When it was released in 2013, the Ari Folman-directed film The Congress received very little fanfare. Sure, there were some excellent reviews and a number of prestigious European film awards were bestowed upon the film, but the general public seemed nonplussed. This was surprising, considering the technical achievements of the film’s brilliantly animated portion, the praise heaped on Folman’s previous film Waltz with Bashir (2008), and a well-known cast of character actors that consisted of Robin Wright, Harvey Keitel, Paul Giamatti, Jon Hamm (in voice only) and a turn from young upcoming actor Kodi Smit-McPhee. Yet, the story, adapted from Polish writer Stanisław Lem’s 1971 novel The Futurological Congress, is perhaps the most telling of why the film failed to make a connection with audiences. Nobody really wanted to hear about the negative aspects of the technological revolution that the internet had brought us, and the promised utopia of future technologies and virtual reality being a fool’s errand.

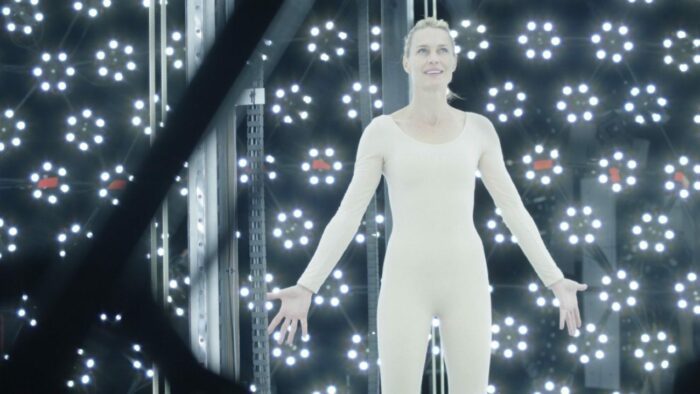

The Congress stars Robin Wright as a fictionalized version of herself. She is, in Hollywood’s terms at least, on the wrong side of 40, and with the prospect of her career winding down, she is offered the opportunity to sell a digital avatar of herself to Miramount Studios (a combination of Miramax and Paramount if you didn’t already guess) so they can insert her preserved digital self into all manner of film productions and commercials using a ‘deepfake’ style technology. Wright will never need to work again. Her digital avatar will pick up the slack while she can live her life away from the spotlight on the massive payout from Miramount.

Perhaps audiences didn’t take the premise of losing oneself to the fantastical as something of concern in 2013, yet The Congress is perhaps more relevant and timely today than it was just a few years ago. Despite its rather messy narrative structure, The Congress is the perfect film to understand the Post-Truth, Post-Trump era we seem to find ourselves in. Our societies have become deeply fragmented and divided into squabbling sub-realms of hard-right, hard-left, and inept centrists, whilst the most important thing now is the promotion of the individual and what the individual desires, society be damned. Even though the film was released in the social media era, The Congress seemed to know where we were heading and where we still might be heading. And it’s a dark place.

The internet and the rise of social media have played a part in the fragmenting of reality and society as a whole. It starts with us. We no longer present ourselves as just ourselves online, but some hyperreal version of what we consider to be our best aspects. Filters and framing are used to present this ‘unreal’ version of what we perceive our bodies and faces to look like, or how we want them to look to others. We haven’t landed in the completely fabricated worlds seen in The Congress, but we are certainly using our time on social media to distract from the reality of what is going on around us and further falling towards the digital realm as a replacement for reality.

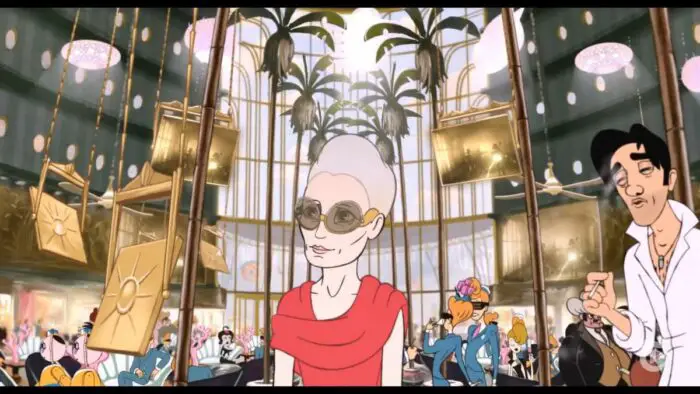

In the film, Wright attends an event called the Futurological Congress, a conference organized by Miramount in Abrahama City, a vast place where the surroundings and citizenry are completely animated in a kind of surreal cartoon hellscape that Wright herself describes as “Cinderella on heroin.” When it becomes clear that the massive conglomerate Miramount plans a massive program to allow every person across the globe access into these digitally animated worlds, Wright uses the opportunity to denounce the proposal, imploring the audience to “Wake up people wake up” from the nightmare and instead to direct the vast resources to means other than entertainment and distraction.

Whilst this is clearly intended as a wake-up call to the audience in attendance at the Futurological Congress, we should also see it as a call to the audience sitting at home (or in the limited cinemas this film was shown in) to take a deep look at where the world is heading in terms of the social media dominance of our time, but also the vast amounts of money and other resources spent on wars, and other wasteful ecologically damaging projects that governments and corporations deem essential to maintain our standard of life. As Wright is dragged away by Miramount’s goons, she screams that they/we will “die of guilt” if no action is taken soon. Guilt is certainly an emotion we are dealing with in our societies. The ecological destruction was something we were aware of and warned about decades ago, yet collectively we chose to ignore it thinking that a scientific solution was just on the horizon. That solution is not coming. As more and more destructive events occur across the globe, guilt and grief for the dying planet is something we will no doubt live to regret.

And while we ignore the turmoil the planet is in, we focus solely on our own images and personal ‘brand’. When Wright originally signs over her digital image, she is promised by Miramount’s CEO sleazeball that her physical features will revert back to a more pristine incarnation of her stardom. On-screen, she will forever be 34 years of age, never a day older. This is an obvious temptation for any of us.

The internet allows our lives to be preserved forever in the past. We can look back on ourselves as young and elegantly wasted twenty-somethings propping up a bar on New Year’s Eve, not a care in the world, but we never look at our present, and never to the future to understand what it might hold. The past is more beautiful. In one of the film’s animated dreamlike sequences, Wright and her companion Dylan, a friend who has helped her navigate the animated reality, fly above the cityscape while a song composed by Max Richter (with vocals performed by Wright) titled “Forever Young” plays on the soundtrack. While in reality, we age out of our looks and ‘hot bods’, the internet is where we can remain “Forever Young” and see and be reminded of our once happier existence.

There is also the small matter of consent when it comes to what The Congress represents in terms of ownership. Wright signs over her digital image with a clause that her avatar not be used in any demeaning way. No porn and no sci-fi genre films are what she demands. The sci-fi clause is eventually worked out of the contract, and in fact, her most popular post-deal role is the puerile sci-fi action entertainment franchise “Rebel Robot Robin”. This is funny because The Congress is clearly a piece of science fiction, a genre that the real Wright has mostly ignored, focusing more on performance-led turns in dramatic films such as The Crossing Guard (1995), The Pledge (2001), and Breaking and Entering (2006).

Nonetheless, the studio is free to disseminate Wright’s image, as they see fit. The idea of consent and privacy, at least for the digital self, is thrown out the window. And this happens to us as well. When we ourselves sign to a new social media network, the terms and conditions (which, let’s face it, we rarely read) usually allow for the plowing of our own images, videos, and posts. These snippets or swaths of information are compiled and analyzed by data companies and used against us in targeted advertisements whilst our watch history on YouTube takes us down a path that seems to lead to fake news outlets and extremist content. Anything to keep us hooked in and watching.

We like to think this is our free will taking the plunge and that our consent to watch these videos or a celebrity’s post on Twitter is our own, but the algorithms that lurk in the background of places like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, TikTok, and the internet as a whole direct us unknowingly to places we might not want to go, places that might be damaging for our mental health and that might even turn allies into enemies. Our own consent or “gift of choice”, as Wright puts it in The Congress is up for debate when we sign those terms and conditions and when we post images of ourselves online. Like Wright, we are also digitally owned.

The Congress made little impact when it was released, but people should absolutely be seeking it out now and hopefully pulling out a few lessons about truth, reality, and the hyper-digitalization of every aspect of our lives. Things were obviously bad in 2013, enough for the seeds of this film to come to fruition, but in the few short years since its release, the worst aspects of the internet have only accelerated, and with it, the worst aspects of humanity have risen to the top.

It could be argued that the manipulation of truth and reality that began on the internet and bled into the real world gave us a Trump presidency, pushed the United Kingdom out of the European Union, made climate change denialism a mainstream perspective, gave narratives of nationalism, racism, and anti-immigration sentiment legitimacy, made Covid-19 conspiracy theories something for debate on daytime television, and gave anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers a mainstream voice. All this, of course, existed long before the internet, but now, like the fake animated worlds of The Congress, we are living with the ‘alternative facts’ of a staged reality, or as stated in the film, we are “reinventing the truth” of the current world. All this is no longer on the margins of society, it’s our daily lives. And it’s really, really draining.

This is not meant as a denouncement of the internet or the social media networks which have connected millions and brought otherwise dispersed groups together to organize and take action against the disputed narratives listed above. We need this connection more than ever. Does it need more public oversight and better legislation? Do these massive conglomerates need breaking up and held up to accountability? Absolutely. The narratives cannot be set by a few billionaires. However, that would be an argument for another time.

There is also no harm in losing oneself to fantasy for a while. We all need a vacation away from the sometimes brutal nature of the world. Activities such as reading a book, playing a video game, watching a few YouTube videos, listening to a podcast, taking a walk in the park, having a swim, are all healthy and necessary. But, the customized realities we build for ourselves within the walls of the internet are slowly closing in and engulfing our everyday lives. We don’t just have an internal ideology anymore. Our very personality is defined by one.

The impacts of climate change on the real world are being ignored. When there is no telling what is reality and what isn’t, it’s easy to lose ourselves to fantasy because fantasy will always allow for delusion. But fantasy can only exist within the confines of a stable reality.

When Wright escapes the animated world after spending 20 years inside, she emerges into a grey decaying urban wasteland in which great droves of people stand motionless in dirty clothes and ashen faces. They do not and cannot acknowledge her as they are, in their minds, locked within the animated and fantastical world. The animated world is overseen and maintained by a small group of technicians living and working in huge blimps that float in the choking skies. It’s clear that the real world is crumbling and more and more of these techies are either getting too old to continue or are ‘crossing over’ to the fantasy world to live out their final days in fabricated happiness. When reality is damaged beyond repair, or simply disappears forever, so will the fantasy. If nothing else, that should probably be the biggest lesson taken from The Congress.