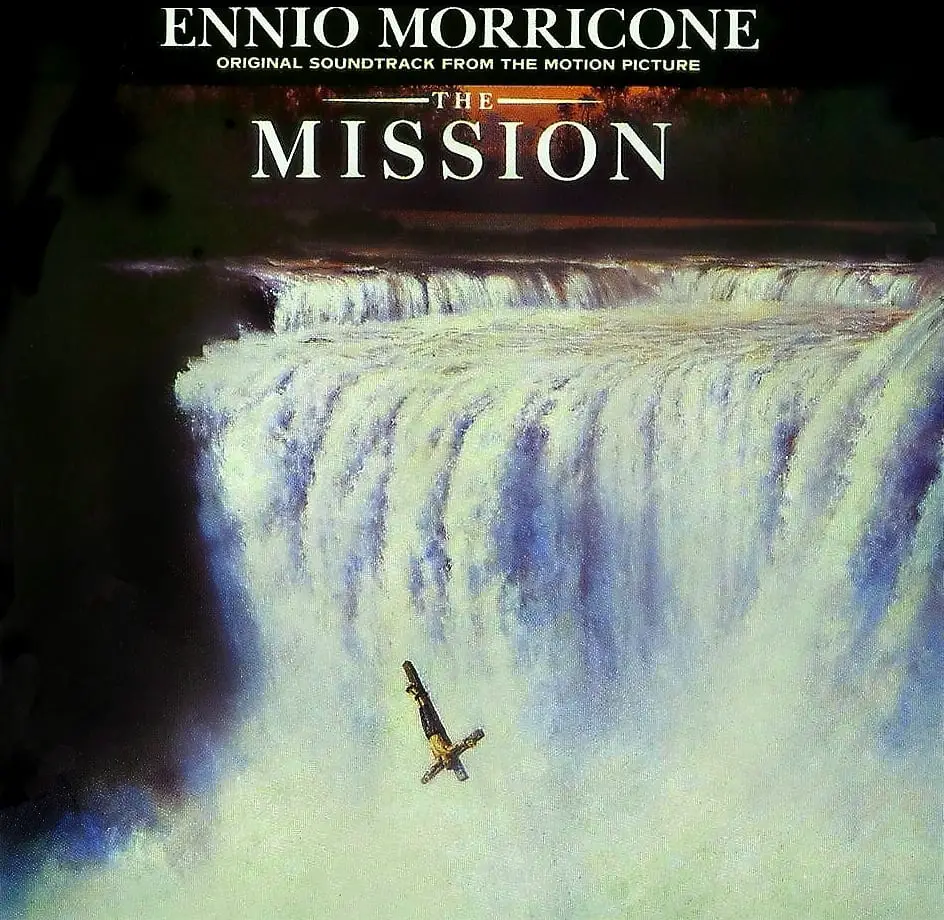

The Mission (1986)

When Morricone was asked (often) which one of his more than 400 films he has scored throughout his life was among his personal favorites, he often named his score for Roland Joffé’s 1986 film The Mission. He’s not alone in his thinking. The Mission ranks at #23 on The American Film Institute’s list of the best 25 film scores of all time. Everyone from Hans Zimmer to Vangelis has praised this work from Morricone as a major inspiration. Of course one of The Mission’s greatest admirers was Pope Francis, who just last year awarded the Gold Medal of the Pontificate to Morricone. High praise indeed. Morricone’s score for The Mission did not win the Academy Award (the award went to Herbie Hancock for ‘Round Midnight), but the score continued to move film score lovers ever since. In fact, as recently as April, Japanese violinist Lena Yokoyama performed “Gabriel’s Oboe” on the rooftop of the Maggiore hospital in Cremona, northern Italy, which she dedicated to healthcare workers and volunteers working and fighting through the coronavirus pandemic. Crying yet? Morricone often had a way of making listeners do that. Key track: “On Earth as it Is In Heaven”