Ever so quietly, Rick Alverson is carving out a special niche for himself in the sprawling landscape of contemporary auteurs. His knack for compounding scathing critiques of American pathology with the provocative techniques of a disruptive style of filmmaking is trenchantly calibrated. In each of the four feature films that he released over the course of the last decade—New Jerusalem (2011), The Comedy (2012), Entertainment (2015), and The Mountain (2018)—Alverson has exhibited an equal amount of directorial daring, aesthetic decisiveness, and philosophical astuteness. His slippery narratives may be oblique at times, and his abrasive characters may persistently emanate obnoxiousness, but his acerbic concepts are consistently incisive: piercing the viewer with a sense of disquietude. Watching an Alverson film is rarely comfortable, and that is precisely the point.

Given the incendiary undertones of Alverson’s films—unafraid to prod audiences in the same vein that Harmony Korine, Yorgos Lanthimos, Michael Haneke, or Lars Von Trier might—it is not surprising that his enfant terrible approach has been wildly polarizing. Not nearly as laconic as Tye Sheridan’s characters tend to be in his films, Alverson has repeatedly snapped back at the backlash he often receives, even going so far as critiquing critics. In perhaps his most pointedly tense rebuttal, he went after A.O. Scott’s The New York Times review for interpreting The Comedy as what he perceived to be willfully obtuse and jejune terms. A.O. Scott’s distaste of that film fixated on Alverson’s “passive-aggressive” inability to take “critic distance from its [vulgar] subject.” For Scott, the fact that the lead character’s “racist, homophobic and misogynist rants are delivered” without “evident irony”—and emerge from a place of entitlement—was unacceptable.

The ironic part of A.O. Scott’s scrupulous reproach was that by examining the ethical dimensions of The Comedy, he inadvertently illustrated Alverson’s main argument; Scott proved that even when an artist maintains an impartial distance from their subject matter, society can sovereignly derive cogent and autonomous moral conclusions. As Roland Barthes famously pointed out, the author’s original intentions are historically less integral to a work of art than its social and interpretive implications.

The response that naturally spawned from A.O. Scott’s dismissive critique revolved primarily around the notion of artistic ambiguity—namely, whether or not it was an artist’s responsibility to coddle and pander to the moral status quo. When Alverson finally spoke out, he repudiated what he viewed as Scott’s philistine suggestion to pad the aberrant misbehavior of the film’s lead character with infantilizing gestures of overt condemnation. In a multi–tweet invective, Alverson vehemently defended his neutral stance to the nihilistic lead of The Comedy—a deplorably apathetic, insensitive, and caustically aloof character named Swanson (played Tim Heidecker)—by saying “To question a filmmaker’s moral compass because he/she won’t submit to banal, cinematic moral grandstanding […] reduces the potential of cinema to a narrow, sanitized, puritanical and unreal world without potency…little more than a narcotic.”

In many ways, this fiery rebuttal of A.O. Scott demarcated what would become the central battleground of Alverson’s young career—a phase defined by his frustrations with a zeitgeist that disavowed art that was courageous enough to force its audience to tease out characters and narratives of ethical dubiety. Confronted by a fragile culture that easily cried foul play at any art that even ostensibly granted hypothetical licensure to social transgression, Alverson’s refusal to insert token signifiers of judgment or moral jaundice was viewed by many as dangerously stoking the perverse ideological embers of a largely invisible, imaginary, and yet inflammatory demographic.

The negative feedback that Alverson received for The Comedy was in no way limited to A.O. Scott. In his review for New Jerusalem—a film about the relationship between a National Guard vet (Colm O’Leary) and his concerned evangelical (Will Oldham) coworker at a used tire store—Roger Ebert compared the nascent auteur’s first two feature films in stark polarities: “The two films could not be less alike. One vulgar and heartless […] this one, so quiet and sad.” Though less decisive in his distaste of The Comedy, it is pretty apparent that Ebert, like Scott, found it similarly repugnant and bereft of any edification.

Alverson’s third film, Entertainment, would in many ways up the ante on this cultural squabble: aggressively goading critics by releasing what David Edelstein called in his Vulture review “one of the most pretentious, pointlessly grating movies ever made.” Asserting that Alverson shocks for no good reason, Edelstein went on to bemoan the “stunted, disagreeable little man”—an acidic, nasal-voiced stand-up comic named Neil Hamburger, played to perfection by Gregg Turkington—at the center of the film: “Neil becomes the vehicle for examining the skeletal remains of a snobbish, viciously exploitative America.” Edelstein, for what it is worth, grappled at length with Entertainment. With self-effacing honesty, he even re-watched it to test the possibility that his “bourgeois expectations of comfort” were the impetus for loathing what might be “an authentically punk art movie”—only to come to the conclusion that “Entertainment wears its contempt too arrogantly, fulsome in its emptiness.”

Edelstein’s focus on Alverson’s tonal excesses is a much more valid take. Though Alverson’s vision is sharply—even brilliantly—satiric for anyone on the same wavelength, his iconoclastic antics in The Comedy and Entertainment mined an absurdist, intentionally alienating humor that veered superciliously. Sure, Alverson’s subversively shocking and sour antics within those films held nuanced motives and deeply considered aims, but it is also difficult to deny that these films’ insistently confrontational flirtation with taboo topics did not reveal Alverson’s predilections for veering uncomfortably and recurrently close to a specific brand of hipster snobbishness, coded in postmodern mockery, buffoonery, and elusiveness.

Regardless of how highbrow and complex the underlying objectives may have been, Alverson’s patronizing posture and his juvenile inclinations to titillate audiences with a sophomoric type of arthouse trolling were justly divisive. Thus, to those that found his barbed cinematic gimmickry to be callow, off-putting, and haughty, there was little left to defend—even for the most outspoken Alverson apologists. On this point, debates about the value of Alverson’s work become more a matter of taste than ethical or intellectual fortitude. One thing became glaringly clear: Alverson needed to transcend his comfort zone.

This is why Alverson’s creative detour with The Mountain is such a resounding triumph. Muted and mystifying, Alverson’s latest may be his peak achievement thus far. While still darkly antisocial and aesthetically distancing on a stylistic level, The Mountain is a much more mature vision devoid of the crass, man-child tomfoolery that pervaded his previous works. Structurally, the film largely abides by the tropes of a classic road trip narrative: following Dr. Wallace Fiennese (Jeff Goldblum), a lobotomist, and Andy (Tye Sheridan), the young photographer he hires, as they cross the country from one insane asylum to the next.

Spare in its reliance on exposition and often glacially paced, the film at times feels thinly held together. This is by design. As Chris Pomorski points out in a 2019 profile piece on Rick Alverson in The Ringer, Alverson is painstakingly dedicated to minimal, non-verbal storytelling. Even his co-writer Dustin Guy Dufa’s expressed a mixture of awe and annoyance at his commitment to expository terseness: “Rick wants the very minimum amount of information you can use and still have the story operate […] he’s to the extreme.” Yet, as Pomorski chimes in, “[in] failing to sufficiently orient the audience, [Alverson] risk[s] compromising the film’s architecture.”

Luckily, even when The Mountain’s taciturn and meandering narrative boldly defies conventional pleasures, the film is persistently engrossing. Between the film’s charismatically enigmatic cast, meticulous attention to detail, idiosyncratic visual acumen, and the brooding dread lurking behind the period piece veneer, the frigidly formalist picture tethers you along. From the first shot—a slow-motion aerial view of an ice skater spinning—to the lustrous widescreen shots of the vintage 50s cruiser ascending an alpine highway to the cryptic final image, The Mountain is endlessly refulgent.

The film is utterly transfixing to behold, eclipsing the visual vocabulary of his earlier work. It thus makes sense that when speaking on his directorial priorities with The Mountain, Alverson commented on his preference for form over content: “I’m concerned with intonation, body language, blocking. Once you begin to focus on those elements, you can become consumed by minutiae—something happening in the corner of a frame, a single lighting fixture.” Evoking German Expressionism, the emotional clarity and visual intensity of a spellbinding Paul Thomas Anderson sequence, and the symmetrical compositions of a Wes Anderson tableau, The Mountain is steeped in exquisitely, punctiliously, constructed dioramas.

Moving from the micro to the macro—or from the specific to the general—is a good way to approach The Mountain. Allegorical in its scope and literary in its use of motifs, Alverson composes each mise-en-scène with such delicacy that the subtle arrangements and minor gesticulations speak volumes, even when the characters on screen are icily mute. This becomes essential given that Andy, the terminally passive and unspeaking photographer/protagonist, is our only true window into the unforthcoming worldview of this purposefully opaque film. Offering a lens within the lens—a detached and observational portal internalized within the context of the film—Andy’s silent horror mirrors our own, even as his face remains stolid and expressionless throughout.

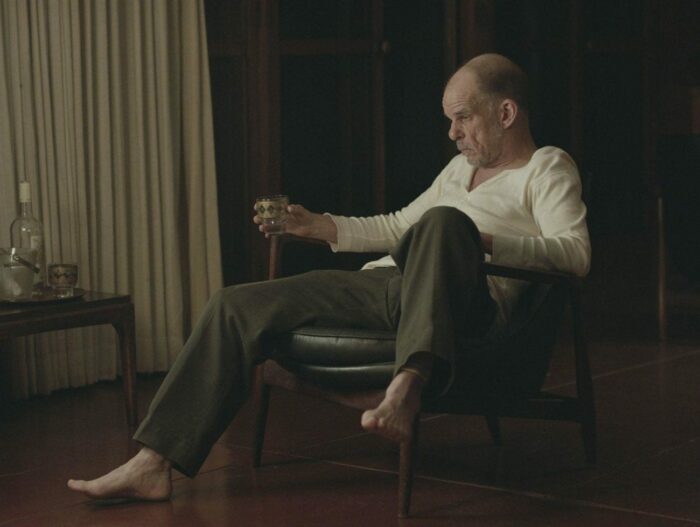

Wherever Andy turns, he is haunted by toxic male figures. His father Frederick (Udo Kier) reigns over the ice rink with a phlegmatic yet iron fist until he suddenly keels over on the ice and dies. Recruited by the womanizing and pitiless Dr. Fiennes, Andy subsequently finds himself shadowing another patriarch with a truly sinister cavalier disregard for the patients whose prefrontal lobes he penetrates with an icepick scalpel. Finally, when Dr. Fiennes lobotomizes Andy after the latter explodes in a harrowing paroxysm of pent-up anger—slamming wooden chairs into pieces along the corridor of a mental asylum—the cognitively dulled young man is dropped off at the remote Mount Shasta home of the also lobotomized Susan (Hannah Gross) and her manic dad Jack (Denis Lavant).

Jack—a Frenchman who drinks like a madman and works as a New Age musical therapist—is the most outspoken patriarch we witness torturing and tormenting Andy’s already submissive demeanor into a state of total terror and abject resignation. In what is by far the standout scene of a film that offers many, Jack harangues Andy for having praised a cheap, mass-replicated painting hanging above the sofa in Jack’s home. “They’re a dime a dozen,” Jack shouts, aghast at Andy’s boorish, uncultured comment. “You look confused. What confused you?” Andy does not respond—as is customary for his character—standing stoic, still, and benumbed in the face of the ensuing tirade. Jack proceeds to lecture him about art: “Art is a thought for which there is no other form in the whole wide world. That’s not a mountain! That’s a picture!”

Irate and filled with disdain, Jack’s words feel more aimed at the standard American moviegoer than they are at Andy—our surrogate proxy. This is perhaps why Jack appropriately enough ends his polemic with a direct critique of America itself: “Americans… you are a precious race. Precious and free!” he disparages, with acrimonious sarcasm. It is hard to not infer this as anything other than Alverson breaking the fourth wall, boldly ridiculing his already weary audience.

Though it’s a somewhat contrived postmodern cliché Jack breaks the fourth wall in a way that somehow transcends the technique’s petty ambitions to belittle the defenseless. As unfair as Jack’s outburst is, the broadside offers a perfectly impromptu manifesto for the film, which keenly concludes with Andy and Susan driving a snowy, serpentine road toward the tip of another mountain. Shivering and gazing at the snowy summit, the film’s final shot hones in on Andy, dumbly enthralled by the mountain’s majestic peak. The audience is kept equally frigid, and left to wonder—are we staring at a mountain or a picture, or a synthesis of the two?

Given Jack’s spontaneous broadsides about art and reality earlier in the film, it seems that Alverson would favor the notion that we are staring at artifice. In a film dominated by characters that lamely consent to the horrors of misguided medical procedures, blindly yield to the horrors of the patriarchy, and docilely abide by the scruples of psychological institutions, the exaltation of a romanticized pinnacle makes sense. Mountains are pyramidal by nature: resembling a hierarchy. Similarly, the 1950s were an age marked by rigid social strata, delineated by gender and the ability to conform. It was a decade of deferential reticence and exacting verbosity, oppressive acquiescence and colonialist rationality—with a middle-class, conformist society collectively donning the stultifying ideals of superficial normalcy. It was also a decade of latent, unspoken madness and insanity: of mind-numbing, tongue-tying compliance. And in such restricted air space, the marvelous power of art becomes the only conduit left for the ineffable and the silenced to escape and communicate.