The very best science fiction films look to the future to examine the concerns of the present, and those that remain meaningful even decades after their release are those whose questions press at the very heart of humanity. From Metropolis to 2001: A Space Odyssey and Ghost in the Shell to Blade Runner, science fiction films are defined less by archetypal narrative patterns than by their futuristic settings and enduring themes. Like those, 1997’s Gattaca poses questions that, at the end of the 20th century, were not only timely but have so far remained timeless. Surprisingly prescient and provocatively engineered, writer-director Andrew Niccol’s Gattaca remains a stylish, moody, neo-noir thriller that probes the conflicts between free will and determinism in a future where genetic engineering is not only possible but ubiquitous.

In Gattaca’s “not-too-distant” future, a genetic registry denotes those conceived naturally as “in-valids” more susceptible to predictable genetic conditions. Played by Ethan Hawke, Vincent Freeman (pay close attention to the script’s intentional uses of naming) is one such “faith baby” and predicted to live only to the age of 30.2. He dreams of traveling to space but as an “in-valid” must develop an elaborate cover scheme to pass as a “valid.” His struggle to overcome genetic discrimination to realize his dream of space travel drives the narrative. To realize his goal, Vincent scavenges from the now-paralyzed “valid” former athlete Jerome Eugene Morrow (Jude Law), using samples of his hair, skin, blood and urine to pass detection at Gattaca Aerospace Corporation, where an upcoming mission to Saturn’s moon Titan is planned. Vincent’s ruse is jeopardized by his own DNA, which he must constantly cleanse and conceal.

In the 1990s, widespread genetic engineering seemed possible, perhaps even imminent, in the wake of several decades’ worth of innovation following the formulation by Watson and Crick of the physical structure of DNA, a large chemical molecule strung together from different beads in a unique double helix structure. A second breakthrough came when Frederick Sanger established the means of finding specific genes within broader code, or gene sequencing. Once scientists understood what genes were, how they worked, and how they could be altered, the Human Genome Project began mapping human genomes, which paved the way for recombinant technologies used, for instance, to grow “bits” of pancreas or brain cells to help those injured or disabled. Or to clone beings, essentially making DNA from DNA. These advancements accelerated the kinds of ethical questions that had existed since Shelley’s Frankenstein and even back to the myth of Prometheus. If humans can control their own evolution, if they can modify or replicate their genetic code, who makes the decisions, and based on what criteria?

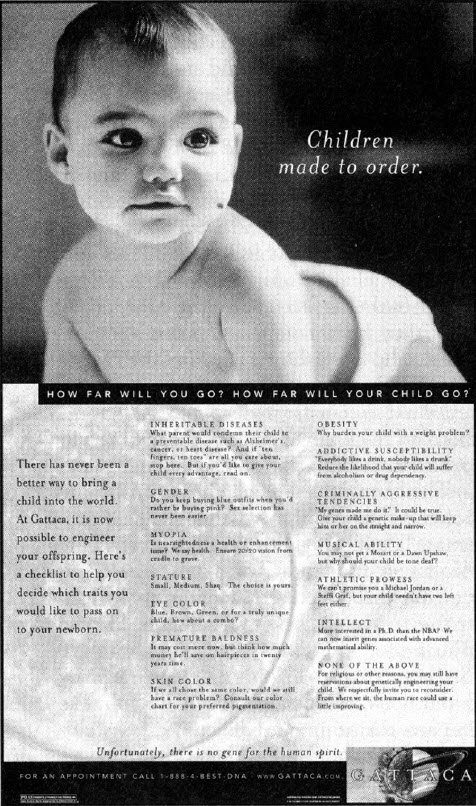

Gattaca’s scenario of a eugenics-determined future seemed especially pertinent back in 1997. Without mention of the film, its producers placed a mock ad in the Washington Post and other dailies, promoting a menu of genetic traits that could be selected for one’s child just as if ordering options on a hamburger, bicycle, or automobile. Among the selections: gender, stature, eye and skin color, musical ability, athletic prowess. Or one could reduce the risks for obesity, addictions, disease, or criminal behavior. “At Gattaca, it is now possible to engineer your offspring,” the ad promised. Swayed by the tagline’s promise of “children made to order,” within days over 50,000 potential customers reportedly responded.

That response suggests both, first, that in 1997 the ability to “design” a child was something those thousands of potential customers thought plausible and, second, that it was one they thought desirable. If for a mere fee one could virtually guarantee one’s child would not carry, say, a predisposition to mental illness, alcoholism, heart disease, or Alzheimer’s, who would not be tempted? The Gattaca ad did not speak to the ethical dimensions of genetic alteration, those that have vexed scientists, philosophers, and ethicists for decades. But it, like the film itself, spoke eloquently to just how enticing and problematic this particular type of eugenics would prove.

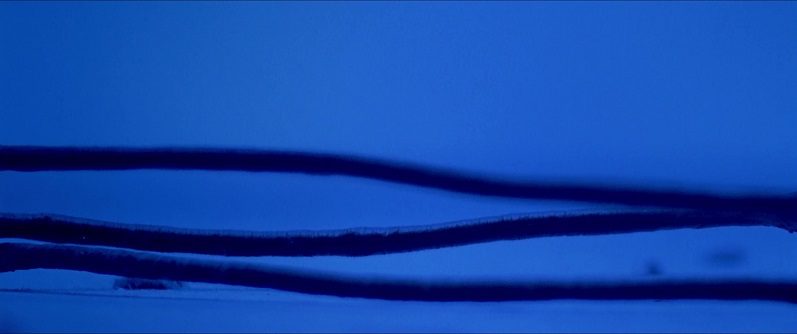

Aside from the broad-strokes eugenics-ethics debate its plot engendered, Gattaca from its first moments evokes a stylish, moody, postmodern neo-noir vibe. The opening credits sequence depicts the flotsam of samples—fingernails, hairs, skin shavings, the detritus of Vincent’s daily regimen, shot in extreme close-up and 320 fps slow motion, set to Michael Nyman’s magisterial score. Designer Michael Riley used oversize practical props like cable wires for hair and plastic sheeting for nails. The letters G, T, C and A highlighted in the opening sequence represent the four DNA bases (Guanine, Thymine, Cytosine, Adenine) and eventually combine to form the film’s title card. Other than those fonts, and prior to the digital filmmaking resolution, the sequence is shot entirely on film, just one instance of Gattaca’s visual inventiveness.

That credit sequence is just the introduction to a film whose visual design is both simple and ageless. Most sets are minimalist, evoking an uncluttered, hygienic, and stable mood that undercuts the film’s biopunk ethics. While the sets themselves are abstract and spartan enough to suggest a “not-too-distant” future, the color scheme and lighting are expressly neo-noir in their influences, imbuing Vincent’s obsessive behaviors and moral conflicts with shadow and chiaroscuro.

The props that sub for 21st-century inventions—fingerprint readers, digital ID cards, blood samplers—are all physical and lo-fi rather than digital and high-tech. On a broader scale, several sets employ spiral staircases that suggest the recombinant strands of DNA molecules themselves. With its languid pace (an average shot length of 6.7 seconds), slow reveals, and measured movement, Gattaca’s is a clean, suggestive, inspired look, its occasional despoilment with human blood, vomitus, and feces indicating just how messy messing with DNA can become.

What Gattaca, for all its stately, complex visual design and pacing, ultimately suggests, though, is not only a rejection of genetic engineering, specifically, but of science generally, in ways that will mirror our own ethical dilemmas today. As Vincent pursues his goal, his character is posited as the script’s rootable underdog, the “loser” in the genetic lottery that saddled him, as an “in-valid” of natural birth, to a propensity to multiple defects and projected expiration date that sets the narrative’s clock ticking. While Gattaca’s eugenics themes and visual design are innovative, its plot is pure underdog-hero-against-the-corrupt-system contrivance. A murder at Gattaca Corporation sets off an investigation that threatens to expose his secret existence while Vincent works feverishly to protect his ruse and achieve his goal.

Vincent Freeman and Jerome Eugene Morrow serve as foils to each other. Where Vincent is a faith baby whose faulty genetics predispose him to an array of “defects” and consign him to an early demise, those very same markers seem to have instilled in him a remarkably strong instinct for survival, a drive to disprove his predicted fate. If labeled an “in-valid” he can function only in the most menial of positions. Jerome, meanwhile, the designer baby poised for greatness by virtue of his genetic engineering, cannot cope with anything less than perfection: his disability is later revealed as the consequence of a suicide attempt following a second-place finish in competition.

In this way, though, Gattaca, for all its timeliness, takes on an anti-science stance. Vincent depends on DNA from Jerome. Jerome—whose middle name is Eugene, if you see what Niccol did there—is a far less fully realized character than Vincent and relegated largely to a plot convenience, a means of allowing the protagonist fulfillment of his quest. Law’s suave performance in this, his first American film, is winning, even if his character is posited as a loser, at least in the major swimming competition that came to define his life.

The presentation of a disabled character is even more troublesome than it was in the dozens of films in the era that employed physically able actors in disabled roles that often led to acclaim and awards, from My Left Foot and Forrest Gump to Million Dollar Baby, Rain Man, and Born on the Fourth of July. (How frequent? Between 1988 and 2015 a third of the Best Actor Oscars were awarded for abled actors playing characters with disabilities.) In Gattaca, Law’s paraplegic former swimmer character is little more than a mere foil, a means to a narrative end, and not only retrograde but one that ultimately betrays the film’s ethical convictions.

In essence, Gattaca is all about the trial and triumph of its protagonist, Vincent, the “free man” and his singular personal ambition. That to achieve it Vincent depends on the DNA of the paraplegic Jerome whose character commits suicide once his purpose—granting Vincent physical evidence of genetic superiority—suggests that the film is largely invested in Vincent’s individual quest and not the broader questions about genetic engineering. Vincent earns his flight to Titan through the assistance of Jerome and others, including Dr. Lamar (Xander Berkeley), who oversees the corporation’s rigorous DNA testing. But Vincent’s goal is no longer to subvert an unjust system, and those who suffer under its hierarchies are quickly forgotten. His is instead a nearly monomaniacal quest of mythical rugged frontier individualism.

On the surface, Gattaca seems to suggest that a distrust of science is healthy, that technological progress ought benefit all of humankind. But Vincent’s quest leaves behind those, like Jerome, who also suffer unduly under a hierarchical regime. As the protagonist Vincent does nothing to benefit or even honor those who made his achievement possible. If the film hopes to suggest that genetic engineering mismeasures humanity, its narrative ultimately leaves the eugenicist dystopia Vincent transcends fully intact. The protagonist may have escaped Earth for someplace new, but the problems inherent in genetic engineering remain. No one benefits from Vincent’s triumph other than Vincent himself.

It’s interesting, of course, to reconsider Gattaca in light of contemporary response to the coronavirus pandemic. Like Vincent, many have adopted an “all-about-me” approach, willing to risk or abuse others to achieve personal gain. Others turn a blind eye to the plight of those less fortunate. Vincent felt the system that was designed to ensure genetic conformity was rigged against him, and because it conflicted with his own personal ambitions, it was unjust. Today many use that exact same line of reasoning in defense of their vaccine hesitancy or anti-mask rhetoric. But it’s no less persuasive in our current pandemic than it was in the “not-too-distant” future Gattaca depicted in 1997. Vincent may have achieved his dream, but he left behind an unjust world of eugenic discrimination. Any one of us today may enjoy a personal freedom to go unmasked or unvaccinated, yet doing so surely endangers others.

At the time and again today, Gattaca’s concerns were—and are—real indeed. Gattaca was conceived at a time when gene editing had just become possible, and within a few decades significant advancements were made in its accuracy and efficacy. By 2015, the CRISPR technology had been used to edit the DNA of human embryos to prevent beta thalassemia, in very nearly the exact kind of scenario Gattaca depicted. And that advertisement for the fictional baby-designing company? By 2019, one company offered prospective parents the option of selecting the most palatable options from a set of in-vitro fertilized embryos. Meanwhile some anti-vaxxers today claim that coronavirus vaccines, with their mRNA technologies, carry microchips used for purposes of surveillance (they don’t)—another condition to which Gattaca alludes, with its frequent use of imagery and technology designed to locate, identify, and demarcate DNA.

Gattaca was voted in 2011 by NASA scientists the “most plausible” of science fiction films, and time has proved it so. Its casting, design, editing, and style lend to its innovative narrative conceit a panache that makes it among the best science fiction films of its era. Yet for all its forward thinking, Gattaca can’t quite present a truly progressive narrative: its protagonist can act only in his own self-interest for his own selfish reasons, and those less fortunate find themselves either dead in his wake or consigned to toil in their genetically determined dystopia. (Gattaca may also be as blindingly white a film as any you have seen; alongside its supporting cast of Uma Thurman, Alan Arkin, Gore Vidal, and Ernest Borgnine, Blair Underwood played the geneticist who, in flashback, advised Vincent’s parents on their designer options.) Meanwhile, Vincent achieves his dream of leaving Earth behind for a better place.

Today, as multibillionaires concoct their schemes for intergalactic travel on the backs of their underpaid laborers, as disabled communities strive for rights and recognition, as society finds itself isolating one group from another by virtue of vaccination (itself a mutation of a spike protein in our mRNA if not our DNA), Gattaca, like the best science fiction films, remains relevant in the most troublesome of ways. Any of us might hope to strive to create a better self from the DNA we inherit, to exercise our personal liberties, or to achieve our goals. But in the end, those individual quests and ambitions must always be measured against their costs. In Gattaca, Vincent achieves his dream, but the world he leaves behind remains an ableist dystopia.