Stanley Kubrick: an icon of modern cinema. Kubrick is a household name with 45 awards and 62 nominations to his work, including an Academy Award and two BAFTAs. His legacy will always be found in his horror works, and in his most popular movie: 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). However, Kubrick created cinema across a variety of genres including politics, satire, dark comedy, psychological conflict, and war. Today I want to discuss the extent of his legacy, as well as the themes that stand out across his vast portfolio, taking you through the recurring motifs, genres, character tropes, and controversies throughout Kubrick’s cinematic career, as well as appreciating his breadth and versatility as an artist. There will be spoilers for the majority of Kubrick’s films ahead.

As most of his films were adaptations of popular print stories, this could account for some of the versatility. Working with already well–known stories can make even those outside your usual scope feel more familiar and therefore easier to work on. His highest–grossing films, adjusted for inflation, are 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange (1971), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999). All five of these films captivated audiences, but do not share much outside of this.

Perhaps you know Kubrick as ‘the man who does horror’, or ‘the man who did A Space Odyssey’, but Kubrick is much more than one definition. His films cover a plethora of genres and experiences, consistent in neither violence, aesthetic, nor social commentary. His legacy is a complex one, and there are many different interpretations of some of his more controversial works.

But let us wind it back a little bit. Kubrick’s feature–length film career began in 1953 with Fear and Desire. This film is just over an hour long, and was received well by critics—although it’s lack of success in the box office did not reflect this. As Kubrick had been a photographer for some time before creating this film, it feels very arty, and you can tell he is drawing influence from his time as a photographer. The camera style is well thought out, and there is a fair emphasis on backgrounds and scenery. The film itself is an anti–war commentary, although it is not about any war in particular. At the time of its release, Kubrick was unknown in the movie world.

It was not until the success of Lolita (1962), that Kubrick really entered the spotlight as a recognised auteur. Once Kubrick became more well–known after directing such a controversial film, his style started to branch out and shape into what we see today.

Character Tropes

Kubrick creates some eccentric characters for us to see, and there are themes that recur in his portrayals. Common sights are villains who are beyond redemption, damsels in distress, and characters who just cannot seem to stay afloat—be it mentally or physically. I will take a look at two types of character that frequently pop up throughout Kubrick’s portfolio, and discuss what makes them unique to Kubrick.

One recurring character trope in Kubrick films is the weak, female supporting character. From Wendy (Shelley Duvall) in The Shining to Mrs. Alexander (Adrienne Corri) in A Clockwork Orange, and all the roles in between (Gloria in Killer’s Kiss, and the many women in Eyes Wide Shut), Kubrick takes away women’s intelligence and creates shallow, air–headed characters. This has been widely criticised by many, including some original writers of Kubrick works—but we will touch on this later. Weak women seem to be the most commonly occurring type of character in Kubrick’s work.

For the most part, female characters are support for male protagonists and they are usually in the background. His only film with prominent female characters as a focus is Eyes Wide Shut, which depicts them spending most of their time taking their clothes off and making unintelligent choices.

In fact, almost all of Kubrick’s female characters are either there to scream and be scared, be rescued, or show their bodies. If they are not young and attractive they are elderly, bitter, and powerless. There are no strong female characters to be seen, and those that are present are used as props to the male protagonist’s tales. This is a critique that was brought to the fore of discussion about Kubrick’s works when Stephen King spoke out against his vision of Wendy in The Shining. King, in an interview with the BBC, called Kubrick out for his portrayal of women, bringing attention to the lack of strong female characters. You can almost tell whether or not a film is Kubrick’s by its presence (or lack thereof) of women roles.

Another character trope that we see a lot is characters who are suffering from internal conflict who end up spiralling into mental health episodes. The prime example of this is Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) in The Shining. Jack is a writer who has taken a job keeping an eye on a hotel while it is closed for the winter months. He takes his wife and child and the situation seems to suit everybody—Jack has space to write, Wendy has peace and quiet, and their son Danny (Danny Lloyd) has all the room to play he could possibly want.

However, things take a turn when Jack begins to descend into madness. His decline is for all to see, as he begins to furiously type the same sentence over and over again, and frighten his son and his wife. Kubrick shows us how good he is at directing scenes showing us the mental deterioration of a character. The acting is also outstanding, but you can tell each scene is incredibly well planned and meticulously executed.

Another character who faces extreme disconnection with reality is Alex (Malcolm McDowell) from A Clockwork Orange. Alex is a violent criminal, and even after he is apprehended and ‘rehabilitated’, it is clear that he struggles to connect with those around him. A free man once more, he continues to sink further into a detrimental mental space until he attempts suicide. The film ends with Alex still having violent tendencies, and remaining delirious about the society he is in. The original novel ends with Alex successfully being rehabilitated, but the film is much more negative, and arguably much more realistic, about where Alex ends up.

Burgess himself, the original writer of A Clockwork Orange, commented on the omission of the final part of the story, which details Alex’s redemption. While this is more to do with the press in the United States releasing copies of the book also omitting this final chapter, it was still a stylistic choice from Kubrick. He chose to focus on the darkness and violence of Alex than look at how he may have been rehabilitated.

There are other films with similar characters—Eyes Wide Shut, Dr Strangelove, and Full Metal Jacket all follow characters who are experiencing mental conflict—but the character I really want to discuss is the one that does this a little differently. HAL 9000 (voiced by Douglas Rain) is a character from 2001: A Space Odyssey. HAL is an AI robot whose job it is to make sure the astronauts are safe, and to assist them in whatever ways they need.

However, things go south when HAL starts to try and kill the astronauts. It is one thing to feasibly depict a person going mad, but to characterise the descent of a robot into madness is something else entirely. We watch in horror as we begin to realise what is happening, and the sabotages from HAL get more and more intense. Kubrick is not only excellent at showing us how humans descend into sketchy mental space, but he manages to use this trope on a robot too. This is testament to his creativity and skill. We all view HAL as just another character: once he has motives and desires like we do we forget he is not one of us.

When HAL speaks he speaks slowly and with purpose. He sounds frightening and calculated. To be able to direct a character to both sound this way and be in internal decline demonstrates a keenness for this type of character. HAL is probably one of Kubrick’s most popular and interesting characters of all time. Kubrick has an innate sense of humanity reflected through his entire collection of work. This knowledge of how humans tick is what makes his villains so unique. Few could write the descent into madness with quite the same horror as Kubrick.

It seems as though he is drawn to characters who are facing a psychological plight. Perhaps it is because this is where the interesting stories are, or perhaps it is because he personally feels connected to characters who are struggling, in the way that many of us do when we see them in film. Whatever it is, Kubrick has a talent for showing us human nature in all its gritty truth.

Kubrick and Violence

Violence is a staple of Kubrick movies, and something he is well–known for. Kubrick himself states in an interview with the New York Times that it is “the true nature of man” to be “savage”. More of that human nature grit, beyond the psychological, can be found in Kubrick’s attitude towards including violence in his movies. I want to break down this violence and establish how the different elements weave together to create Kubrick’s reputation.

Gore

Some of this violence comes to us in the form of your typical gore. Films such as Killer’s Kiss (1955), Spartacus (1960), and The Killing (1956) all feature standard violence—that is, mild gore. When Kubrick used this type of violence it was always to create an atmosphere, and it set him up to go further in later work.

The Killing is essentially about a conman at the end of his career wanting to carry out one final robbery. It is a film noir, and a little bit eerie. It features multiple shootings, all shown in a fairly typical way. The violence is not shocking but it is present. The story itself is very well executed, and the monochrome gives it a feel of timelessness and beauty. It is a comment by Kubrick on the nature of man, setting the stage for his later films which also comment on the negatives of human nature.

Similarly, Killer’s Kiss gives us some violence. Another noir, Killer’s Kiss was Kubrick’s second feature film, and, like his first, starred Frank Silvera. It is about a boxer and his neighbour, Gloria (Irene Kane). Although the main character’s profession is boxing, which is portrayed tamely enough, but the film does give us a murder in an alleyway. There is also a rather bizarre scene where two men are fighting to the death in a mannequin storage room.

It’s a very Kubrick scene—has his hallmark humour and darkly comedic tone, but it is also unsettling in a way that is difficult to describe. The scene involves the plastic, lifeless bodies of the mannequins flying all over the place, giving a darker atmosphere to a scene already focused on an axe duel. All of the sounds for this movie were added after the fact because Kubrick was unhappy with the results from the sound editor, which speaks volumes to his commitment for everything in his art to be ‘just so’. These scenes were all deliberate and used to create exactly the unsettling effect he wanted.

Spartacus shows us some scenes of violence, but here the violence is used as a plot device. There are some intense battle scenes and also a suicide, but this is kept off–screen. The film is about a rebellious slave who wants freedom. After being bought by a man who owns a gladiator school, Spartacus (Kirk Douglas) leads a revolt. Like The Killing, the film shows some of Kubrick’s disdain towards human nature. This theme emerged very early on in his work and continued throughout, resurfacing in later works such as A Clockwork Orange and Full Metal Jacket.

Barry Lyndon (1975) is a final example of a film with this type of moderate violence. This film is a personal favourite of mine, and the story often reminds me a little of the backstory of Jay Gatsby. We are treated to multiple duels in this film, and, although it is a drama, the film is action–packed and the story is fantastic. Kubrick wrote the screenplay for this film himself.

Lyndon (Ryan O’Neal) becomes a soldier after feeling dissatisfied with his life, and he aims to raise his social standing after the war. He indeed goes on to marry a rich woman and settles in England when it is over. Originally from Ireland, Lyndon is unaccustomed to his new way of life and it is his mother who tells him that without a title himself, he will lose his wife’s riches should she die.

This sets in motion a chain of events leading to Lyndon trying even harder to integrate himself into his new life. However, things inevitably go wrong for him. After he falls out with his stepson and his own son is paralysed by a riding accident, things are looking bleak once more for Lyndon. Eventually, he is offered money by the father of his wife to return to Ireland and never travel to England again. He reluctantly accepts this.

The whole film shows us how the pursuit of wealth and status are not noble, and that obtaining these things will not make us happy. Kubrick is again warning us about the darkness in human nature, this time focusing on greed. It’s a well–executed tale and the message is very humbling.

All in all, run of the mill. Gore violence is not something Kubrick focuses on. The kind of violence that Kubrick uses more often is much harsher, darker violence. These stories here are more about humanity and the flaws we all share than about an expression of violence. However, looking at these older works, the theme is definitely present from the very beginning.

Sexual Violence

There cannot be a comprehensive discussion about Kubrick’s works without discussing female exploitation. Lolita (1962) was Kubrick’s break–out film, depicting a middle–aged, male school teacher who repeatedly rapes a young girl (although this is not shown on–screen) because she was ‘sexually provocative’. Humbert (James Mason) waits on Lolita (Sue Lyon) hand and foot, with the expectation that her side of the bargain was to provide him with sexual favours.

In one scene, he says to her, “whenever you want something I buy it for you automatically, I take you to concerts, to museums, to movies. I do all the housework. Who does the tidying up? I do!”. Instead of these being seen as normal things for a guardian to do for a child, he uses them as reasons for her to be grateful and feel that she owes him. Humbert also shows jealousy when Lolita spends time with boys her own age and forbids her from dating them.

It is a deeply disturbing story, there is no doubt about that, and not least because of some of the changes Kubrick made to the original story. The teenage girl and title character was portrayed to be a seductive, classic beauty, one whom the focal character Humbert ‘could not help’ but find himself inappropriately drawn towards. It was Lolita that initially brought Kubrick to fame, and to this day it remains his most controversial work. It is a simplified version of the book by the same name. If Kubrick picked this story looking for attention, he certainly got it.

When making Lolita, Kubrick did not use the screenplay written by the novel’s author (Vladimir Nabokov), instead opting to write his own script. This directing choice, while down to his artistic license, created differences between the original story and the one we see unfold on our screens. The two most notable differences are the change in Lolita’s age (raised from 12 to 14, to adhere to regulations), and Kubrick leaving out almost all scenes from the book where Humbert catches sight of Lolita’s discomfort and sadness. The latter omission feeds more darkness into an already dingy tale.

The film has been widely criticised for downplaying the exploitative and paedophillic nature of the focus relationship, and for creating a romanticised vision of the abuse. Most synopses of this film still list it as a ‘classic love story’, something that is a testament to the way the film was told by Kubrick.

Despite the shooting of Clare Quilty (Peter Sellers) at the very end of the film and a suicide scene, the violence here is predominantly sexual in nature. While there are no explicit scenes of graphic or sexual nature throughout the film (the actress playing Lolita was herself just 14), there are scenes of strongly implied sexual intent, sexual tension, and engaging in vastly inappropriate actions with a minor. This itself alludes not only to statutory rape, but also intentional grooming of a child, and exploitation by a person in power.

It is my personal opinion that grooming and implied rape of a child is enough to consider this a sexually violent film. Even without suggestive scenes such as those the book also tried to shy away from, the entire premise of the story is based around the sexual relationship of a middle–aged man with a child.

Eyes Wide Shut moves away from overt sexual violence, and more into sexual exploitation territory. This film gives us one of the few female focal performances in Kubrick’s work, but the role of the focal female characters seems to be to get naked and be silly. It is the epitome of male–gaze cinema. There is no holding back on sexuality here, the film features full–frontal nudity, numerous sex scenes—including an orgy—implied teenage prostitution, and could easily be described as soft–porn. The women characters are all weak and obsessed with romance and sex. There are no complexities to them and it is so clear that they have been written by men.

It is possible that Kubrick was using this film to highlight how women are seen by society at large, rather than the film is a projection of his own internalised misogyny. However, when you evaluate his works as a whole, women are never presented in any other way, so it is difficult to imagine that Kubrick chose this project purely to make a stand on their behalf. The women in this film are treated as objects, and they don’t seem to have any individuality at all.

Throughout Eyes Wide Shut the female body is used excessively for nudity, never as a plot device. Unlike in A Clockwork Orange where the nudity is necessary to give us an unflinching story, it seems to exist purely for the eyes of the viewer. This calls into question exactly who this film is aimed at. It seems to me that, unless you are particularly interested in seeing women’s bodies, this film would not appeal to you. The storyline is very weak—marketed as an erotic, psychological thriller. Eyes Wide Shut really only serves those who are more interested in exploitative nudity than a good story.

In Killer’s Kiss, Gloria’s boss is seen repeatedly trying to kiss her, despite her objections. He later attacks her, and Vincent, the main character, has to come and save her. This is another example of a weak female character, as well as adding this film to the list of those depicting sexual violence against women.

Finally, we cannot discuss sexual violence in Kubrick films without ending on A Clockwork Orange. This film is notorious for its unflinching depiction of multiple rapes and sexual assaults, as well as its fair share of regular gore. Alex (Malcolm McDowell) is the ringleader of a gang who terrorise their area, thinking nothing of assaulting people, especially women. In the same way that mediocre gore was not enough for Kubrick’s expression of violence on–screen, Alex and his droogs are not content with petty crime.

When Alex and his Droogs rape the wife of Mr. Alexander, a local writer, early on in the film There are extended shots both of the rape itself, and the men exposing Mrs. Alexander’s body in front of him as he is helpless. The film also contains multiple beatings, as well as intimidation and further sexual assaults against women, a common theme in Kubrick’s works.

Military Violence

As numerous of Kubrick’s feature films take place in war–time settings, military violence is a key element of the violence we see in his films. Kubrick would struggle to be considered a master of violence without the violence in his military–themed movies.

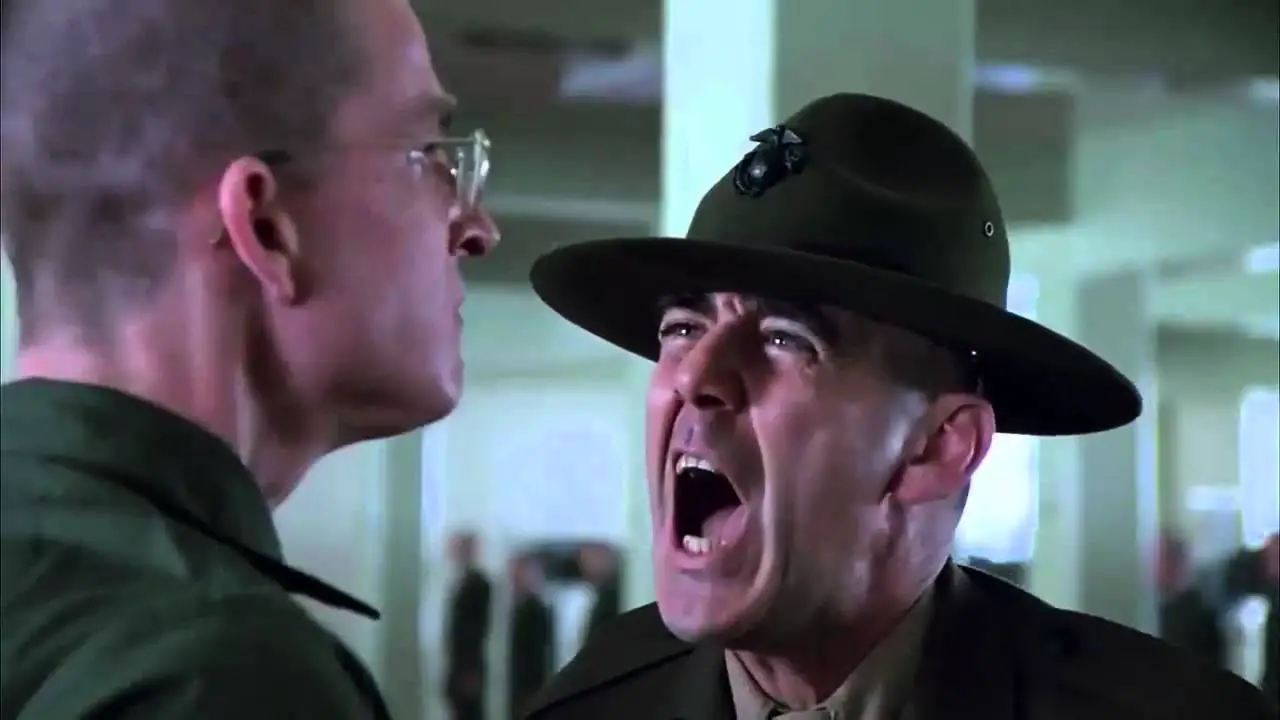

Fear and Desire, Full Metal Jacket, and Paths of Glory (1957), and Dr. Strangelove (1963), all follow stories that take place either during a war or about war. Kubrick’s most popular war film is Full Metal Jacket, which grossed $46,375,676 in the American box office. Each of these films portrays violence differently, suggesting it is a theme Kubrick enjoyed exploring more so than a theme he was comfortable in and had a particular style with. This being said, both Fear and Desire, Kubrick’s first film, and Paths of Glory are very against wars in their content.

Dr. Strangelove, although satirically about the Cold War, is not really a war film under the typical definition. There are some battle scenes, as well as explosions, but the film is more political than military and is framed as a comedy more than a tragedy. It is still a disturbing film, but I don’t see it this way because of its approach to violence. There is an off–screen suicide, another thing common in Kubrick films, but this is not graphic.

This film is Kubrick’s only true comedy. Many find dark humour in most of his works, but this one is the stand-out for making audiences laugh. Every twist has a funny punchline, and Kubrick displays not only his knowledge of the human psyche but also his ability to tickle its amusement.

Full Metal Jacket, however, is an incredibly violent film set in wartime Vietnam. There are many graphic scenes depicting war deaths, suicide, and physical violence between soldiers. Many scenes, the suicide especially, are particularly harrowing because of the graphic nature in which they are shown. Kubrick is not holding back when he shows us what wartime violence can be.

Paths of Glory (1957) is based on a novel by Humphrey Cobb of the same name. It follows an anti–war narrative and is more abstract in its storytelling than Full Metal Jacket, which simply depicts the terrors of war as they are (or as Kubrick sees them). We see many characters rejecting the requirement of them to commit violence. This gives the film a very anti–military violence feel, and you can sense through the art a disdain for real–life violence.

The way Kubrick dishes out violent scenes sparingly and unusually shies away from more graphic violence, gives viewers a sense that he is uncomfortable with the terrors of war from this perspective. Because we know him to be confident showing violence in other films, this choice feels deliberate. We are supposed to focus on the sadness of war, not the action.

It has a certain level of violence, as will any war film, but it is more of a social commentary. Besides one scene where a man is executed by firing squad, Kubrick largely keeps the violence quick, preferring to focus on war as a negative rather than the glamorous pursuit of injury we see in some, less well–done films. In this film violence isn’t the aim, more so a necessary method within its madness. Kubrick told this story in order to shine a spotlight on unnecessary wars, human nature, and the plight of soldiers.

Visual Violence

When I say visual violence, what I mean is violence that comes in the form of imagery, not violence as an action. The idea that violence doesn’t always have to be something being done to someone, but can also be imagery that provokes the same reactions as aggression. The best example of this in Kubrick’s work is The Shining. Although not Kubrick’s most famous film, it is certainly well–known. There are some violent scenes, but nothing particularly graphic. Instead, what we get more of are images that are visually disturbing, but not necessarily violent in and of themselves.

The most poignant example of this within The Shining, is the woman, Lorainne Massey (Lia Beldam), that Jack (Jack Nicholson) finds in the bathroom of one of the hotel rooms (number 217). When he finds her, she is nude and appears to be bathing. However, when he begins to have physical contact with her she begins to disintegrate and rot. This gives us a minor jump scare as her moldy body is revealed to us in the mirror behind her, and the focus of the camera on her decaying body is almost nauseating.

While this scene does not show physical violence between characters, or even self–inflicted violence, there is something very violent about seeing the woman’s body the way that it is shown. The scene takes its time, and the characters move slowly, accompanied by a score that builds into a crescendo that assures us something is up before we even realise what is happening. The image is just as haunting as images of physical injury or gore.

It’s worth also noting that this scene draws parallels to Kubrick’s use of female characters in general. Before Massey’s body begins to rot, we see a prolonged scene of her walking towards Jack, and holding him. She is fully nude throughout her role, and there is a lot of focus on her body as beautiful before the horror begins. Her entire role is to be beautiful and then be destroyed. She is a plot device for Jack’s narrative.

Violence Behind the Camera

Many Kubrick films are noted for their violent imagery and intent. We know that Kubrick did explore the horror genre multiple times and that this is something that will live on in his legacy. But how did this passion to show violence translate off–screen?

The Shining is perhaps Kubrick’s more widely–recognised horror. And it seems he took the genre to heart, creating a hostile environment on set as well as on camera. It has been well–documented that Shelley Duvall suffered from a mental health crisis after the intensity of shooting with Kubrick during The Shining. With the film rated 18, but little graphic gore violence on–screen, it sounds like there might have been more horror on set than we ever saw in the finished movie. Shelley Duvall was reportedly yelled at, degraded, and left traumatised after her experience shooting the movie. Despite her vast efforts, she did not receive much credit for her role, with Kubrick and Nicholson getting the bulk of the critical praise.

The Wendy we see is not the most rounded female character. She is largely there to reassure us that this is, indeed, a horror. She screams, she is weak, and she is not very intelligent. King himself spoke out after the release of The Shining to express his critique and displeasure at how the film turned out. He had originally written Wendy as an intelligent woman, and an equal to her husband. This is not what he saw reflected in the movie, and he branded Kubrick a misogynist.

Kubrick, despite being Duvall’s biggest champion in trying to get her cast for the role,was very critical of her on set. During the 13 months of filming, Duvall’s mental health declined significantly, and she fell off the radar shortly after 1980. During filming, Duvall was often kept isolated from other cast and crew who were told to ignore her, and the crying in the famous baseball scene is genuine. Because of how many takes Kubrick shot of this scene it gained a Guinness World Record for the most takes of any dialogue scene in the history of cinema (there were 127). So, it looks as if Kubrick’s commitment to the horror genre could have been to a fault.

In the years after his death, many referred to him as having been a recluse. However, members of his family, including his wife, Christiane, have spoken out to say that this is not the case, and he was instead committed to his craft. But, knowing what we now know about his sets, it’s easy to wonder if he was committed to his work itself, or to the power and adrenaline he felt when he was shooting.

2001: A Space Odyssey

2001: A Space Odyssey is Kubrick’s most popular film of all time. As Kubrick’s only dabble in the sci–fi genre, it does not fit with any of the categories previously discussed. It is also Kubrick’s only film to receive a certificate ‘U’ (by the British Board of Film Classification). It being his most popular work, we can see that Kubrick is capable of exceptional storytelling without the inclusion of excessive violence, sex, and other adult themes. It is this film that cemented him as the incredibly talented man he was.

The story follows scientists investigating what life would be like on other planets, and the fallout after HAL, a computer system that behaves like a person, begins to malfunction. Instead of protecting the astronauts, it begins to try and destroy them. As Kubrick’s only film to explore the sci–fi genre, it clarified his versatility and commitment to trying new ideas. The film explores human life going beyond our planet as we look toward the future where we may face extinction. It gives us hope about the future of our species and lets us believe that there may be more for us out there. For many people who weren’t taken in by Lolita, this was their introduction to Kubrick as the film quickly rose to fame after its release.

Social Commentary

Similar to the variety we have in genre, there is also a lot of conflicting social commentary if you look at the broad themes across Kubrick’s entire catalogue. His career spanned almost 50 years, and of course, a person changes over such a time frame, but it is still interesting to see. We go from anti–war themes (Paths of Glory) to aggressive violence (A Clockwork Orange and Full Metal Jacket), from protecting women (Killer’s Kiss) to abusing them (Lolita), and from seeing no women at all, save for some small scenes featuring prostitutes (Full Metal Jacket), to seeing them focally and naked (Eyes Wide Shut). These clashes make Kubrick’s work interesting. He has his own style, but the changes between each piece mean you cannot get bored.

This lack of consistency in his storytelling shows a superb grasp of perspectives, as well as a skill and attention to detail that is rare. In order to create films displaying such juxtaposed materials, Kubrick must have been incredibly well–versed in playing the devil’s advocate within his own writing.

However, there are some things that Kubrick’s commentary remains consistent on. One—that man is naturally flawed and often evil; two—that war is a byproduct of this, and we create violence and destruction only to fall on our knees when it comes for us; and three—that the human psyche is not capable of comprehending some of the most heinous acts of our species. It is on these three assumptions that Kubrick displays much of his work into human nature, and there are reflections of them in each of his works.

Controversies

Kubrick’s career was littered with controversy, and no topic more discussed than the paedophilic scenes from Lolita. I wonder if we would have found this film as acceptable if it had not been a novel first. Lolita is, to this day, widely criticised within many circles, and of course, the message it was trying to send out is dubious.

Since his death, there has been more attention surrounding the treatment of Shelley Duvall on set of The Shining, with many speculating that, while she was feeling the strain of being an actress before she began work on the 1980 horror, it may have been Kubrick’s treatment on set which caused her mental health to spiral downwards so drastically.

We have also seen backlash from audiences about the motives behind filming Eyes Wide Shut. Many critics and viewers alike see it more as a perverted and unnecessarily pornographic film than as a compelling tale. The film’s relative success is likely down to the proximity of its release to Kubrick’s death, more so than for its content and merit. It was hyped up a lot before its release, after the death of Kubrick. However, once audiences started viewing it the hype went down rapidly. It is now regarded as something of a flop, not least for its lack of substance in its female characters. There are some who hold the film in high regard, but it seems there are more who don’t.

As well as his lack of meaningful female characters, Kubrick films are not very ethnically diverse. While this is not unique to Kubrick, it is certainly noticeable. There are very few characters in his films who are not white, and, indeed, in The Shining the only death to actually occur is that of Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers). His character shares Danny’s (Danny Lloyd) powers and tries to save the family when they get into trouble at the hotel. Halloran is also referred to by a racial slur, which does appear in the book but could easily have been taken out. While there is not much discussion about this in the media, it is something I couldn’t help but pick up on when evaluating the aggregate of Kubrick’s works as a whole.

Despite these controversies though, Kubrick remains a household name. He is loved for the art that he gave the world, and for the legacy he leaves behind.

Kubrick’s Legacy

Kubrick was a versatile, committed, and memorable creator for more than just his horror. 2001: A Space Odyssey will probably always be what he is remembered for, outside his work on horror. The film’s popularity has not wavered in critical reception, and it is still widely known and referenced more than 60 years after its release.

Kubrick no doubt inspired many in their own quests to make it as directors. His arty shots, zest for new ideas, commitment to his work, and passion to show humans as they really are stands out to many in the industry.He will always be remembered for the fame brought to him by his work. But for some, myself included, this is tainted by his misogyny and the la ck of depth to many of his characters and narratives.