Remember the old days of NES cartridge collecting? That golden age of gaming when the entire concept, hobby, and industry of video games was commonly just referred to as “Nintendo,” when games being cheaper to produce meant the burgeoning home console market was still fresh enough that mechanics and genres were still experimental. Fantasy and adventure games had not yet discovered the perfect formula; even though Square’s flagship series was already underway, the Final Fantasy series was years from taking off in the west. The Legend of Zelda is the major exception, maintaining a firm grip on both nostalgia and endurance thanks to its imagination and accessibility. There is another game that occupies a significant space for me from that era, a fantasy game that did not exactly set any precedents but nonetheless left a profound impact on my neural pathways. That game is Legacy of the Wizard.

Legacy of the Wizard, or Dragon Slayer IV: The Drasle Family in Japan, made its way to North America in 1989, and one copy in particular made its way to the black case full of grey plastic NES cartridges that my cousins owned. It would usually work right away, too, without too much blowing into the cartridge or the system. After a character selection screen, the game dumps you into an apparently bottomless dungeon, where I could wander around for hours without getting bored, something that I never managed to do with The Legend of Zelda.

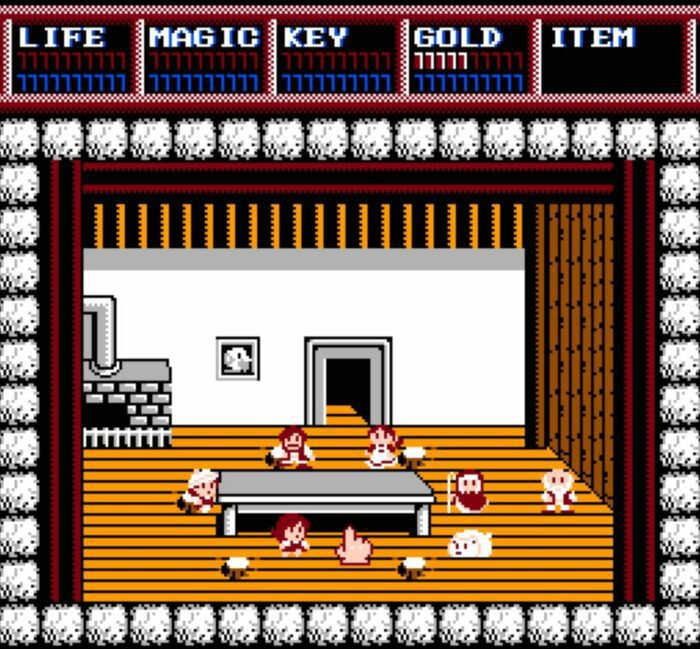

8-bit games often embody a naturally enigmatic quality. Perhaps it is the graphic reliance on solid black backgrounds that allows the player’s imagination to fill the infinite void of the television screen reflection. The sprites and their vague, squarish features resemble hieroglyphs, giving the impression that the game is retelling a story rather than immersing the player completely in the world and experience. Legacy of the Wizard is beautiful at this, opening on a sort of tableau of the family in their humble home, while the use of solid black in the dungeon emphasizes the darkness of the underground dungeon in contrast to the vivid blue sky.

This comfortable representation of home to begin the journey grounds the adventure in a way that Zelda does not; who is Link, and why is he beginning his adventure in the middle of nowhere? With the Drasle family, even the rudimentary structure of the nuclear family gives each character a role in the quest, and the knowledge that the rest of the family is waiting back home relieves some of the stress, but also incentivizes retrying new passages with a different character and thus replaying over and over. Sometimes, you’ll pass through a screen full of enemies, treasure, and blocks only briefly on your way to another, wondering what twisted passage will lead you to the other side of a wall.

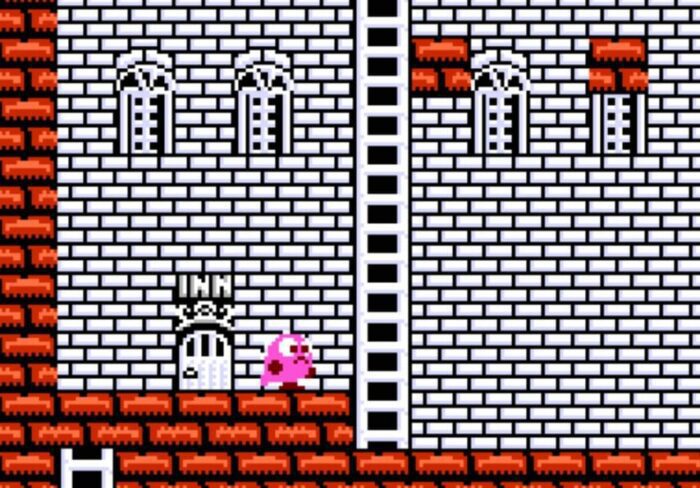

Which brings me to another piece of this game that just drove my curious mind insane. Just after leaving home (interestingly, headed west instead of the traditional left-to-right), the player encounters a gorgeous castle off in the distance. In most games this is the destination, but there is no way of reaching the castle. Instead, we need to backtrack a bit to a ladder descending underground. Legacy of the Wizard offers no clear objective at first, and the castle ultimately serves no purpose other than offering a reference to compare the scale of the dungeon below.

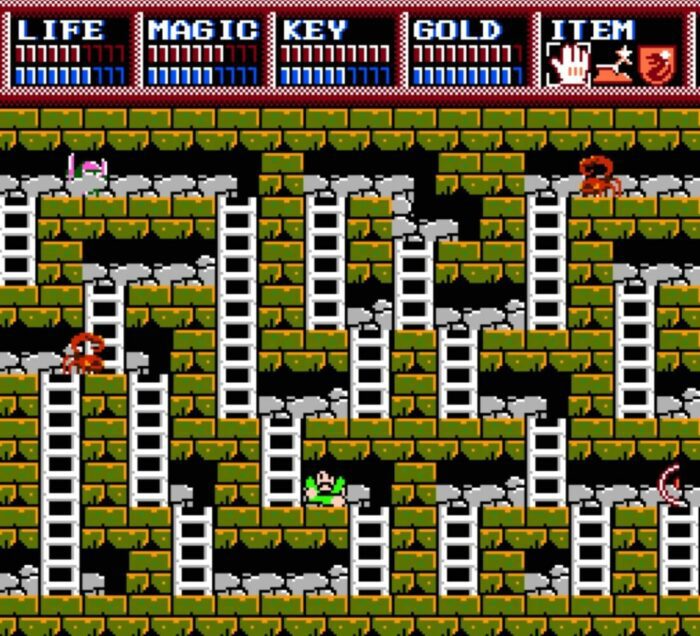

Here’s how I used to play Legacy of the Wizard: most of the time I chose to play as the daughter, Lyll, because she can jump higher than anyone else, and since the only other game mechanic reference I had was Super Mario Bros., but even though I knew that jumping on bad guys was going to kill me, there were places I could only reach through jumping. The bad guys would also respawn, though for a few seconds before springing to life a blinking orb would appear in its place, and you could use this to get a higher platform. Granted, this often required some strategic aiming with your magic, which runs out fast.

If I wanted to last longer, I’d choose the pet, Pochi, because I was under the impression he was invincible, though that’s not exactly true; he’s just ignored by monsters because he is also a monster, which I should have realized since once you’ve chosen him, he transforms from a shaggy dog into a little pink dinosaur. I remember playing as the dad more than once, but I knew you were supposed to save the son for the end, and though I have no memory of playing as the mom, I know I must have at some point.

As a kid, I’d usually just spend about forty-five minutes making my way into the dungeon, finding deeper pits to explore, becoming dumbfounded by the variety in color and layout, and how the changes in sound and images created unique atmospheres, variations on several recurring themes. Mindless wandering is rewarded with bright colors and elaborate mazes that are both claustrophobic and eternal, often spiraling inward toward an apparent dead end for a treasure, only for your character to bump up against a fake wall and descend several screens, landing with a glitchy squeak. The enemies are easily dispatched, but using up all your magic to deal with them leaves you vulnerable. Deadly spikes or the regularly dropped poison are as deadly as the monsters themselves, emphasizing that it is the dungeon itself that is the danger.

It was charmingly addictive in this sense, and looking back, it must have been therapeutic for me, a child with ADHD. Unlike Super Mario Bros., which more or less relied on getting from one side of the screen to the other as fast as possible, or Zelda, which placed too much open space and obstacles between dungeons, and all of them were more or less monotonous in their scenery, sound, and color palette. The key difference is that while those games are objectively better designed, Legacy of the Wizard makes the best use of limited graphics to create a worldspace that is both psychologically distressing and awe-inspiring, even decades later.

After a few screens, you just stumble upon a giant image of a dragon. You can’t approach it; it’s behind an impenetrable frame of dungeon blocks. At one point my cousin blew my mind and told me, “That’s the final boss.” It was legitimately the most epic dragon in video games up until that point. Also it was just right there, the whole time. Imagine if Bowser was just hanging out, silently at the end of World 1-1, frozen, just staring you down. How was I supposed to fight it? Would it just come out and grab me when I wasn’t expecting it? What is happening in this video game? The game never tells. It will just let you wander around for days, lost, completely, passing through screen after screen of humiliating defeat, unable to turn away from the cosmic horror that someone, some endless horde of unfortunate souls, had to build this elaborate prison brick by brick, in order to make the task of slaying this dragon as difficult as possible.

If the dungeons of Zelda were built by competent stone masons, the massive labyrinth of Legacy of the Wizard was designed and completely constructed by coked-up sadists with an endless supply of Lego bricks. Who built this place, and why? Is it the foundation of the castle we see in the distance, or is the family here protecting the inhabitants of that gleaming white palace? Was it the dragon, or an ancient cult dedicated to his worship and resurrection? Was this some Faustian bargain made by the ancestor of the Drasle family, as a misguided attempt at protecting future generations from unleashing this evil? Is this why the family built their modest cabin right above what is ostensibly a bottomless den of monsters? Is the dungeon like the Winchester Mystery House? Are the monsters actually the ghosts of the soldiers the old wizard led into battle against the dragon? Are they the vengeful spirits of the peasants sent to work to their deaths on the construction of this massive tomb?

For a period of time there was a longing for games that maintained the kind of difficulty of the “Metroidvania” type, not just dark and gritty and groundbreaking, but difficult in ways that the hand-holding methods of locating a blinking objective on a map could not satisfy. Dark Souls scratched this itch for a lot of gamers, but Legacy of the Wizard remains an unused template for action RPGs with vast, ever-changing levels in an otherwise open dungeon, with little to go on but just pushing through and figuring it out. It’s not just exploration, but the complexity of the networks and the impossibility of the structure itself, something only 8-bit graphics can render with any coherency.

Of course, Legacy of the Wizard did come with a manual, and there is a proper way to play it if you want to, you know, actually finish the quest. It wasn’t difficult to track down a PDF of the original game manual, which does explain the Drasle family a little further. First, it clarifies why, for all these years, I was referring to the characters as “the son,” “the daughter,” “the mom,” etc., instead of their real names. It is canonical, as they are referred to as both in the manual. I don’t know, this just feels like it codifies something I thought was otherwise very quaint and 80s.

According to the manual, the family’s call to adventure occurs when Pochi brings a dragon scale back to the family home, and Xemn, the father, announces he will slay the dragon locked away deep underground by their wizard ancestor. At first the family protests, until Xemn proposes that instead of fighting the dragon himself, his wife Meyna, and children will aid in recovering the four crowns necessary to unlocking the “Dragonslayer,” the only weapon capable of, well, doing exactly what it says. Once the sword is recovered, the son, Raos, will go take care of the dragon. He is otherwise pretty useless.

There are four bosses defending each crown. With the aid of an online guide, I was able to defeat one of them. There is also a puzzling inventory; it is a little unclear what each of the items are and how to use them within the game, and each character can only have certain items available to them. Xemn and Meyna, both have access to items that move dungeon blocks, opening up new corridors and leading into deeper levels than I ever imagined reaching in all the years I played this growing up.

The dungeon takes on a whole new meaning when the logic behind it starts to reveal itself. No longer meandering without direction, the winding brick mazes turn meditative, and the mystery of the nightmare abyss starts to unravel. As the layers of pixelated basements begin to succumb to their intended design, the repetitive musical loops grow more deliberate in driving the motion across the screen. A sense of complacency replaces wonder. Does Legacy of the Wizard lose some of its magic if you know exactly where to go? Not necessarily. There is a certain rhythm to the exploration once things get going, the format remains unique, and the game is still fun even when you are actually making progress.

Did I, though? No. I’ve never finished Legacy of the Wizard, and truth be told, I don’t think I ever will. It’s actually been quite a while since I even played with a guide, and though I still go back now and then, the ultimate reward for descending into Keela’s dungeon is forgetting exactly why it’s there at all and losing yourself in its strange, forgotten labyrinth. If you want, you can look up maps of the entire thing. I’ve seen them, but I don’t know if they even make it any easier to navigate. I much prefer the manual’s suggestion for a map: make your own.

Excellent article. Personally, I am surprised I have never even played this game. It seems here that it is a very interesting game, and I wonder why more people do not discuss it when talking about games from this era. Makes me want to check it out

I agree. Excellent article. My mum bought this for me instead of Wizards & Warriors. I used to spend hours playing this. It’s so charming and you have articulated it perfectly.

Here’s a Nintendo Power style guide to the game https://bit.ly/legacyofthewizard