What IF…?

What if…? is more than a new Marvel series. It’s the question that underpins so much great science fiction. What if the hierarchies of biological evolution were upended? What if artificial intelligences rebelled? What if humans colonized new worlds or mastered time travel? And what if—in the case of John Frankenheimer’s 1966 brilliant body-horror science-fiction paranoiac thriller Seconds—any of us could have a second shot at life, a new body, face, identity?

Seconds is hardly the only science fiction film to ask that particular what-if question. Indeed, the trope is a familiar one. But Frankenheimer’s film, considered a colossal failure upon its initial release, addresses the question with a surrealistic visual panache and surprisingly uncanny insight. Featuring Rock Hudson in perhaps a career-best role as a titular “second,” Seconds’ dystopian look at aging and identity has well earned its contemporary cult-favorite status and, if you will, something of its own second life.

Science fiction filmmaking had yet to come into its own in 1966. Notwithstanding a handful of great films of the earlier classical age (Metropolis, Things to Come, Frankenstein and its progeny), science fiction was scarcely considered an important genre at all. The 1950s offered a heyday of films that offered thoughtful conceits but typically uninspired visual designs due to economic constraints and technological limitations. Then, the genre seemed to attract more of the Ed Woods of the cinema than the Orson Welleses, and nearly no major star of the decade featured in its films.

In fact, only in the 1960s did the Nouvelle Vague begin to upend existing hierarchies of film genres to the point where even an auteur like Jean-Luc Godard was as invested in science fiction as, say, literary adaptation or action thriller. Seconds can thus be seen as something of a transitional film in the genre. Before the highbrow high-tech of 2001: A Space Odyssey or the big-budget franchise sagas of Planet of the Apes or Star Wars, Seconds suggested that a heady director like Frankenheimer could use the genre to explore his own auteurist themes—in this case the paranoia and ennui of the middle-class bourgeoisie.

Frankenheimer’s earlier The Manchurian Candidate (1962) placed a brainwashed assassin at the center of a communist conspiracy to overthrow the U.S. government. His Seven Days in May (1964) also concerned a military-political takeover, this time in the context of disarmament negotiations. Seconds, adapted from a 1962 John Lewis Carlino novel by David Ely and said to serve as the third film in a loose trilogy of Frankenheimer’s “paranoia” films, follows in a similar vein, especially in terms of its thoughtfully literate and cinematically astute approach to the content. Where those earlier films both addressed international intrigue and espionage, Seconds is by far a more intimate affair, the story of a single middle-aged man’s attempt to buy himself a “second” lease on life.

Seconds’ narrative twists and turns. The protagonist, Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph), unloved by his family and unfulfilled by his career, finds himself contacted by a ghost of sorts, an old friend thought dead whose instructions deliver to him a mysterious address. Frankenheimer takes Hamilton through a noir-like labyrinth of clues and detours, where at each step his perspective is clouded, his senses undermined by the shifting, unstable settings. With his cinematographer, the brilliant deep-focus pioneer James Wong Howe, Frankenheimer invests each of these early scenarios with a visual panache, disorienting Hamilton—and us—to set the stage for the big-stakes decision that will follow.

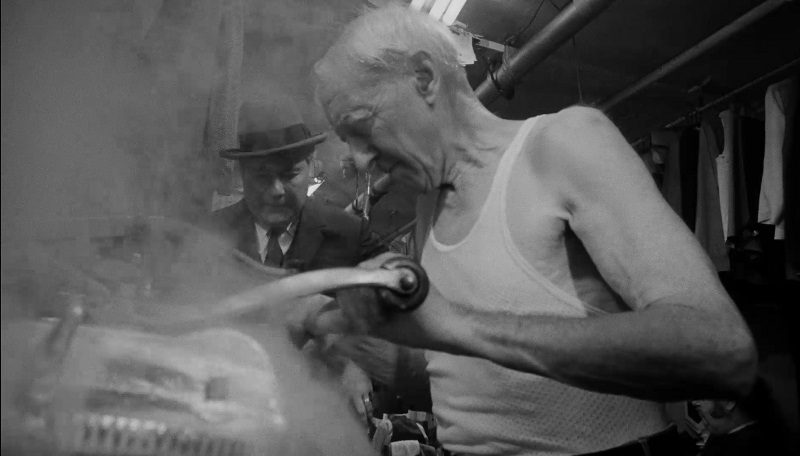

The opening credits, designed by Saul Bass, stretch and distort human anatomy—eyes, nose, mouth, teeth—to unsettling proportions and in ways that predict the film’s second act. The first sequence of Hamilton fighting the mass-transit crowds at Grand Central Station use Howe’s famed wide-angle lens and deep focus with an oddly gliding over-the-shoulder camera movement that is simultaneously lyrical and creepy. Detours on the circuitous route to his unknown destination are shot with similar energy, first in a laundry filmed with chiaroscuro clouds of steam and then in a meat market where hundreds of cow carcasses form a foreboding maze. Each disorienting step in the puzzle of Seconds’ plot triggers another level of visual anxiety.

Once Hamilton arrives at his destination and before the offer is revealed, Arthur stumbles upon a room where dozens of men sit quietly reading and watching portable televisions at rows of spartan desks. It’s a disquieting scene that can feel superfluous at the moment but will gain greater importance towards the end of the film. Back in the waiting room, he is slipped a drug in his coffee and shown sexually assaulting a woman. Though hesitant, and in part because of the potential for blackmail, he ultimately accepts “The Company’s” offer: an elaborately staged death by hotel fire, followed by extensive plastic surgery, physical therapy, training, relocation, and, in sum, a brand-new identity and life.

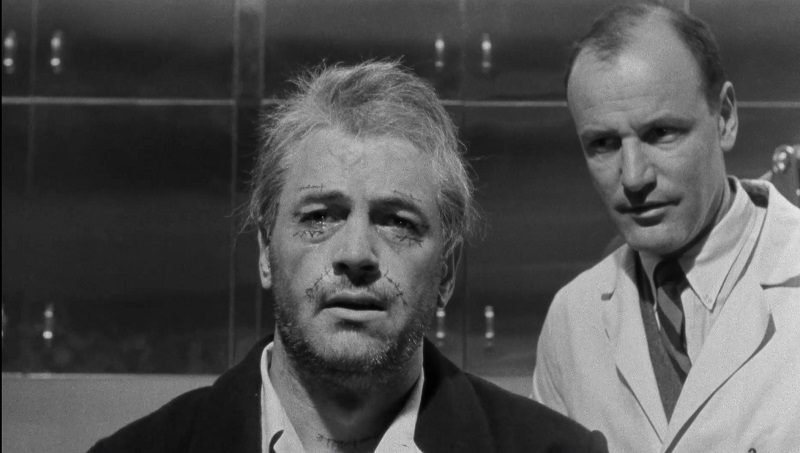

The subsequent surgery scenes too are brilliant set pieces by Frankenheimer and Howe. Frankenheimer recalls in his director’s commentary how he gained access to shoot an actual rhinoplasty as Hamilton undergoes plastic surgery. Those close-ups proved a bit much for one camera operator who Frankenheimer claims fainted at the sight! But the end result is persuasive as the injections, incisions, and sutures eventually yield the desired result: Arthur Hamilton is made to look brand new, his second life underway, and to his surprise, just like … Rock Hudson.

Here is where Seconds’ casting of Hudson as the remade Hamilton with a new name—Antiochus (“Tony”) Wilson—and identity is genius. Could any person understand better the desire to assume a new identity than Rock Hudson himself; born Roy Harold Scherer Jr. in Winnetka, Illinois, soon abandoned by his birth father and adopted without consent by the despised officer who married his mother and changed young Roy’s last name to his own? After a stint in the Navy, Scherer moved to Los Angeles to live with his biological father before connecting with agent Henry Willson, who literally gave Roy his new name and worked to shape his image for Hollywood.

By the 1950s, Hudson had become among the biggest of box-office stars. His major successes were, at first, melodramas where he played a nearly unattainable masculine romantic ideal in films like Magnificent Obsession, Giant, and All that Heaven Allows, followed by his largely neutered romantic comedies co-starring the suddenly-sexy Doris Day. Though he received no awards and little acclaim for his performances, audiences largely adored his affably vigorous, chivalrous, and honorable characters. Only Hollywood insiders knew his secrets. His marriage to Willson’s secretary Phyllis Gates was little more than a publicity sham and the cinema’s icon of heterosexual romance was in private life a gay man forced by his industry to live a public lie in constant fear of outing or blackmail. Rock Hudson was if anyone, indeed, a “second.”

However well suited the movie star version of Rock Hudson was to the narrative of Seconds, however, his casting was probably also responsible for the film’s poor initial reception. The film premiered at Cannes to a chorus of boos. Paramount had to cut several minutes of nudity. Middling reviews led to poor box office. Hudson, though game, was playing against type as an unlikable fiction, a Frankenstein’s-monster-made-Faustian-bargain, not even the film’s protagonist, or even a “real” character in the film’s diegesis.

At the time of Seconds’ release, again, science fiction had yet to really trigger the public imagination as an intellectual genre. Those few aficionados of sci-fi eager for the kind of provocative narrative Seconds offered had little interest in a film where an aging matinee idol was top-billed, and those fans of Hudson’s earned from his arch melodramas and Doris Day rom-coms had little interest in a paranoiac sci-fi thriller with Hudson as a graying, unlikable, and ultimately unreal character.

Today, however, cinephiles know well Hudson’s full story, from his Midwestern origins to early days in Hollywood, from his box-office popularity and longstanding passing to his later death from AIDS. And that knowledge, paired with a greater interest in and appreciation for those 1950s melodramas and comedies based on the layered, complex readings of queer studies and psychoanalysis, lends Seconds much of its vitality. Hudson himself was, at the time Seconds was made, a man who faced significant doubt about his career accomplishments, whose youthful vigor had begun to wane, and who had passed in a guise known only to some and well hidden from others. His own life backstory made him especially well suited for the role of Antiochus Wilson, even if it was his physique and visage that Seconds posited as the ideal for which Arthur Hamilton would abandon his own.

Viewing Seconds today, a full 55 years of middle age beyond its 1966 release, makes for an intoxicating cocktail of scientific conceits and cinematic genres. The promise of renewal—that we are not indefinitely bound to our biological inheritance or happenstance—is not only the subject of genetic engineering and sequencing but even identity, as fluidity and change now underpin contemporary conceptualizations of selfhood. Our digital worlds offer us avatars and alter egos that can be as fulfilling or frustrating as our more corporeal existences. Tech moguls invest millions in foundations dedicated to longevity research.

In Seconds, a paying customer can be transformed into something, someone, entirely new, a customizable identity that will cure inherited or acclimated flaws, but the promise of this sci-fi premise soon becomes for Arthur-Hamilton-cum-Antiochus-Wilson a horrorshow. After Tony, as he calls himself, lets loose at a Dionysian bacchanal, the one that got the censors snipping, he descends quickly into drunkenness and self-pity. Can he go back to his former home, his widow, his prior identity?

The final of Seconds’ many brilliant surprises unfolds when Tony, desperately pleading with The Company for a second—technically now a third—identity, is consigned to a waiting room where he realizes what he had not earlier: that each of the others there is just like him, in a purgatory, hoping for a fresh assignment and a new identity. But to earn one he must proffer The Company a new mark, just as his supposedly dead friend did him. Arthur, it turns out, was himself just a mark, a means for his “friend” Charlie to a second life. But Arthur had no friends, or even enemies, and so he has served The Company its purpose. And, to his chagrin, outlived his usefulness. His only value now is his mortal shell, the physical corpse to be used to fake the death of the next “second.”

What if to assume a new identity cost us, as Arthur Hamilton assumes, only our money? What if we were not bound by our biology and circumstance? What if, just around the corner, the science existed for any of us to become an entirely a new person? Seconds’ approach to that eternal question may not have found much of an audience in the mid-1960s, when Hudson was known as an unambiguously straight matinee idol and science fiction was a low-budget, B-movie playground. And Seconds surely did not lead to a new identity for its star, who would retreat to the safety of benign television appearances for most of the the rest of his career. But Seconds today enjoys its second life as a classic sci-fi/body horror film, one in keeping with the tone of its director’s prior conspiratorial thrillers, and one that in retrospect, ever-so-perfectly cast an aging, closeted, risk-taking Rock Hudson as a man who was, in essence, an unsustainable fiction.