Folks, I’ve been publishing movie reviews under primarily journalistic rules for over a decade. I’m a Rotten Tomatoes-approved critic, proud to represent 25YL, but I have to take the wool newsboy hat off for this one. I’ll warn you right now. This review is going to be a first-person point-of-view rather than a journalist’s third person point-of-view, and it’s going to get ugly. The Tree of Life can’t be reviewed by me without it.

According to Wikipedia, conceptually, the idea of a “tree of life” symbolizes the religious, scientific, and philosophical notion that all life on Earth is invariably connected. The term could be interpreted as a metaphor for the common origins of evolution, the planet’s interconnection of all things, or the livelihood of an ethereal spirit. It appears in Chinese, Indian, Norse, Egyptian, Jewish, and Mesoamerican mythologies. J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis have put their own versions of the “tree of life” in their literature. You can even say movies like Darren Aronosky’s The Fountain and even Avatar‘s “Home Tree” borrow from the ideology.

On paper and as a visual, I dig it and accept it. That’s an ambitiously universal and fascinating thing to study cinematically. Such imagery could can hook an audience of all different dispositions and beliefs, from the Lost-like “man of faith” John Locke to the opposing “man of science” Jack Shepherd. I get that.

If there’s a filmmaker existential enough and visually surrealistic enough to wrap that idea around a head with celluloid film, it would be the reclusive Terrence Malick. From his resume of Badlands, Days of Heaven, The Thin Red Line, and The New World, he carries the industry-anointed “misunderstood genius” tag, like Stanley Kubrick before him. Well, he’s earned it. His work is, to his credit, different and more visually rich than anything his contemporaries and peers are doing in Hollywood. As a cinephile, I get that. Bravo.

However, he earns the “misunderstood” part to the label because of a baffling method of storytelling in his films. Anyone who’s seen his last previous films (The Thin Red Line and The New World) will know what I’m talking about. Even if you know the WWII Battle of Guadalcanal or the story of Pocahontas, you’ll still need a road map, a 5-Hour Energy, headphones to hear the whispers, and tape to hold open your eyes.

His The Tree of Life is another film of that challenging and incoherent mold. It was the winner of the prestigious Palme d’Or, the highest prize of the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, where it received an odd mix applause and boos. Selection jury chair Robert DeNiro offered “It had the size, the importance, the intention, whatever you want to call it, that seemed to fit the prize.” The film earned a perfect 4-star review from Roger Ebert, topped over a dozen year-end best lists, led Variety‘s “best of the decade” list, was ranked 7th for the new century by the BBC, was gilded a Criterion inclusion, and carries an 85% rating on Rotten Tomatoes to this day. It’s supposed to be a pillar among pillars. We’re all supposed to genuflect.

I’m not an experienced renaissance man of film like DeNiro or anywhere near the critic Ebert is, but, forgive me, I didn’t see a single shred of a point behind The Tree of Life. Don’t get me wrong, I’m an open-minded guy and savvy enough to see the artistic point of cinema. Knowing the metaphor the title alludes to, I can tip my hat (yeah, that snobby wool one again) to a creative filmmaker tackling something that deep and ambitious, but that’s it. I can pay attention to just about any tedious or extreme movie you put in front of me, but I couldn’t stop looking at my watch to wonder when the brain-draining torture was going to end.

From what I can muster, the winding plot follows a 1950s Waco, Texas family that, on the surface, fits the bill of its typical period stereotypes. Academy Award nominee Brad Pitt plays Mr. O’Brien, a strict father who runs a tight ship of expectations towards his wife and three sons, particularly his oldest son, Jack. He’s a man with an artistic and soulful side deep in there somewhere, but can’t seem to connect with his sons without forced affection. Up-and-coming actress Jessica Chastain plays Mrs. O’Brien, the angelically gentle and beautiful mother who the children favor during their long days while their father works.

As soon as we are introduced to them in the 1950s, we are taken to the present where we meet Jack as an adult, played by two-time Oscar winner Sean Penn. He’s a successful, suit-clad architect now, but seems to wander through life as lost as he did in his youth. We learn, as we briefly do in the ’50s introduction, that he and his family continue to mourn the off-screen loss of one of his younger brothers. The story we are seeing of his youth is his troubled reminiscence to years before that untimely death.

All of a sudden, POOF! and WTF! Malick cuts to a lengthy (30 minute-plus) dramatization of the Big Bang, formation of the universe and solar system, and the beginnings of life on Earth. It’s an impressive display (no doubt about that) of digital effects (courtesy of 2001: A Space Odyssey‘s legendary effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull) for an old-timer filmmaker who doesn’t embrace them. On the other hand, watching lava, bacteria, single-celled amoebas, and, later, meandering dinosaurs grinds the movie to an absolute crawl of sleep-inducing imagery. It’s supposed to resonate as a deep connection to life on Earth, but ends up feeling like a fancy Discovery Channel/BBC evolution documentary with a bigger budget, no obligatory Sir Richard Attenborough narration, prettier music (from since Oscar-winning composer Alexandre Desplat), and all of the boredom possible.

Exiting that sequence, the Desplat score continues and Malick tries to extend and connect that sequence into an edited montage of the beginning of the O’Brien family, showing the birth and growth of each of the three sons, but it just doesn’t fit together, even with the idea of the “tree of life” in mind. Once you’re brought back to the 1950s we were introduced to, with an adolescent Jack (first time actor Hunter McCracken), the story begins and Sean Penn disappears for an hour-and-a-half.

I guess we were going to learn how his upbringing made him into the lost adult. OK. I lean forward in my seat, ready to see the Brad Pitt from ten years ago continue to emerge as a true mature actor. Does that happen? Nope.

For those of you who are in your 40s (like me), with parents who likely grew up in the 1950s, you have heard stories about the absolutely dull and stupid things they did as kids to occupy their time in a pre-television age. You know: throwing rocks, kick-the-can, abusing animals, going to church, endless chores, and wannabe Stand By Me moments of friendship and discovery. Well, imagine that ridiculous boredom filmed for nearly two hours, with tiny moments of Pitt parenting and Chastain looking like the Virgin Mary. That’s it. That’s the storytelling scope of The Tree of Life.

It’s all made worse by a nearly absolute lack of dialogue and conversation, replaced by eerie whispered and versed poetic voiceover fragments of sentences from all the characters…FOR TWO HOURS. As a film guy, I get it. Like I said, after seeing his last two films, that deep poetry and use of voiceovers gazing into his characters’ inner thoughts and emotions is his artistic style. For some people, I’m sure it’s fascinating, different, and richly artistic, but not here. To think there was a possible six-hour cut of The Tree of Life, oye!

If that’s not enough, the movie randomly peppers shots of unrelated natural imagery (from daring cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki) of all kinds. Intermittently, every three to fives minutes or so, there’s a shot of a tree, the caves from 127 Hours, blades of grass, random skyscrapers, another tree, stained glass church windows, regular windows, candle glow, another tree, clouds, an empty house, another tree, window drapes, waterfalls, another tree, etc. Again, I get it. Malick has had that very nature-connecting visual style. I’m sure some people find it gorgeous, but DAMN.

What’s worse is that all of these shots of rapturous beauty slices the movie to ribbons. A team of five (yes, five) editors—including previous Oscar nominee Daniel Rezende (City of God), future Oscar nominee Hank Corwin (The Big Short), Malick’s confidante Billy Weber, and Jim Jarmusch’s go-to Jay Rabinowicz—slaughters any momentum with the constant inserts. The average shot length of this movie is a shade over six seconds, a number a shade quicker than the usual from Wes Anderson. Sure, that’s double a Michael Bay Transformers film’s number in the 3s, but that’s less than half of Kelly Reichardt’s new First Cow and its 15.1 ASL. The Tree of Life feels like a precursor to the currently en vogue medium of “slow cinema” while qualifying as a hot rod for that descriptor’s pacing.

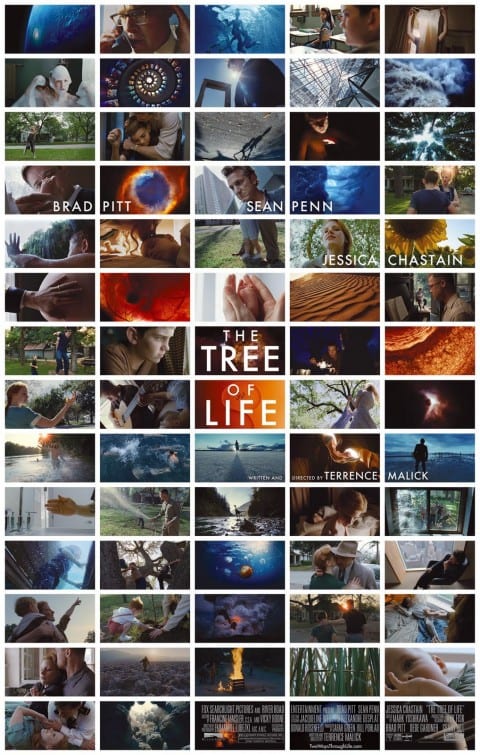

If you want a shorter explanation and visualization of how it feels to sit through The Tree of Life, take its lobby poster, a collection of the film’s images. Display each one of the pictures, slowly with subtle PhotoStory/PowerPoint animated movement, put some classical music on, and then read the Book of Job for nearly three hours. Even shorter, if you want the movie in 15 seconds, stack those images and flick them like an old-school flip book. That’s it. That’s also as much you learn.

By the time we see Sean Penn again (90 minutes later), aimlessly wandering through a weird coastal rocky plain after aimlessly wandering through a skyscrapered city, we’ve been worn out from all the imagery and camera work. If you haven’t been lost or disinterested by then, you soon will be when Penn clears the rocks and meets, with stares and embraces, all of our movie’s characters, even those from his youth, including his younger self, on a sandbar beach with the ocean lapping by everyone’s feet. Is he dead? Is he in heaven? Is he hallucinating at the end of the world? Who the f*ck knows. You’ll exit wanting three hours of your life back, a long hug, some ice cream, and your brain reprogrammed.

One thing the film does sketch out and say out loud early is that there are two ways through life. One way is the “way of nature.” This signifies the evolutionary process of living, growing, dying, and the world moving along after you. Supposedly, some of our characters are living embodiments of this path. Jack, both as a adolescent and as an adult, wrestles with this way and the second way. Remember, I didn’t see a shred of a point to The Tree of Life. I’m just repeating what I was told. Brad Pitt will hit me if I don’t.

The second defined way through life spun by the film is the “way of grace.” This way is shown through the family’s devout religious faith and the commonly-held beliefs in the human soul, spirit, and an afterlife that follows our Earthly time. This is also symbolically shown through various characters (though not as clearly as in, say, Charles Dickens’s The Christmas Carol) and wrestled upon by Jack. In both ways, the characters’ voiceovers will illustrate shades to one or the other.

After that, the best I can muster is to attest that the 1950s sucked. Wow, no wonder why everyone went off the chain with drugs, free love, and the music of the late 1960s. After growing up in that kind of rigid strictness, unending boredom, and oppressive parenting, you would lash out and be a burned out soul later in life too. Sheez. I feel like the 1950s should be described the way Austin Powers described the 1970 and 1980s to Felicity Shagwell in Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me: “You’re not missing anything, believe me. I’ve looked into it. There’s a gas shortage and A Flock of Seagulls. That’s about it.”

I watched it. It is about God, suffering, love, loss, and redemption. Big questions.

I am not a film critic. But this was pretty obvious, I thought.

This is probably the most enjoyable scathing review of something I love this much. I give Mr. Shanahan full marks. For people who hate this film for these reasons, I don’t think there is anything you could say to get them to like it. They just move through the world differently.

“f that’s not enough, the movie randomly peppers shots of unrelated natural imagery (from daring cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki) of all kinds. Intermittently, every three to fives minutes or so, there’s a shot of a tree, the caves from 127 Hours, blades of grass, random skyscrapers, another tree, stained glass church windows, regular windows, candle glow, another tree, clouds, an empty house, another tree, window drapes, waterfalls, another tree, etc. Again, I get it. Malick has had that very nature-connecting visual style. I’m sure some people find it gorgeous, but DAMN.” – if this is your experience of the world already, that imagery just makes intuitive sense. If it is not, how can you explain it?

Or this: “If you want a shorter explanation and visualization of how it feels to sit through The Tree of Life, take its lobby poster, a collection of the film’s images. Display each one of the pictures, slowly with subtle PhotoStory/PowerPoint animated movement, put some classical music on, and then read the Book of Job for nearly three hours. Even shorter, if you want the movie in 15 seconds, stack those images and flick them like an old-school flip book. That’s it. That’s also as much you learn.”

What a perfectly accurate description! The only thing I would add is that its a carefully curated list of images and music that innovatively relates to the text of the book of Job. If that experience would be horrible rather than great to you, then you will not like this film. That’s fair!

I know this response is way late (but frankly so was the review) but thank you. It was funny, enjoyable, and very very accurate.

I gotta say I came looking for this review. The movie was absolutely terrible, top 5 worst movies I have ever seen. Anyone trying to give this garbage meaning must have one hell of an imagination.

I’ll add that any movie that requires this much imagination to find meaning in is totally missing the mark. I can appreciate ambiguity, this film isn’t ambiguous, just a vacuum of any meaning at all.

You have written long and succinctly from your current point of view.

But you watched a screen play that unfortunately does not fit your current state of mind.

Watch it again in 25 years and you may make sense to what what lies behind the images.

For describing a movie you claim not to have a shred of a point you certainly wrote much. I would encourage you to watch it again with a growth mindset. Malick is a reader, a thinker, a teller of tale through images of beauty and philosophical musings. He expects much of his audience. That they will be readers of the Bible, of Plato’s dialogues and Saint Augustine, and Marilynne Robinson’s essays and probably much I’ve left out. For those willing to work and think, some of the finer points of the complexity and depth of being human that Malick is trying to make may begin to show forth. That said, it is also true that one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. You write rather well despite my disagreeing wholeheartedly with your opinions.