…Opens the Doors to Sights You’ve Never Seen Before!

…The Medical Jungle That Doctors Don’t Talk About!

Never in Your Life Did You See Anything Like…

These lines were emblazoned upon the full- and half-sheet posters for 1963’s psychological thriller, Shock Corridor. The film’s director, Samuel Fuller, transitioned out of westerns and war films with this low-budget thriller focusing on a workaday journalist, Johnny Barett (Peter Breck), who has dreams of winning a Pulitzer Prize by committing himself to an insane asylum in order to solve the death of one of its residents, Sloan. He enlists the help of his sultry stripper girlfriend, Cathy (Constance Towers) to pretend to be his sister and charge him with attempted incest in order to get him in the doors. Once inside, he targets three specific patients who have some knowledge of Sloan’s death and who might be his killer.

The film wastes no time getting Johnny inside the joint: a few scenes of training with the help of the psychiatrist in order for Johnny’s false psychosis to come off as real as possible, and a strip/singing number by Cathy to set up an ongoing image that will continue to haunt Johnny’s dreams throughout the film. What proceeds from there is the slow dissolution of Johnny’s ego as he wagers everything—the love of a woman, his own physical safety, and, most of all, his sanity—to get the story. Notice that I did not say “the truth.” At no point does it seem as if Johnny is satisfied with the truth; he just wants a story that will make him famous and revered.

Shock Corridor thus becomes a divine punishment of human pride. Perhaps this is the reason why Fuller chose Euripides’ quote to bookmark the beginning and end of the film:

Those whom God wishes to destroy, he first makes mad.

What Johnny experiences during his trials in the “shock corridor” is something akin to a Dantean descent from Purgatorio to Inferno, yet dressed in 20th-century clothing. While it has become increasingly difficult for films to disturb a modern audience, Shock Corridor remains distressing in the images Fuller conjures to make up the hospital’s atmosphere and society. All of the negative facets of American society, post-WWII, post-Korean War and pre-Civil Rights legislation, are funneled into the corridors of this institution and released through these patients, who incarnate the long-term gaslighting that is the American dream.

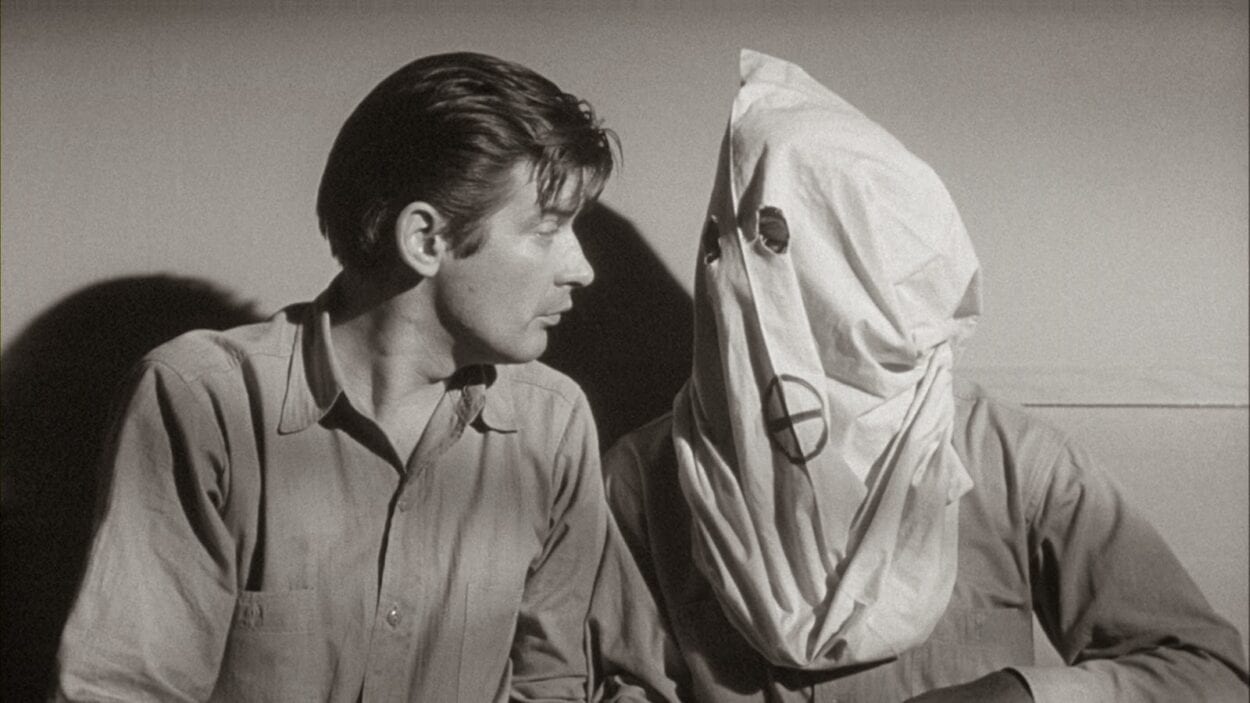

The most singular images in the film forecast our current national weather. Trent (Hari Rhodes) is a Black man in a sea of whites within the institution. He views the world through the eyes of a Klu Klux Klan leader. He explains the symbol of the KKK, he dons the white hood, and he makes an impassioned, defamatory speech to the rest of the patients, declaring that he doesn’t want Black men messing with his daughter. Hearing these words come from the mouth of a Black man is disturbing, to say the least. Later, he and some of the other patients chase after a Black attendant in the hospital and knock him to the ground. This whole time, Trent is wearing the white hood, as he thinks himself a white supremacist.

Until 2017’s Get Out, there wasn’t a mainstream term for this behavior: being in “the sunken place.” It’s a type of Stockholm Syndrome by which Trent has been so inundated with white bigotry and institutional racism that he begins to identify with his oppressors. Add in mental illness, and Trent begins to think he is his own oppressor. Trent is as deep into the sunken place as is probably possible, presaging those modern public personalities who side more often with oppressors than with their own communities (i.e. Bill Cosby and Thomas Sowell, two such examples of Black men with relatively conservative voices whom white individuals love to cite as “voices of reason”). In many ways, the characterization of Trent’s disconnection speaks to these voices that seek white approval at the expense of the very real hurt and trauma within Black communities.

Yet Trent is only one of three patients from whom Johnny seeks information; the other two, Stuart (James Best) and Boden (Gene Evans), act out their own trauma by believing they are, respectively, confederate general J.E.B. Stuart and a 6-year-old. Stuart was raised in the hatred that Trent has taken on, captured in the Korean War, and brainwashed into being a Communist, only to be re-brainwashed into being a U.S. patriot. Boden, an atomic scientist, found his split in the devastating power of the intercontinental missiles he helped build.

As we get to know these three patients by way of Johnny’s questioning, we begin to see just how shortsighted Johnny’s quest for glory really is. This is a film about national trauma, about how the things that we as a country refuse to acknowledge, confront, and redress can shape the psychological landscapes of the country’s citizenry. It makes monsters of us all. However, the film’s conclusion only puts the final thematic nail in the coffin when we come to find that the person who killed Sloan was Wilkes, one of the hospital’s caretakers. Within the scope of the film, it is someone within the institution who has perpetuated the violence, only driving home just how deep the national proclivities toward harm go.

Johnny, who has taken a journey through the nightmare worlds of American failures, has crumbled under the weight of all that he has witnessed. As a result, he is straitjacketed and shocked to the point where he can no longer trust his own mind, no longer decipher what is real from the “reality” thrust upon him by the institution he has entered, and becomes a ward of the state in more ways than one. Fuller’s vision for the film highlights a truly terrifying understanding of the pernicious lies of the American mythos, its gaslighting and underlying violence. Those who enter for the sake of glory only end up serving those they seek to find. Those who enter to seek the truth, to expose injustice, often confront the violence of those they seek to expose and sometimes don’t make it out alive.

Shock Corridor finds its footing in the rich allegorical readings that could be placed upon its narrative. While there are certainly audacious moments and imagery, it finds its actual “shock” in how it expresses the enduring forecast of the national weather. Even though it was released in 1963, this film remains a pertinent and beneficial source for contemplating current events—and what could be coming our way in the future.