While the first major release from future cinematic powerhouse Christopher Nolan technically premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2000, Memento debuted in American cinemas in March of 2001 and works as an example of the growing bridge between 20th and 21st century filmmaking.

Nolan’s first picture, a short, verite noir shot on the streets of London called Following (starring his childhood friend Jeremy Theobald) staked his claim as an innovative new voice in cinema when it was released in 1999, but Nolan—despite being a British national, as well as a dual American citizen thanks to his parentage—struggled to find anyone in the British film industry interested in bankrolling Memento, a picture which took a skewed impression of film noir and projected it through a syuzhet-scrambling prism.

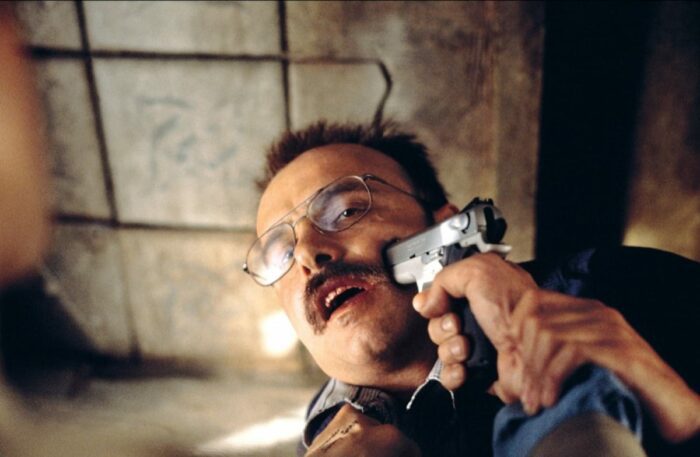

The story, developed in tandem with Nolan’s brother and co-writer Jonathan’s own short story called ‘Memento Mori’, revolves around insurance investigator Leonard (Guy Pearce), who we see at the very beginning execute a man, ‘Teddy’ (played by Joe Napolitano), in cold blood before the narrative unfolds backwards, scene by scene, with the gambit of Leonard having ‘anterograde amnesia’, a rare condition which results in the brain being unable to store recent memories.

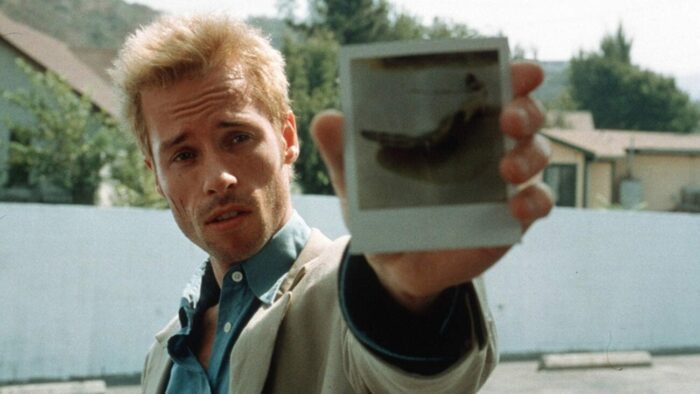

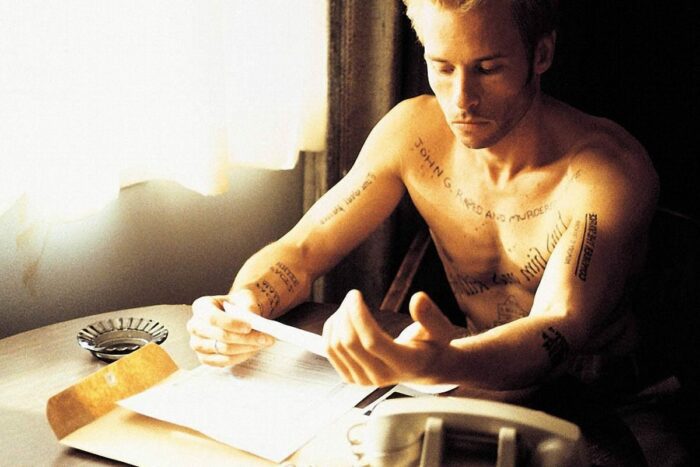

Leonard literally cannot remember what happened in the previous scene we then watch, with the character forced to decode clues tattooed on his body and write himself notes on polaroids with clues that will help him understand the mystery of who murdered his wife—a mysterious figure called John G. Simultaneously, in black and white sequences, we see Leonard at an indeterminate point of time telling a story on the phone of a client, Sammy Jankis (Steven Tobolowsky), suffering from a similar amnesia, which may be the key to decrypting his wife’s murder.

An oft-unrecognised Rosetta Stone to Nolan’s films is that they are deceptively simple at heart, merely wrapped up in his own unique sense of stylistic puzzle box enigma. Nolan himself has claimed as much, as recounted in Creative Screenwriting:

[T]he whole dynamic of the script is aimed at taking a really very simple story and putting the audience through the perpetual distortion that Leonard suffers, thereby making this simple story seem incredibly complex and challenging, the way it would be for someone with this condition. Which isn’t to say that there aren’t all kinds of complexities at the end of the story, but the basic plotting is actually very simple.

Memento, despite the ingenious non-linear structure and inversion of the established tropes of film noir (the corrupt cop, the femme fatale, the careworn and dogged investigator, urban decay), boils down to a psychological trick, as do many of Nolan’s films. Insomnia uses murder in the cold, ceaseless Alaskan daylight to frame the compromised morality of a cop in tandem with a killer. The Prestige presents itself as a gigantic piece of theatre staged against the audience but the biggest trick is that there *is* no trick. Inception dresses up the planting of a simple idea with grand, operatic, action spectacle theatrics. Nolan is as much a showman as The Prestige’s Robert Angier, and some consequently decry his films as pure artifice, lacking any kind of substance beneath the veneer.

Memento rejects that supposition entirely. It might play as a deliberately straightforward story if you reverse the scenes, as the studio enforced on the eventual DVD release against Nolan’s wishes, but there is a much deeper level of psychology underpinning what turns out to be a nihilistic, fruitless search for a truth that will always evade Leonard: that not only does he murder the wrong man at the beginning of the film, but the man he is looking for is long dead, and ultimately he is chiefly responsible for his wife’s tragic fate and has constructed his own puzzle on a subconscious level to cope with this reality.

Darren Mooney in his book Christopher Nolan: A Critical Study of the Films contends that Memento engages with the text in the form of ‘narrative as conspiracy theory’:

Leonard fashions an epic narrative around the death of his wife, positioning himself as a lone crusader hoping to avenge her death. He concocts an elaborate mythology about her murder scrounged together from incomplete information and vague clues that provide him with a sense of purpose ands direction. There are drug dealers and warnings, torn pages and redacted information … Leonard cannot imagine a world without an enemy against which he might define himself, so he cultivates a conspiracy and a mythology to imbue his life with a grander sense of purpose.

The ‘90s were, of course, a cornucopia of resurgent interest in conspiracy theory, with phenomena on television such as The X-Files helping to foster an inherent American cultural distrust of big government, echoing similar sentiments in the post-Nixon, global recession era of the 1970s which saw a raft of popular, successful conspiracy thriller pictures.

Memento utilises the twisted building blocks of film noir to align itself with the idea of internal conspiracy, that we may not be able to trust ourselves, let alone the kind of big government who just months before Memento’s release had seen the two-term Clinton Administration give way to the George. W. Bush. Jr era following a controversial, contested Presidential election at the end of 2000 in which voter fraud in the swing state of Florida was hugely suspected, and remains a topic of uncertainty two decades on. 2001 began with a Republican government who would inherit the mantle of a White House deeply mistrusted by vast swathes of the populous, and would soon become part of a swirl of post-9/11 conspiracy theory not so potently witnessed since the Kennedy assassination’s aftermath.

That’s another key to Nolan’s films. They might appear to involve external reality and broad, grand statements, but they often resolve themselves to an internal, almost mythic journey for the (always) male protagonists. Bruce Wayne might don the costume and become Batman but the entire Dark Knight trilogy concerns his own haunted psychology regarding the indiscriminate murder of his parents, and the lawlessness of modern society that encourages him to become a symbol of justice.

Inception’s Cobb constructs labyrinthian dream realities to accomplish his machiavellian goals as the ultimate grifter, but he is trapped by the spectre of his undead wife. Interstellar‘s Cooper might traverse space and time in order to find a suitable new earth for colonisation, but all he really seeks to do is get back to his daughter. Leonard is Nolan’s first true protagonist on this journey inward, as he seeks to resolve his own loss by constructing a grand narrative beyond himself, but this works as the recurring trope in the lexicon of Nolan’s films beyond Memento.

What Memento demonstrates is a willingness to challenge audience perceptions about narrative in a way that deepens the embrace of non-linear structure Quentin Tarantino favoured in Pulp Fiction during the mid-90’s, but Nolan is one of the few filmmakers who after 2001 manages to transform these smaller, low budget puzzles into broad, sweeping, popular entertainment. Similar emerging filmmakers of the same era such as Darren Aronofsky or even more so, Shane Carruth, who with pictures such as Pi or Primer confounded audiences with a willingness to push at the edges of accepted reality, have struggled to emerge as an industry of their own as Nolan has.

Nolan managed to transpose his stylistic framework onto the popular consciousness by making his films intelligent without being alienating, though he subsequently has been accused of high-mindedness and conservatism as a result. Ultimately, you get the sense Nolan values emotion before construction, even if that isn’t immediately apparent. Michael Caine’s Cutler in The Prestige may assert that “you want to be fooled”, but this too may be a trick. Nolan wants us to understand, on a thematic level.

You do understand Memento on that basis. The intricacies may still baffle, but as an audience we can read what Leonard is seeking to achieve, that catharsis. The chilling warning Nolan provides, however, is that we may not be ready to embrace such a reality. He frames this when discussing the ending:

The most interesting part of that for me is that audiences seem very unwilling to believe the stuff that Teddy [Pantoliano] says at the end and yet why? I think it’s because people have spent the entire film looking at Leonard’s photograph of Teddy, with the caption: “Don’t believe his lies.” That image really stays in people’s heads, and they still prefer to trust that image even after we make it very clear that Leonard’s visual recollection is completely questionable. It was quite surprising, and it wasn’t planned. What was always planned was that we don’t ever step completely outside Leonard’s head, and that we keep the audience in that interpretive mode of trying to analyze what they want to believe or not. For me, the crux of the movie is that the one guy who might actually be the authority on the truth of what happened is played by Joe Pantoliano… who is so untrustworthy, especially given the baggage he carries in from his other movies: he’s already seen by audiences as this character actor who’s always unreliable. I find it very frightening, really, the level of uncertainty and malevolence Joe brings to the film.

Nolan’s assertion is that while Leonard brings his own sense of confirmation bias to proceedings in Memento, so might we as an audience. The world after 2001 will increasingly question the veracity of memory and the power of truth, and as a filmmaker who has often sensed the way the cultural wind is blowing and who very much explores the post-9/11 landscape of reactionary politics and terror in his films, Nolan’s striking first film emerges from the assured calm of the ‘90s headlong into a kaleidoscopic decade of narrative instability.

James Mooney perhaps contextualises this well:

At the end of Memento, Teddy reveals ‘the truth’ about the assault and the death of Leonard’s wife. This perhaps throws some light on Teddy’s particular use of the term ‘incident’ in the conversation referenced above. Many critics have debated whether Teddy’s testimony is to be trusted, however, there is a reveal earlier in the film which may establish this (Nolan himself has stated that the answer is in the film). What this twist shows, is that sometimes our memories deceive us, or rather, sometimes we deceive ourselves by ‘choosing’ to forget or by manipulating our memories of past events.

Whose lies do we believe, in the end? The world’s or our own?

Haha! Excellent idea, you’re welcome. Thanks for reading, Michael & hope you enjoy your eventual rewatch!

Fabulous piece, A. J. Makes me want to re-watch MEMENTO again, something I haven’t done for a very long time. . . . And thanks for “syuzhet,” which I intend to deploy at the first opportunity in my next Scrabble or Bananagram game.