Directed by the Farrelly Brothers at the peak of their popularity, Kingpin’s bawdy humor fits their sensibilities (see Dumb and Dumber and There’s Something About Mary) so perfectly it is a shock to learn that they did not write the screenplay. Raunchy, ribald, and yet intermittently warm-hearted, the movie is clearly a collective effort—the byproduct of a comedic team who are all tapped into the same juvenile wavelength. Written by Barry Farano (who also penned Men in Black II and I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry) and Mort Nathan (who directed National Lampoon’s Van Wilder: The Rise of Taj and Boat Trip), Kingpin follows the life of Roy Munson (Woody Harrelson), a bowling prodigy from small-town Ocelot, Iowa who heads out on a nationwide professional bowling circuit after winning the 1979 Iowa State championship.

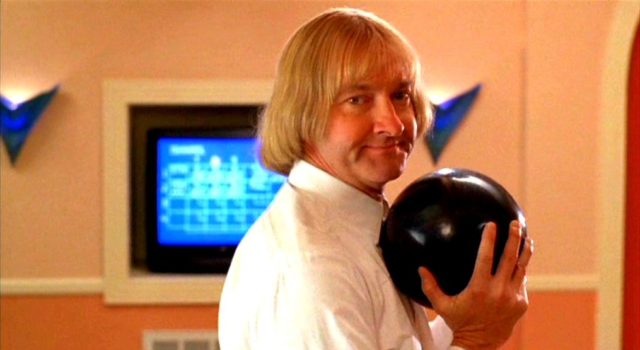

Unfortunately, Roy’s naïvety quickly lands him in trouble. It doesn’t take long before he is lured into a racket with Ernie McCracken (Bill Murray), a bowling rival who recruits Roy as a sidekick to his schemes. In what turns out to be a life-changing grift, Roy’s role is to pretend to be incompetent during a bowling match with money on the line. The hustle—feigning amateurish talent to coax a competitor into betting big—very much feels like a nod to The Hustler (a much classier sports movie). The ploy pays off (at least at first) when Munson knocks down a 7-10 split, winning Ernie and himself some quick money. Not long afterward, the two men are confronted in the parking lot, and Ernie—being the selfish and spineless traitor that he is—ditches Roy by peeling off in his beat-up car. Left to fend for himself, Roy is beaten savagely by the men he and Bernie had just conned in a violent montage that ends with Roy’s hand being thrust into a bowling ball return and severed.

With this fast-paced opening, Kingpin swiftly treats its audience to a vintage ‘90s Bill Murray performance (mixing sleaze and charm like no other), not to mention a fun and dialed-up Woody Harrelson outing. The opening scene of the film is one of the most extravagant in the Farrelly’s oeuvre. Presenting Roy as a big-shot bowling wunderkind, the camera tracks his stylish arrival at a state bowling competition: capturing the uproar of a frenzied crowd, the jubilant disco vibes, and the sexy big-breasted (a very intentional attribute) women in groovy bell-bottoms all dancing in unison. The ecstatic aura around Roy is pulsing and palpable. It is Saturday Night Fever, only set in a rundown bowling alley in middle of nowhere America.

The festive atmosphere, contrasted by the drab setting of the charmingly old-fashioned bowling alley, easily brings to mind the Coen Brother’s timelessly flamboyant bowling alley spectacles in The Big Lebowski. Cheekily choreographed, this introduction of Roy serves two functions. First, it humorously exaggerates the stakes of the state bowling tournament. Second, it showcases the prodigious fame and idol-worship Roy had garnered amongst his provincial community. Thus, when we see Roy lose his hand just a few scenes later, the heightened gravitas of the tragic amputation is immediately registered. His cartoonish and drastic downfall from a bowling virtuoso to a handicapped victim is so jarring and steeped in hyperbolic bathos, the ridiculousness of the contrast evokes a chuckle.

This backstory is merely a prologue to the film. Cutting 17 years later to the present day, the Roy we are reacquainted with is a pitiable figure. Sporting a prosthetic hand that reminds one of Happy Gilmore’s Chubbs Peterson, he is now scraping by as an alcoholic, balding, petty thief in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Constantly behind on rent, he survives off various hustles. Roy has become a stereotypical washed-up lowlife: a has-been just like Ernie. He is such a loser that he hires someone to steal the purse of his nagging, yellow-teethed landlady Mrs. Dumars. The theft is a ruse staged for Roy to swoop in, valiantly defend Mrs. Dumars, and heroically return her belongings. He is temporarily successful until Mrs. Dumars enters his apartment the very moment he is paying the purse-snatching accomplice. To avoid eviction, Roy is forced to perform cunnilingus on the haggard old lady to pay off his back-rent (a gesture merely insinuated by a shot of Roy puking and hugging a toilet Ace Ventura-style). Narratively, he has hit rock bottom.

Soon thereafter, his fortunes take an upward turn. Roy catches a whiff of a local bowling talent while peddling condoms to the manager of a local bowling alley. The talent turns out to be an Amish man named Ishmael Boorg (Randy Quaid). Without any hesitation, he proceeds to solicit himself as a successful sports agent and proceeds to weasel his way into the local Amish community. Roy is ill-fit for the Amish lifestyle, and Ishmael is wisely standoffish at first; but when news that the bank is trying to repossess his family’s farm breaks, he acquiesces to Roy’s insistence that they head out to Reno, Nevada, to participate in a million-dollar winner-takes-all tournament.

From here on out, the narrative beats align with your run-of-the-mill buddy road trip movie—which is certainly familiar territory for the Farrelly Brothers. All five of the duo’s iconic ‘90s feature films revolve around road trips, either originating in rural Rhode Island or Pennsylvania. Each of these films also serve as narrative vehicles that allow physically, cognitively, psychologically, and/or emotionally impaired characters to find their way. Whether dimwitted (Dumb and Dumber), schizoid/psychotic (Me, Myself & Irene), feigned disability (There’s Something About Mary), perennially stoned (Outside Providence), or physically disabled (Kingpin), the Farrelly Brothers filmography is filled with quirky and oddball ensembles crisscrossing the country and navigating life.

The Farrelly Brothers’ commitment to both embarrass and stick up for pariahs, idiot savants, and disabled peoples is inarguably the definitive feature of their career. As a consequence, their films have been rigorously debated with critics drawing strict lines on whether or not they charitably or uncharitably depict characters like Lloyd Christmas and Ishmael Boorg. Some find these figures to be mere caricatures exploited for the sake of humor. To others, they are sympathetic protagonists portrayed with a redemptive degree of dignity.

For what it is worth, the Farrelly Brothers’ ardently claim to be champions of the characters they put on screen. They claim to staunchly refuse to pander to formulaic stereotypes and categories due to their reverence of outcasts (i.e. the boorish working-class, the disabled, the slacker, the mentally insane, the theft). Instead of writing idiots, losers, and handicapped individuals as victims that audiences should pity, belittle, or piously admire as resilient angels, Peter and Bobby’s primary goal has been to treat such characters no differently than regular people.

In doing so, they have daringly entered dangerous comedic and ethical territory film after film. Sometimes, it gets them into trouble. However, in response to critiques about their supposed “ugly stereotypes” and lampooning of disabled, handicapped, and doltish characters, they vigorously defend their characterizations. As they see it, their films neither snub nor disparage these prototypes. Quite the opposite, they believe their films positively reshape public perceptions of marginalized/disabled peoples.

In a 2012 interview with Ability Magazine, Peter even notes, “The definition of cool or what’s acceptable is constantly changing[, but] until someone breaks the mold and shows us something differently and makes that which once seemed like a weakness into a strength, we’ll keep our misperceptions.” This, if anything, is the sole topic/subject for which the Farrelly Brothers films offer intrigue. Self-defined flag-bearers for the handicapped, both Peter and Bobby adamantly argue that they venerate disabled peoples and purposely portray them as ordinary/ flawed out of respect. Tired of unrealistic and idealized “syrupy, saint-like representations” of handicapped people in the media, they claim to intentionally depict ‘disabled’ characters with complex and ambivalent qualities to normalize them. Instead of elevating disabled characters to an impossibly lofty and remote pedestal, their goal is to make these characters multivalent and relatable. Somewhat ironically, they claim that by making marginalized stereotypes into regular Joe’s, their representations are more inclusive.

In Kingpin, this stance rings true. Roy may be physically disabled (with his prosthetic hand) and Ishmael may be a fish out of water (as an Amish man traveling across the country by car), but neither are mocked. Sure, they are both the butt of many jokes and endure humiliating moments; but the film fully respects their humanity and value, and this overpowers the moments it pokes fun of them. By letting Roy and Ishmael be dynamically sweet and sour, ordinary and exceptional, goofy and serious, Kingpin becomes a more-rounded and likable film.

This very balancing act also establishes the Farrelly Brothers as great storytellers in the carnivalesque tradition. By flaunting what is vulgar, vaudevillian, and unseemly, they inversely promote the essential humanities inherent in taboos. In proudly accentuating the shared improprieties and essential obscenities of the human body (i.e., the fact that we all puke, sh*t, fart, and piss), their films subversively flatten our false dichotomies and hierarchies. Filled with silly comedic gags, the Farrelly Brothers’ films remind us that we are more alike than different, despite belonging to various groups, categories, classes, and ranks.

About halfway into Roy and Ishmael’s journey, a somewhat predictable third wheel is introduced: a conventional ‘90s hottie named Claudia (Vanessa Angel). Claudia serves a role not unlike Mary (Cameron Diaz) in There’s Something About Mary or Mary Swanson (Lauren Holly) in Dumb and Dumber. She is a princess in distress—a bombshell girlfriend of the wealthy asshole. In the world of Kingpin, this asshole is bowling enthusiast Stanley Osmanski. Ishmael beats Osmanski in a one-on-one bowling match on his mansion’s private bowling lane. Afterwards, Claudia escapes with Roy and Ishmael—fearful of being abused by her angry boyfriend, who had blamed her as the scapegoat (for failing to effectively distract Ishmael during the 10th frame with her hardened nipples).

Fleeing the mansion with a quintessential 90s ska song blasting on the soundtrack, the getaway sequence is a trademark 90s moment. This song choice, in particular, Goldfinger’s “Superman,” is not only a staple of the era but also a signature Farrelly Brothers motif. As fans of power pop, rock, ska, and folk, they have consistently incorporated buoyant and memorable songs into their films. In Kingpin, we are treated not only with needle drops of ska bands like Goldfinger and Reel Big Fish, but cameos from Jonathan Richman of the Modern Lovers (playing in a dumpy bar), and Blues Traveler playing over the credits. These musical acts all belong to an eclectic range of genres, but they do share one thing in common: they are all unabashedly unique and anomalous commercial success stories. Clearly, even in selecting their film’s needle drops, the Farrelly Brothers seem to be keen on shining light on idiosyncratic artists.

With Claudia added to the mix, the film cues up every expected road trip scenario that results from this third element. We witness internecine fights about jealousies and ulterior motives, vacillations between interpersonal conflict and bonding, memorable restaurant stops, and lots of puerile sexual jokes. Eventually, the trio winds up in Reno, where Claudia is hunted down by Stanley (her controlling ex-boyfriend), and Ernie McCracken reappears (out of the blue): foreshadowing a sports movie showdown for the ages. As expected, Ishmael can’t bowl (in this case, he breaks his hand), leaving Roy to take his slot in the tournament out of sheer desperation—meaning that he’ll ostensibly be bowling with a prosthetic hand for the first time ever. Unbelievable as it sounds (and yet anticipated a mile away), Roy miraculously finds his touch again and ends up bowling so well (despite having a rubber hand and 20-plus years of athletic rust) that he makes it to a final showdown with McCracken (who is also somehow better than the competition, despite being so patently over-the-hill).

Rocking equally bad combovers, the dueling conmen and nemeses soon become the talk of the country (with Chris Berman narrating Sportscenter highlights on ESPN and everything). Appropriately enough (at least for a movie as subversive as this), Roy loses by one pin. To make matters more tragic, Roy actually blew a considerable lead on McCracken—completely collapsing once he noticed Ishmael (his sole confidant and good luck charm) being whisked away by his brother. Nevertheless, despite squandering the million-dollar tournament reward, Roy manages to score an endorsement deal with Trojan Condoms (by virtue, presumably, of the commercial appeal of his now famous rubber hand) and rakes in half-a-million on the side. Fortuitously, this also just so happens to be the exact amount of money needed to save Ishmael’s family farm. And thus the movie’s fairy tale ending arrives: with Claudia and Roy in love, Ishmael a savior, and Blues Traveler (dressed in Amish clothing) sacrilegiously playing an electric concert for the Pennsylvanian Amish community.

The fact that Claudia and Roy end up together at the end of Kingpin both 100% expected and preposterous at the same time. Claudia is young and gorgeous: a total 10 on the ’90s meter. Roy, meanwhile, is about as unattractive as Woody Harrelson could possibly be (without extensive prosthetics, cosmetics, or CGI). That said, the fact that they end up together is not simply to satisfy male moviegoers’ fantasies. There is very much a deeper, less superficial intent. In many ways, the budding romance between Claudia and Roy mirrors the Farrelly Brother’s 2001 film Shallow Hall, which tracked the transformation of Hal (Jack Black) after he is hypnotized by a guru and learns to appreciate inner beauty instead of fixating on perfection. The moral lesson here is generic, but also profound: reinforcing the fact that imperfection is merely a social construct. This moral nicely aligns with the Farrelly Brothers’ agenda to upheave classical social standards and preconceptions.

Light-hearted, goofy, and filled with outlandish twists and turns, Kingpin somehow manages to charm despite its gaucher, more repugnant moments. Most of all, it gets by on the merit of the motley misfits at the center of its story. Following a band of losers, victims, and outcasts from small-town America, not to mention a sport that itself is quite niche and marginalized, the film’s broad and prepubescent sense of humor may be hit-and-miss, but the idiosyncratic clan at the film’s center keep things fresh.

Roy gets the bulk of the indecorous laughs. We witness a fistfight with Claudia where he gets kicked square in the balls before punching Claudia’s protective breasts multiple times (with no success—they are too bouncy to injure). Roy is the butt of numerous gross-out sequences, such as when he drinks a pail of cow milk on Ishmael’s Amish farm, only to learn that they only rear bulls (think about it). We are treated to countless visual jokes involving his prosthetic rubber hand and fingers, including one where a failed bowling attempt ends up with his hand flying backward and landing on a stranger’s breast. And we must endure the aforementioned scene with his landlady, where Roy is hunched over a toilet bowl suffering from post-coital queasiness (the moment aided by an allusive use of Simon and Garfunkel to nod to The Graduate’s Mrs. Robinson).

Claudia, as the two-dimensional hot chick, gets a fair share of laughs as well. We meet her at her boyfriend Stanley’s mansion, where she is told to get drinks from a freezer, which make her nipples absurdly hard. Later, she employs a similar grift to help the trio scam their way toward Reno: salaciously distracting uncouth dudes bowling against Ishmael in matches that Roy has bet on. The punchline of this particular montage comes by way of an old fellow who is impervious to the charms of her cleavage and G-string (which Claudia reveals by strategically standing above the air vent on the ball return machine), but is turned on the livestock Roy brings in to disrupt the country bumpkins’ concentration (a subtle reference to his implied predilection for bestiality).

Ishmael is at the center of many risqué bits as well. In one verbal innuendo, he is hinted at as being on the receiving end of a hypothetical homosexual encounter with Roy (which coincides with a shot of Ishmael lying prostrate on a hotel bed). There is also a dramatic splitting up of the group in the third act. Feeling betrayed, Ishmael runs off and tries to hitchhike back to his Amish community, only to end up dancing on a stripper’s stage in drag (wearing nothing but a bra, a bikini, and high heels). Later, after Roy and Ishmael reunite, the two wage a prank war that culminates with Ishmael pouring shaving cream on Roy’s pirate hook (why he took off his prosthetic hand, we will never know) before rubbing his nose with a feather. And finally, there are the constant jokes about Ishmael learning the ways of modern life—from repulsively flossing his filthy teeth for the first time to getting a naughty tattoo that covers his whole torso.

The common thread between all these jejune antics, jabs, and callow comedic interludes is the motif of juvenilia. It is very much a mainstream ‘90s era comedy. Filled with boyish, elementary gags and oddball characters, Kingpin truly demands one be in the right mindset, but the same could be said for all the Farrelly brothers’ movies. From Ben Stiller getting ejaculate in his air and his nuts stuck in his zipper in There’s Something About Mary to the explosive diarrhea sequence in Dumber and Dumber to Hugh Jackman’s neck-testicles in “The Catch” segment of Movie 43, Peter and Bobby have unabashedly spent the past few decades making inappropriate comedies about kooky characters.

Where the Coen brothers aim high, the Farrelly brothers aim low. What salvages their films, however, is that they aim low with heart. Obsessed with silly puns, wild road trips, big breasts, slapstick/toilet humor, handicapped and mentally impaired subjects, themes of disability, it is quite clear that working in the realm of taboo is their modus operandi. The fact that Kingpin interweaves Amish culture (a technologically impoverished community), bowling (a sport of ordinary schlubs, a la The Big Lebowski), and end up in Reno (the poor man’s Vegas) makes perfect sense. Sure, it is a film that is intermittently grotesque and constantly nasty, but it ultimately celebrates its motley crew of hardscrabble deviants, low-rent fraudsters, and quirky mavericks as they eke it out just enough to survive amidst the lewdest wasteland of all—the detritus of American capitalism. With quixotic gambits, physical defects, and sportive ambitions, Roy never gives up. Above all else (even his rubber hand), that drive is perhaps his most distinctive characteristic. Like Roy—grubby, seamy, and well past his glory days—Kingpin’s cruder contours have not been treated extremely well by age and the tides of culture, but at the end of the day, they both have sizable hearts and clever enough grifts to woo over their captive audiences.