There is a surplus of fan-favorite quotable lines in Twin Peaks Episode 4, and I think the chewiest is when Audrey Horne tells Donna Hayward, “In real life, there is no algebra.”

There is a telling irony in this quip. On the surface, Audrey’s articulating with all the confidence of a high school teenager how useless she feels her math education is to what matters in life. And yet, Audrey pivots right into asking Donna questions that will help her figure out who killed Laura Palmer. Audrey desperately wants to solve for X so she can secure the attention and love of Agent Cooper. Algebra is a system of substituting signs and symbols for missing information in order to facilitate a process of putting pieces together. Simply put, Audrey is actively doing algebra, and so is nearly everyone else in this episode, as scene after scene features investigations, new clues, and epiphanies.

What follows is a map of the episode’s algebra, with close attention to the more intense equations.

Opening the episode is an eerie, floating shot of the Palmer house. It’s better to say “a” Palmer house, though, since this is not the iconic house that features more prominently throughout the series. While this alternative house may be of use in building theories of multiple timelines in the wake of Season 3, what I find more intriguing is the unsettlingly unidentified point of view conjured through the camera movement. The motion implies a force, an agency, or the sense of a dream without a dreamer. It’s eerie because we get the feeling there’s an agent focalizing what would typically be an objective establishing shot. As an algebra equation, this beginning prompts us to wonder if there’s an X to solve for that’s deeper into the grain of the place and plot than the previous episodes have suggested.

Inside the Palmer house, the transfer of an image from Sarah Palmer’s internal vision to an investigation-ready sketch is underway. As the camera movement and cutting circulate around the living room, there’s an emphasis on faces: Sarah Palmer’s as she re-experiences the trauma of her vision, and that vision as a metonymy of the trauma of losing Laura; Deputy Andy Brennan’s face of concentration as he combines active listening with artistic acumen, bolstering the alternative masculinity he’s brought to the series from his first appearance in the Pilot; and the face of the man in Sarah’s vision. She describes his hair as “grey-on-grey.” That line is a tautology, but just like Audrey on algebra, Sarah’s impression also contains the multiplicity of something that is more than one but not quite two.

Leland Palmer emerges from behind a screen in the living room. He has been in the scene the whole time, yet we didn’t see him. Leland is a person who is there and not there, observing while not being observed. He draws everyone’s attention when he shares that Sarah has, in fact, had two visions. He delivers this news with a vocal tone and body language that make it a barb aimed at Sarah, and her facial reaction and vocal tone reply to Leland in kind. There’s a domestic code at work here, an algebra of aggression and something else that only these two know.

As he speaks, Leland is framed by the camera with a painting in the background of a person that makes a visual near-rhyme with his posture and the color of his robe. That an artistic rendering in the room rhymes with him operates like an unconscious clue that there might be another artistic rendering in the room that connects with Leland. So, if we retrace the signals in the show that point at Leland, this scene is one, whether intentionally made that way or not.

The scene ends with a close-up of Donna’s face as she reacts to Sarah recounting how her second vision included the excavation of the necklace that Donna and James buried together. Donna manages to hold her face steady so that no one in the room will observe her inner turmoil and desire to find out if there is an X regarding that necklace that she and James would then have to solve for. Underscoring her duality in the moment is an audio bleed of the opening from the soap opera within Twin Peaks, Invitation to Love, then a cut to Lucy Moran as she summarizes the current episode to Sheriff Truman and Deputy Andy.

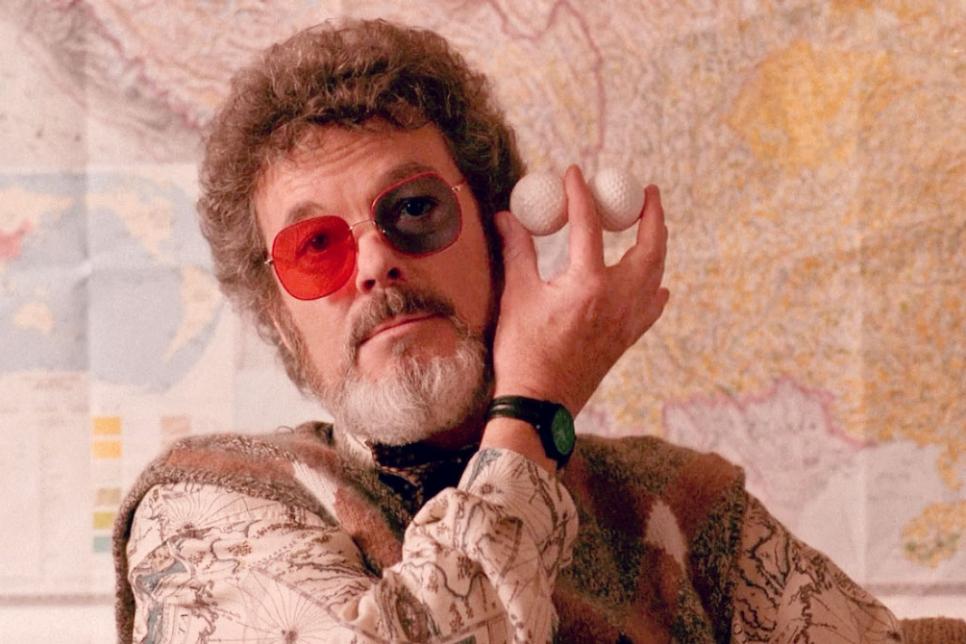

Now the episode shifts into another scene of investigation and interrogation. Visually, the scene opens on Dr. Jacoby, a local psychiatrist, who is holding two golf balls between three fingers. The golf balls held at the same level as his eyes, which are already a focal point due to his red-blue 3D glasses, make another visual rhyme in the episode. They look like a second set of eyeballs, but one that does not see.

Jacoby then creates the illusion of magic as he seems to pop one of the golf balls into his own ear and then produces a golf ball from his mouth. Cooper observes the performance without comment and with a facial expression of what seems like exasperation barely contained by the need to ensure the doctor will be a cooperative witness.

As a viewer, it’s easy to be pulled into Cooper’s dismissive reaction to Jacoby’s show, for, as many critics point out, Cooper is the avatar and point of identification for viewers who are also outsiders entering the town of Twin Peaks and trying to uncover its secrets and solve its mysteries. But disentangle yourself from Cooper, and Jacoby’s sleight of hand tells a truth in the form of a lie. Those things that enter the ear and come out of the mouth are illusions. They are real, just as the golf balls are real, but they’re deployed with misdirection to lead to false conclusions.

This is one of the early scenes that fit into the grand unifying theory, half-baked by a good friend and me, that Twin Peaks is actually Dr. Jacoby’s hypnotism stage show in Vegas.

Costuming is key, too. Jacoby’s shirt is a map, so it reinforces the visual signal of the map behind him in the scene. In the course of the scene, Jacoby stands at the map and delivers a pseudo-Freudian lecture to Cooper that asserts all of our society’s problems are of a sexual nature. By a map of Tibet, Jacoby says the solution is that X is sex. Just two episodes earlier, Cooper stood at the map of Tibet and says that to solve for X he will throw stones at a glass bottle. Both investigators synchronize the logic of ratiocination with realms of symbolic algebra that exist beyond the conscious human mind.

Is it their similarity, rather than their difference, that might be behind Cooper’s nearly hostile dismissal of Jacoby?

It’s worth a calm consideration, and as you ponder their connection, note how this scene ends with a shot of Cooper seated while Jacoby leans close to his left ear and semi-whispers, “Laura had secrets.” The two-person tableau resembles Laura leaning close to Cooper’s left ear in the Red Room to whisper some of those secrets. How can Jacoby replicate Cooper and Laura? Unless this is his hypnosis show in Vegas.

Gordon Cole’s first “appearance” follows next. In a shot from the far end of the conference table, Cooper is shown putting Cole’s call to the DUOFONE speaker and informing Sheriff Truman, “This is my supervisor.” If MST3K were riffing the episode, they’d do the old, “No it isn’t, that’s a speakerphone” gag here. What I find striking in the scene is Cooper’s approach to Cole, rather than what Cole says. The special agent embodies his impatience and frustration with Albert’s request to remove Truman from the office due to their physical altercation by leaning into the conference table in a gesture that looks a lot like the desk pushups “Battling Bud” Mullins does in Season 3. What’s more, Cooper cuts off Cole midsentence when he hangs up. He’s really rattled, but is it more by the algebra of solving who murdered Laura or by disturbances to the ideal image of himself he holds and tries to project?

Next stop: Timber Falls Motel. After Cooper’s abruptly curtailed call with Cole, Hawk rings to say he’s found the One-Armed Man at the aforementioned motel. Three storylines connect, and they each contain multiple algebra problems. Bookending the scene is Josie Packard. First, she conducts a private investigator-style stakeout of Ben Horne and Catherine Martell, who are mixing pleasure and business in a motel room. By the end, Josie has already driven away, likely in response to the arrival of the Sheriff’s Department.

Deputy Hawk alerts Sheriff Truman to the remainder of her stakeout, a round pool of engine oil surrounded by dry pine needles. The first bookend follows through on Josie’s discovery that Catherine and Ben have been keeping two ledgers for the Packard Sawmill; the flavor is classic noir. The second bookend, though, gestures at the pool of scorched engine oil that marks the portal between dimensions; the flavor is a weird blend of petroculture and the supernatural. Even though this episode aired well before the concept of the Anthropocene was emerging into the social imaginary, the combination of petroleum, timber extractivism, and another world making itself felt appear in retrospect to be clairvoyant.

The Ben-Catherine segment of the scene contains what I consider an inconsistency in character. Catherine unhesitatingly reveals her second secret hiding place to Ben, one so secret not even Pete the Poodle, as she refers to her husband here, knows about it. Was Ben such a sex magician that Catherine’s experiencing an extreme form of pillow talk? The oddball “give Little Elvis a bath” joke makes it clear Ben believes he’s a hunka-hunk of burning love. But Catherine doesn’t appear similarly vulnerable before or after this info slip. Up to now, I’ve found this an inconsistency in her characterization, but if you have ideas about its possible meaning.

The third storyline is that of Phillip Gerard, the One-Armed Man. When the officers break into Gerard’s motel room and Truman orders, “Get your hands where I can see them,” there’s a palpable beat before the scene continues. The pause isn’t for a laugh. Instead, the subtle facial performance by Michael Ontkean as Truman expresses the uncomfortable dissonance between his automatic script for confrontation and Gerard’s visible disability. In fact, Truman’s discomfort is amplified by Gerard’s vulnerability, as he’s freshly out of the shower and donning only a towel wrapped about his waist.

My friend Emma Busch has written about disability in David Lynch’s work for 25YL, and this scene fits into that area of critical analysis. Of special note is Gerard’s vulnerability here: not only is he practically nude and therefore exposed in terms of his disability and his general body, but his distraught tears when coerced to tell Cooper what was tattooed on his arm shade Gerard as an empathetic figure. Is that vulnerability a judo move that’s later leveraged to throw the viewers into seeing Gerard as a holder of power? Or is his vulnerability the cornerstone of his capacity to hold power later in the narrative arc?

Whichever answer you choose, you’ll have to account for the fact that he once was but has walked away from selling pharmaceuticals. He was part of the legal recto of for-profit drug dealing that’s shadowed by the many illegal verso side-dealers in the series. And the two sides are different yet mutually imbricated, just as I would say that the towns of Twin Peaks and Deer Meadow are dichotomous but bound to each other as if they mutually constitute each other’s existence.

As a last thought on the Timber Falls Motel, on this rewatch I noticed the audio presence of one or more woodpeckers in the outdoor shots. Nonhuman beings, specifically birds, are looking for what is hidden in the woods. Woodpecker algebra, and in this episode the woodpecker itself, opens a bird-mystery X that gets collaboratively solved: the answer is a Mynah bird named Waldo, owned by Jacques Renault.

Now, there are a lot of strange things in this episode, but what I find far and away the strangest is the parole board that hears Hank Jennings make his case and decides to grant him parole. As other critics and scholars have noted, Twin Peaks features an extremely white cast, and the few people of color in the series present deeply problematic representations. With the parole board, suddenly there are two people of color, not just in the same scene, but in the same position. To see an African American man and woman holding legal power over an incarcerated white man is an inversion of the predominant conditions of incarceration in the U.S. What ideological buttons does their presence push in which audience demographics? And how does Hank’s whitemansplaining to them his abstract conception of how fate and his crime and punishment are bound together enhance the ideological button-pushing?

These questions and the identity politics embodied in the parole board that sparks them are, I would argue, much more significant surreal touches than that llama in Dr. Lydecker’s vet clinic.

While on the topic of the political unconscious in Twin Peaks, there’s a scene not long after the parole board hearing where Cooper, Truman, Hawk, and Andy head to the Sheriff’s Department basement gun range in response to Andy’s firearm mishap at the Timber Falls Motel. Agent Cooper reveals a strain of sexism in his worldview when he instructs Andy to stop trying to understand Lucy’s recent hostility towards him: “No logic at work there, Andy. Best to let that one go. In the grand design, women were drawn from a different set of blueprints.” The other three men reply with “Amen,” and they take their guns in their own hands and shoot some bullets.

In the same scene, Cooper tells Truman he’s never been married but that he’s been with someone who taught him about commitment, responsibility, and so on. Tellingly, what that relationship meant to Cooper is articulated entirely in response to himself and where he feels he failed. The agency of love remains comfortably in the man’s possession. This is a piece in the puzzle of how misogyny manifests in Agent Cooper.

One of the most emotionally sincere and challenging scenes in this episode, perhaps in the series as a whole, unfolds between Ben and Audrey Horne. At first, the camera approaches Ben from above and behind him. The business mogul is riding a stationary bike while moving negotiations along with Icelandic investors who are interested in the Ghostwood Development. The whir of the bike that is spinning yet going nowhere combines the needle-on-vinyl-groove sonic image that David Lynch returns to time and again, and in this case, it also mimics the ringing sound that haunts Ben in his office during Season 3 and connects to his reminiscence of the Schwinn bike his father gave him when he was a child (“I loved that bike”). This later moment comes as he contemplates his grandson’s hit-and-run manslaughter of a child, and Ben internalizes this as a paternal crisis, the lack of a father. That’s a powerful scene that loops back to the moment in this Season 1 episode where Audrey says, “Please let me be your daughter again.”

Sherilyn Fenn and Richard Beymer deliver stellar performances around that line. She is manipulating him but is sincere, indicated by a catch in her voice during the line. Yet she takes a turn when spotting a photo of her and Laura on her father’s desk. Ben, for his part, appears genuinely to shift out of his real estate scheming mode in response to her plea, but he also turns immediately back that way when a call comes through. This is a scene to watch and rewatch. The algebra is crazy-subtle.

Tennis at Jacques’ apartment complex? I love this goofy X dropped into the episode. Is it something to solve for, or is it simply a foil—a reminder that quotidian life outside the realms of drug dealing and murder is also a weird spectacle?

Finally, Josie, fishing, and a domino and its likeness end the episode in a confluence of loops. In the final scene, the fish isn’t in the percolator. Instead, Pete invites Josie to partner up with him for a mixed-doubles tournament where the algebra is the successful baiting and outwitting of nonhuman beings by angling toward X. After Josie agrees to the proposal, there’s a doubling of “Sweet dreams” between them—multiple dreams and dreamers.

But before any sweet dreams, Pete leaves the scene, and Josie is juxtaposed and accentuated through a canted camera angle with the taxidermied bodies of other nonhuman beings who haunt the rooms of Blue Pine Lodge. These beings go on for others, suspended at a moment in time past which they’ll never age, not unlike Laura Palmer in the minds of all who live in Twin Peaks. In the foreground of the shot is a clock, pointing to the weird temporality making itself felt by Josie as she receives a telephone call from Hank Jennings. In Hank’s hand, while he asks her simply if she got his message, is a domino. It’s a little slab of plastic, a piece in a game—not unlike the dice that pop up across Season 3, and it exerts an unexplained power of dread over Josie. Hank’s message was a drawing of this small plastic game piece. As such, the domino is elsewhere, in Hank’s hand, yet also right there in the room with Josie in its mediated form. And this doppelganger domino is a pencil-on-paper likeness that recalls Andy’s sketch of BOB in the opening scene.

It turns out that the algebraic X of Twin Peaks exists as a nexus point where multiple equations meet, even as they extend into diverse dimensions.