When an artist knows they are about to retire, the last work they release becomes both a bequest and a memorial. Final works can’t help taking on a special tone—perhaps it’s a charge that surpasses reality, or a meditation on old age and mortality, or a monument to the artist’s ultimate artistic concerns. Isao Takahata, the co-founder of Studio Ghibli, was approaching his mid-seventies when he embarked upon his final film. Yet The Tale of the Princess Kaguya holds a unique space in the realm of a director’s final work because the story is not original—it dates back to a tenth century monogatari considered to be the oldest extant Japanese folktale.

Beauty, impermanence, and sorrow were recurring themes in the director’s oeuvre, always explored alongside a fascination with the nuances and fleeting moments of everyday life. For his final work, Takahata revived the story of the eponymous Kaguya. The film immerses us in childhood wonder, reveals the burden for women to be “beautiful,” and finally confronts us with the joy and sorrow of living.

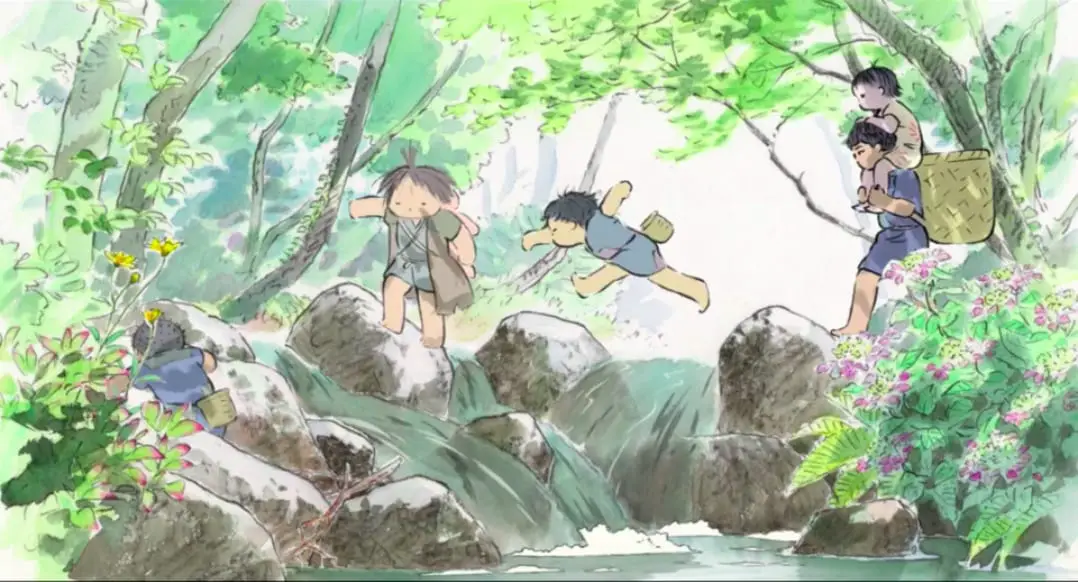

Bucolic Childhood

A farmer finds Kaguya as a tiny glowing creature nestled in a bamboo stalk. The farmer takes her home, where she turns into a human baby that he and his wife raise. Kaguya grows swiftly, becoming a young woman in a matter of weeks, and enthralling all around her with her elegance and ethereality. She displays a love of nature and a dedication to Sutemaru and her other friends, who call her “little bamboo” for the speed at which she grows. She plays with wild baby boars and jumps off cliffs into the river. Her high-spirited youth thrives in the pastoral setting, and she makes up a song that returns as a refrain throughout her life:

Go ’round come ’round distant time

Come ’round oh distant time

Come ’round call back my heart

Come ’round call back my heart

Birds, bugs, beasts

Grass, flowers, and trees

Teach people how to feel

If I hear that you pine for me

I will want to return to you

I will want to return to you

All is well until her father comes to believe she’s destined for life as a princess, as he continues to find fine robes and gold in the forest from which she came. Her parents decide to move to the capital, forcing Kaguya to leave behind her life and friends in the countryside. As a princess, her life quickly changes as her governess tries to tame her free-spirited nature. Donning a face of makeup for the first time, Kaguya asks how she’ll be able to laugh or cry or scream. Her governess says a noble princess never does those things, and Kaguya counters that a noble princess is not human.

Her governess insists that she not just act, but also look like a noble princess, revealing that the qualities that are considered beautiful are only symbolic extensions of desirable female behavior. In other words, for Kaguya to please her family and be accepted by the nobility, she must not only change her appearance, but also her behavior. It quickly becomes apparent that something important is at stake that has to do with the relationship between female liberation and female beauty.

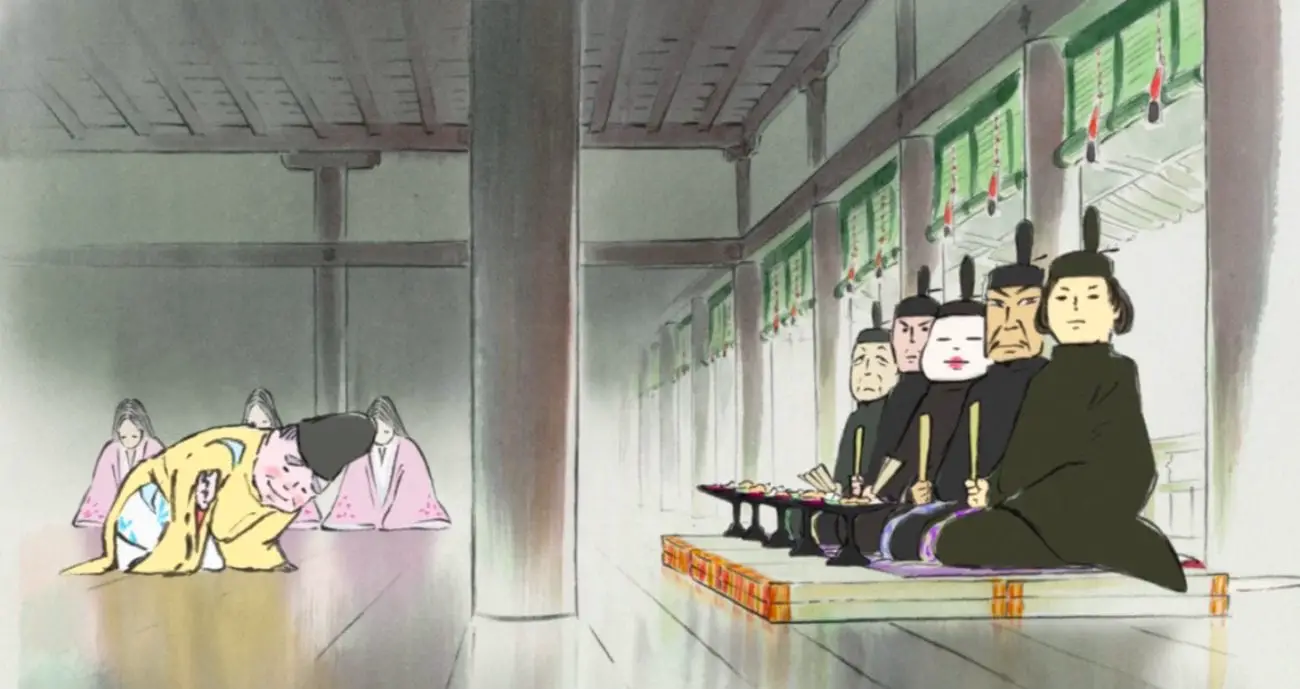

Emotion in Abstraction

When her father throws a celebration in honor of her coming of age, Kaguya overhears male guests criticizing her for not showing her face (although her anonymity is custom). They speculate that she looks like some kind of goblin, or worse. At this moment it’s apparent that although Kaguya has given up her entire life to move to the capital, she will now be trapped by the system her father would like her to join. To be a woman in this environment is to be already damaged, to be under scrutiny, to be in many ways less than human.

Princess Kaguya was in production for eight years, largely because it was entirely hand-drawn with charcoal strokes and redolent watercolor, evoking Japanese woodblock and scroll art (which would have been used to tell the original story). Because of Takahata’s refusal to use cel animation, insisting instead on a hand-drawn film, he reverted to a style that emphasizes emotion over detail, stating: “When you’re drawing fast, there’s passion. With a carefully finished drawing, that passion gets lost. I think that’s a shame,” Takahata wanted to emote the raw passion of visual art that can be worn away as an artist refines their work, thereby allowing the characters to embody their emotions through abstraction.

This is why the animation decomposes when Kaguya flees the house and the capital city after overhearing the guests’ criticism. Her despair comes through in the disintegration of the drawings. The deceptively simple imagery evokes her pain, as quite literally we see her world falling apart. When she stops running, she has returned to her mountain home, seeking Sutemaru and the rest of her friends. But she learns that they have moved away, and a stranger explains that they couldn’t harvest the whole mountain, or the forest would never grow back. That it needs ten years to heal. Perhaps the mountain, like Kaguya, does not have the capacity to give endlessly. There must be some give and take, and a compassion for their true natures, for them to remain. Kaguya passes out in the snow and wakes up back at the celebration.

The False Promise of “Beauty”

The story never seems to imply that the elements that suppress Kaguya stem from one individual. Instead, the root of her unhappiness comes from larger elements at play: men’s institutions and institutional power. Her parents brought her to the capital in order to give her a life she “deserves.” They do not see that this status-seeking binds them all in a reductive value system. No amount of money or beauty will ever be enough to make them happy, because money and beauty have nothing to do with real-life values.

Yet after this party, something changes in Kaguya. Her inability to find her friends inhibited something in her she needed to live, and gave her the ultimate sedative: no hope for escape. After the celebration, she completes her lessons quietly and obeys her governess. The film aches with a poignant melancholy for her previous life in the mountains as Kaguya retreats into submission. It is not until five noblemen show up asking for her hand in marriage that, in an act of self-preservation, she begins her manipulative games. She still has the power of refusal.

The noblemen desire to marry Kaguya after hearing she is beautiful, and in declaring their love to her, they compare her to mythical treasures across the country. The people around Kaguya believe this quality of “beauty’ objectively and universally exists, and that she inhabits it—even those who, like the men asking for her hand in marriage, have never seen her. They assume she must want to embody beauty, since the noblemen naturally want to possess her as a woman who embodies it. The pairing of the older rich men with the young, “beautiful” Kaguya is taken to be somehow inevitable—by her father, by her governess, by the noblemen. Only her mother displays a vague understanding of Kaguya’s pain.

Kaguya asks the noblemen to prove their dedication by attaining the mythical treasures they compared her to. It is her sly way of rejecting them, as she knows they do not—they cannot—love her for herself alone. Her governess quits, knowing this family is doomed if their daughter won’t submit to her feminine role, that her beauty will eventually be taken away from her (because it is something that is given to her by men) as punishment. The family does not hear from the prospective suitors for three years.

Then Prince Kuramochi brings back a jeweled branch of Mount Horai. While he presents the branch, artisans show up asking for payment for having made it. Kaguya laughs, relieved to be freed of her obligation of marriage. The Minister of the Right then arrives, claiming to have a fire-rat fur robe, and she suggests putting it in the fire to test his veracity. When it burns, he blames her for losing him his fortune.

Plucked From the Field and Thrown Away

Her handmaid wonders how much they spent to make the fakes, and Kaguya responds, “I’m sure that’s all I am to those gentlemen. I’m a fake jeweled branch, or a fire-rat fur robe that turns to ashes.” She recognizes that while “beautiful” women may be briefly at the apex of this system, it is far from the divine state of grace the men propagate. The pleasure of turning oneself into a living art object is a type of power, but a power in short supply, especially since aging is considered ugly. Beauty therefore dissolves with time, and cannot compare to the pleasure of living freely in one’s body, or the delight in shedding self-consciousness and showing emotions, or the reward of living off the land in the country, or the absolute liberation in turning one’s back on outdated ties between matrimony and objectification.

When her third would-be suitor brings her a regular flower, he claims to have chosen it because her beauty is of nature. He wishes to live as the flowers do in the fields, to leave the loud city and its formalities. But when the screen rises, the man’s wife sits behind the screen, and she says she would love to be taken away, as she desired when he said those very words to her so long ago. “Would she have been just like all the others?” She asks him. “Plucked from the field like a flower, and then thrown away? How many more princesses will be forced to shave their heads and go into a nunnery?”

The women—Kaguya, her mother, the noble man’s wife—all seem to understand what “beauty” really involves: the attention of men they do not know, rewards for things they did not earn, sex from men who reach for them as a jewel to be discarded after use, cruel aging, and a struggle for identity. They know, too, that the good things about so-called “beauty,” including the promise of security, of sexuality, of confidence, are qualities that have nothing to do with “beauty.” The women refuse to be rivals or instruments to an institution that depends on male dominance.

Finally, The Emperor of Japan calls upon Kaguya to be his wife. Her father is excited by the prospect of becoming a court official; his wife scolds him, saying he still does not understand how his daughter feels. “For a girl born in this land, there is no greater happiness than joining His Majesty in holy wedlock,” he argues. Kaguya turns to him, entirely calm, and says, “Papa if your happiness depends on wearing the cap of a court official, then I will go to His Majesty as you wish. And after you’ve put on that cap as part of the court, I will kill myself.” He looks at his wife, stunned. His wife glares at him.

His Majesty finds her refusal intriguing and decides to “grace them with a surprise visit.” Kaguya is practicing the koto when he arrives. He approaches her from behind and grabs her, saying his embrace pleases all women. He begins to drag her in order to take her to his palace when she turns invisible, running out of his grasp. When he cannot find her, he apologizes, and says he will withdraw for today, adding, “However, I believe your ultimate happiness lies in you becoming mine.” Kaguya’s series of suitors reminds us of man’s propensity towards ownership of women, particularly those they deem beautiful. Each of these men in turn represent institutions of control, and are convinced that Kaguya is an object in their collection for political and monetary gain.

The Paradise of the Moon

Her father was not wrong to have his daughter to lead a life of leisure and royalty—do we not all want what’s best for our children? However, the longer Kaguya spends in the capital, the further her melancholy extends. She spends each night in the Pavillion, gazing at the moon, and stops spinning or tending to her plants. When her parents ask what’s wrong, she cries in her mother’s arms and confesses that the moon put her in the bamboo. That she understood it the day His Majesty arrived. It was then, yearning for escape, unable to return to the idyll of the countryside, that she begged the paradise of the moon to take her back. Her people were coming for her.

Her father asks why she would leave them when everything they’ve done has been for her happiness. “All this happiness that you wished for me has been very hard to bear,” she confesses. Kaguya looks back on her life with the clarity of one facing her death. She recognizes, when she’s forced to go back to the moon, why she escaped to come to Earth, and where she learned the song that has always been in her heart. On the moon, there is no grief or sadness. But one woman before her had left, and Kaguya found her singing a mysterious song (if I hear that you pine for me, I will want to return to you), tears falling from her face.

“I had to know what those feelings from Earth were,” she tells her parents. “That’s why I broke the rules to come to this place. I wanted to know all the same things she felt, and now I know exactly what she was feeling as she looked back at this land. She wanted to come back here to feel all those wonderful, mysterious things again. I know it.” Kaguya knows now that she came to experience life, to live with the birds, bugs, and beasts. She found the world to be much more complicated than she anticipated.

Her father cries, saying he will not let her go, that he has loved her as his own since the day he found her. He was only another victim of the myth of Kaguya’s “beauty.” He truly thought he did what was best for her, even though he ripped her from her pastoral upbringing.

The Beauty of Impermanence

Kaguya’s mother has her handmaid prepare a carriage for her to return to the mountains one last time. There, Kaguya finds Sutemaru, who is married with a child. She gets her chance to tell him that all this time she had yearned to return, that with him she would have been truly happy. Sutemaru tells her to run away with him, and the two fly through the air, connected by their awe of each other and the earth. Then Kaguya sees the moon and gasps, asking to stay longer in order “to feel the joy and happiness of living on this Earth.” She falls into the ocean, and Sutemaru wakes up back in the field, thinking it was a dream. He’ll never know that Kaguya sought him out.

When the people of the moon return for Kaguya, her parents beg her not to leave. She holds them, crying, asking them to forgive her. An attendant from the moon assures her that once she dons the robe, her heavy heart will no longer trouble her, that “the memory of this impure earth will lift from her mind forever.” The attendant puts the robe on her shoulders, and her face stills. She goes with her people back to the moon. Her parents remain, crying, calling out, “forgive me.” Each begs the other to understand their actions: Kaguya wants her parents to understand that it is not them she asked to leave, but the burden of living as a woman in the capital. And her parents want her to understand that had they known their actions would cost them their daughter, they never would have taken her out of the country.

Kaguya, miles from the Earth, turns around. Tears brim in her eyes. We can’t help but wonder how her life may have turned out had she never been brought to the capital, had her heart never begged for escape. She knows that while there may be grief and sorrow on Earth, there is also joy and happiness. That all who live on Earth experience them in different shades, and all feel compassion.

We can understand The Tale of the Princess Kaguya with a small bit of wisdom Takahata left us with: “The earth is a good place, not because there is eternity. All must come to an end in death. But in a cycle, repeated over and over, there will always be those who come after us.” Takahata, in his final film, wanted us to know that while death is inevitable, there is also beauty in life’s impermanence. Like Kaguya, we do not have eternity here, and must savor this time.

In the end, because Kaguya insists on her desire to remain despite experiencing so much sorrow at the hands of her so-called “beauty,” she teaches us that though there may be pain in this world, we must appreciate the time we have with our family, the birds, the bugs, and the beasts. Because whatever comes after, even if it is free of grief, it cannot outweigh the joy and happiness of everyday life. She shows us that to be free in our bodies is the ultimate truth, because if in death you hear the world pines for you, you will want to return.

Wonderful synopsis – that has plumbed the depths of the movie

Thank you for sharing