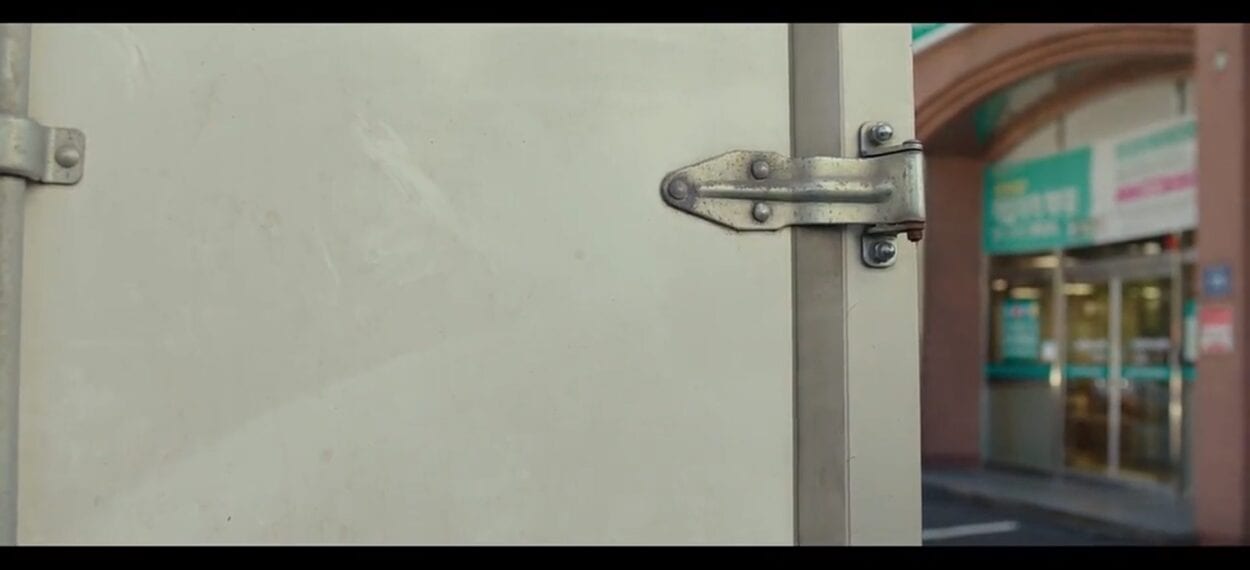

Lee Chang–dong’s Burning opens with a closed door. We wait for it to open, to obey its function, only to see a character emerge from behind it and exit via the side of the frame. Something is very wrong with this shot. The gateway that would usually permit us to enter the world of the film remains shut, and in doing so, denies the standard prophecy of its very existence: to open. The character, who we quickly learn is our protagonist (Lee Jong–su), is immediately presented at the precipice between two worlds that he will straddle and wander for the majority of the film. One is modern-day Seoul, where he meets a girl, becomes infatuated with her, and eventually, following her disappearance, decides to investigate her absence through the enigmatic man who she was last seen with. The other is the world behind the closed door. It’s an impossible space for us to comprehend, tangible only to the fictitious experience of the characters on the screen: something that is theirs and theirs alone.

In 1935, quantum physicist Erwin Schrodinger proposed a thought experiment addressing the limitations of quantum mechanics when applied to everyday objects. In simple terms, Schrodinger stated that if you placed a cat inside a sealed box with a radioactive substance that would eventually decay and kill the cat, you would not know if it was alive or dead until you opened the box. To those outside the box, therefore, the cat could exist simultaneously in two states: alive, and dead.

Burning exists, similarly, between two states, although it’s easier to think of these as states of occurrence and non–occurrence/fantasy. Emerging around a closed door that never opens imbues the denied space of the film with as much significance as the available space, and the events that transpire within it. To further parallel Schrodinger’s infamous thought experiment, there might, in fact, be a cat that is crucial to the narrative in Lee Chang–dong’s film—and, simultaneously, there might not be. To Lee Jong–su, who instigates, propels, and ultimately liberates himself from his own mystery in the film, it’s not about whether or not the cat is there or not there. It’s the possibility of the cat that matters, as an intersection between the world inside his head (the space denied to the audience) and the world we are shown on screen. There is no discernible ‘truth’ to unlocking this mystery. It’s ingrained into the system that feeds it, providing templates for fantasy with sinister potential for those who, like Jong–su, can’t get what they want from the ‘real’ world, if they even know what they want at all.

Existing quite literally on the border between two countries unified by name and name alone, Lee Jong–su can only find structure and agency within the throes of his own fantasy, and the mystery he creates for himself. Yoo Ah–in plays a character who seems to meander towards the side of the frame, constantly stooped and shuffling his way out of conversations. He finds himself drifting away in one–to–one exchanges, and even when he occupies the foreground in a scene, he is often overshadowed by the greater sense of presence afforded by other characters. Lee Jong–su’s potential slip into the realms of his own perception of what is happening, therefore, is essentially seamless: the paradox of coinciding yet seemingly disparate realities is one he is more than familiar with. He hears the North Korean propaganda broadcast all day, with the country on his porch, yet lives his life in a country with a completely different political agenda. He inherits a family property, without any real family to attach it to. Pictures adorn the walls of people we either never see, or see only at a distance.

Perhaps this is why he is able to attach such significance to the character of Haemi, and the promise of feeding her cat while she is away. In Haemi’s flat, there are a selection of what appear to be stock photos, pinned to the dresser and to a window that affords a view of an entire city, united in blocks, towers, and a certain visual identity that characterises all cities—one that is absent from Jong–su’s everyday surroundings. When she approaches him with her phone number at the beginning of the film, Lee Chang–dong’s decision to unite the two in a single long take imbues the encounter with a certain fatefulness, further spurred by the ease with which Haemi gets to know and like him with seemingly no effort on his part. Nothing consolidates this more, however, than the experience of the sunlight on his skin while the two have sex in her flat. Minutes before, she tells him of this one patch of light that appears only for a few minutes of the day, stressing its importance to her and even referring to it as “lucky”. The fact that he gets to experience this during this moment of intimacy—which, in conjunction with the fateful chance of their meeting and the apparent ease with which they’ve reached this point—means that this becomes a moment of great attribution for our protagonist. Here is a beautiful, powerful woman who is purposeful and forward with all of her endeavours, existing with a distinctive identity with no clear ties to any of the things that weigh Jong–su down, choosing to have sex with him after a chance encounter.

It’s inevitable that he reviews the experience as, potentially, something more than it is: it’s possible, even, that what we see is his projection of a perfect girl, entrenched in a fantasy of his own design. Jong–su accepts the excuse of a cat that needs to be looked after, with some part of him clearly suspecting that it is not there (“I’m not here to feed an imaginary cat, am I?”), but succumbing anyway to the game of it all, and the pretense of purpose, just for a shot of direction to his existence. There is just enough to sustain proof of the cat’s existence—a litter tray filled with poop, cat food in the flat—to dissuade the ultimate truth of its absence. Much in the same way that Haemi is both a ‘real’ girl with her own flat, personality, and goals, she is also the perfect vessel for his infatuation, and his projection of what she should mean to him after his subversion of their coincidence into something like fate. Note that when she is not around him, she is nowhere.

Consequently, Haemi herself is perhaps the most lucid example of a character who concurrently occurs and doesn’t occur in the narrative. The supposed serendipity of her encounter with Jong–su is complicated by Jeon Jong–seo’s portrayal of a character who seems acutely aware of the fact that she is being played, and succumbs wholeheartedly to that performance. Stepping away from Lee Jong–su’s perspective, it’s clear to see that they don’t just bump into each other—she’s waiting for him, ready with her phone number, to play her role in the film. The effortlessness of their union and her decision to have sex with him also makes little sense when viewed from this detached perspective. Throughout Burning, it becomes evident that Lee Jong–su not only fails to engage with her properly on any level, but genuinely seems to have derision towards some of the things she says and the ways in which she expresses herself. Later scenes, where they are part of a large group of people, see him and Ben sharing meaningful looks and yawns while she talks over other characters and essentially steals the show—which infuriates Jong–su and fuels his anger towards Ben while reminding him that he, too, doesn’t particularly care about Haemi either.

From their first full conversation in the restaurant, it’s clear that Haemi’s sole purpose within the film is to impress meaning upon a narrative centred around the mystery of her existence, and to provide the catalyst for Jong–su’s real obsession with Ben (which we will return to shortly). To say that she stokes the “burning” of the film would be an understatement. In this conversation, she essentially outlines the blurred lines between occurrence and non–occurrence that will characterise the events of the film. Holding a tangerine between her fingers, she declares that “she’s learning pantomime these days”, and, focusing on the fruit, that the trick is to not forget that there is a tangerine, but to forget that there isn’t one. To indulge Burning fully is to forget the boundary between films and reality, dream–states and waking–states, or whether the cat is imaginary or real. Much in the same way as she plants memories into Jong–su’s head that may or may not have happened, she plants the idea of a cat that needs to be fed as the catalyst (sorry) to the prevailing mystery of her existence: the eternal ideal of the woman that wants you.

Implying, however, that Haemi is subjugated by the way that Jong–su chooses to see her would also be a mistake. It’s arguable that she’s the only truly empowered character in the film, playfully toeing the lines between the dusk and the morning, never giving herself over to either Jong–su or Ben and eventually slipping away before the poison starts to seep in. She repeatedly claims throughout the first half of the film that she wants “to disappear”, to succumb to her “great hunger” and, implicitly, to escape the cloying grasp of the men that feed the fantasy of her—and she does. Prior to the sunset dance (which, on a side–note, is one of the most exquisite, powerful scenes I’ve ever witnessed in a film), she slowly seems to be attuning more to the natural world than the artifice of the film through Jong–su’s eyes. When she goes to Africa, he finds himself masturbating in her flat, using the patch of sunlight as a means of summoning the warmth of her. When she arrives at his family home, she just appears with next to no warning. These are signifiers of her attunement to that which is ephemeral and outside of Jong–su’s control, if not necessarily his wonder.

It all comes to a head the moment she pulls her top off, takes the camera with her to the sunset, and initiates the “great hunger” dance. Lee Chang–dong pushes the camera past the two men, pushing them briefly to the denied space that they emerged from, and focuses entirely on Haemi, who stares directly at the camera as the breeze ruffles the fields and the light slips into murkiness. It’s important to note exactly where she stands. Exposing herself to North Korea, “just over there”, and dancing beneath the South Korean flag, she traverses the border between two worlds with a command and authority that will serve as the final nail in the coffin for consolidating Jong–su’s fantasy. Here is the proof that his lack of attachment to any kind of political, geographical, or familial identity can, in its own way, be worn as an identity in and of itself. It can be a position of power, one that he will so long to occupy for himself and one where he feels he will finally be able to attain her. This scene, which precipitates her sudden disappearance, establishes the middle space between dead and alive that she will occupy from thereon in, sealing the box with her and the cat inside. It also marks the transition from believing that the film is about Haemi to realising that the film is, ultimately, about Ben.

When Haemi goes to sleep immediately after, Ben and Jong–su sit on his porch as the blue of dusk slowly evaporates into the grey of the night. Jong–su opens up to Ben about one of his most painful memories: being forced to burn his mother’s clothes after she left his father. Ben, in response, tells Jong–su that, every two months or so, he burns down greenhouses, for no reason other than the sheer “base thrill” of it. He hints towards burning one that is “very near” to where they are sitting in that moment.

The dynamic between Lee Jong–su and Ben is a fascinating one. At first, it appears that Jong–su merely despises Ben, who he sees as one of the many “Gatsby’s” living in South Korea: young, rich, nihilistic and without principle. The jealousy that he feels initially seems to revolve around Haemi’s apparent preference of Ben over him, but, following her absence, it evolves into something far more pertinent and dangerous. Jong–su transitions from wanting to outshine Ben, to wanting to be like Ben, to wanting to be Ben. Here is a man who, by his own words, is “here, and there…..in Africa and Seoul….at the same time”. Here is a man who is able to indirectly transform the traumatic associations that Jong–su has with the act of burning something to the ground into something cathartic and metamorphic, cleansing himself of all that he has collected in the weeks leading up to the burning and finding himself reborn.

Like Haemi, Ben thrives in absence; with no moral compass and no surname to secure him to a troubled legacy, he is the ultimate template for the modern man, and just as much of an anomalous duplicity as the girl that brought them together. He also holds total authority over all of their encounters: Jong–su almost never finds him for himself, but is found by Ben, who always has the upper hand in the mystery of whether or not he has killed/kidnapped Haemi.

All this together makes Ben not just a confounding figure for our protagonist, but a thoroughly desirable template for all that he could be if he knew how to subvert the concept of burning into something that resembles rebirth, rather than destruction. In the only explicit dream sequence in the film, Jong–su remembers the night of the fire, watching his mother’s clothes go up in flames. Here, he is smiling with delight. Whether this was his reaction or whether this was what he wanted to feel is indistinguishable: what matters is that this is the ultimate evocation of the Ben inside of him, and the future potential for soullessness and rebirth that might await him should he find a way to consume this figure for himself.

Note, also, that he is never quite the antithesis of Ben in the way that the film might make you believe. He is not kind, or guided by the principles of right and wrong. He is not a family man, and he does not truly care for Haemi or the people that knew her. Ben is merely symbolic of the opportunity to turn these flaws into something powerful, something appreciated, to the point where they are no longer flaws but attributes of attraction.

It’s important to note that, later, when Jong–su is investigating Ben’s flat for traces of Haemi, the cat in his house doesn’t just appear but essentially materialises within the frame, emerging similarly from the side of the frame to Jong–su without introduction or revelation. Just like our protagonist, we have no idea of what Haemi’s cat looks like, only that it has an unusual name. When the cat responds to this name (Boil), Jong-su sees it as the ultimate proof of Ben’s complicity in her disappearance—despite the fact that, in the previous scenes in her flat, Boil never responded to being called. The possibility of the cat is proven simply by the existence of the only other cat we see in the film, and even this is realised solely through Ben’s possession of it.

This is the final straw for Jong–su, not only in justifying his eventual murder of Ben but in embellishing him as the figure who can so easily attain that which is, in a sense, impossible to claim. As mentioned earlier, Jong–su always suspected and perhaps even knew that there was no cat to begin with. Yet here is Ben with a cat that he claims to be his, responding to Boil and following the principle of “just enough” that pushes him to the edge. There’s just enough to prove that Haemi disappeared under mysterious circumstances. There’s just enough to suggest that Haemi was real in the way that she proposed to be real, and the memories she gave him held credence. There’s just enough in Ben’s flat to suggest that he’s killed her, and there’s just enough evidence in his cat’s response to the name Boil to confirm this. This principle, however, can just as easily be subverted to reinforce the total fabrication of not only this theory, but the existence of the characters themselves, or at least the way we see them as an audience. The cat is both Boil and not Boil.

The proficiency with which Ben is able to navigate and control any and every situation that Jong–su attempts to create between the two of them can only be thwarted by the film’s decision to submit entirely to the state of non–occurrence at the end. Although it still isn’t made abundantly clear, it seems likely that the last ten minutes of the film represents the “break” between the two opposing states that have empowered the characters that Jong–su has been chasing. Here, we see our protagonist, having seemingly moved into Haemi’s apartment, writing for the first time in the film, before cutting away to small vignettes of Ben going about his daily rituals. This will be the first and only time we see Ben as detached from Jong–su, and this alone represents a seismic shift in control, separating Ben from his enigmatic, commanding persona and humanising him to an extent.

The following scenes, therefore, can be read as a product of ultimate fantasy. When Jong–su stabs Ben in his car, shuffles out of his clothes, and burns them with him in the vehicle, the camera slowly starts to pull away, not stopping until it meets the credits. Naked and magnetised by the pull of the camera, he climbs into his car and drives away, towards the fleeing lens, with his face hidden by the rain on the windshield.

For all the failed divination, red herrings, and transmissions of other people’s wishes in the film, it finally seems as though Jong–su has found something to write about and create for himself. Writing in the space where he first ascribed this mystery to himself, he constructs its natural destination: the consumption of the man that embodies everything he despises and everything he wants to be. It’s a perfect dream: there’s even an army truck that passes directly next to the scene of the murder without stopping. This inclusion not only affirms the potential for the fabrication of this murder, but also pertains towards a world full of Ben’s who simply do not care about the evisceration of another human soul.

It’s a world we’ve seen for the last hour and a half, completely unfazed by Haemi’s disappearance and immune to the suffering of others, that Jong–su wholeheartedly submits to, using the flames of Ben’s decimation to find himself naked, reborn, and without a face. He finds a way to make that which is destructive, traumatic, and loaded with meaning, into a conduit for his own resurrection as just another ghostly figure, driving past horror in the same way that everyone else is able to do. Burning fades to black, slowly, and we must return once again to the closed door.

Was that actually Jong–su, murdering that man, driving away? Yes and no. He was there and he wasn’t—doing it, and creating the doing somewhere else. To assume that this final vindication was the first realised invention of Lee Jong–su certainly holds merit, but it almost doesn’t matter. The difference between the doing and the inventing has, by this point, been totally eradicated. We are what we see ourselves as, and the same applies to how we project this onto others. Throughout Burning, Jong–su doggedly chases ghosts and ideals of people that may or may not exist with completely different names and faces, with no way of us knowing where they end and where his projection of them begins. They’re in Schrodinger’s sealed box, and the central mystery of the film is much like that radioactive substance, destined to decay but, ultimately, always alive and positioned towards destruction.

The toxicity of Jong–su’s male–centric fantasy, centred around his own insecurities and weaknesses, will always remain. There’s no cut to black, only a fade on a faceless man, circumventing concepts of there and not there, closed and open, created and real. The door remains closed, with faceless men walking around it. The box is sealed tighter, and slipped under the bed with the litter tray, while Lee Jong–su occurs and doesn’t occur in the stories he writes for himself.